[D]on’t rip up old stories – Henry Fielding, Tom Jones

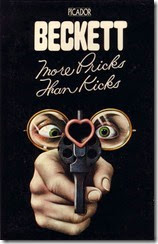

Tim Martin ends his one-star review of Echo’s Bones in The Telegraph by labelling it a work of interest to “specialists and masochists only”; I might add ‘completists’ but he does hit the nail squarely on the head. If you’ve never read Beckett before starting here will likely put you off for life. If you have read his more accessible stuff then read anything else—read everything else—before you approach this; it is not for the faint-hearted. ‘Echo’s Bones’ itself is a short story, a long short story admittedly—some 13,500 words (longer than some of the sporadic prose pieces Beckett produced at the end of his career)—which was intended to pad out (or may we should say ‘round out’) his short story collection then known as Draff but which was renamed More Pricks Than Kicks. A much catchier and less unpleasant title.

The collection had been accepted by Chatto & Windus in September 1933 but Charles Prentice had wondered whether Beckett had another story he could include since he felt the collection a little thin. Some have described More Pricks than Kicks as a novel-in-short-stories and that’s not an unreasonable description since all the stories bar the last one feature the first of his gentleman tramps, Belacqua Shuah. Technically he is in the last story—at least his corpse is—as he died under the surgeon’s knife in the penultimate story, ‘Yellow’. Not having anything to hand that would do—and having already cannibalised his first novel Dream of Fair to Middling Womenbelieving it unpublishable although it did finally see the light of day in 1992—Beckett decided to dash off something new and feeling that to try to cram in another would disturb the book’s flow—he might have called it its “involuntary unity”—he felt his only option was to tag on a “recessional story” at the end and to resurrect Belacqua—literarily—for this purpose. An inspired idea I have to say.

Beckett’s writing can be broken into distinct phases. His generally most accessible is his middle period from Watt, through Molloyand Malone Dies to the early plays like Waiting for Godot and Krapp’s Last Tape; his later theatre work (following his 1946 epiphany where he realised the way forward “was in impoverishment, in lack of knowledge and in taking away, in subtracting rather than adding”) is minimal often with no more than a single character on stage (although he was fond of disembodied voices as in Eh Joeand Footfalls) and the prose of this period is likewise short, frequently experimental employing unusual syntax and difficult to grasp; More Pricks than Kicks belongs to Beckett’s early period when he was very much in thrall to James Joyce and it shows although even at this stage he was well aware that he’d never make a go of it on his own if he didn’t “get over J.J.”. His writing from this period is difficult in another way entirely.

He apparently struggled with ‘Echo’s Bones’—on the first of November in a letter to his friend Thomas McGreevy as he was still known then (post-1943 he became Thomas MacGreevy) he said he was “having awful trouble with it” but this is typical of Beckett; he’s the most self-deprecatory writer you’ll even come across; nothing he wrote was good enough and he made out that writing was a painful experience for him—but by the tenth of that month Prentice had the manuscript in hand—“What a big one!” he responded. “I shall read it with delight this week-end…”—only to have it rejected promptly on the Monday:

He apparently struggled with ‘Echo’s Bones’—on the first of November in a letter to his friend Thomas McGreevy as he was still known then (post-1943 he became Thomas MacGreevy) he said he was “having awful trouble with it” but this is typical of Beckett; he’s the most self-deprecatory writer you’ll even come across; nothing he wrote was good enough and he made out that writing was a painful experience for him—but by the tenth of that month Prentice had the manuscript in hand—“What a big one!” he responded. “I shall read it with delight this week-end…”—only to have it rejected promptly on the Monday:

It is a nightmare. Just too horribly persuasive. It gives me the jim-jams … People will shudder and be puzzled and confused… I am certain that Echo's Bones would depress the sales very considerably ... the only plea for mercy I can make is that the icy touch of those revenant fingers was too much for me ... Please write kindly.

Beckett, ever kind (he was a very kind man), acquiesced without fuss—which does not mean he wasn’t hurt—and publication went ahead of the manuscript as submitted following some minor editing; material from ‘Echo’s Bones’ provided an improved ending to the short story ‘Draff’ so his efforts weren’t entirely in vain. On the sixth of December Beckett did, however, produce a poem called ‘Echo’s Bones’:

Echo's Bones

Asylum under my tread all this day

their muffled revels as the flesh falls

breaking without fear or favour wind

the gantelope of sense and nonsense run

taken by the maggots for what they are

which went on to become the title poem in his collection Echo's Bones and Other Precipitates, published in 1935; too good a title to waste. The short story itself was forgotten about and until now has only been available to scholars.

How to read ‘Echo’s Bones’? In an entertaining article in The New York Review of Books entitled ‘What to Make of Finnegans Wake?’ Michael Chabon valiantly tries to explain Joyce’s final novel. The book finally appeared in print in 1939 but it had taken him some seventeen years to get to that point. Chabon offers a number of answers to his question—all of which have a certain validity—but this one I’d like to highlight:

(e) Its author’s own super-cleverness, the daedalian prison in which Joyce starved his genius, having forgotten that, since a labyrinth is as hard to penetrate as to escape, most of Asterion’s intended meals must have failed to make it to the jaws and waiting belly at the labyrinth’s centre.

Swap ‘Beckett’ for ‘Joyce’ and you could say the same of ‘Echo’s Bones’ assuming you actually understand the above paragraph without having to google ‘daedalian’ and ‘Asterion’ (which I did and it didn’t help much). In a letter to McGreevy at the start of 1934 Beckett wrote:

I haven’t been doing anything. Charles’s fouting à la porte [kicking out] of Echo’s Bones, the last story into which I put all I knew and plenty that I was better still aware of, discouraged me profoundly […] But no doubt he was right.

Why is the story such a hard read? John Pilling has remarked that at times there are “so many echoes that they seem to multiply to infinity, and yet they are little more than the bare bones of material without any overarching purpose to animate”  and as Mark Nixon, director of the Beckett International Foundation, notes in his introduction:

and as Mark Nixon, director of the Beckett International Foundation, notes in his introduction:

[T]here is hardly a sentence in ‘Echo’s Bones’ that is not borrowed from one source or another, bearing out Beckett’s own statement that he had ‘put all I knew and plenty that I was better still aware of’ into the story. These references range from the recondite to the popular (Marlene Dietrich, French chansons), and are inscribed in the text both openly and covertly. […] [B]oth on a verbal and a structural level, it harnesses a range of materials, from science and philosophy to religion and literature. As its title suggests, this is a story made up of echoes, of allusions to multiple cultural contexts.

So what am I saying, that ‘Echo’s Bones’ is some kind of showpiece or cadenza? Possibly. Cadenzas are all well and good in small bursts but after a while—and usually not a very long while—we tire of the virtuosity, the clever fingers, and want to go back to something we can hum in the shower. There’s no doubt that ‘Echo’s Bones’ was written by a very clever, well-read man. It was also written by a twenty-six-year-old who’s just had his first book of fiction accepted—his essay-cum-manifesto Prousthad already been published—and maybe felt like showing off a bit. This is pure conjecture of course. Suffice to say what he produced veers from dazzling to blinding in a matter of a couple of paragraphs. We are eased though into the story in typically Beckettian fashion:

The dead die hard, trespassers on the beyond, they must take the place as they find it, the shafts and manholes back into the muck, till such time as the lord of the manor incurs through his long acquiescence a duty of care in respect of them. They are free among the dead by all means, then their troubles are over, their natural troubles. But the debt of nature, that scandalous post-obit on one’s own estate, can no more be discharged by the mere fact of kicking the bucket than descent can be made into the same stream twice. This is a true saying.

‘Echo’s Bones’ is forty-nine pages long. The annotations that follow it fill fifty-six pages. Most of these explain literary and biblical quotes and nods (in his reviewSeamus Deane calls ‘Echo’s Bones’ a “purée of references”) or highlight Beckett’s fondness for wordplay; there are many hidden meanings in this text. The problem for the contemporary reader—although I expect it would have been no less a problem for a reader back in the thirties who would not have had the benefits of such fastidious research—is that no one bar someone like Beckett will have even heard of most of these texts let alone read them, e.g. Garnier’s Onanisme seul et à deux or Chaucer’sThe Parliament of Foules. Of course you don’t always need to know where a reference hails from to make sense of the text—when Beckett talks about “the quick” (as opposed to the dead) most people will be well aware he means the living; some may even recognise the title (it’s been used by numerous authors and filmmakers) but few will realise that it originates from any of three passages in the King James Bible and they don’t need to know—but typically you do because Beckett is nothing if not a subtle writer and he expects you to pick up on the undertones or maybe overtones would be better since much of the language is highfalutin although not all; he can be base as well.

If you are familiar with any of Beckett’s later works every now and then you’ll trip over a line of a phrase that sounds familiar like the oxymoronic “womb-tomb” (in one place referred to as “the lush plush of the womby-tomby”) which evokes Pozzo’s speech in Act II of Waiting for Godot:

Pozzo: They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it's night once more.

Birth and death are often mixed up in Beckett’s writing. Beckett told Billie Whitelaw, when she asked him if May in Footfalls was dead, “Let’s just say you’re not all there.” The same is true of Belacqua: he casts no shadow, he cannot see his own reflection (no, he’s not a vampire), he can, however, eat and drink, smoke cigars (his pockets are apparently crammed full of them) and—although this was not something he was renowned for whilst still alive he being that indolent—copulate. We first encounter Belacqua following his apparent resurrection (although whether his earthly remains have been disinterred is another matter) sitting on a fence “picking his nose between cigars, suffering greatly from exposure.” We learn that he has returned (been returned?) to take part in “three scenes … [a] little triptych” that form the material for this “fagpiece.”

Birth and death are often mixed up in Beckett’s writing. Beckett told Billie Whitelaw, when she asked him if May in Footfalls was dead, “Let’s just say you’re not all there.” The same is true of Belacqua: he casts no shadow, he cannot see his own reflection (no, he’s not a vampire), he can, however, eat and drink, smoke cigars (his pockets are apparently crammed full of them) and—although this was not something he was renowned for whilst still alive he being that indolent—copulate. We first encounter Belacqua following his apparent resurrection (although whether his earthly remains have been disinterred is another matter) sitting on a fence “picking his nose between cigars, suffering greatly from exposure.” We learn that he has returned (been returned?) to take part in “three scenes … [a] little triptych” that form the material for this “fagpiece.”

He has been enjoying, since his resurrection, “a beatitude of sloth that was infinitely smoother than oil and softer than pumpkins” in the “womb-tomb,”—he was after all named after the lazy man Dante encounters on the shores of Purgatory (PurgatorioCanto IV:88-139) and as Shuah was the mother of Onan we can only assume that in death as well as life he’s nothing more than an idle wanker—but has found his “soul begins to be idly goaded and racked, all the old pains and aches of my soul-junk return!” It seems as if the living world, rather than the afterlife, is where his torment is to take place (or at least begin), and he’s been brought back for “major discipline”. Belacqua, we discover, has been dead for forty days. The number forty in the bible is significant: in a few instances periods of judgment, testing or punishment last forty days (Nineveh, for example, was given forty days to repent, Jesus fasted in the wilderness for forty days and the flood waters didn’t disperse until after forty days).

His first encounter is with Miss Zabrovina Privet who bursts onto the scene, literally shooting out of a hedge. She recognises him as Belacqua “whom we took for dead, or I’m a Dutchman” but isn’t remotely fazed by his return:

“How long do you expect to be with us?” said Zabbrovina.

“As long as I lived” said Belacqua, “on and off, I have the feeling.”

“You mean with intermissions?” she said.

“Do you know” said Belacqua, “I like the way you speak very much.”

“The way I speak” she said.

“I find your voice” he said “something more than a roaring-meg against melancholy. I find it a covered waggon to me that I am weary on the way, I do indeed.”

“So musical” she said, “I would never have thought it.”

The book is full of witty banter; the same kind we’ve grown accustomed to in Waiting for Godot, Endgame and some of the less well-known plays. Why exactly it’s funny isn’t always obvious though. Take Zabrovina’s name: her forename has Russian roots (‘zabornyj’ – ‘indecent, course’; ‘zabornaja literatura’ is ‘literature of the fence’, or pornography’); privets (which also echo the Russian informal greeting ‘pryvet’) often are used to form hedges so Zabrovina is a hedge-rambler which I suppose is the rural Irish equivalent of a street walker. Within a few pages her true nature has revealed itself and she’s pinned him to the fence turning, metaphorically at least although who’s to say bearing mind much of what follows, into a Gorgon: “She tossed back the hissing vipers of her hair, her entire body coquetted and writhed like a rope, framed into a bawdy akimbo…”

Having had her way with him—if he’s been sent back to face a number of heroic tests he’s not exactly being stretched—she takes him back to her lodgings where she serves him garlic and white wine before, if I’m reading this right, having her way with him numerous more times:

…countless as it were eructations [belches] into the Bayswater of Elysium, brash after brash of atonement for the wet impudence of an earthly state – the idea being of course that his heart, not his soul but his heart, drained and dried in this racking guttatim [drop by drop], should qualify at last as a plenum [a space or all space every part of which is full of matter] of fire for bliss immovable…

Suddenly he finds himself perched “on the lofty boundary of a simply enormous estate, guzzling a cheroot” shedding a tear for his “besotted soul (his misnomer)” when he’s hit from behind—a blow to “his eminent coccyx”—by a golfball recently struck by its owner and the owner of the estate itself, the giant Lord Haemo Gall of Wormwood, who wears a tasselled red tarboosh (that would be a fez to you and I):

“Whoever you are” he cried, “Jetzer or Juniperus —”

No answer.

“Firk away” he screamed, “firk away. It is better than secret love.”

“Love” said a wearish voice behind him, “turn round my young friend, face this way do, and tell me what you know of this disorder.”

Lord Gall it turns out is sterile and numerous not-especially-subtle-or-clever asides about golf sticks and golfballs ensue. Gall invites him to his home where he lays his cards on the table: Lady Gall must produce a son and heir to ensure that Wormwood does not fall into the hands of Baron Extravas. This conversation doesn’t take place in the comfort of his castle but rather up a tree where Lord Gall shoves Belacqua; they spend the afternoon drinking in an aerie. Belacqua is asked if he can rise to the challenge although who can tell why his lordship would demand this of a man he’s only just met. Suffice to say, after some verbal parrying, Belacqua acquiesces. An ostrich called Strauss appears and the two men ride on in to the castle where Belacqua does his bit and Moll Gall turns up trumps:

Lord Gall was downstairs at the time, counting his golfballs. His medical advisers filed in. It was a dramatic moment.

“May it please your lordship” said the foreman, “it is essentially a girl.”

So it goes in the world.

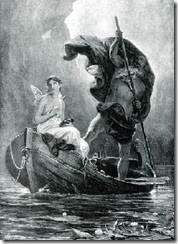

The final third (and most readable part) of this tale takes place at Belacqua’s graveside. As he’s sitting there “on his own headstone, drumming his feet irritably against the R.I.P.” he sees “a submarine of souls” out at sea and a familiar face (if you’ve read More Pricks than Kicks), the Alba. We are, of course, here supposed to make the connection with Charon’s ferry across the rivers Styx and Acheron although he might’ve been thinking about the Easter Rising of 1916. Meanwhile the groundsman from ‘Draff’ arrives “fortified with alcohol” intent on robbing Belacqua’s grave. In the earlier story he’d never been named but here we learn he’s called Mick Doyle. He appears to recognise the man perched on the grave but isn’t put off when Belacqua announces, “Fool! I am the body.”

The final third (and most readable part) of this tale takes place at Belacqua’s graveside. As he’s sitting there “on his own headstone, drumming his feet irritably against the R.I.P.” he sees “a submarine of souls” out at sea and a familiar face (if you’ve read More Pricks than Kicks), the Alba. We are, of course, here supposed to make the connection with Charon’s ferry across the rivers Styx and Acheron although he might’ve been thinking about the Easter Rising of 1916. Meanwhile the groundsman from ‘Draff’ arrives “fortified with alcohol” intent on robbing Belacqua’s grave. In the earlier story he’d never been named but here we learn he’s called Mick Doyle. He appears to recognise the man perched on the grave but isn’t put off when Belacqua announces, “Fool! I am the body.”

Doyle threw down the mattock and took up the spade.

“There is a natural body” he said “and there is a spiritual one.”

[…]

“I’ll lay you six to four” said Belacqua “that you find nothing.”

According to the book’s annotations six to four were the odds placed on Hamlet’s swordsmanship although if you want a good example of how scholars can take a piece of text to pieces and then grind those pieces to dust see this article from The Oxfordian. I can just imagine the amount of fun Nixon and his team had trying to fit all the pieces together here but the danger in treating a text—as so often happens with a poem—as something to be solved and not read is that it ends up becoming even more unreadable than it started out being. Like all writers should, Beckett wrote what he wanted to read; he wrote out of his own experience and interests which were, let’s be frank, not to everyone’s tastes. He was an academic at heart and really has to be studied before he can be read. Think of ‘Echo’s Bones’ as the literary equivalent of Schoenberg’s early twelve-tonal works: it takes a while before you can hear the music.

The story’s title derives from an episode in Ovid'sMetamorphoses. I’m sure in my childhood I read the story of Echo—thanks to Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopaedia I actually had quite a decent classical education—but I still had to look it up to write this essay. In brief:

Echo was a beautiful nymph, a favourite of Diana, and attended her in the chase. But she had one failing; she was fond of talking, and whether in chat or argument, would have the last word.

One day Juno was seeking her husband, who, she had reason to fear, was amusing himself among the nymphs. Echo by her talk contrived to detain the goddess till the nymphs made their escape. When Juno discovered it, she passed sentence upon Echo in these words: “You shall forfeit the use of that tongue with which you have cheated me, except for that one purpose you are so fond of—reply. You shall still have the last word, but no power to speak first.”

From that time forth she lived in caves and among mountain cliffs. Her form faded with grief, till at last all her flesh shrank away. Her bones were changed into rocks and there was nothing left of her but her voice. With that she is still ready to reply to anyone who calls her, and keeps up her old habit of having the last word.

The Echo myth is one that continued to fascinate Beckett throughout his life and disembodied voices as I’ve already mentioned find their way more and more into his late plays and it was no great surprise to learn what Doyle finds in Belacqua’s coffin although in terms of the collection in which it was to be a part it does raise some questions assuming any of ‘Echo’s Bones’ is to be taken literally because this is Beckett at his most fabulistic, not a term one generally associates with him; ‘Echo’s Bones’ is essentially a fairy tale. But what delights is when you find the odd line that reminds you of the stuff he would produce later on, lines like:

After a long silence, suffered by Doyle as scarcely less than a tribute to his high-class folly, something inside Belacqua said for him:

“Sometimes he feels as though this old wound of his life had no intention of healing.”

“That sounds bad” said Doyle, “I grant you. Has he tried saline?”

“He has tried everything” said the voice “from fresh air and early hours to irony and great art.”

More Pricks than Kicks did not sell well. Fewer than 500 copies purchased in the first four months—better than Krapp’s seventeen—but only twenty-one copies in the six months after that and some twenty-five in the following three years. It was placed on the Register of Prohibited Publications in Ireland which can’t have helped and even library copies were removed. The remaining quires were pulped in two batches in 1938 and 1939 and the author even ‘mislaid’ his own copy. Chatto lost around a third of their outlay and Beckett’s royalties never totalled more than half of his £25 advance. Ever critical of his own work he came to regard these stories—including, of course, ‘Echo’s Bones’—as nothing more than juvenilia and was reluctant once he’d achieved a level of fame in later years to see the collection come back into print. One can only imagine what he would think about this latest edition despite the love and attention spent getting it ready. In that respect I have nothing but praise for the team involved; it is a lovely book.

More Pricks than Kicks did not sell well. Fewer than 500 copies purchased in the first four months—better than Krapp’s seventeen—but only twenty-one copies in the six months after that and some twenty-five in the following three years. It was placed on the Register of Prohibited Publications in Ireland which can’t have helped and even library copies were removed. The remaining quires were pulped in two batches in 1938 and 1939 and the author even ‘mislaid’ his own copy. Chatto lost around a third of their outlay and Beckett’s royalties never totalled more than half of his £25 advance. Ever critical of his own work he came to regard these stories—including, of course, ‘Echo’s Bones’—as nothing more than juvenilia and was reluctant once he’d achieved a level of fame in later years to see the collection come back into print. One can only imagine what he would think about this latest edition despite the love and attention spent getting it ready. In that respect I have nothing but praise for the team involved; it is a lovely book.

One particular review of More Pricks than Kicks jumps out. It was by Edwin Muir for The Listener who wrote:

The incidents themselves do not matter much. The point of the story is in the style of presentation, which is witty, extravagant, and excessive. Mr. Beckett makes a great deal of everything; that is his art. Sometimes it degenerates into excellent blarney, but at its best it has an ingenuity and freedom of movement which is purely delightful.

Trust a poet to get him! Had he read ‘Echo’s Bones’ I’ve no doubt he would have extended this comment to encompass it. Tim Martin’s one star is too harsh, far too harsh. As Julie Campbell notes in ‘“Echo’s Bones” and Beckett’s Disembodied Voices’:

Many elements of ‘Echo’s Bones’, however, are shared with Beckett’s later writings: the strong focus on death and the afterlife; the lament of having been born; the oxymoronic “womb-tomb”…; the torments of living and the simultaneous desire for and dread of non-existence. Belacqua inhabits the story in an “in-between” space, dead but within the living world, recalling those interstitial spaces, where characters are somehow in between life and death that haunt Beckett’s work.

[…]

The fact that this story did not get published does mean that the very special quality of its humour and strangeness has been shut out of the Beckett canon.

Well now it has been. I still stand by what I wrote in the opening paragraph of this review. If you’ve read next to nothing by Beckett there’s plenty of other stuff you should check out before this unless you’re a particular aficionado of Joyce’s late work. As far as the prose goes I’d probably start with Murphy and the novella First Love. Don’t be tempted by the late prose simply because it’s short. Watch the plays first. They’re the best way into Beckett. But if in the weeks to come you do chance upon a cheap copy of Echo’s Bones it’s certainly not a waste of money. Stick on a shelf and maybe get round to it someday when the time feels right. You might be surprised.

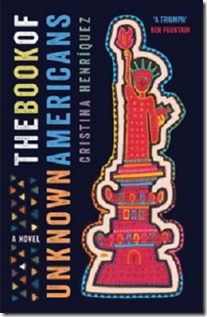

Cristina Henríquez’s

Cristina Henríquez’s

![Mavis Shoe[4] Mavis Shoe[4]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-z8TWnrZN3gU/U7PwF0R8XTI/AAAAAAAAIks/pWiJ47izvLE/Mavis%252520Shoe%25255B4%25255D_thumb%25255B1%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

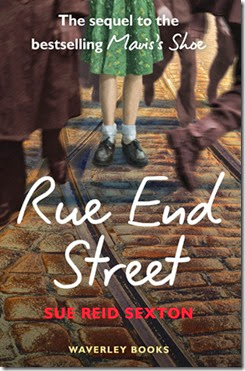

Sue Reid Sexton

Sue Reid Sexton

Marlen Haushofer

Marlen Haushofer

Dave Eggers

Dave Eggers

John Manderino

John Manderino