![]()

All books by Gerald Murnane, if you can find them, are fascinating. Obscure and fascinating. One feels as though the grit in one’s reading eye has been thoroughly cleaned out with…something. – Genevieve Tucker (comment made in a thread talking about difficult books)

In 2005 the publisher Giramondo—an independent university-based Australian literary publisher of award-winning poetry, fiction and non-fiction, renowned for the quality of its writing, editing and book-design—published a collection of essays by the “curious and eccentric” writer Gerald Murnane, a long-time resident of Melbourne. The seven books that he had published prior to this had all been works of fiction. The expression “curious and eccentric” I took from the blurb on the back of the book and, in fairness, whoever was responsible for writing the blurb is referring to Murnane’s imagination and not the man himself, but I don’t think it unreasonable to assume that if a man’s imagination is curious and eccentric then the rest of him probably is too.

The press like to depict the now [73]-years-old Murnane as “obsessive” and “eccentric,” focusing on his unusual habits: collecting marbles, studying Hungarian (although he has never left Australia) and maintaining a vast archive of his private writing and artwork. But precisely this obsessive quality gives his work its thematic unity.[1]

I am as guilty of that as anyone—they’re far too interesting not to mention—and you will find references to them in my three earlier articles on him: The Plains, Inland: common ground between Gerald Murnane and Samuel Beckett and Tamarisk Row (listing them in the order in which they were written) and I cannot promise that I won’t mention them in this article because Murnane himself talks extensively about them in one of the essays in this collection, but I hope to take care when I reach that point that these quirks don’t overshadow everything else in this book as they easily might.

Within this book Murnane, himself, refers to his “wandering, eccentric father” and so it’s probably not unreasonable that his son would demonstrate a propensity towards eccentricity sometime in his life. As it happens it manifested early on, but more on that later.

Eccentricity is one of those terms that people often use without always fully appreciating what it means and there is a slightly-disparaging edge to the expression; people snigger at eccentrics. The English have a long history of producing eccentrics; we Scots not so much. It’s a term that you really need to understand before we proceed so forgive me for dwelling on it. According to Wikipedia:

Eccentricity is often associated with genius, intellectual giftedness, or creativity. The individual's eccentric behaviour is perceived to be the outward expression of their unique intelligence or creative impulse. In this vein, the eccentric's habits are incomprehensible not because they are illogical or the result of madness, but because they stem from a mind so original that it cannot be conformed to societal norms. [italics mine]

Conventional Gerald Murnane is not, nor does he wish to conform to a general perception of what people regard as normal. ‘Normal’ changes all the time anyway. 96.7 percent of American households currently own television sets, the figure having plummeted from 98.9 percent previously. How long, however, will it be before people with old-fashioned TVs are regarded as eccentrics when everyone else has gravitated to watching everything online? Needless to say Murnane is one of the 1% of Australians who don’t own a TV. Is that eccentricity or simply a lifestyle choice?

Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs is a book comprising thirteen essays, all previously published in literary journals such as Age Monthly Review, Meanjin and Tirra Lirra between the years 1984 and 2003; they are arranged chronologically; two are edited transcripts of talks. They are all stand-alone pieces, nevertheless, viewed as a whole, they present a fascinating insight of what it means to Murnane to be a writer. There are other books by writers out there looking at their craft and if you’re a newbie seeking insight this is most certainly not the one you should tackle first, second or even third unless you find yourself writing stuff that doesn’t seem to fit in anywhere and yet you can’t give it up no matter how non-commercial you realise it is. If that’s the case, read on.

This is a long article even by my standards—not exactly a review—but I spend a little time on each essay talking about what jumped out at me.

Meetings with Adam Lindsay Gordon (1984)

![ALGordon ALGordon]() This is the first essay in the book.

This is the first essay in the book.

Adam Lindsay Gordon was a 19th century Australian poet, jockey and politician. He was actually born on Faial Island which is a Portuguese island of the Central Group of the Azores, but he moved to Australia when he was twenty, after receiving an English education, and remained there to the end of his life. He was the first to capture Australia and her people in the words of poetry. But he was also a bit of an eccentric. This is what his friend William Trainor had to say about him:

Oh, Gordon was, I think, the noblest fellow who ever lived! Very queer in his ways, though. I have ridden ten miles with him at walking pace, and he didn't say a word the whole time, but went on mumbling to himself, making up rhymes in his head.

As Gordon died in 1870 and Murnane was not born until 1939 the meetings he refers to are metaphorical. His first ‘meeting’ was in 1946 which would make him about seven years old. He gets to see Gordon’s house with his father while waiting on a bus during a holiday trip. For some reason he thinks the poet who once lived there was Robert Burns whose poetry he has already been exposed to “and found, of course, unreadable.” What is interesting to me is how this young boy views this house:

I recall my childish sadness that day for things lost or detained far from their rightful surroundings. I imagined that the house itself had been shipped many years before from Britain. Hearing that a man had composed poetry behind the locked doors, I thought of the poet as a sort of prisoner there, writing to pass the months or years of his sentence or exile.

Doubtless his seven-year-old self did not express his thoughts as succinctly as the man who wrote this in his forties but it gives us an early glimpse into the thought processes of this writer. Twenty years later when looking at a photograph of the house he realises something he had not back then, that this house was uncannily similar to “the house where [he] had spent the Bendigo years of [his] childhood” and which form the basis for his first published work of fiction, Tamarisk Row. The house front, identical to most others in the vicinity, reminded him of a face: “a pair of eyes and a nose under a frowning forehead” but I’m more interested to see what this symbolised to the young Murnane:

Those were the eyes of all the people detained where nothing could ever be a subject for poetry or fiction.

He could have been one “of those blankly staring people” had it not been for his father who introduced him, his imagination first and then the boy himself, to the plains that have become a fixture throughout his work.

Gordon crops up a number of times over the years. He is after all regarded as “Australia's acclaimed national poet”—at least that’s how his website introduces him. Murnane is not so sure. What he’s really looking at in this essay is what it means to be an Australian writer. Does one have to have been born there? Perhaps not. It is more to do with one’s attitude towards Australia. Gordon saw Australia “clearly enough for his purposes” but the problem for Murnane is that he sees Gordon as “a poet in the landscape and not a poet of the landscape.” Does this mean that Murnane is holding himself as an—or even the—Australian archetypal writer. Strangely enough, no:

[W]hen I tried to think of myself as a poet of the Australian landscape, I had to imagine as the place where my words came to me the library of a large homestead with windows overhung by English trees.

Gordon had every right to feel a little “homesick for England” but Murnane was born in Australia and has never left. The fact is that although to the world refers to him as an Australian writer that isn’t how he sees himself. This is something that becomes clearer as the essays progress. The nature of Murnane’s Australianness is taken up in Paul Genoni’s article The Global Reception of Post-national Literary Fiction: The Case of Gerald Murnane.

On the Road to Bendigo: Kerouac’s Australian Life (1986)

It is generally assumed that all great writers are, and have been since childhood, voracious readers, that the written word is the thing that had been the greatest influence on them and although Murnane did read as a child he was also a twentieth century child and so was to be influenced every bit as much, if not more so, by visual images although not the cinematic. Unlike a young Woody Allen (four years older than him) Murnane didn’t spend his childhood in the local picture palace nor was he like a young Beckett who “never missed a film starring

Charlie Chaplin,

Laurel and Hardy… or

Harold Lloyd.”

[2] Murnane says:

I watched perhaps twenty double-feature programs from 1946 to 1948. The films were mostly cowboy films, in black and white, and I watched them on Saturday afternoons in the Lyric Theatre, Bendigo, of which I remember only that the floor was quite level, so that the screen always seemed high above me and remote.

Why so few? He explains:

The films I watched made me discontented. Scene after scene disappeared from the screen before I had properly appreciated it; the characters moved and spoke much too fast.

Most people assume that writers are life’s great observers, hoovering up images—everything is fodder, nothing is sacrosanct—but I have to say that in many respects I am one of the least observant people you could ever meet and so, although I don’t understand why Murnane was not captivated by the silver screen as I have been ever since I saw the Disney film The Legend of Lobo back in 1962, I do get his explanation of what the problem was:

What I looked for in films was what I called pure scenery. I thought of pure scenery as the places safely behind the action: the places where nothing seemed to happen. – italics mine

This is why I struggle to find a correlation between someone who is a reader and someone who is a writer. When you read a book you are straight jacketed into a universe created by someone else. He or she tells you only what interests them. Murnane tries to explain how he wanted to respond when he saw a “banal arrangement of grassy middle-distance and hilly background”:

I tried to do to it something for which the simplest word I could have found was swallow. I wanted to feel that waving grass and that line of hills somewhere inside me.

[…]

I was not so literal-minded that I was troubled by cartoon images of a greedy boy with his cheeks swollen by a segment of landscape-pie. Yet the word swallow was not inapt. Getting the scenery from outside to inside seemed to engage me in some kind of bodily effort.

The nearest I can come to understanding the physicality of what he is talking about is opening my eyes wider to ensure that I absorbed as much of the image before me but since my writing is not image-centric I can’t pretend to fully grasp what he is talking about. I do, however, hone in on what interests me: moments, aspects, snippets. It is as if I’m tuned into a very narrow band and only what drifts into that wavelength is of any interest to me. Clearly Murnane was much the same. But why was he attracted to the scenery?

I had first been attracted to my scenery because nothing seemed to happen there; my grasses and hills were never the site of the frantic action that took place in the foreground of films. But when I was tired of waiting to understand my empty spaces, I allowed certain things to happen there. My scenery became the setting for most of my imagined adult life.

By 1960, when he would have been twenty-one, he “thought he was running out of space.” Not unusual. It happened to me a little earlier than that but every generation gets that bit more impatient than the one that preceded it. I imagine most eight-year-olds have gone through that kind of existential crisis these days. Looking back Murnane writes:

I wanted to be someone other than I seemed to be, and I thought I had first to surround myself with a new space. Writing this today, I see that what I needed was imagined space and not, as I thought then, actual space.

Fortuitously this was when Murnane first encountered On the Road and has what I’m going to call—not that I can recall that he ever has—an epiphany:

The book was like a blow to the head that wipes out all memory of the recent past. For six months after I first read it I could hardly remember the person I had been beforehand.

For six months I believed I had all the space I needed. My own personal space, a fit setting for whatever I wanted to do, was all around me wherever I looked. The only catch—by no means an unpleasant catch, I thought at the time—was that other people considered my space theirs too: my space coincided at last with the place that was called the real world. But the world was much wider than most people suspected. I saw this because I saw as the author of On the Road saw. Other people saw the same streets of the same Melbourne that had always surrounded them. I saw the surfaces of those streets cracking open and broad avenues rising to view.

Over the years, having read every new biography that was published on Kerouac, Murnane has come to realise that there are some surprising similarities between him and Kerouac, the most obvious being a love of horse racing; both boys invented their own racing games involving marbles, a central image in Murnane’s first work of fiction, Tamarisk Row.

Why I Write What I Write (1986)

Despite the title to the essay, the question he answers in the opening paragraphs is how he writes:

I write sentences. I write first one sentence, then another sentence. I write sentence after sentence.

I write a hundred or more sentences each week and a few thousand sentences a year.

After I’ve written each sentence I read it aloud. I listen to the sound of the sentence, and I don’t begin to write the next sentence unless I’m absolutely satisfied with the sound of the sentence I’m listening to.

When I’ve written a paragraph I read it aloud to learn whether all the sentences that sounded well on their own sound well together.

[…]

What am I listening for when I read aloud?

The answer is not simple. I might start with a phrase from the American critic Hugh Kenner…the shape of meaning. Writing about William Carlos Williams, Kenner suggested that some sentences have a shape that fits their meaning while other sentences do not.

![PatrickKavanagh PatrickKavanagh]() He goes on to list what others have had to say about what a sentence may or may not be, but the core of what he himself is looking for seems best summed up by the Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh who once said: “This is genius—a man being simply and sincerely himself.”

He goes on to list what others have had to say about what a sentence may or may not be, but the core of what he himself is looking for seems best summed up by the Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh who once said: “This is genius—a man being simply and sincerely himself.”

He never really gets round to answering the question posed at the start of this essay. He only asks it ten lines before it closes but the key line for me in this entire, albeit short, essay is this:

Writing never explains anything for me—it only shows me how stupendously complicated everything is.

Some Books are to be Dropped into Wells, Others into Fish Ponds (1987)

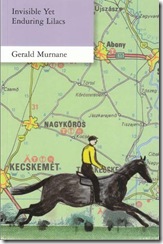

Why do we read? Before I sat down just now I picked up the TV & Satellite Week that sits beside my chair to make sure there was nothing on that I might want to record. I couldn’t tell you now, five minutes later, what is on, just that there is nothing on that I need to set the machine to watch. When I was about twenty—at least that would be my best guess because I don’t keep the kind of meticulous records that Murnane does—I bought a copy of Don Quixote (in John Menzies in East Kilbride; that I do remember) and read the first volume; the second I started but lost interest in. I can remember nothing about the book bar the famous windmill scene and that only vaguely. About nine years earlier, in 1970, Murnane had also read the book but by the time he came to write this essay, all he had to say about it as he stood staring at its spine was:

I could remember nothing of the book itself or of the experience of reading it. I could remember no phrase, no sentence; I could not remember one moment from all the hours when I had sat with that bulky book open in front of me.

![Don Quixote Don Quixote]() Ditto to all that. After some straining he thinks he recalls “a silhouette of a man on horseback” but then realised it was actually “a memory of Daumier’s painting of Don Quixote that had hung on the wall” in his office. I remember it because it was the image used on the cover of the paperback.

Ditto to all that. After some straining he thinks he recalls “a silhouette of a man on horseback” but then realised it was actually “a memory of Daumier’s painting of Don Quixote that had hung on the wall” in his office. I remember it because it was the image used on the cover of the paperback.

He gives up struggling to dredge up any memories concerning Don Quixote and decides to perform the same test on some other books:

From a sample of twelve—all of them read before 1976 and never opened since—I found seven that brought nothing to mind. If this was a fair sample, then of all the books that I had read once and had not read again, more than half had been wholly forgotten within a few years.

This, understandably, appalled him especially as from about 1960 to about 1990 he read more than a thousand books—he has a ledger where the titles and authors of all those books are recorded. And yet there were other books that he had not read for some thirty years that had left him with images that he sees nearly every day and not all of which are comforting. He illustrates by referencing the book Man-Shy by Frank Dalby Davison which he read when he was eight; the image is of a red cow dying of thirst and he has a good stab at recalling some of the actual text. He does better with Moby Dick but from there goes on to demonstrate how the images in Man-Shy and Moby Dick incorporate themselves into the landscape, the “pure scenery” in his head.

The Cursing of Ivan Veliki (1988)

Another short essay, a mere five pages long. Herein we get to meet the fourteen-year-old Gerald Murnane who thought he was a poet. The creation of Ivan Veliki is one that will make more sense to most writers than Murnane’s talk about “true fiction” or “pure scenery”. He sees the word ‘Veliki’ in a racebook—it was actually the name of a mare—but he imagines “a young man striding through tall grass. Ivan Veliki was the son of a lesser chieftain in one of the settled districts of the steppes” and he plans an epic poem featuring him. He composes the opening line as he “was walking north-west along Haughton Road toward the railway station then named East Oakleigh but now named Huntingdale. The time was early afternoon, the season was spring, and the year was 1953. […] I thought I had become a poet,” he says.

Murnane is not a poet now. I have no doubt that, like me, he has kept all his juvenilia, but although he spent the next ten years writing, or at least trying to write, poems he never became a poet. So why did he think he was a poet?

I thought at that time and for ten years afterwards that a poet was someone who saw in his or her mind strange sights and who then found words to describe those sights. The strange sights were of value because they brought on strange feelings—first in the poet and later in the person reading the poem. The faculty that enabled the poet to see strange sights was the imagination. Ordinary persons—non-poets—lacked imagination and saw only what their eyes showed them. Poets saw beyond ordinary things. Poets swathe virgin lands beyond the settled districts.

![]() It is interesting to compare this to his last book of fiction, Barley Patch, in which the narrator tells us that “fiction is the art of suggestion” and that “a person without imagination might still succeed in writing fiction as long as his or her reader is able to imagine.” He writes in that book that he had “come to understand that [he] had never created any character or imagined any plot.” The simplest way he found “of summing up [his] deficiencies was to say simply that [he] had no imagination.”

It is interesting to compare this to his last book of fiction, Barley Patch, in which the narrator tells us that “fiction is the art of suggestion” and that “a person without imagination might still succeed in writing fiction as long as his or her reader is able to imagine.” He writes in that book that he had “come to understand that [he] had never created any character or imagined any plot.” The simplest way he found “of summing up [his] deficiencies was to say simply that [he] had no imagination.”

Perhaps this is why the few poems he did write—a mere thirty in those ten years—irritated him when he read them. He was now in the position of the reader and yet no line of his poetry conjured up anything more than what he had seen. He gave up trying to be a poet and decided to write a novel. He thought of himself as “a failed poet who had turned to prose because it was easier to write.”

There is a long and not especially illustrious relationship between alcohol and writers. I’ve written about it but I’ve never used drink myself to aid or enhance my writing and I can only think of two lines written by me under the influence of alcohol that were any good at all. I’m not sure if Murnane’s approach is unique but I’ll let him tell it his way:

Each night before I wrote, I drank beer for two hours. While I wrote, I sipped whisky and ice-water. I hoped that the alcohol would blind me to the places that I did not want to write about and would allow my other organ of sight—my imagination—to operate.

It didn’t work. He gave up writing the novel and was unsuccessful in any further attempts at writing novels or short stories or at least he felt he was because when he discovered he was no longer using his imagination but simply writing about what he had seen, he quit. (Of course when Murnane uses the word ‘seen’ here he’s talking about what he sees in his mind but we will get to that.)

Birds of the Puszta (1988)

![]() In the first essay in this book we saw the kind of world that the young Murnane was brought up in; perhaps not suburbia but certainly suburban and yet one of the constant themes in his works of fiction are “the plains.” In this essay we learn, or at least he tries to explain, about, “the quality of the plains.” He describes “one of the chief events of [his] childhood,” the discovery of a nest containing eggs belonging to a pipit, Anhus australis, not up on a branch out of reach like “the secrets kept from the eyes of children” but right there amidst the grasses. He doesn’t touch it; he doesn’t dare to touch it because, as he puts it, “I would have seemed to myself to be offering an insult not just to the parent-birds but to something that I can only call the quality of the plains." He tries to explain:

In the first essay in this book we saw the kind of world that the young Murnane was brought up in; perhaps not suburbia but certainly suburban and yet one of the constant themes in his works of fiction are “the plains.” In this essay we learn, or at least he tries to explain, about, “the quality of the plains.” He describes “one of the chief events of [his] childhood,” the discovery of a nest containing eggs belonging to a pipit, Anhus australis, not up on a branch out of reach like “the secrets kept from the eyes of children” but right there amidst the grasses. He doesn’t touch it; he doesn’t dare to touch it because, as he puts it, “I would have seemed to myself to be offering an insult not just to the parent-birds but to something that I can only call the quality of the plains." He tries to explain:

Plains looked simple but were not so. The grass leaning in the wind was all that could be seen of plains, but under the grass were insects and spiders and frogs and snakes—and ground-dwelling birds. I thought of plains whenever I wanted to think of something unremarkable at first sight but concealing much of meaning. And yet plains deserved, perhaps, not to be inspected closely.

The notion of plains is discussed at some length in his book of the same name but I would recommend you take the time to read Karin Hansson’s paper, Gerald Murnane's Changing Geographies from which the following quote comes:

The traveller in The Plains, for instance, finds himself in an enclave, “encircled by Australia” (P 6), that is space surrounded by place, “a zone of mystery enclosed by the known and the all-too-accessible” (P 77).

Then as the exploration proceeds, a number of seemingly unrelated geographical key concepts are introduced and the setting becomes increasingly imprecise, “the world itself…one more in an endless series of plains” (P 9). Motifs of space, territory and landscape are related to notions of identity and the very act of writing:

[The plains] are not … a vast theatre that adds significance to the events enacted within it. Nor are they an immense field for explorers of every kind. They are simply a convenient source of metaphors for those who know that men invent their own meanings. (P 92)

Pure Ice (1988)

Where do you get your ideas from? It’s a question that most writers will have been asked often in so many words. In some cases I could tell you and you would see the connection but whenever I’ve read Murnane describe the central image, the fulcrum on which his books rest, it is not always easy to see how the book emanated from that imagine. In the earlier essay, ‘Some Books are to be Dropped into Wells, Others into Fish Ponds’ he wrote:

It was a strange experience to discover, halfway through writing what I thought was a story about X, that I had really been writing the story of Y. I had thought for three years that I was writing a book whose central image was a patch of soil and grass, but one day in January 1987 I learned that the central image of my book was a fish pond.

![]() The book was Inland which I have read and reviewed. The book does talk about “grasslands between the Moonee Ponds and the Merri” but I can’t honestly say that that image jumped out at me as the central image. In this short essay we discover what prompted the writing of the book. It was an image—it’s always going to be an image with Murnane—which he encountered whilst reading Peoples of the Puszta, a girl running out into the snow and being in such a rush to do so that she forgets her boots; this, of course, gets mixed up with his own experience of seeing snow for the first time “falling faintly on [a] schoolground for a few minutes in 1951.” Being aware of these things now makes me curious to read Inland again to see if I can understand his creative process but I'm not sure I need to; I'm content with the end result.

The book was Inland which I have read and reviewed. The book does talk about “grasslands between the Moonee Ponds and the Merri” but I can’t honestly say that that image jumped out at me as the central image. In this short essay we discover what prompted the writing of the book. It was an image—it’s always going to be an image with Murnane—which he encountered whilst reading Peoples of the Puszta, a girl running out into the snow and being in such a rush to do so that she forgets her boots; this, of course, gets mixed up with his own experience of seeing snow for the first time “falling faintly on [a] schoolground for a few minutes in 1951.” Being aware of these things now makes me curious to read Inland again to see if I can understand his creative process but I'm not sure I need to; I'm content with the end result.

The Typescript Stops Here or: Who Does the Consultant Consult? (1989)

Here Murnane talks about some of the other jobs he has done to support himself. One of these was as a fiction consultant—as opposed to a fiction editor—for the literary magazine Meanjin. During the year 1988 the magazine received some 700 pieces of fiction all of which were read first by the editor and many also by the assistant editor; about one hundred of these were passed onto Murnane for his seal of approval. He gripes a bit about the title ‘consultant’ since he himself consults no one—ignoring the fact that he is actually the one being consulted—and then proceeds to talk about how he goes about the process of selection by himself ‘consulting’ his “better self.” As with other expressions he had co-opted to suit his own ends he has to explain what he means:

Readers of goodwill will understand me when I write that my better self is the part of me that writes fiction in order to learn the meaning of the images in my mind. The same readers will understand me when I write that my better self is the part of me that reads fiction in order to learn the meanings of the images in other minds.

He reads much as he writes, one sentence at a time, and his main criticisms of the hundred-odd stories that he read in 1988 were that the sentences were shoddy:

[They were] sentences that seemed to have been dashed down and never read aloud, let alone revised, sentences seemingly unconnected with human thoughts or feelings. Stories by previously unpublished writers most commonly made me suspect that the writers were nervous—that they had not yet learnt the value of their own memories and dreams and thoughts and feelings as material for fiction.

![Singer Singer]() Perhaps the best advice he finds he can give, however, is not his own. It belongs to Isaac Bashevis Singer:

Perhaps the best advice he finds he can give, however, is not his own. It belongs to Isaac Bashevis Singer:

Before I write a story, I must have a conviction that it is a story that only I can write.

If that is the litmus test Murnane would use certainly I cannot imagine anyone else writing books like him.

Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs (1990)

That Proust would be a writer that Murnane would connect with comes as no surprise to me. Beckett certainly was impressed by him and I do see some similarities between the three writers. Proust suggests, in In Search of Lost Time, that in reality, as soon as each hour of one's life has died, it embodies itself in some material object and hides there. (The scene concerning the madeleine is well-known even to those who know nothing more about Proust.) There it remains captive forever unless we should happen on the object, recognise what lies within, call it by its name, and so set it free. As it turns out, Proust's original model may have been a piece of soggy toast. In an earlier draft, the narrator is offered a piece of "dry toast" which he dips in his tea and it is the "bit of sopped toast" that triggers the familiar surge of memory. Murnane, I think, would not have changed the trigger which could just as easily be a place, a marble he owned as a child (and likely still owns) or some racing colours. I’m not saying this is the single key to understand Murnane but it will unlock the great gates and let you into the grounds of his imaginary estate.

In this essay, with his usual raw (and comical) honesty, Murnane recalls both the first time he encountered Swann’s Way:

When I began to read the first pages of Proust’s fiction, I had just opened the first tin of sardines that I had bought—a product of Portugal—and had emptied the contents over two slices of dry bread. Being hungry and anxious not to waste anything that had cost me money, I ate all of this meal while I read from the book propped open in front of me.

For an hour after I had eaten my meal, I felt a growing but still bearable discomfort. But as I read on, my stomach became more and more offended by what I had forced into it.

Eventually he is overcome by nausea and for the next twenty years found that every time he handled that volume he would feel, in his mind at least, a mild flatulence.

Although I am sure the expression occurred in some, if not all, of the earlier essays this is the first one where another of Murnane’s stock expressions jumped out at me: “in my mind”. He addresses the matter later so just hold that thought in your minds for now.

![swann's way swann's way]() The rest of this essay charts the various connections that his mind has made emanating from this first reading of Swann’s Way jumping back to the forties (a photograph of him standing beside a sunlit wall), the fifties (a fly buzzing near a bush of tiger lilies), throughout the sixties (a “complex arrangement of vistas of green fairways”), into the seventies (another buzzing fly) right up until July 1989 when we find him writing the very text that we are reading. The sentences get more and more involved—Murnane has no problem with longer sentences—until, at the very end, it comes clear what he is trying to do here, to communicate the process by which he produces the kind of writing he does. It has the feel, however, of a translation. By that I mean although his English is perfect you—or at least I—feel that not everything is coming across in the translation. Murnane uses the phrase “in my mind” more and more as if by pure repetition alone we will understand what he is trying to get across.

The rest of this essay charts the various connections that his mind has made emanating from this first reading of Swann’s Way jumping back to the forties (a photograph of him standing beside a sunlit wall), the fifties (a fly buzzing near a bush of tiger lilies), throughout the sixties (a “complex arrangement of vistas of green fairways”), into the seventies (another buzzing fly) right up until July 1989 when we find him writing the very text that we are reading. The sentences get more and more involved—Murnane has no problem with longer sentences—until, at the very end, it comes clear what he is trying to do here, to communicate the process by which he produces the kind of writing he does. It has the feel, however, of a translation. By that I mean although his English is perfect you—or at least I—feel that not everything is coming across in the translation. Murnane uses the phrase “in my mind” more and more as if by pure repetition alone we will understand what he is trying to get across.

Stream System (1990)

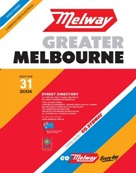

This is an edited version of a presentation to the staff and students of the English Department of La Trobe University which Murnane delivered on July 1st 1988. It’s not often that essays have twists in the tails but this one does and it is all to do with preconceptions. It’s a fairly long essay, thirty-one pages long, in which he talks about the slightly circuitous route he took from his home to the university, a route that took in two creeks, Salt Creek and Darebin Creek, which form a part of what the Melway Street ![Street Directory Street Directory]() Directory of Greater Melbourne refers to by the words STREAM SYSTEM.

Directory of Greater Melbourne refers to by the words STREAM SYSTEM.

This is a similar essay to the one that precedes it in the book, a wander through the mind of Gerald Murnane, and, like all the essays (and, indeed, all his works of fiction), we get interesting autobiographical details along the way. Here we encounter another of Murnane’s expressions, “true fiction.” So what’s “true fiction”? Creative non-fiction? Semiautobiographical fiction? In ‘The Typescript Stops Here’ he explains:

When I speak or write about what I call true fiction, some people think that I think of the best fiction as a sort of confessional writing. I deny this. What I call true fiction is fiction written by men and women not to tell the stories of their lives but to describe the images in their minds…

This is discussed at some length in David Pereira’s essay The Landscape of Gerald Murnane: The Fictions of Everyday Life. Writing, for Murnane, is very much a process of discovery, following a trail of images to see where they lead.

This essay concludes with the following:

If anyone were to ask me today what method I use for writing my fiction ... I would say that I write fiction by following the stream system.

The term is not defined but rather demonstrated in the preceding thirty pages.

Secret Writing (1992)

Up until four years ago I was a secret writer. I made no secret of the fact that I was a writer but for the most part I kept my writing to myself. I wrote novels and put them in binders and pretty much forgot about them. Many of you reading this will have similarly-filled drawers, hard drives or binders. Only not so much these days because these days publication is easy, so inexpensive that anyone can just go ahead and do it themselves. Back in 1962 in Australia it was a different world as Murnane relates in this essay:

If I were a young writer starting out in 1992, I would sometimes be tempted to despair when I thought of how many other writers are already being published. In 1962, what tempted me sometimes to despair was the thought of how few Australians seemed to be writing fiction or getting it published. I felt in 1962 that writing fiction was almost an un-Australian thing to be doing.

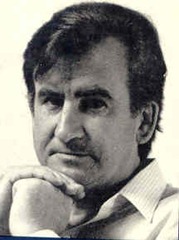

![gerard murnane gerard murnane]() And yet he finds he cannot help himself but finding no one within his profession (he was a primary school teacher at the time) with whom he cared to discuss his writing—not that he has ever been terribly keen to talk about it—he did his writing on Sundays and on three or four evenings each week and kept what he was doing pretty much to himself for the next ten years until he thought he had something publishable—can you imagine anyone today waiting ten years before trying to get published or doing it themselves?—and from then on his name was out there and he was no longer a secret writer something that, at times, he regrets because of the attention that followed:

And yet he finds he cannot help himself but finding no one within his profession (he was a primary school teacher at the time) with whom he cared to discuss his writing—not that he has ever been terribly keen to talk about it—he did his writing on Sundays and on three or four evenings each week and kept what he was doing pretty much to himself for the next ten years until he thought he had something publishable—can you imagine anyone today waiting ten years before trying to get published or doing it themselves?—and from then on his name was out there and he was no longer a secret writer something that, at times, he regrets because of the attention that followed:

During the years of my secret writing, nobody ever asked me to look at their own writing and to comment on it. During those years, no editor of a magazine approached me at a party and asked me to write a piece for her magazine.

I would like my next book to be published with a pseudonym on the cover. Better still, I would like the book to be published with no author’s name on it. But I would like more than that. I would like all books of fiction to be published without their author’s names. I would like all writers to be secret writers. Then readers would read books with more discernment. I believe many readers are too much influenced by the names on the fronts of books.

He then cites an instance where, at a seminar, he handed around photocopies of a typed page of prose and asked the editors to correct any errors of which there were many. He then revealed that he had copied the page from a recent prize-winning novel by one of Australia’s best known writers of fiction and had just altered the names of persons and places. I can only imagine what he would have to say today, twenty years down the road.

The Breathing Author (2002)

“I have for long believed,” writes Murnane, at the beginning of this essay, “that a person reveals at least as much when he reports what he cannot do or has never done as when he reports what he has done or wants to do.” It is a fair enough statement. For my part I think that spending too much time dwelling on such matters can contribute to a skewed view of the person under the microscope. So he doesn’t watch TV; so he’s never been in an aeroplane; so he’s spent his entire life in a small corner of Australia; so he doesn’t understand exchange rates or the workings of the International Date Line and has never been to the opera. Okay, I admit I find it strange that someone having grown up in as sunny a place as I’ve always assumed Australia to be has never worn sunglasses but I bet there are loads of people who have never voluntarily gone into an art gallery or a museum. That he has never engaged fully with many of the appliances that so many of us take for granted is not so surprising. Had I never worked in an office I would have seen no good reason to learn how to operate a fax and I have no particular interest in mobile phones; I have one but I could as easily do without one for all it gets used. When he wrote this essay he had never used a computer. Not so strange in 2002 and now I’m told he has given in and bought one although the World Wide Web is still something of a mystery to him.

I could go on. One thing I would like to quote is this, however:

I have read hurriedly Terry Eagleton’s book Literary Theory: An Introduction, Blackwell 1983. I have read much less hurriedly Wayne C. Booth’s book The Rhetoric of Fiction University of Chicago Press. … I do not recall having read any other book on literary theory or related subjects.

![Rhetoric of Fiction Rhetoric of Fiction]() It is in Booth’s book he encountered the expression “the Breathing Author” or, elsewhere in the text, “the Flesh-and-Blood Author.”

It is in Booth’s book he encountered the expression “the Breathing Author” or, elsewhere in the text, “the Flesh-and-Blood Author.”

This essay doesn’t simply provide us with a list of his personal idiosyncrasies. We learn more about the things that do stimulate and engage him, things like charts and diagrams, which he has used frequently to help him plan most of his book-length pieces of fiction even if, ultimately, he could never get his fiction to conform to the shape he had planned for it. I bet the list of authors out there who find their books go in directions they had not planned or conceived is a long one indeed.

Again he makes an attempt to describe how he writes and notes that his explanation might come across as “niggardly”—one might almost think he’s being facetious in his explanation which reminds me of something Stephen King is reported to have said: "When asked: How do you write? I invariably answer: One word at a time."I don’t think he’s being facetious either, incidentally. Murnane is, typically, a bit wordier in his explanation but essentially that’s what he’s saying. He thinks of himself as “a technical writer [and the] task of this sort of writer,” he says, “is to report in the plainest language the images that most claim his attention from among the images in his mind and then to arrange his sentences and paragraphs (and, if applicable, his chapters) so as to suggest the connections between those images.”

In the previous essays there have been numerous instances of images that have stood out in some way for Murnane. Typically he has co-opted a word to try and help others grasp the process that’s in play here; he calls it winking. Image after image passes in front of his mind’s eye and then one winks at him. In what way winks?

I choose deliberately the word winking to describe this primitive signal to me from some patch of colour or some shape in my mind. I so choose because my seeing the signal never fails to make me feel reassured and encouraged as many a person must feel after being winked at by another person. And I choose the word winking in this context because a wink from one person to another often signals that the two persons share a secret knowledge, so to speak…

I think most of us would describe what’s going on here as inspiration. Where, I think, he might differentiate between being winked at and being inspired by is that the winking is a purely internal thing, taking place within his internal landscape, his mind. The only time he uses the word ‘inspiration’ in this book is with reference to something a philosopher once wrote—unusually he has forgotten who—from whom he drew what he calls “a sort of inspiration as a writer of fiction. That statement was to the effect that everything exists in a state of potentiality; that is to say, anything can be said to have a possible existence.”

The Angel’s Son: Why I Learned Hungarian Late in Life (2003)

During his life Murnane has become competent, to varying extents, in six languages (Maltese, Latin, French, English, Arabic and Hungarian) although, unlike Beckett, he has been content to write his fiction in English. He learned Hungarian in order to read the book I mentioned earlier, Puszták Népe [People of the Plains], which he had read in translation, in the original language. Although that’s not really the reason. It goes deeper than that and it all boils down to an image he saw, or imagined (he is no longer sure), of “a certain dark-haired young woman” who has ![Teach Yourself Hungarian Teach Yourself Hungarian]() often appeared in his mind since that time, 1956, when he read in the newspapers about and, more importantly, “pored over … photographic images of the Hungarian Revolution.” He knew, and realised he would never know, even the girl’s name, let alone any of her history. The only thing he felt he could do for her was to learn her language.

often appeared in his mind since that time, 1956, when he read in the newspapers about and, more importantly, “pored over … photographic images of the Hungarian Revolution.” He knew, and realised he would never know, even the girl’s name, let alone any of her history. The only thing he felt he could do for her was to learn her language.

You might wonder why he didn’t arm himself with “a teach-yourself guide book with an accompanying cassette” at that time. Well, apart from the fact that cassettes didn’t go into general distribution until the early sixties, it was because this is Murnane we’re talking about here. He has a long (a very long) gestation period, as he says in ‘Some Books are to be Dropped in Wells’ about the writing of Inland, “[H]ow could I have lived for more than thirty years without realising how full of meaning my fish pond was?” And yet in this essay we see that the reading of People of the Plains, which he first read in 1977, was another important component in the creation of this text.

***

Needless to say there is a lot I have not discussed or even mentioned that is covered in this book. To do so I would have needed to write a text every bit as long as the one he has written, probably longer. I have tried to look for a theme weaving its way through the texts even though each is a standalone piece of writing. I have now read five books by Murnane: The Plains, Inland, Barley Patch, Tamarisk Row and this collection of essays. There is much overlap and yet I feel I’m still a long way away from understanding the man. Not that I think that any of us can come close to understanding the mind of another purely by reading words on a page. What comes across in these essays, though, is a genuine desire to communicate the incommunicable.

I have never taken a creative writing class. I don’t pooh-pooh them but I don’t think they’re for me. They clearly weren’t for Murnane. And they may not be for you. I don’t know if Murnane ever read Bukowski. If he was drawn to Kerouac I might imagine that he might have been curious about his peers; anyway, I think, even if he hadn’t read it before, he might connect with Bukowski’s poem ‘So You Want To Be A Writer’which ends:

when it is truly time,

and if you have been chosen,

it will do it by

itself and it will keep on doing it

until you die or it dies in you.

there is no other way.

and there never was.

REFERENCES

[1] James Halford, ‘Fiction: Tamarisk Row by Gerald Murnane’, M/C—Media and Culture

[2] Deirdre Bair, Samuel Beckett: A Biography,p.48

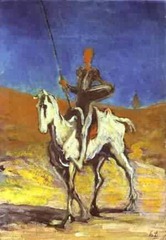

He heads west. With the hare in his pocket. He doesn’t have especially large pockets; it’s just a very young hare. In time he comes to a village where he buys some cigarettes and a lemonade from a red kiosk. The girl asks him if he’s a criminal because he came out of the forest. He says no and then “Vatanen took the hare out of his pocket and let it bumble around on the bench,” and any issues the girl might have had vanished: “Hey, a bunny!” This sets a pattern that is repeated again and again throughout the book. Any guy who is happy to wander around with a hare like this can’t be a bad guy. The girl directs him to the local vet who bandages the hare’s paw and instructs Vatanen how to care for the creature. The two of them stay there for several pleasant days, the hare getting tamer and tamer all the time.

He heads west. With the hare in his pocket. He doesn’t have especially large pockets; it’s just a very young hare. In time he comes to a village where he buys some cigarettes and a lemonade from a red kiosk. The girl asks him if he’s a criminal because he came out of the forest. He says no and then “Vatanen took the hare out of his pocket and let it bumble around on the bench,” and any issues the girl might have had vanished: “Hey, a bunny!” This sets a pattern that is repeated again and again throughout the book. Any guy who is happy to wander around with a hare like this can’t be a bad guy. The girl directs him to the local vet who bandages the hare’s paw and instructs Vatanen how to care for the creature. The two of them stay there for several pleasant days, the hare getting tamer and tamer all the time. constructing an enclosure for reindeer” north of the Arctic Circle. All goes well – he’s content, the hare is content – until the appearance of the bear. And then we get to see a different side to Vatanen. Up until this point you might be forgiven for thinking that he was only really interested in running away but suddenly we see him in hot pursuit – and, no, before you think the worst of the poor bear, it’s not gone and killed the hare – but how things are going to end is a mystery. Actually that’s true. How the book ends is a mystery and I’m not going to spoil it by telling you but I didn’t see it coming. The Finnish film copes well with its magicalness; the French one not so much.

constructing an enclosure for reindeer” north of the Arctic Circle. All goes well – he’s content, the hare is content – until the appearance of the bear. And then we get to see a different side to Vatanen. Up until this point you might be forgiven for thinking that he was only really interested in running away but suddenly we see him in hot pursuit – and, no, before you think the worst of the poor bear, it’s not gone and killed the hare – but how things are going to end is a mystery. Actually that’s true. How the book ends is a mystery and I’m not going to spoil it by telling you but I didn’t see it coming. The Finnish film copes well with its magicalness; the French one not so much. Arto Paasilinna was born in Kittilä in Lapland on April 20th 1942. Paasilinna ("stone fortress" in Finnish) is a name invented by his father, who changed his from Gullstén, following a family conflict.

Arto Paasilinna was born in Kittilä in Lapland on April 20th 1942. Paasilinna ("stone fortress" in Finnish) is a name invented by his father, who changed his from Gullstén, following a family conflict.

It is interesting to compare this to his last book of fiction,

It is interesting to compare this to his last book of fiction,  In the first essay in this book we saw the kind of world that the young Murnane was brought up in; perhaps not suburbia but certainly suburban and yet one of the constant themes in his works of fiction are “the plains.” In this essay we learn, or at least he tries to explain, about, “the quality of the plains.” He describes “one of the chief events of [his] childhood,” the discovery of a nest containing eggs belonging to a

In the first essay in this book we saw the kind of world that the young Murnane was brought up in; perhaps not suburbia but certainly suburban and yet one of the constant themes in his works of fiction are “the plains.” In this essay we learn, or at least he tries to explain, about, “the quality of the plains.” He describes “one of the chief events of [his] childhood,” the discovery of a nest containing eggs belonging to a  The book was Inland which I have read and reviewed. The book does talk about “grasslands between the Moonee Ponds and the Merri” but I can’t honestly say that that image jumped out at me as the central image. In this short essay we discover what prompted the writing of the book. It was an image—it’s always going to be an image with Murnane—which he encountered whilst reading

The book was Inland which I have read and reviewed. The book does talk about “grasslands between the Moonee Ponds and the Merri” but I can’t honestly say that that image jumped out at me as the central image. In this short essay we discover what prompted the writing of the book. It was an image—it’s always going to be an image with Murnane—which he encountered whilst reading

Tim Love lives in Cambridge, England, having lived in Portsmouth, Norwich, Bristol, Oxford, Nottingham and Liverpool. He works as a computer programmer and teacher, and is married with two bilingual (Italian) children. His prose has appeared in Panurge, Dream Catcher, Journal of Microliterature, etc., and has won prizes run by short Fiction and Varsity. His poetry pamphlet Moving Parts was published by

Tim Love lives in Cambridge, England, having lived in Portsmouth, Norwich, Bristol, Oxford, Nottingham and Liverpool. He works as a computer programmer and teacher, and is married with two bilingual (Italian) children. His prose has appeared in Panurge, Dream Catcher, Journal of Microliterature, etc., and has won prizes run by short Fiction and Varsity. His poetry pamphlet Moving Parts was published by

![A Man's Hands Final_thumb[1] A Man's Hands Final_thumb[1]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-sE_TU4Y3gWs/UOwHe_SfzoI/AAAAAAAAGPM/wBZZbW3-hfU/A%252520Man%252527s%252520Hands%252520Final_thumb%25255B1%25255D_thumb%25255B1%25255D.png?imgmax=800)

Tania Hershman

Tania Hershman

When I wrote

When I wrote

MDMA

MDMA

Niccolò Ammaniti

Niccolò Ammaniti

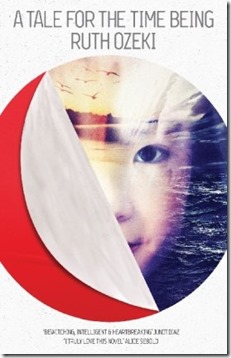

Ruth Ozeki

Ruth Ozeki