If the reader prefers, this book may be regarded as fiction. But there is always the chance that such a book of fiction may throw some light on what has been written as fact. – Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

When you read you forget. You’re forgetting right now. Reading is an act of forgetting but there are levels. Whilst reading you temporarily forget the outside world and become absorbed in the text before your eyes but as your eyes scan the page in front of you, you also almost instantaneously begin to forget what you’ve read. You carry the gist of what you’re read from page to page but if asked to remember even a single sentence from the preceding page most would be hard pressed to do so. We let go so easily.

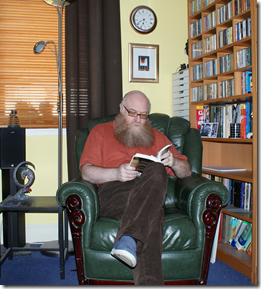

Memory is an issue with me and so any texts that deal with memory issues are always of more interest to me than others and so from the very beginning of this book I found myself empathising with the narrator—not to be confused with the author although they could well be twins—and his inability to remember very much about any of the books he’s read throughout his life. When I first joined Goodreads I decided to go through the books in my cupboard, the old ones I’ve been carting around for decades, and enter them in the system to start me off and I was appalled to note how little I could dredge up from the depths of my mind. I had, for example, read four books by Nabokov when in my early twenties and could remember nothing bar the titles.

In ‘The Boy’s Name Was David’ the third of the four pieces of fiction in this book—Murnane doesn’t talk about his writing in terms of novels or stories—we’re introduced to a man who was for a time an English teacher and he makes an important point about reading, at least according to Joyce:

As a teacher, he had been fanatical in urging his students to think of their fiction, of all fiction, as consisting of sentences. A sentence was, of course, a number of words or even a number of phrases or clauses, but he preached to his students that the sentence was the unit that yielded the most amount of meaning in proportion to its extent. If a student in class claimed to admire a piece of fiction or even a short passage of fiction, he would ask that student to find the sentence that most caused the admiration to arise. Anyone claiming to be puzzled or annoyed by a passage of fiction was urged by him to find the sentence that had first brought on the puzzlement or the annoyance. Much of his own commentary during classes consisted of his pointing out sentences that he admired or sentences that he found faulty. At least once each year, he told each class an anecdote that he had remembered from a memoir of James Joyce. Someone had praised to Joyce a recent novel. Joyce had asked why the novel was so impressive. The answer came back that the style was splendid, the subject powerful…Joyce would not listen to such talk. If a book of prose fiction was impressive, the actual prose should have impressed itself on the reader’s mind so that he could afterwards quote sentence after sentence. [bold mine]

I managed to remember the first three sentences of this article in their entirety. Ask me in an hour’s time and it’ll be a very different story.

What happens when we read? No doubt whole books have been written on the subject although this article is interesting when it comes to the subject of fiction. It’s not something we think about. We pick up a book, locate where we left off and begin. But begin doing what? When we put down a book we say we’ve finished it but what does that mean? Samuel Johnson noted: “A writer only begins a book. A reader finishes it.” He meant something different though; he believed that a reader adds to the written word and oftentimes when a book fails the lack is with the reader and not its author: I can tell you here and now that I was too young to appreciate the Nabokovs I read as a young man.

Murnane opens the first work of fiction in this book with a famous quote:

After a certain age our memories are so intertwined with one another that what we are thinking of, the book we are reading, scarcely matters any more. We have put something of ourselves everywhere, everything is fertile, everything is dangerous, and we can make discoveries no less precious than in Pascal’s Pensées in an advertisement for soap. MARCEL PROUST, Remembrance of Things Past

I’m not sure what age Proust was thinking about but I believe—and I suspect Murnane would agree—that this process begins at a very early age. Images are a big thing with Murnane and he gets a great deal of satisfaction from discovering “at least once during the writing of [a piece of] fiction a connection between two or more images that had been for long in his mind but had never seemed in any way connected.” In the second piece of fiction in this book, ‘As It Were a Letter’, he talks about a time when he was eleven:

If [he] had been asked at the time what were the chief dangers of the modern world, he would have described in detail two images that were often in his mind. The first image was of a map he had seen a year or so previously in a Melbourne newspaper as an illustration to a feature article about the damage that would be caused if an Unfriendly Power were to drop an atomic bomb on the central business district of Melbourne. Certain black-and-white markings in the diagram made it clear that all persons and buildings in the city and the nearest suburbs would be turned to ash or rubble. Certain other markings made it clear that most persons in the outer suburbs and the nearer country districts would later die or suffer serious illness. And other markings again made it clear that even persons in country districts rather distant from Melbourne might become ill or die if the wind happened to blow in their direction. Only the persons in remote country districts would be safe.

The second of the two images mentioned above was an image that often occurred in the mind of the founder of Grasslands although it was not a copy of any image he had seen in the place he called the real world. This image was of one or another suburb of Melbourne on a dark evening. At the centre of the dark suburb was a row of bright lights from the shop windows and illuminated signs of the main shopping street of the suburb. Among the brightest of these lights were those of the one or more picture theatres in the main street. Details of the image became magnified so that the viewer of the image saw first the brightly lit picture theatre with a crowd milling in the foyer before the beginning of one or another film and next the posters on the wall of the foyer advertising the film about to be shown and after that the woman who was the female star of the film and finally the neckline of the low-cut dress worn by that woman. This image was sometimes able to be multiplied many times in the mind of the viewer, who would then see images of darkened suburb after darkened suburb and in those suburbs picture theatre after picture theatre with poster after poster of woman after woman with dress after dress resting low down on breasts after breasts.

This is very typical of Murnane. When he reads he is completely absorbed with the images that appear in his mind, some generated by the text obviously enough but others that are responses to what he’s been reading. Fiction is very important to him. It’s the environment that’s most suitable for the kind and level of thinking he gets the most out of. He notes that when a young man he actually “preferred to the visible world a space enclosed by words denoting a world more real by far.”

In ‘The Boy’s Name Was David’ he talks about a story written by one of his students. As an old man he’s been looking back on the various stories he’s read and graded over the years—over three thousand—and realises that he can remember very little of any of them. So he devises a kind of game, a race if you will—the winner of which will receive the imaginary “Gold Cup of Remembered Fiction”—to see which one he can recall most clearly:

The fifth contender was a sentence: the opening sentence of a piece of fiction. A few vague images hung about the man’s mind whenever he heard the sentence in his mind, but they meant little to him. The man was not even sure whether the images had arisen when he had first read the fiction that followed on from the opening sentence or whether he had imagined them, so to speak, at a much later date. The man seemed to have forgotten almost all of the fiction except for the opening sentence: The boy’s name was David.

[…]

The boy’s name was David. The man, whatever his name was, had known, as soon as he had read that sentence, that the boy’s name had not been David. At the same time, the man had not been fool enough to suppose that the name of the boy had been the same as the name of the author of the fiction, whatever his name had been. The man had understood that the man who had written the sentence understood that to write such a sentence was to lay claim to a level of truth that no historian and no biographer could ever lay claim to. There was never a boy named David, the writer of the fiction might as well have written, but if you, the Reader, and I, the Writer, can agree that there might have been such a boy so named, then I undertake to tell you what you could never otherwise have learned about any boy of any name. [bold mine]

Many times throughout these texts Murnane pauses to remind the reader that what they’re reading is a work of fiction. For example:

Since the previous sentence is part of a piece of fiction, the reader will hardly need to be reminded that the man mentioned in that sentence and in earlier sentences is a character in a work of fiction and that the newspaper clipping and the note mentioned in some of those sentences are likewise items in a piece of fiction.

There is at least one good reason for this. More than any other writer Murnane draws on his own life experiences as a basis for his fiction and it’s tempting to imagine what you’re reading is autobiographical in nature—it is undoubtedly semi-autobiographical—but the simple fact is that even if it were wholly autobiographical and as accurate an accounting as he was capable of producing it would still be fiction: we fictionalise it as we read it. I have never been to Melbourne. I’ve seen a few photos and some films (I watched a documentary about Murnane, Words and Silk – The Real and Imaginary Worlds of Gerald Murnane, which featured the city, for example) but the bottom line is that Melbourne might as well be Narnia as far as  I’m concerned. Murnane exists in my imagination in exactly the same way and I exist in his imagination; I have a copy of Barley Patch signed to me and he got the city I live in wrong. As Murnane puts it, in A Million Windows, “Today, I understand that so-called autobiography is only one of the least worthy varieties of fiction extant.”

I’m concerned. Murnane exists in my imagination in exactly the same way and I exist in his imagination; I have a copy of Barley Patch signed to me and he got the city I live in wrong. As Murnane puts it, in A Million Windows, “Today, I understand that so-called autobiography is only one of the least worthy varieties of fiction extant.”

For me the most captivating piece of writing in this volume was the opening one, ‘A History of Books’, which consists of twenty-nine sections that trace his reading throughout the years and how little he finds he can remember of any of those books. It also looks at why he was reading. He’d decided he wanted to be a writer—he’d even taken two years off work letting his wife support him so that he could have the space to tackle this ambitious project—but what he discovers as he reads (and as he attempts to write) is what kind of writer he is. One like no other. Simply telling stories was not for him. He felt “as though writing fiction was too easy. It seemed to [him] the easiest of tasks to report image-deeds done by image-persons in image-scenery or even to report the image-thoughts of the image-persons.” Hence his unique approach to writing.

If this is the first book by him it will take you a while to get into step with him. He writes with great precision but also manages to be incredibly vague at times to. A simple example:

His surname ended with the fifteenth letter of the English alphabet.

I bet you just counted the letter on your fingers. It’s what I did. I didn’t even have to think about it. But you can’t say he’s not been precise. And he often directs the reader’s attention to things he’s written previously (or is about to relate) with comments like “the young woman mentioned in the first sentence of the previous paragraph”, “[t]he man aged sixty and more years had never read any sort of report of the fictional events reported in the previous five paragraphs of this work of fiction” and “[e]ach of the four previous paragraphs reports details of a central image surrounded by a cluster of lesser images that had arisen from several sentences of one or another piece of fiction.”

At the end of the book the publishers provide a list of the authors of the books referred to in ‘A History of Books’ are believed to include. I would discourage you from checking it until you’ve finished the piece. That said they don’t mention the actual books he’s talking about. Some were obvious—he provides the occasional quote which you can easily google—and he even names one (although he does so in the original German) but a number are very obscure. It seems as a young man he and his friends were attracted to esoterica:

The man and his friends liked to seek out and to read little-known books of fiction, especially books translated from foreign languages, and then to announce to one another that he or she had discovered a neglected masterpiece, one of the two or three greatest books of fiction that he or she had read.

Here’s an example:

An image of a man and an image of a young woman appeared at the base of a tall image-cliff. These images appeared in the mind of a certain young man while he was sitting beside a campfire at the base of a tall cliff and trying to explain to a certain young woman what he remembered having read in certain passages of a certain book that he considered, so he told the young woman, a neglected masterpiece of English literature. Since the young man spoke as though the image-persons were actual persons, they will be thus described in the following paragraphs.

The image-cliff was not a bare rocky cliff such as might have overlooked a bay or a seacoast but a steep embankment overgrown with grass and bushes and forming one side of something that was reported in the so-called neglected masterpiece as being a dingle, which word the young man had never looked for in any dictionary, preferring not to have to call into question the images that had first appeared in his mind while he was reading a work of fiction. At the base of the cliff was mostly level grass shaded, at intervals, by clumps of bushes. Near one such clump a small tent was pitched. Perhaps ten paces away, near another clump, a second tent was pitched. About halfway between the two tents, a kettle of water hung above a campfire. One of the tents belonged to the man mentioned and the other tent to the young woman mentioned in the first sentence of the previous paragraph. Both the man and the young woman were noticeably tall, and the young woman had red hair.

The man and the young woman had lived in their respective tents since their first meeting, which had taken place several weeks before. At that meeting, the young woman had struck the man but had later made peace with him. During the weeks when the young woman and the man had lived in their tents, they had often taken their meals together or had drunk tea together at the campfire between the tents. At such times, they had debated many matters, and the young woman had sometimes threatened to strike the man. Sometimes, beside the campfire, the man had persuaded the young woman to learn certain words and phrases in the Armenian language, which the man had learned from books for no other reason than that he felt driven to learn foreign languages. At one time, beside the campfire, the man had persuaded the young woman to conjugate in several of its tenses and moods the Armenian verb siriel, I love. In the course of this lesson, the man and the young woman were obliged to speak, in the Armenian language, such sentences as ‘I have loved’, ‘Love me!’ and ‘Thou wilt love’. At a later time, beside the campfire, the man proposed to the young woman that he and she should marry at some time in the future and should then go to live in America. At a later time still, the young woman left the dingle without the man’s knowing and did not return. A few days later again, the man received from the young woman a long letter telling him, among other things, that she was setting out alone for America and that she had declined his proposal of marriage because she believed he was at the root mad.

The book in question is Isopel Berners by George Borrow, specifically the events of chapter fourteen. Not a book I suspect many will have heard of. Not an author I suspect many will have heard of. But none of that’s important. Were I to list all the books I’ve ever read I’m sure there will be a few oddities in there which are unique to me and form part of the image bank that I draw on every time I read a book. I, for example, to the best of my knowledge have only read one book by an Icelander—Stone Tree by Gyrðir Elíasson. Murnane has also read at least one, an “English translation of a long work of fiction that had been first published in the Icelandic language in Reykjavik in the year before” he was born—so that would be in 1938. My best guess would be Halldór Laxness’s World Light. Either way Murnane will have his fictionalised version of Iceland in his head and I will have mine.

The book in question is Isopel Berners by George Borrow, specifically the events of chapter fourteen. Not a book I suspect many will have heard of. Not an author I suspect many will have heard of. But none of that’s important. Were I to list all the books I’ve ever read I’m sure there will be a few oddities in there which are unique to me and form part of the image bank that I draw on every time I read a book. I, for example, to the best of my knowledge have only read one book by an Icelander—Stone Tree by Gyrðir Elíasson. Murnane has also read at least one, an “English translation of a long work of fiction that had been first published in the Icelandic language in Reykjavik in the year before” he was born—so that would be in 1938. My best guess would be Halldór Laxness’s World Light. Either way Murnane will have his fictionalised version of Iceland in his head and I will have mine.

We’ve talked a lot about fiction—the word appears in the book over two hundred and fifty times—but what about non-fiction, facts? He has some interesting things to say on this subject. Two unrelated excerpts:

(Why did I write just then the expression a book of non-fiction? Why is the expression a factual book so seldom used? Is this our way of acknowledging that most seeming-facts are, in fact, fiction? And, if books of fiction are not called non-factual books, is this because we understand that most matters reported in books of fiction have a factual existence?)

[…]

The man who was aged nearly seventy years was making notes for a work of fiction in the belief that the power of fiction was sometimes able to resist, if not to overcome, the power of fact. The man understood that a fact could never be other than a fact, even though it might be reported in a work of fiction, but he believed that any fictional event or any fictional character might be said to have acquired a factual existence as soon as the event or the character had been reported in a published text.

You might be forgiven for thinking you were reading a book on philosophy rather than a work of fiction but this is very much philosophy-with-a-small-p. This is a guy trying to communicate how he sees the world. It sounds complex but then riding a bike sounds difficult when you try and put it into words and really for all this guy’s a writer his primary interest is in the visual, what he sees when he reads.

Although not arranged chronologically what we get in this book is a very specific kind of biography, from age eleven to nearly seventy; he’s seventy-five at the moment. Other of his works of fiction deal with different aspects of his life. As an addition to his existing canon I’d say it was invaluable but then I’m a fan as you can see from my articles on Tamarisk Row, Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs, Inland and The Plains. I’ve also read Barley Patch but never quite got round to writing about it.

The final piece of fiction in this volume is ‘Last Letter to a Niece’. I’ll mention it just briefly. This is a very different piece of writing. You’d almost think it was a story. And there’s a reason for this. It’s actually an adaptation “from one of the seven pages about the life and the writing of Kelemen Mikes in the Oxford History of Hungarian Literature.” Oddly, though, it fits with the tone of the rest of the book because the uncle in question has never seen his niece and so holds an imaginary image of her in his head (and from all accounts in his heart):

But I have not explained myself. I am interested in the appearance and deportment of young women in this, the everyday visible world, for the good reason that the female personages in books, like all other such personages together with the places they inhabit, are quite invisible.

You can hardly believe me. In your mind at this very moment are characters, costumes, interiors of houses, landscapes and skies, all of them faithful images of their counterparts in descriptive passages in books you have read and remembered. Allow me to set you right, dear niece, and to make a true reader of you.

A true reader. I’d like to think this is how Murnane sees himself and that his efforts in writing this book (as well as his others books) is to convert us into true readers too. In that respect this is the most evangelical of texts and yet somehow manages not to be at all preachy.

If you have read Murnane before this book will not disappoint. If you haven’t this isn’t actually a bad place to start. There’s stuff you won’t see as important—the marbles, the horse racing and his interest in Hungarian which he taught himself to speak late in life (see here)—but it’s not a great loss; the book stands alone just fine.

***

Gerald Murnane was born in Coburg, a northern suburb of Melbourne, in 1939. He spent some of his childhood in country Victoria before returning to Melbourne in 1949 where he lived since. He has left Victoria only a handful of times and has never been on an aeroplane.

Gerald Murnane was born in Coburg, a northern suburb of Melbourne, in 1939. He spent some of his childhood in country Victoria before returning to Melbourne in 1949 where he lived since. He has left Victoria only a handful of times and has never been on an aeroplane.

In 1957 Murnane began training for the Catholic priesthood but soon abandoned this in favour of becoming a primary-school teacher. He also taught at the Apprentice Jockeys’ School run by the Victoria Racing Club. In 1969 he graduated in arts from Melbourne University. He worked in education for a number of years and later became a teacher of creative writing. In 1966 Murnane married Catherine Lancaster. They had three sons.

His first novel, Tamarisk Row, was published in 1974, and was followed by nine other works of fiction. He’s also published a collection of essays, Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs.

In 1999 Gerald Murnane won the Patrick White Award. In 2009 he won the Melbourne Prize for Literature. He has since won the Adelaide Festival Literature Award for Innovation and has received an Emeritus Fellowship from the Literature Board of the Australia Council.

Patrick Modiano

Patrick Modiano

David Grossman

David Grossman

Julie Otsuka

Julie Otsuka

Chris Killen

Chris Killen