![The_attraction_of_emptiness The_attraction_of_emptiness]()

Silence, yes, but what silence! For it is all very fine to keep silence, but one has also to consider the kind of silence one keeps. – Samuel Beckett

I discovered the French poet Eugène Guillevic a while back when, on a whim, I decided I’d have a go at translating a poem from French into English. You can see how well I did here. The poem I picked was actually only an excerpt from a long poem entitled Art poétique, poème 1985-1986 although it really is a collection of about 160 short—occasionally tiny—poems all of which stand perfectly well on their own and yet are obviously connected to the surrounding material. The same is true of the book-length poem Carnac of which its translator Denise Levertov writes:

Guillevic has sustained a profound book-length poem, but formally his method in it remains the sequence of short poems, each paradoxically autonomous yet closely related to one another.

Since I couldn’t find an English translation of the section I’d picked online (although, oddly, there was one in Russian) I decided to buy the book and I’m glad I did because Guillevic (he dropped the Eugène in later life) was right down my street.

He was born on August 5th, 1907 in Carnac which is a commune beside the Gulf of Morbihan on the south coast of Brittany in the Morbihandepartment in north-western France and then, in 1909, moved to Jeumont on the Belgian border. Of course if you’re not familiar with France you probably imagine that everyone in France speaks French—a not unreasonable assumption—but in Carnac they speak Breton, a language more closely related to Cornish than French, and in Jeumont, although French dominates in that area, there are two significant minority languages, Dutch and Picard. Moving then to Alsace near the Swiss border the next language he had to become familiar with was Alsatian—a German dialect—so the fact is that this French poet didn’t actually hear conversational French spoken about him until he was twenty. This would be about the same age Beckett was (they were contemporaries) when he first moved to France to take up the post of lecteur d'anglais in the École Normale Supérieure in Paris; in fact they will have been neighbours for a time although I have no idea if they ever met. Beckett, of course, famously turned his back on English to write in French and, although also something of a polyglot himself, the fact is that French was not his native tongue. As Rolf Breuer notes:

It was a transformation from a witty satirist using all the resources of [Beckett’s] native English to a writer treating themes of intellectual poverty and impotence who turned to French as a means of conveying these subjects adequately.[1]

Their mature poetry has much in common. James Sallis writes:

Gradually over the years Guillevic developed a poetry of common speech, a poetry without artifice; he did not want to knit an alternative world from the warp and woof of language, but to ferret out what knowledge he could of the actual world, to find what identification he could with the world and things of the world, from among the baffles of self and of language.[2]

Of course, when I hear something like “poetry of common speech, without artifice”, that makes me think of the antipoetry of Nicanor Parra who exhibits a similar distaste for standard poetic pomp and function.

![guillevic1 guillevic1]() Guillevic is his own man though and I reference these others only to put him in perspective. You wouldn’t jump to call Beckett a poet of the landscape and yet landscape—especially that of his childhood—clearly informs his choices. He was at home wandering around the bleak hills surrounding Dublin as Guillevic was comfortable in the bare, fraught landscape of Brittany. (Even though he was only two when the family moved away from Carnac he retained an abiding love for the place. “Brittany acts as a centre of gravitation in his oeuvre.”[3]) Likewise they both have an abiding love and need of silence.

Guillevic is his own man though and I reference these others only to put him in perspective. You wouldn’t jump to call Beckett a poet of the landscape and yet landscape—especially that of his childhood—clearly informs his choices. He was at home wandering around the bleak hills surrounding Dublin as Guillevic was comfortable in the bare, fraught landscape of Brittany. (Even though he was only two when the family moved away from Carnac he retained an abiding love for the place. “Brittany acts as a centre of gravitation in his oeuvre.”[3]) Likewise they both have an abiding love and need of silence.

Comme certainties musiques

Le poème fait chanter le silence,

Amene jusqu’à toucher

Un autre silence,

Encore plus silence. | Like some music

The poem makes silence sing,

Leads us until we touch

Another silence,

Even more silence. |

from Art Poètique (pp.74,75)

This reminded me of something Charles Juliet said about Beckett:

Beckett tells Juliet that he often sat through whole days in silence in his cottage in Ussy-sur-Marne. With no paper before him, no intent to write, he took pleasure in following the course of the sun across the sky: "There is always something to listen to" he says. So Beckett didn't experience silence as silence: it was attention.[4]

Or as Guillevic might have put it:

I’m here

Doing nothing.

But maybe

I’m out hunting.

from Art Poètique (p.109)

Juliet forced himself to break the first silence by telling Beckett of how his appreciation of his work changed after reading Texts for Nothing: "what had impressed me most" he says "was the peculiar silence that reigns... a silence attainable only in the furthest reaches of the most extreme solitude, when the spirit has abandoned and forgotten everything and is no more than a receiver capturing the voice that murmurs within us when all else is silent. A peculiar silence, indeed, and one prolonged by the starkness of the language. A language devoid of rhetoric or literary allusions, never parasitized by the minimal stories required to develop what it has to say."

– Yes, he agrees in a low voice, when you listen to yourself, it's not literature you hear.[5]

Beckett’s late writing (not simply his poetry, of course) has this in common with Guillevic’s approach to poetry; a voluntary poverty:

Il te faut de la pauvreté

dans ton domaine. C'est comme ce besoin qu'on peut avoir

d'un mur blanchi à la chaux. Une richesse, une profusion

de mots, de phrases, d'idées t'empêcheraient de te centrer

d'aller, de rester là où tu veux

où tu dois aller pour ouvrir,

pour recueillir. Ta chambre intérieure

est un lieu de pauvreté. | You need some poverty

In your domain.

It’s like the need you can feel

For a whitewashed wall.

A wealth, a profusion

Of words, sentences, ideas

Would not let you be centred,

Or go, or stay

Wherever you want,

Wherever you have to go.

To open up,

To remain in silence.

Your inner chamber

Is a place of poverty. |

from Art Poètique (pp.60,61)

As Russell Smith writes regarding Beckett, “the wordlessness of the late theatre works, seem to enact a philosophy of linguistic nihilism, a repudiation not only of literary conventions but of language itself, a reaching towards the silence which would be its only true expression”[6] or, as Beckett himself puts it in Texts for Nothing X:

No, no souls, or bodies, or birth, or life or death, you've got to go on without any of that junk that's all dead with words, with excess of words, they can say nothing else, they say there is nothing else.

So once you’ve got rid of all the words or as many words as you can, what then? What is the point to all this silence?

Du silence

Je fore,

Je creuse.

Je fore

dans le silence

Ou plutôt

Dans du silence,

Celui qu'en moi

Je fais.

Et je fore, je creuse

Vers plus de silence,

Vers le grand,

Le total silence en ma vie

Où le monde, je l'espère,

Me révélera quelque chose de lui. | Silence

I drill,

I dig.

I drill

in the silence

or rather

in the silence

that is

within me.

And I drill, I dig

to more silence,

to the vast,

the total silence of my life

where its world, I hope,

will reveal something of myself. |

Possibles futures, p.165 (translation, me)

He uses similar terminology in another poem which opens:

S'il n'y avait

Qu a creuser dans le noir,

S'il n'y avait

Qu'à perforer

Pour arriver

Où la lumière elle-même.

where he talks about digging through the dark to get to the light, to literally perforate darkness. In his thesis on Guillevic Jaroslav Havir talks about this poem:

The two conditional phrases that open the text as an implied question that becomes a statement – "What if it were only a matter of digging and drilling?" "Creuser" and "perforer" suggest not only material work, but imply that strong obstacles and resistance have to be broken through by writing. Writing becomes a working through, a negative operation of breaking up of standing discourse – "effraction"[7]– to reach another discourse of revelation.[8]

![Geometries_Cover Geometries_Cover]() And yet in a poem from his second collection, Exécutoire (Geometries), Guillevic realises:

And yet in a poem from his second collection, Exécutoire (Geometries), Guillevic realises:

To see inside walls

Is not given us.

Break them as we will

Still they remain surface.

Is this not the problem with all poetry that no matter how far you dig (into yourself, if you’re the poet, or into the poem if you’re its reader) no poem ever completely reveals itself?

Although [Guillevic] has spoken of poetic creativity in terms of ‘jaillissement’[gushing], he also states that his poems are always thoroughly written and rewritten possibly many times over.[9]

This is clear when you start looking at translating one of these poems. On one level they are indeed the most straightforward of poems with very few words and mostly simple ones at that but John Montague discovered that he had his work cut out when he settled down to translate Carnac. He began his task with an “excess of enthusiasm”[10] but found out, much as I did when I took on what I thought was a straightforward poem about trickling sand from one hand to the other, just how hard it can be to deal with simple, direct language. It took “twenty years to bring this translation to heel.”[11]

Beckett’s French poetry has also proven to be a nightmare to translate. Some, thankfully, he did himself but there were many he chose to leave and let the rest of us struggle with. Here, for example, is a tiny offering, Google’s shot and my humble effort at translation:

écoute-les

s’ajouter

les mots

aux mots

sans mots

les pas

aux pas

un à

un | listen to the

add

words

the words

no words

not the

not to

one

a | listen

add words

to words

without words

not-one

to one

to not |

I could be—and probably am—way off here. But it sounds like something Beckett would have said, a progression from nothing to something and then back to a different kind of nothing. A recent attempt to translate one containing just seven words –

![Beckett Beckett]() rêve

rêve

sans fin

ni trêve

à rien

dream

without cease

nor ever

peace

from Mirlitonnades[12]

– spurred weeks of readers' attempts in the letters page of the Times Literary Supplement. Roger O'Keefe, for instance, rendered it:

dream

without cease

or treaty

of peace

What James Sallis writes about Guillevic can equally be applied to Beckett:

What is at the very heart of his work’s excellence—the simplicity of its diction, the unadorned language, its very modesty—renders it all but untranslatable. Even in French, Guillevic can be an elusive read. Slight, elliptical, gnomic, the poems vanish when looked at straight on. "Les mots / C’est pour savoir," he says. Words are for knowing. And by les mots he means, resolutely, French words. Because their mystery, their magic, is in the language itself, these poems do not easily give up their secrets, or travel well. They are their secrets. They crack open the dull rock of French and find crystal within. In English, all too often, only the dullness, the flatness, remains.[13]

Beckett’s last poem is well known. It opens:

folly –

folly for to –

for to –

what is the word –

folly from this –

all this –

folly from all this –

given –

folly given all this –

seeing –

folly seeing all this –

this –

what is the word –

from ‘What Is The Word’ (Beckett’s own translation of ‘Comment Dire’)

Some have wondered why he chose to translate folie as folly. It seemed obvious to me and yet on investigation it turns out that the common translation of folie into English is actually ‘madness’. My own thought is that he is using ‘folly’ to suggest both foolishness and also to make us think about an actual folly, a whimsical or extravagant structure built to serve as a conversation piece. He specifically mentions a folly in his play That Time:

A — Foley was it Foley’s Folly bit of a tower still standing all the rest rubble and nettles where did you sleep no friend all the homes gone was it that kip on the front where you no she was with you then still with you then just the one night in any case off the ferry one morning and back on her the next to look was the ruin still there where none ever came where you hid as a child slip off when no one was looking and hide there all day long on a stone among the nettles with your picture-book

Early drafts—Beckett also reworked his texts mercilessly—include many biographical reminiscence, some of which still make their way into the final version. Eoin O'Brien has written a marvellous book entitled The Beckett Country in which he’s provided photographs to go with all of Beckett’s writing. It was an immense undertaking and he was lucky that Beckett was feeling helpful because he wasn’t always. O'Brien had tracked down what he thought the place was Taylor’s Tower but that was not it:

Sam pored over the photographs, fascinated by the beauty of the place, but then, to my disappointment, informed me that he had never been there. Instead he directed me to Barrington's Tower, which, of course made much more sense in that it was close to Cooldrinagh, where he had been sent "supperless to bed" in punishment for his childhood peregrinations. When I asked him why he had changed the name, he said: "Eoin, there's no music in Barrington's Tower."[14]

Compare this now with Guillevic’s poem:

All this quivering

You feel within you,

Around you:

Collect it,

Assemble it,

Before it gets lost,

Make of it

Something like a sculpture

That will challenge time.

from Art Poètique (p.125)

A sculpture, a monument, a folly—it all feels about the same to me. A sculpture does not need words. It stands at a distance from them. The adjective ‘sculptural’ is one has been used when talking about how actors approach their parts in Beckett’s plays and I’m not just thinking of the part of the living sculpture in Catastrophe. Here Jonathan Kalb talks about the problems the actress Hildegard Schmahl had with the part of May in Footfalls:

![banshee banshee]() [T]he actress struggled to fulfil the author's wishes, to imitate the cold conspiratorial quality of his monotone line-readings while going through the motions of pacing in the slumped, infolded posture he demonstrated, "I can't do it mechanically," she would say. "I must understand it first and then think." But her vocal deliveries remained scattered, unconvincing, and laden with superfluous 'colour.'. . . Schmahl ultimately succeeded by means of a radical self-denial . . . for she eventually came to adopt the author's view of her task as primarily sculptural.[15]

[T]he actress struggled to fulfil the author's wishes, to imitate the cold conspiratorial quality of his monotone line-readings while going through the motions of pacing in the slumped, infolded posture he demonstrated, "I can't do it mechanically," she would say. "I must understand it first and then think." But her vocal deliveries remained scattered, unconvincing, and laden with superfluous 'colour.'. . . Schmahl ultimately succeeded by means of a radical self-denial . . . for she eventually came to adopt the author's view of her task as primarily sculptural.[15]

The renown Beckett scholar Stanley Gontarski has also commented on the “iconic, sculptural qualities of his works from Play onward.”[16] The wordless TV play Quad has also been described as “something akin to visual sculpture”.[17]

Beckett made veritable pilgrimages to further his knowledge of thirteenth- to sixteenth-century German sculpture.

[…]

Beckett’s stay in Bamberg … was dominated by sculptural study. He went to Kaiserdom, with its astonishing array of sculptural decoration on four separate occasions.[18]

In a piece of satire in The Onion they talk about a supposedly newly discovered Beckett play:

The 23 blank pages, which literary experts presume is a two-act play composed sometime between 1973 and 1975, are already being heralded as one of the most ambitious works by the Nobel Prize-winning author of Waiting For Godot, and a natural progression from his earlier works, including 1969's Breath, a 30-second play with no characters, and 1972's Not I, in which the only illuminated part of the stage is a floating mouth.[19]

It’s a funny article and worth a read but its point is a valid one. It’s what Beckett seemed to be working towards. And, again, Guillevic expresses a similar thought in Art Poètique:

I would like

To speak silence.

Silence

Speaks of the centre.

They are

What I need.

from Art Poètique (p.159)

Silence is not nothingness. That may seem an obvious thing to say but it is an important one. I am silent for much of the day but rarely am I doing nothing. My wife, and I imagine this applies to most wives, has a far greater need to initiate conversation than I do. When I think of most of our conversations I tend to play black if I can use chess as a metaphor; I respond—happily I should report (my wife is an interesting person)—but I don’t have as strong a need to vocalise as she does; I verbalise constantly (in my head) but I’m really not that fond of the sound of my own voice. And so it is true to say that all my writing comes as a natural result of bouts of prolonged silence. As Shalom Freedman puts it:

I waited for the Silence

Only then could I hear my own poem –

The Silence came and I began to write

from ‘I Waited for the Silence’

I found this comment by Erik Nakjavani, talking about Guillevic, thought-provoking:

Without silence, there would be nothing but sounds; therefore, no discernible utterance and therefore no language. So one can categorically state: Without the invisible, there would be no visibility, and without silence, there would be no language. Our desire to return to this original moment of silence and the invisible in creative activities intimates a profound and authentic nostalgia for the pre-historic, even pre-lingual world. Perhaps atavistic nostalgia gives us an experience however elementary of the primal silence and invisible that is the background of Guillevic’s concept of “living in poetry.”[20]

Also this from Louise Glück:

I love white space, love the telling omission, love lacunae, and find oddly depressing that which seems to have left nothing out.[21]

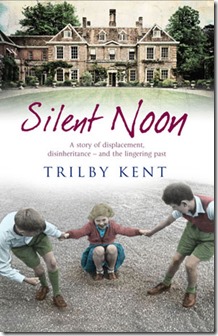

![WS Merwin WS Merwin]() Okay I would never go so far as to suggest that silence is poetry but what cannot be denied is that the best poetry is dripping with silences and lying in a pool of silence. As W. S. Merwin writes:

Okay I would never go so far as to suggest that silence is poetry but what cannot be denied is that the best poetry is dripping with silences and lying in a pool of silence. As W. S. Merwin writes:

To the Margin

Following the black

footprints the tracks

of words that have passed that way

before me I come

again and again to

your blank shore

not the end yet

but there is nothing more

to be seen there

to be read to be followed

to be understood

and each time I turn

back to go on

in the same way

that I draw the next breath

the wider you are

the emptier and the more

innocent of any

signal the more

precious the text

feels to me as I make

my way through it reminding

myself listening

for any sound from you

(as published in the 18/25 July 2005 issue of The Nation, p. 40)

Ironically Beckett’s white space is usually black. I suspect it’s a matter of practicality. Darkness is so much easier to manage on a stage but I wonder if he would have preferred his plays to be performed in an oasis that faded into whiteness. Here’s a perfect example from Ohio Impromptu:

![Ohio Impromptu Ohio Impromptu]()

He’s not here to ask but the importance of the black and white divide in his late plays has often been commented on, “not just a normal theatrical blackout, but a darkness of a different order.”[22]

Xerxes Mehta points out that Beckett’s darkness “is a part of the weave of his work, the most important single element of the image” […] “It should be as absolute as can be managed. Darkness at this level becomes a form of sense deprivation.”[23]

Deprivation, poverty, absence: it’s all the same thing. All that we have been provided with—our rations, if you like—are either the words on the page or the action in the spotlight. Black is not that far removed from white though. As Guillevic notes:

I know the strange

Variety of black

Which is called light.

from Sphere (p.108)

In the monochrome paintings of Japan called Sumi-e (or Suibokuga) the empty space, of the undrawn white of the paper is referred to as Yohaku. “Blank space is not simply unpainted areas; it is important to the composition of a painting and carries the same "weight" as the painted areas, often serving to set off or balance the painted motifs. … [I]n their paintings blank space functioned as ‘spirit’.”[24] The philosophy underlying this school of art is an interesting one. As Wikipedia puts it:

The goal of ink and wash painting is not simply to reproduce the appearance of the subject, but to capture its soul. To paint a horse, the ink wash painting artist must understand its temperament better than its muscles and bones. To paint a flower, there is no need to perfectly match its petals and colours, but it is essential to convey its liveliness and fragrance. East Asian ink wash painting may be regarded as an earliest form of expressionistic art that captures the unseen.[25]

Seems like a pretty decent definition of what poets aim to do with words, don’t you think? The blank page, the empty stage—that is where it all begins:

what would I do without this silence where the murmurs die

the pantings the frenzies towards succour towards love

without this sky that soars

above its ballast dust

what would I do what I did yesterday and the day before

peering out of my deadlight looking for another

wandering like me eddying far from all the living

in a convulsive space

among the voices voiceless

that throng my hiddenness

from ‘What Would I Do’ (Beckett’s own translation of que ferais-je sans ce monde )

In a 1969 interview Beckett said, "Writing becomes not easier, but more difficult for me. Every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness. Democritus pointed the way: 'Naught is more than nothing.'"[26] Beckett obviously liked the expression because, according to Deirdre Bair he used it on a number of occasions, with her and others; in fact these are the final words in her 1978 biography of him:

I couldn’t have done it otherwise, gone on I mean. I could not have gone on through the awful wretched mess of life without having left a stain upon the silence.[27]

And everyone knows the famous end to The Unnamable—“I can't go on, I'll go on.”—but this is the bit before it:

. . . it will be I, you must go on, I can't go on, you must go on, I'll go on, you must say words, as long as there are any, until they find me, until they say me, strange pain, strange sin, you must go on, perhaps it's done already, perhaps they have said me already, perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story, that would surprise me, if it opens, it will be I, it will be the silence, where I am, I don't know, I'll never know, in the silence you don't know, you must go on, I can't go on, I'll go on. (italics mine)

Mahood gabbles on as does Mouth in Not I and Winnie in Happy Days scrambling to find words. Winnie's entire raison d'être is to speak; words flow from her in an endless stream—"if only I could bear to be alone, I mean prattle away with not a soul to hear"—and that brings me back to Guillevic’s jaillissement. Words babble forth.

So where is silence located? In her introduction to her translation of Art Poètique Maureen Smith writes:

[Guillevic] created his own world which he refers to as a “domain”, a “kingdom” or a “sphere”, the place where something new is expected to come into existence, and in which he searches for a language of concreteness and clarity. […] In this domain, the search for language entails an experience of fullness and void, darkness and light, silence and singing. Sensitive, like his contemporary the painter Camille Bryen, to the existence of void and fullness, Guillevic recognises their presence “even in silence.” (Inclus, 132) It is this void that allows entry, allows the perception of the murmur at the heart of the void (Inclus, 135).

![findepartida_01_p findepartida_01_p]() This description brings to mind Beckett’s “skullscapes”. The word was not coined by Beckett himself[28] but I suspect he would have liked it. At the beginning of Murphy he, for example, describes Murphy’s mind as “a large hollow sphere, hermetically closed to the universe without.” An even more graphic description appears in his first short story, ‘Assumption’, where the protagonist retreats from speech into “a flesh-locked sea of silence”. Molloy talks about his “ivory dungeon” and this view is echoed by Malone and Mahood in the second and third parts of the trilogy.

This description brings to mind Beckett’s “skullscapes”. The word was not coined by Beckett himself[28] but I suspect he would have liked it. At the beginning of Murphy he, for example, describes Murphy’s mind as “a large hollow sphere, hermetically closed to the universe without.” An even more graphic description appears in his first short story, ‘Assumption’, where the protagonist retreats from speech into “a flesh-locked sea of silence”. Molloy talks about his “ivory dungeon” and this view is echoed by Malone and Mahood in the second and third parts of the trilogy.

Beckett’s skullskapes are not without windows though. The set for Endgamehas often been described as a skull with eye sockets and then we have the woman in Rockaby sitting at her upstairs window, searching the windows opposite to see another “one living soul” like herself.[29] Guillevic has written similar:

—What are you waiting for,

Standing at the window?

You seem all intent

On something outside.

—I'm not waiting for anything.

I'm not observing anything.

I see without looking.

—But I know that you are waiting.

Waiting for something,

Waiting to be invaded

By the now. from The Sea & Other Poems (translated by Patricia Terry)

Waiting; one of the major themes of Beckett’s oeuvre. And waiting is so often done in silence. Maybe not at first. At first we do stuff to distract ourselves but in time the distractions bore us and we settle in. And it’s then, free of distraction, that we are prepared. Waiting is never doing nothing: it is anticipating. It is ready. For “the now”.

Silence is clearly important to a great many writers, not just Beckett (who one might think had some kind of monopoly on it) and Guillevic. William S. Burroughs said, “Silence is only frightening to people who are compulsively verbalising,”[30]Thomas Carlyle said, “Under all speech that is good for anything there lies a silence that is better”[31] and Marshall McLuhan said, “Darkness is to space what silence is to sound, i.e., the interval”[32] but I think Alice Walker really hits the nail on the head with this quote which I’ll leave you with:

Everything does come out of silence. And once you get that, it’s wonderful to be able to go there and live in silence until you’re ready to leave it. I’ve written and published seven novels and many, many, many stories and essays. And each and every one came out of basically nothing–that’s how we think of silence, as not having anything. But I have experienced silence as being incredibly rich.[33] (italics mine)

P.S. After finishing this I discovered an English translation of that tiny Beckett poem. And I was way off:

listen to them

accumulate

word

after word

without a word

step

by step

one by

one

REFERENCES

[1] Rolf Breuer, ‘Flann O’Brien and Samuel Beckett’, Irish University Review, Vol. 37, No. 2, p. 340

[2] James Sallis, ‘Carnac and Living in Poetry’, Boston Review February/March 1999

[3] Stella Harvey, Myth and the Sacred in the Poetry of Guillevic, p.2

[4] Stephen Mitchelmore, ‘Beckett’s Silences’, This Space, 16 February 2011

[5] Stephen Mitchelmore, ‘Beckett’s Silences’, This Space, 16 February 2011

[6] Russell Smith, ‘Beckett, Negativity and Cultural Value’

[7] A legal term meaning breaking into a house, store, etc., by force; forcible entry. From the French which literally means a breaking open.

[8] Jaroslav Havir, The poetry of Guillevic : discourses of alienation, the erotic and ecology in Requiem, Terraqué, Carnac, Du Domaine and Maintenant, p.287

[9] Stella Harvey, Myth and the Sacred in the Poetry of Guillevic, p.3

[10] James Sallis, ‘Carnac and Living in Poetry’, Boston Review February/March 1999

[11] James Sallis, ‘Carnac and Living in Poetry’, Boston Review February/March 1999

[12] Samuel Beckett, Collected Poems, p.87

[13] James Sallis, ‘Carnac and Living in Poetry’, Boston Review February/March 1999

[14] Eoin O'Brien, The Beckett Country, p.220

[15] Jonathon Kalb, Beckett in Performance, p 63-64

[16] S.E. Gontarski ,‘Staging Himself, Or Beckett’s Late Style in the Theatre’, Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui, 6, p95

[17] David Pattie, The Complete Critical Guide to Samuel Beckett, p.94

[18] Mark Nixon, ‘Beckett and the Visual Arts’, Samuel Beckett's German Diaries 1936-1937, pp.149,152

[19]‘Scholars Discover 23 Blank Pages That May As Well Be Lost Samuel Beckett Play’. The Onion, 26th April, 2006

[20] Erik Nakjavani, ‘Homage to Guillevic: The Poet of Atavistic Nostalgia for the Primeval’, PSYART: A Hyperlink Journal for the Psychological Study of the Arts, December 15, 2009

[21] Quoted in David Godkin, Louise Glück: American Poetry's "Silent Soldier", Speaking of Poems, 15th April, 2012

[22] Junko Matoba, ‘Religious Overtones in the Darkened Area of Beckett’s Later Short Plays’, Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui, 9, p31

[23] Junko Matoba, ‘Religious Overtones in the Darkened Area of Beckett’s Later Short Plays’, Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui, 9, p31

[24] Japanese Architecture and Art users system: yohaku

[25] Wikipedia, Ink wash painting, Philosophy

[26] Charles A. Carpenter, Modern British, Irish, and American Drama: A Descriptive Chronology, 1865-1965 quoted in Samuel Beckett, 1906-1989: A Descriptive Chronology of His Plays, Theatrical Career, and Dramatic Theories excerpted with additions and other modifications

[27] Deidre Bair, Samuel Beckett, p.681

[28] The designation "skullscape" is Linda Ben Zvi's, from the recorded discussion that followed the production of Embers for the Beckett Festival of Radio Plays, recorded at the BBC Studios, London on January 1988.

[29] The composer Charles Dodge, met with Beckett in Paris to discuss preparing a performance version of Cascando. Beckett used the occasion to gush about a new apartment he had just taken. He was particularly excited because its window overlooked the yard of an adjacent prison. Charles asked what Beckett could see out his window. Beckett replied: "A face, sometimes part of one." – Schell, M., Beckett, Openness and Experimental Cinema, 1990/1998

[30] William S. Burroughs, The Job, pp.39,40

[31] Thomas Carlyle, The Works of Thomas Carlyle, p.27

[32] Marshall McLuhan, Toward a Spatial Dialogue, ch. 16,‘Through the Vanishing Point’

[33] Valerie Reiss, ‘Alice Walker calls God “Mama”’, beliefnet.com, February 2007

There’s nothing new under the sun. If you’re a writer and you really want to depress yourself spend an hour or so (as I’ve just done) clicking through the links on TVtropes.org. There you’ll find evidence to back up my opening statement. There’s nothing, nothing (Shultz, Hogan’s Heroes) that’s not been done before. So when I picked up Matt Haig’s new novel The Humans I expected to be treading some familiar ground. And I did. To list just a few tropes we come across in this book: Aliens Among Us, Voluntary Shapeshifting, The World Is Not Ready, These are Things Man Was Not Meant To Know, They Look Like Us Now, Humans Through Aliens Eyes, Literal-Minded, Out Of Character Alert, Humanity Is Infectious, Pinocchio Syndrome, What Is This Thing You Call Love?, Curiosity Causes Conversion, Interspecies Romance, Spot The Imposter, Humans Are Special. In many respects this list just about summaries the whole book. It’s all been done before. And all I have to say to that is: Who cares?

There’s nothing new under the sun. If you’re a writer and you really want to depress yourself spend an hour or so (as I’ve just done) clicking through the links on TVtropes.org. There you’ll find evidence to back up my opening statement. There’s nothing, nothing (Shultz, Hogan’s Heroes) that’s not been done before. So when I picked up Matt Haig’s new novel The Humans I expected to be treading some familiar ground. And I did. To list just a few tropes we come across in this book: Aliens Among Us, Voluntary Shapeshifting, The World Is Not Ready, These are Things Man Was Not Meant To Know, They Look Like Us Now, Humans Through Aliens Eyes, Literal-Minded, Out Of Character Alert, Humanity Is Infectious, Pinocchio Syndrome, What Is This Thing You Call Love?, Curiosity Causes Conversion, Interspecies Romance, Spot The Imposter, Humans Are Special. In many respects this list just about summaries the whole book. It’s all been done before. And all I have to say to that is: Who cares?  My Favourite Martian. I really loved The Strangerers and was sorely pissed I missed the last episode because the show ended on a cliffhanger and has never been released on DVD. I loved The Outer Limitsand The Twilight Zone. And I’ll tell you why I loved all of them: Because I could relate to them. Because I’m an alien too.

My Favourite Martian. I really loved The Strangerers and was sorely pissed I missed the last episode because the show ended on a cliffhanger and has never been released on DVD. I loved The Outer Limitsand The Twilight Zone. And I’ll tell you why I loved all of them: Because I could relate to them. Because I’m an alien too.  Now if this sounds a bit like David Hyde Pierce’s narration to The Mating Habits of the Earthbound Human then you’ve got the right idea. Our unnamed alien is assigned to earth, only not as an anthropologist because they’ve already pretty much made their minds up regarding the human race: they are violent, arrogant, greedy, untrustworthy, hypocritical and dangerous. The most dangerous of all was one Andrew Martin, a professor of mathematics living in Cambridge, England. I say ‘was’ because on Saturday, the seventeenth of April, he was abducted by these aliens who extracted what they needed from him, killed him and then assigned one of their own to replace him. So I should probably have included the Kill and Replace trope in my list at the start too. This alien’s brief is a simple enough one: Destroy all physical evidence that a solution exists to the Riemann hypothesis and eliminate all humans who are even aware that there is a solution.

Now if this sounds a bit like David Hyde Pierce’s narration to The Mating Habits of the Earthbound Human then you’ve got the right idea. Our unnamed alien is assigned to earth, only not as an anthropologist because they’ve already pretty much made their minds up regarding the human race: they are violent, arrogant, greedy, untrustworthy, hypocritical and dangerous. The most dangerous of all was one Andrew Martin, a professor of mathematics living in Cambridge, England. I say ‘was’ because on Saturday, the seventeenth of April, he was abducted by these aliens who extracted what they needed from him, killed him and then assigned one of their own to replace him. So I should probably have included the Kill and Replace trope in my list at the start too. This alien’s brief is a simple enough one: Destroy all physical evidence that a solution exists to the Riemann hypothesis and eliminate all humans who are even aware that there is a solution.  I’ve made my point. In so many respects this book is derivative and even fairly predictable. I should be panning it rather than praising it but I loved it. From the first page to the last. The short chapters kept the action rolling along and it was so easy to say to myself: Just one more chapter. It began, as I’ve said, in a light-hearted manner and although the humour never disappears completely the book does become more serious as it progresses. It never quite ends up as The Man Who Fell to Earth but it does ask some hard-hitting questions. If you’re not much of a reader though I suggest you locate a copy of the book, open it up to page 271 and tear out the four leaves that comprise the chapter entitled ‘Advice to a human’, fold them up, tuck them inside your jacket pocket and read them whenever you have a spare moment, sitting on the bus or train or waiting to be seen by the doctor. There are ninety-seven aphoristic statements here. Let me share a few:

I’ve made my point. In so many respects this book is derivative and even fairly predictable. I should be panning it rather than praising it but I loved it. From the first page to the last. The short chapters kept the action rolling along and it was so easy to say to myself: Just one more chapter. It began, as I’ve said, in a light-hearted manner and although the humour never disappears completely the book does become more serious as it progresses. It never quite ends up as The Man Who Fell to Earth but it does ask some hard-hitting questions. If you’re not much of a reader though I suggest you locate a copy of the book, open it up to page 271 and tear out the four leaves that comprise the chapter entitled ‘Advice to a human’, fold them up, tuck them inside your jacket pocket and read them whenever you have a spare moment, sitting on the bus or train or waiting to be seen by the doctor. There are ninety-seven aphoristic statements here. Let me share a few:  Matt Haig was born in Sheffield, England in1975. He writes books for both adults and children, often blending the worlds of domestic reality and outright fantasy, with a quirky twist. His bestselling novels are translated into 28 languages. The Guardian has described his writing as 'delightfully weird' and the New York Times has called him 'a novelist of great talent' whose writing is 'funny, riveting and heartbreaking'.

Matt Haig was born in Sheffield, England in1975. He writes books for both adults and children, often blending the worlds of domestic reality and outright fantasy, with a quirky twist. His bestselling novels are translated into 28 languages. The Guardian has described his writing as 'delightfully weird' and the New York Times has called him 'a novelist of great talent' whose writing is 'funny, riveting and heartbreaking'.

Hospital

Hospital

between ‘stranger’ and ‘outsider’ whatever that may be. Why, I wonder, did English not simply absorb the word as it has done with so many foreign expressions like vis-à-vis, tête-à-tête and mano-a-mano?

between ‘stranger’ and ‘outsider’ whatever that may be. Why, I wonder, did English not simply absorb the word as it has done with so many foreign expressions like vis-à-vis, tête-à-tête and mano-a-mano?

Ben Marcus

Ben Marcus

Harold Pinter

Harold Pinter

Jon Courtenay Grimwood

Jon Courtenay Grimwood

As with Ozeki’s most recent book,

As with Ozeki’s most recent book,  My Year of Meats won the Kiriyama Pacific Rim Award, the Imus/Barnes and Noble American Book Award, and a Special Jury Prize of the World Cookbook Awards in Versaille. All Over Creation was awarded a 2004 American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, as well as the Willa Literary Award for Contemporary Fiction. A Tale for the Time Being won the IBW Book Award 2013.

My Year of Meats won the Kiriyama Pacific Rim Award, the Imus/Barnes and Noble American Book Award, and a Special Jury Prize of the World Cookbook Awards in Versaille. All Over Creation was awarded a 2004 American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, as well as the Willa Literary Award for Contemporary Fiction. A Tale for the Time Being won the IBW Book Award 2013.

Cally Phillips

Cally Phillips