![Bed of Coals Bed of Coals]()

My wife, happening upon my journal, said:

“Writers are crueller than normal people.”

—Joseph Hutchison, ‘March 10: “From an Unmailed Letter”’

W.S. Merwin opens his 1968 essay, ‘On Open Form’ with the following statement:

What is called its form may simply be that part of the poem that has directly to do with time: the time of the poem, the time in which it was written, and the sense of recurrence in which the unique moment of vision is set.

Reading that essay prompted Joseph Hutchison to write his own, ‘Aspects of Time in Poetry’ in which he draws a distinction between three kinds of time: empirical time, subjective time, and duration. It’s a thought-provoking article. Time, of course, is linear. Our perception of it may not always be accurate but tempis fugits on regardless. Memory handles time in its own perverse ways. As Joe puts it in ‘This Day’:

All

that time scatters, memory gathers up—

keepsakes, relics, talismans.

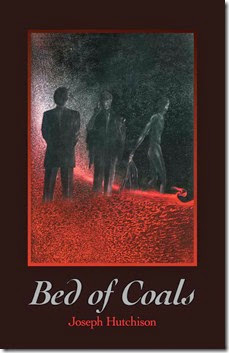

This is what makes his 1995 collection Bed of Coals (which has just been brought back into print by FutureCycle Press) such an interesting—by ‘interesting’ I mean ‘challenging’—read.

Unlike many poetry collections Bed of Coals has a storyline. It’s a multi-layered, discontiguous and spare one and one I struggled with at first; sadly—and masculinely—I’m a terribly linear person. In an author’s note at the start of the book Joe tries to explain the book’s structure:

Two different voices tell the following story. One belongs to an anonymous narrator, whose poems include my main character’s name—Vander Meer—in their titles. The second voice is Vander Meer’s own, and it surfaces in poems drawn from his “blue notebook” and in others written at a later date; the titles of these works are set in italics to differentiate them from the narrator’s. Vander Meer’s “blue notebook” entries, dated from March 22 of one year to March 21 of the next, are presented in the order Vander Meer himself chooses to read them. Readers who prefer plot to character are free to reconstruct the progress of Vander Meer’s crisis by reading the “blue notebook” poems in chronological order.

On reading through the collection I wondered about the third set of poems though—I couldn’t quite see how they fitted into the sequence—and so asked Joe to clarify how these were to be interpreted:

The other poems written by Vander Meer are—so my conceit goes—written as he contemplates the blue notebook poems. He is in dialogue with them, and with the person he was when in that downward spiral. These poems flesh out more of his story.

So, to clarify, we have Vander Meer’s story narrated from the outside (what I’m going to call ‘the objective poems’), his own thoughts as he’s immersed in the events recorded in a blue notebook (the subjective poems) and a third set where he looks back from having survived said events (the reflective poems); at least that’s my reading of them. I’ve no issues with any author providing instructions on how to read his or her book—perhaps more should—but once we have them we’re on our own for better or worse. This multi-layered approach is certainly different but it does screw with your general perception of time since the poems aren’t presented chronologically in terms of the events they describe or chronologically as they were written. I tried to work my way through the collection sequentially but lost the thread and so decided to read the poems in three blocks since I couldn’t work out how the objective and subjective timelines crossed.

As I was describing this organisation to my wife she reminded me of Doris Lessing’sThe Golden Notebook and its structure. From the novel’s blurb:

Divorced with a young child, and fearful of going mad, Anna records her experiences in four coloured notebooks: black for her writing life, red for political views, yellow for emotions, blue for everyday events. But it is a fifth notebook—the golden notebook—that finally pulls these wayward strands of her life together.

Lessing in the book’s preface claimed that the most important theme in the novel is fragmentation; the mental breakdown that Anna suffers, perhaps from the compartmentalization of her life reflected in the division of the four notebooks, but also reflecting the fragmentation of society.

![Razzle - John Ransom Razzle - John Ransom]()

The objective poems

There are thirteen poems in this group and although undated they appear to be presented in chronological order.

This isn’t prose and so we have to get by on scraps of biographical information and attempt to build up a picture. Vander Meer is a copy editor who aspires to be “an auteur”. As a child he struggled learning how to swim but did manage to learn how to float. It’s a strong and simple metaphor for a man whose life is going nowhere. He doesn’t even drive himself to work at this point; he gets the bus and when he gets off he struggles through the masses in much the same way he struggled through the water when trying to do the breast stroke. This is where we meet him in the opening poem of Bed of Coals musing to himself, “every skill /becomes second nature.” I suppose there’s some truth to that. They say you never forget how to ride a bike but when I swim nowadays I have to think about it; I’m not a natural swimmer and I, too, like Vander Meer, nurse some painful memories of learning to swim which I never did until I was about twelve and I only ever mastered the breast stroke.

Vander Meer’s colleagues say he’s not himself.

His clear, blue sky prose is all fog lately:

“Couldn’t sell steaks to a starving man!”

[from ‘VANDER MEER’S WEARINESS’]

We’re into the second poem now. He’s distracted; his mind’s not on the job. Perhaps a leave of absence would help although we’re still none the wiser regarding what’s up with him. The third poem takes us into one of his dreams; dreams, mostly bad, form a major part of this collection (twenty-six poems if I counted right). He knows he’s dreaming because he’s found himself replacing Cary Grant in North by Northwest. This poem does set the time frame because when he wakes he finds there’s “a second-rate actor / in the White House” which means we’re talking the eighties. (Ronald Reagan was in office from January 20, 1981 – January 20, 1989.) The eighties was the Me! Me! Me! generation. It saw the rise of the yuppie. Binge buying and credit became a way of life. Labels were everything. Tom Wolfe dubbed the baby-boomers as the ‘splurge generation.’ It was a bad time to be seen as anything other than successful.

This dream itself is not as significant as the one we hear about in the next poem ‘VANDER MEER IN TRANSIT’ in which, on the bus again, he overhears a couple talking:

“I took a night course on dreaming,”

she said. “If you dream it once,

it’s not prophetic. It’s just working out

anxieties....”

“And what if you dream

the dream more than once?”

“Then,”

she nodded, “it’s time to pay attention.”

This reminds him of a recurring dream in which his genitals are ripped off in the shower, a dream he first had “two years before his marriage failed.” He decides to call in sick.

In the next poem ‘ORPHIC VANDER MEER’ Vander Meer’s back in bed dreaming. This time it’s about having sex with someone whose marriage is collapsing. And also her faith it seems. Who is this person? Clearly not his wife.

In ‘VANDER MEER’S REVISION’ we’re at the halfway point, August—the sequence runs from March to March remember—and he’s alone during a heat wave. It’s a year on from when his wife told him:

“You want her? Your little bitch? Go

to her! Go to your bitch!”

And yet it’s not as simple as that:

So he left,

not explaining he was leaving for no one.

How could he speak that unreasonable truth?

What’s going on here? He’s cheated on his wife but he’s not leaving her for this other woman? It also suggests that it took a year for their marriage to get to this point, that it failed a full year earlier but something—momentum? habit?—kept things running.

In ‘VANDER MEER HOLDING ON’ he now has a car, a “new / used Ford” and is sitting outside what used to be the family home watching his daughter on her swing, the growing distance between him and his family symbolised by the last two line of the final stanza:

But his daughter, sailing higher, shrieks

with joy...and he grips the wheel—

white-knuckled Vander Meer! Shutting his eyes,

hearing his wife laugh and call, “Hold on!

Honey, hold on tight!” Her every push

pushing him farther out....

Notice the pun? Pushing father out? This distance is tackled again in the next poem, ‘VANDER MEER CRYING FOWL’:

Thus, her voice

on the phone—its hunger repressed

uneasily into choice etiquette: a proper

knife-and-fork tenderness.

Assuming this is his wife we’re talking about here. I’ll come back to this.

More dream imagery in ‘SAINT VANDER MEER AND THE DRAGON’:

Oh, he fears

sleep! For she comes to him in sleep.

“What I must do I will do,” she whispers.

Things are starting to get to Vander Meer in ‘VANDER MEER AT SUNDOWN’:

Thinks Vander Meer, All light’s

receding from me like the galaxies.

In ‘VANDER MEER AT SEA’ it’s still August. Which August though? A year after the break up? He happens on “a note / in her firm cursive,” directions he’s given her over the phone at some point. But who is the “her”? No, I think this is before the breakup of his marriage. I think this is him with the other woman and she’s the one breaking up with him. So maybe the voice on the phone a few poems back was his lover. Hard to be sure. In the bio on his blog Joe writes:

In the all the years of my writing life, I've responded to and aspired to a quality in poetry that I can only call "clarity." Not that I'm interested in clarity at the expense of honest complexity; I despise those bland accounts of near-death sailing "into the Light." Light is not always benign: it blinds as often as it offers revelation, as anyone who's grown up in my part of the world would know. That contradiction, if it is one (it could be that contradiction exists only in the mind), fascinates me continually.

Light’s a major theme in this collection. It feels like hardly a poem fails to mention it at least in passing: moonlight, “broken light”, “the grey TV light”, “shallow light”, daylight, “the effects of light”, “town lights”, lightning, twilight, “morning light”, “cloudlight”, “festive lights”, “windowlight”, “ripples of light”, “headlights”. It’s something I’ve noted in my own poetry, light as a metaphor for truth. I think it’s a good metaphor even if it is a bit obvious. Sometimes it’s very clear what’s going on with Vander Meer but at other times not as much; not every poem is equally illuminated. The problem is, by ‘clarity’ Joe doesn’t mean ‘transparency’. In an interview he expanded on the above:

[C]larity isn’t accessibility. (I’m not sure what accessibility means, because what’s accessible to one reader may not be accessible to another. So when we talk about accessibility, we’re getting into statistics: what percentage of readers understand this poem on first reading? On second? On third? Etc. It’s a useless term.) Clarity is also not an absence of ambiguity. Blake is notoriously ambiguous, but no poet writes with more clarity.

So—I’ve said what clarity isn’t but not what it is. I would say that my sense of clarity goes back to the medieval meaning of the word—“glory” or “divine splendour.” … Moments of clarity come through the senses but carry us beyond them.

So, perhaps rather than ‘clarity’ what he’s looking for in his poems—and therefore what we should be looking for—are insights, little epiphanies, flashes. Of course when Joe reads these poems he knows exactly what they’re about but as much as he’s trying to allow us inside his head he doesn’t always manage it. And, oddly enough, neither does the omniscient narrator. But here what’s going on seems reasonably clear:

“I can’t,” she said. It was simple—

like a blunt gaff to the chest. “I just

can’t.... Not right now. Not yet,”

she said. And he said he felt the same:

“It’s my kid,” he lied, thinking—

I am going to die....

In ‘VANDER MEER AT BOTTOM’ we can see him beginning to fall apart. For once he’s lying in bed and not dreaming:

Sunken like a river rock, Vander Meer reads

the ripples of light that passing cars

scrawl across his bedroom wall. No

breathing beside him...no child’s

next door.

Here’s probably as good a place as any to ask: Why Vander Meer? It’s an odd name. Why not Smith or Jones? In an e-mail Joe explained:

[T]he character’s last name is Vander Meer; I give him no first name. The name itself means “from the lake (or sea)”—an underwater man. I didn’t know this when I named him, though; the name just surfaced (!) one day in what became the eponymous first poem. I think I was influenced by Louis Simpson, whose poems I was reading at the time; he has a harrowing one called 'Vandergast and the Girl', and in the original edition I included lines from that poem as an epigraph from that poem: “What do definitions and divorce-court proceedings / have to do with the breathless reality?”

“Sunken like a river rock”—this really struck me because I have a whole series of poems I refer to as The Drowning Man Poems which revolve around a man who’s submerged in emotions, who feels like he’s drowning but never actually drowns. The word ‘drown’ appears four times in this collection and there are eighteen references to water as well as numerous references to seas, waves, floods, rivers, lakes and streams.

It’s on nights like this he pours himself into his blue notebook:

Nights

of wandering mindlessness...images

gushing forth, lovely and terrible

by turns....

This has to end somewhere. And it does in ‘VANDER MEER’S DUPLICITY’:

Vander Meer at the mirror, mouth

propped wide with a gun barrel

index finger, thinking:

“easeful death”...playing

homo ludens to the hilt. Who was it

said, a good poem always takes

the top of one’s head off?

Emily Dickinson said, “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry,” in case you wondered. Homo Ludens or Man the Player is a book written in 1938 by Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga. It discusses the importance of the play element of culture and society. Is Vander Meer a player? It depends what you mean by ‘player’. He’s not a player as in a powerful participant in some major concern, a man to be reckoned with. Nor do I think the definition in the Urban Dictionary fits here either:

A male who is skilled at manipulating ("playing") others, and especially at seducing women by pretending to care about them, when in reality they are only interested in sex. Possibly derived from the phrases "play him for a fool", or "play him like a violin". The term was popularized by hip-hop culture, but was commonly recognized among urban American blacks by the 1970s.

But he is still playing. What Huizinga says at the start of his book is noteworthy though:

In play there is something "at play" which transcends the immediate needs of life and imparts meaning to the action. All play means something. If we call the active principle that makes up the essence of play "instinct", we explain nothing; if we call it "mind" or "will" we say too much.

There are numerous theories about play but any man who’s having an affair is playing with fire. You tell me one kid who doesn’t like to play with fire though. Games have rules, even the games kids play where they make them up as they go along, and what’s the point of a game if there’s not a winner? And if there’s a winner there have to be losers.

It turns out though that the blue notebook is not the only thing Vander Meer’s been writing since he found himself alone; there’s also, apparently, “a cracked memoir he calls Bed of Coals”.

And so ends what I’m calling the ‘objective poems’. They’re bullet points really. They bring us to an ending but endings are only convenient stopping points for storytellers; there’s always more to tell. Maybe when we read the poems from the blue notebook things will become clearer.

![Tryptich I - John Ranson Tryptich I - John Ranson]()

The subjective poems (the poems from the blue notebook)

There are twenty-three of these beginning with one dated March 22nd. The tone here is quite, quite different. For example here’s the first poem in its entirety:

Stop Slaughtering Baby Seals or No More Nukes—

pathos of loving what we can’t love enough.

“When they split up,” some voice at the office,

“he joined The Alliance to Protect Snail Darters.

She worked door-to-door for Z.P.G.” Today,

following a night of smashed glasses

and food-slopped floors, our three-year-old

stared down my bitter breakfast silence:

“You’re not screaming now.” My eyes burned wet

as an oil-slicked dolphin’s.... Where are you,

Committee to Preserve Self-Devouring Spouses?

Yet I have kissed her mouth most tenderly—

mouth, breasts, curve of belly...cavorting

in a surf of sheets. And later, breathing

to sleep in the depths, I’ve dreamed in slogans:

No More Nukes! Stop the Slaughter! Save the Whales!

Quite the rant and confusing as hell. The people at the office are talking about a breakup in the past tense and yet Vander Meer’s still having breakfast with his kid in the morning (who we now know is about three) after what looks like a serious row with his wife the night before. So clearly—okay, maybe not so clearly—his work colleagues are talking about some other couple.

On June 20th Vander Meer’s clearly still at home with his wife. A poem entitled ‘Lifting My Daughter’ provides the evidence:

As I leave for work she holds out her arms, and I

bend to lift her...always heavier than I remember,

because in my mind she is still that seedling bough

I used to cradle in one elbow. Her hug is honest,

fierce, forgiving.

On June 21st he writes a poem called ‘Long Distance Call’. Since no one is named in these poems and the rest of the players are all women—his wife, his daughter, his lover—you really do have to pay attention to the context to work out who the ‘shes’ and ‘hers’ are. I’m assuming here he’s talking about his lover because he talks about one breath…

drawing us into a room

where we lie moving

slowly at first

tongue to tongue

in the house of longing

They’re still there three weeks later:

July 9

from the Blue Notebook

In bed we listened

to sleepwalking rain

drawn to the window

by your wetness

And they’re still at it on the 15th:

Too treble for ears, a gracenote’s summons

feathered through our brains, piped us

to the pied guestbed quilt. Spreading towels

against stain, she baptized my bald homage

in water holy past pun or punishment. Our method—

pure rhythm; as a rosined bow thrills the gut

to gladden the soul, so the lingua franca,

pentecostal stammering of our hearts

renewed us.

They know what they’re doing. They know other people will be affected—“[s]pouses, friends, hurt families”—but now is not the time to think about all that; they’re caught up in The Game (hard not to think about Cocteau’sLes Enfants Terribleshere). It’s noteworthy that they adopt the rhythm method of birth control even though she sounds like a lapsed Catholic. It’s perhaps worth mentioning that in Joe’s ordering of the collection these poems are presented in reverse order, from the height of the affair reading back to its beginning.

By August 8th the passion seems to have died down:

Yet our words are clinical,

sobering. We’ve sworn off love,

taken the cure...and toast

ourselves with chilled mineral water—

The affair would appear to have lasted a month which is backed up by what we learn later in one of the reflective poems, ‘Snapshots’:

That month’s like a peach cut in half

Even the deep ragged wound is sweet

although in ‘Fullness’ he talks about five weeks:

Living on beer and coffee, we

burned off ten pounds each in half

as many weeks (in love, the body

grows lean to feed the heart).

We know from the objective poems that the breakup happens sometime in August but none of the dated poems from the blue notebook of that period deal with it although from what I remember of my own first breakup that’s not that surprising; real life issues get in the way. By September 23rd the reality of his situation is starting to hit home though:

September 23

from the Blue Notebook

Cinching my belt to the fourth

notch—and still it’s loose!

(How many weeks now

since I’ve touched you?)

These early poems are quite detached. The reality of what’s happened has hit him but only on an intellectual level. By December 22nd he’s starting to wallow; it is the Christmas period after all and a hard time for the newly separated and divorced:

I’d like to breathe,

but can’t. My jaw goes stone at the hinge.

Say what I feel? All words are trash

in my throat’s choked swash;

emotion’s current will not flow—

By January he’s starting to become self-pitying. And his Valentine’s Day poem is dark:

Sworn vows gone into the ground with your love;

from us the world inherits nothing but dust.

Indeed February’s a bad month. No less than four poems. As March comes round he’s starting to realise how useless his poetry is:

Am I cruel,

then? Draining our lives into language

where even joy is suffering...? My love,

I suffer words for the normal joy they redeem—

and therefore hope they’ll make you suffer:

you, kinder than my heart can stand.

The poems in this section are a mixture of lyrical and narrative. Only their dates really provide any context. We have roughly six months before the breakup and six months afterwards. Yes, they do fill in some of the details but it’s hard to be sure.

![Nervous Apparition - John Ransom Nervous Apparition - John Ransom]()

The reflective poems

There are twenty-seven poems in this section and it’s impossible to know in what order they were written. The first ‘Fighting Grief’ is helpful. It tells us that his lover was married at the time of the affair. I’d misread the January 29th poem, assuming when Vander Meer referred to “her husband” he was referring to himself in the third person. This is what was so confusing, not knowing which woman was being referred to but I don’t suppose it’s unreasonable for him to miss both his wife and his mistress. What is curious in this poem is that he says he’s fighting not guilt as one might’ve expected but “grief”. What is he grieving? The end of his marriage?

‘Lethe’ provides some clarification. It’s describing something that happens in April, so a couple of months before the affair:

“You pulled back,” said his wife. “You

were passionate, then—just gone.”

The sky curved above their house like a tree,

ash or willow, thick-leaved, many-branched.

She said, “Is there something wrong?”

[…]

He thought, What could be wrong?

By the time he responds his wife’s dozed off. He’s been reprieved. In Greek mythology, Lethe was one of the five rivers of Hades It flowed around the cave of Hypnos and through the Underworld, where all those who drank from it experienced complete forgetfulness. Lethe was also the name of the Greek spirit of forgetfulness and oblivion, with whom the river was often identified.

The poems in this section are more level-headed than those in the blue notebook. They’re not, however, detached reportage as in the objective poems. One of the most moving is this one:

Pausing Outside My Apartment

Sun must be filling the room.

One thin ray is streaming

from the peephole.

Daylight and dust.

You can feel the earth

turning under you at times.

The roundness of anguish.

Daylight and dust.

It’s like a dream.

The key turns my hand.

I open my life and go in.

This poem more than any other in this collection struck a chord with me. Although I wasn’t to blame for the breakup of my own first marriage there was a point before we split up that the reality of my situation hit me. This was how I expressed it at the time:

A MARRIAGE

One day he tried too hard and broke it.

He patched it up

and it still worked,

though not as well.

The wheels still went round.

No one noticed any change

till one day it fell to pieces

and they all wondered why.

27 June 1982 – 23 September 1982

The first date is when I wrote the poem. The second was the day my wife left me. I believe very strongly that all poetry is completed by its readers. There will be some people who’re reading this just now who have never been married and have never even broken up with a girl or boyfriend. They’ve never experienced a pivotal moment like this. Reading on I came across ‘Detour’, a prose poem I suppose although I’ve never been good at differentiating between flash fiction and prose poetry, which I also related to. Vander Meer’s driven miles to sit outside this woman’s house. He’s listening to the radio or trying to:

The radio’s garbled music crackles in and out of its channel. No use twisting the knob: something inside is loose—a broken connection....

“Love,” he said, “is a way of being. It includes emotions. Attitudes. Values. It includes ideas. This is why we can’t repress love. It absorbs the repression, which changes the relationship but doesn’t destroy it.”

I click off the radio…

After he gets to the woman’s house—we learned in the June 3rd entry in the blue notebook that it’s a long drive, “a hundred miles [from] what’s left of home”—all is dark so he leaves a note and as he’s driving away he thinks (presumably about his wife and not this other woman): Something inside is loose. … Something inside is broken. This is exactly how I felt with my first marriage. Actually when I read this piece the first time I misread the last line. I read “Something inside love is loose. Something is broken.” That’s how I felt.

Just as I wrote my marriage poem months before the actual official breakup Vander Meer starts making entries in his notebook. In the poem ‘On Opening the Blue Notebook’ he writes:

When I picture you, I hear

such gears engage—as if thought

were a kind of wheelwork, routinely

spinning dreams into images,

love into dreams....

Interesting that both Joe and I would compare a marriage to a machine, and one that can break down.

Of course looking back it’s easy to misremember things. We see that in ‘Recalling the Solstice’ when he writes:

Grass and junipers grey with frost

just before dawn. The dark grey too,

with a mist drifted off the river.

(In language it seems symbolic,

but out my window it was only cold

cloudiness turned up hauntingly

over night.)

and also in ‘A Box of Snapshots’. As he looks at a photo of him standing in the shadow of a willow tree he thinks:

[I]t’s me as I am

in the willow tree’s shadow, me

in the shade of my parent’s house—

but lit by a knowledge so bright

I have to shut my eyes to see.

One might think when we reflect we become more level-headed and indeed the poems in this group are calmer and more reflective but there’s also a danger that the imagination will take over. I’m no brain scientist but the evidence is building: memories and imaginings are two sides to the same mental function whatever you want to call it, cognition I suppose. If we’re not careful we attribute meaning to things that essentially were meaningless acts in the first place which is not to suggest they were not emotive acts.

The title poem comes next, ‘Bed of Coals’, which is also, remember, the title of his “cracked memoir”. It’s set in June and in it he’s a carny; he runs The Calypso:

thirty cars held to a hub

by hydraulic spokes whose festive lights flash

as the motor drives it all around.

It’s a place full of activity and noise and yet he describes it as the eye of the storm, an oasis in all this chaos where he starts “to hear her breathing beyond the noise”. This is similar imagery to that used in ‘Drunk Again in the Dark Grass’ where he writes:

For once I want to listen

past the waves. To fall silent,

let moonlight soak me to the bone!

He’s not a carny, he’s a copy editor. For once this is not a dream because he tells us right at the very start that he can’t sleep; he’s tossing “like a flame on [a] bed of coals.” Obviously this isn’t the memoir. Perhaps, however, this is where he got the title for the memoir.

‘Fullness’ is an interesting poem since clearly Vander Meer’s lost much getting to this point. The second half reads:

I keep

trying to swallow the fishbone

moments of the past—as if

I could live on loss.

Yet it isn’t loss,

but fullness recalled

to fullness again: my heart

no starveling, though it hurts—

aches like a bulging net

I strain to raise: memories

hauled up over and over, quick

and seething in the drowning air.

I have to say I’ve read these few lines over and over again. I feel they may well be pivotal but I’m not sure I get them. It’s an awkward sentence which doesn’t help. Try reading it parsed as prose:

Yet it isn’t loss, but fullness recalled to fullness again: my heart no starveling, though it hurts—aches like a bulging net I strain to raise: memories hauled up over and over, quick and seething in the drowning air.

‘Beyond Sorrow’ was another poem that reminded me of one mine. Joe writes:

In the crowd a girl’s face

not yours but eyes

like yours

[…]

enough now

to love you in other faces

and feel my heart silently rise

inside me

I wrote:

When we broke up

I wondered where he'd go:

He went to look for me

in other women.

I think it’s not unlike what happens when your wife falls pregnant. Suddenly there are these pregnant women everywhere as if it’s a fashion thing and your wife’s the trend-setter. When you no longer have access to a loved one, can no longer touch her on a whim or see her naked suddenly that’s what you want and that’s what you look for, more of the same. You forget all the reasons why things didn’t work out with her. You want to press RESET and do it all over again and maybe this time it’ll work out.

‘The Voice of Reason’ tries to be heard:

The error, of course, is thinking

there’s a way to live your life,

as one might “drive a car.” Life

is what drives you. Such a stinking

shame...having so little control!

And yet all the time resisting it—

September comes round in ‘This Day’, the final poem in this group and the final poem in the collection and where do we find Vander Meer?

On the corner, anachronistic in mid-September,

a girl in jogging shorts...tanned legs

glistening with sparse, honey-pale down,

her thighs strong, smooth as buttered rum.

How to keep from staring through her to find you?

September when? Not the September following the August when his wife told him to go. No, this is the September after that most likely. A year and a bit on. His life has fallen to pieces. He’s played the game and lost. He’s hit bedrock. He’s stuck a gun in his mouth and now he’s ready to get back on the bike again. Too many of us define ourselves through other people, through our parents, our spouses, our heroes. Is history going to repeat itself?

![Skeltz2 - John Ransom Skeltz2 - John Ransom]()

The collection as a whole

After having chopped up this collection to suit my ends—albeit with the approval of the author—I then went back and reread it from the beginning in the order he had chosen. It all boils down to a single word: intent. How do you read a single Joe Hutchison poem let alone an entire book of them?

Joe has a few things to say on this subject of intention. From his blog:

There may be many other good reasons to read, but I don't see how any reader can pretend that the author's intentions are irrelevant. They are always the substance and the structuring motive behind the work. – A Conversation in Progress II

Surely the primary purpose of reading any work is to understand its author’s intention (again, broadly conceived), in the hope of better understanding our own. – A Conversation in Progress

[W]e owe the authors we care about the duty of intentional engagement. If they’re going to speak to us, we have to bring them our questions: we have to inquire about their intentions and look to their texts, their lives, and their historical periods — and, of course, our own honest responses to their work — for help. Otherwise it’s all just a frivolous game. – A Conversation in Progress

So what’s Joe’s intent here? In his essay ‘I Have Seen the Future and It Is Prose’ Joe writes that he believes that “poetry … exists in order to express those complex areas of the individual psyche that ordinary prose … is not designed to express” and in this interview:

Mindfulness is another word for love. It’s passionate and purposeful. It engages. If we think about what it’s like to fall in love, we’ll notice that it disarranges our lives. All the old habits and routines break down!

[…]

Mindfulness is what poetry is all about, of course. Poetry is the result of the poet reclaiming awareness from habit and routine and putting the result in words that can help a reader do the same thing. The poet’s long dead, but through engagement with the mindful poem, the living reader can reclaim awareness in his or her own life. Poetry is a kind of sympathetic magic.

And in 'Fists and Flashing Eyes':

[A]n authentic reading of an authentic poem influences the reader’s idea of reality …Reading it is a dangerous activity. For if each new poem, each new imaginatively structured byte of language, influences our experience of the program — why, individuals might actually come to believe that their subjective experience of the world is more real than the one the information society’s selling.

Intent is clearly not a simple thing. The problem is made clear in the first quote when he uses the adjective ‘complex’. Complex things are, by their very nature, hard to express is simple terms or when they are they lose much in the translation, e.g. E = mc2. Human emotions can be similarly reduced— fear, joy, love, sadness, surprise, anger—but these simplifications are just as unhelpful. Emotions have to be experienced. And even then they can be hard to pin down. I’m almost fifty-five and I still don’t understand why I’ve done half the things in my life. So why should Joe (or his proxy Vander Meer) be any different?

I only had one question when I first opened this book. It was a rather vulgar one: What’s the heck’s this all about? I refined it quickly enough and soon I had a whole ... what is the collective noun for questions? ‘shitload’ I think … some of which I’ve managed to answer above. But one I haven’t been able to answer is: What was Joe’s intent? I sat down with the intention of understanding as much of this text as I could. What I discovered was that I was not alone in thinking the way I do. Joe—assuming there is some autobiographical element to this collection—and I have been in some of the same places or similar enough. I’ve never put a gun in my mouth but I have hit rock bottom.

In his essay ‘Plains Light’ Joe puts forth the proposition that all writers are influenced by their sense of place with the possible exception of Ezra Pound—“[t]here’s no trace of Idaho in Pound’s poetry”—but Glasgow’s a million miles away from Denver (actually it’s 4375 miles) and I have to say I imposed my own environment on the poems. Never, not for one second, did they make me think of anywhere but an abstract here—mentions of “Oregon’s coastal pines”, “a shaggy pasture / in Nebraska” or “the Pacific breeze” slipped past me and it wasn’t until I went back through the book specifically looking for them that I gave the notion of place a second thought—although I think that’s to their advantage. Marriage is a universal concept and there won’t be a country on the planet where someone’s not cheating on their spouse right this minute.

Memory is collagelike. Mine’s a dog’s breakfast if I’m being honest. But an honest recollection is never going to be neat. It’s going to be kluged together from misremembrances and imaginings with the odd bone fide fact thrown in for good measure like the fact that his wife’s iron’s a Sunbeam (there’s got to be something about light going on there). Of course the things we forget to remember are trivialities (to us) like what we looked like at the time. Vander Meer’s description of himself is “passably human, almost alert” and that’s it. There’s a lot we don’t ever find out about Vander Meer, we know he’s “no Christian” but basic stuff like how old he is is bypassed; we learn that he once owned a VCR and has seen Victor Victoria but he never sees fit to mention his daughter’s name. This is, of course, typical of most poetry but I would’ve liked just a bit more exposition here. What, for example, are we to make from his “80 proof adolescence”?

On the whole though the poetry here is very accessible—I’m talking about individual poems here, many of which have already been published on their own—and there’s a lot to enjoy in this collection although it does require time spent on it which most readers won’t be willing to do. Their loss you might say and perhaps but I don’t think the ordering of the poems will help many. Since I’d agreed to write about the collection I was committed to getting to the bottom of it. Few readers will be as driven. But that doesn’t mean you’ll waste your time with this book. Far from it. And just because the poetry is accessible does not mean it’s superficial. The Syrian poet Adonis has reportedly said, “Real poetry requires effort because it requires the reader to become, like the poet, a creator. Reading is not reception.” This chimes with something Joe’s old English teacher told him and which he’s clearly taken on board:

She insisted that poetry, if read with intense imagination instead of simply being registered and sorted like data in a well programmed computer, changes the way we experience the world. Themes, symbols, the techniques of prosody, all are secondary to the fact of the poem as a structured experience. “The reader’s responsibility,” said Mrs. Van, her flashing eyes taking in the whole classroom full of college-bound faces, “your responsibility is to live through that poem with as much imagination as you can muster.”

Readers with some imagination and the right baggage will find much here they can relate to. And if, like me, only one poem really calls out to you I don’t think Joe will be unduly disappointed.

You can read a selection of poems from the book here.

***

![JoeAspensOffCenterCrop300 JoeAspensOffCenterCrop300]() Bed of Coals is Joseph Hutchison’s third full-length collection and was originally published in 1995 by the University of Colorado Press. It was selected by Wanda Coleman as the winner of the 1994 Colorado Poetry Award. The cover art was created by California artist John C. Ransom and it’s from his site I’ve borrowed the illustrations for this essay; they are not a part of the book.

Bed of Coals is Joseph Hutchison’s third full-length collection and was originally published in 1995 by the University of Colorado Press. It was selected by Wanda Coleman as the winner of the 1994 Colorado Poetry Award. The cover art was created by California artist John C. Ransom and it’s from his site I’ve borrowed the illustrations for this essay; they are not a part of the book.

In total Joe has published some fifteen collections of poems, including Marked Men, Thread of the Real and The Earth-Boat. He co-edited, with Andrea L. Watson, the FutureCycle Press anthology Malala: Poems for Malala Yousafzai, proceeds of which benefit the Malala Fund to support girls’ education. He makes his living as a commercial writer and as an adjunct professor of graduate-level writing and literature at the University of Denver’s University College. He and his wife, yoga instructor Melody Madonna, live in the mountains southwest of Denver, in fact he’s lived nearly all his life “on the western margin of the plains, between the gnarled wall of the Rockies and the Colorado flatlands.”

He’s probably more like Chance from Jerzy Kosinski'sBeing Therethan Mork if I’m being honest. At least at first. His parishioners—not sure if Buddhists have parishes—include some very wealthy people who (and this is not entirely their fault) have some very … let’s just go with American … ideas about what Buddhism is all about. Up until Oda’s arrival they’ve been happy to refer Buddhism for Dummies, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenanceand The Reader’s Digest Encyclopaedia of Religion for guidance:

He’s probably more like Chance from Jerzy Kosinski'sBeing Therethan Mork if I’m being honest. At least at first. His parishioners—not sure if Buddhists have parishes—include some very wealthy people who (and this is not entirely their fault) have some very … let’s just go with American … ideas about what Buddhism is all about. Up until Oda’s arrival they’ve been happy to refer Buddhism for Dummies, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenanceand The Reader’s Digest Encyclopaedia of Religion for guidance:  not a very interesting person. The only thing of consequence that happens to him is as a young boy when his parents are killed in a fire that his depressive father may or may not have started deliberately. So, although he doesn’t really realise it, part of his quest is for family and that’s what he finds in America. You can choose your friends but not your family, so the saying goes. I guess that truism applies to spiritual families too.

not a very interesting person. The only thing of consequence that happens to him is as a young boy when his parents are killed in a fire that his depressive father may or may not have started deliberately. So, although he doesn’t really realise it, part of his quest is for family and that’s what he finds in America. You can choose your friends but not your family, so the saying goes. I guess that truism applies to spiritual families too.  An American born in Portugal and raised in Switzerland, Richard Morais has lived most of his life overseas, returning to the States in late 2003. He was stationed in London for 17 years asForbes’ European Correspondent (1986 to 1989), Senior European Correspondent (1991 to 1998), and European Bureau Chief (1998 to 2003.) He wrote numerous cover stories for Forbes, from billionaire profiles to corporate dissections, but he was best known for unusual business stories on everything from the hashish entrepreneurs of Holland, to the ship breakers of India, to the human organ traders of China. Morais has won six nominations and three awards from the London-based Business Journalist of the Year Awards, the industry standard for international business coverage.

An American born in Portugal and raised in Switzerland, Richard Morais has lived most of his life overseas, returning to the States in late 2003. He was stationed in London for 17 years asForbes’ European Correspondent (1986 to 1989), Senior European Correspondent (1991 to 1998), and European Bureau Chief (1998 to 2003.) He wrote numerous cover stories for Forbes, from billionaire profiles to corporate dissections, but he was best known for unusual business stories on everything from the hashish entrepreneurs of Holland, to the ship breakers of India, to the human organ traders of China. Morais has won six nominations and three awards from the London-based Business Journalist of the Year Awards, the industry standard for international business coverage.

Maria Konnikova

Maria Konnikova