![antipoet antipoet]()

The true poet is willing to give up poetry in order to find poetry– Henry Rago

STOP RACKING YOUR BRAINS

nobody reads poetry nowadays

it doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad

– Nicanor Parra[1]

A friend of mine made this comment a while back: “Your writing is very much part of the 'anti-poetry' tradition, as is Larkin's.” She meant no harm by it—I have no problem being compared to Larkin—and I’m pretty sure I know what she meant when she used the term ‘anti-poetry’ but it started me thinking and you know what happens when I start thinking. Antipoetry: the obvious meaning is ‘against poetry’ or poetry haters (mysomousoi as they were known at the time of the English Renaissance) but that’s not what antipoetry is really about.

In his book, Toward an Image of Latin American Poetry, Octavio Armand writes: “Every poet is an antipoet. The reverse is not always true.”[2] One way of looking at a statement like that is to say that all poets can write prose but not all prosers can write poetry—something I tend to agree with—but the relationship between prose and poetry is not a simple either/or situation. And what about antipoetry? Is antipoetry simply chopped-up prose or is there something in between?

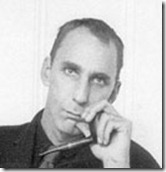

Arguably the world’s best known antipoet is the Chilean, Nicanor Parra, who, at the end of 2011 was awarded Spain’s Cervantes Prize (considered the Spanish-speaking world’s highest literary honour) which comes with a cash sum of €125,000 so no small honour. He’s also been nominated several times for the Nobel Prize. He’s 97 now but his name became forever bound to the notion of antipoetry when, in 1954, he published Poemas y Antipoemas (Poems and Antipoems). He did not coin the term however.

The foundation of the antipoetry movement (if indeed such a thing exists nowadays) lies with another Chilean poet, Vicente García-Huidobro Fernández, but known as Vicente Huidobro. He was a Creationist, in fact he founded the movement. Creationism held that a poet should bring life to the things he or she writes about, rather than simply describe them. Huidobro saw a poem as a truly new thing, created by the author for the sake of itself—that is, not to praise another thing, not to please the reader, not even to be understood by its own author. He defined himself as an "antipoet and magician" and decreed in his “Manifesto Perhaps” that “THE GREAT DANGER TO THE POEM IS THE POETIC,” that to “add poetry to what has it already without you” is to pour honey on honey, “it’s sickening.”[3] Well said that man. He was not the first Latin American antipoet however. The Peruvian Ultraist poet Enrique Bustamente Ballivan had already published a book called Antipoemas in 1926 of which I can find next to nothing online other than it’s supposed to be worth reading.

In an interview in 1938, Huidobro proclaimed that “[m]odern poetry begins with me.”[4] A similar claim was made by Parra in 1962 when he declared, “Poetry ended with me.”[5] I have little doubt that there’s a long queue forming after them who would want to make similar hyperbolic claims although I’m certainly not one of them. Both poets were very clearly aware of what had passed for poetry before them and were keen to draw a line under it but let’s face it that happens every generation anyway.

If you were to ask someone to name a famous Chilean poet from this time neither of these names will probably top the poll; that honour is most likely to go to Pablo Neruda who, incidentally, did win the Novel Prize in 1971. Neruda’s poems are often passionate odes to love and nature, verbose and adjectival in approach featuring a cornucopia of nature-derived imagery. (He’s not a poet I know well so I’m basing this on what I’ve read about him online.) A brief example:

In Praise of Ironing

Poetry is pure white.

It emerges from water covered with drops,

is wrinkled, all in a heap.

It has to be spread out, the skin of this planet,

has to be ironed out, the sea’s whiteness;

and the hands keep moving, moving,

the holy surfaces are smoothed out,

and that is how things are accomplished.

Every day, hands are creating the world,

fire is married to steel,

and canvas, linen, and cotton come back

from the skirmishings of the laundries,

and out of light a dove is born—

pure innocence returns out of the swirl.

(translated Alastair Reid)

![nicanor-parra nicanor-parra]() Parra, like Philip Larkin, chose to formulate his poetry using vernacular, unrhetorical, direct language. Parra, it should be noted, was a careful reader of British poetry particularly T S Eliot. Larkin himself also acknowledges Eliot as a major influence upon his making as a poet. An odd hero I’ve often thought as Eliot’s work has always been beyond me; too clever for its own good. Parra sought to demystify poetry and make it accessible to a wider audience. Although others are quick to point out the differences between the two men, Parra himself had this to say:

Parra, like Philip Larkin, chose to formulate his poetry using vernacular, unrhetorical, direct language. Parra, it should be noted, was a careful reader of British poetry particularly T S Eliot. Larkin himself also acknowledges Eliot as a major influence upon his making as a poet. An odd hero I’ve often thought as Eliot’s work has always been beyond me; too clever for its own good. Parra sought to demystify poetry and make it accessible to a wider audience. Although others are quick to point out the differences between the two men, Parra himself had this to say:

Not one day goes by without my thinking of him at least once. I read him attentively, I follow with increasing amazement his yearly displacement along the Zodiac, I analyze him and compare him with himself. I try to learn whatever I can.[6]

Admiring someone and seeking to emulate him or her is something else. I think it’s fair enough to talk about Eliot as a “poet’s poet.”[7] Larkin and Parra were never aiming that high; they were content to be the people’s poet and both achieved that in their respective countries.

Oftentimes Larkin’s poetry comes across as if it has had all the poeticness stripped out of it and if it didn’t include rhymes at the end of the lines and be left-indented you might be forgiven for thinking that it was, in fact, chopped-up prose. An interesting point though is made by Ryan Hibbert in his book, Proving Poetry: Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin, Now:

[A] literary text can sound like ordinary speech, but it never is ordinary speech, which it ultimately defines itself against; the “common” speech in Larkin’s poetry assumes … “a special character” it otherwise lacks. Swearing, for example, takes on the special character of a poet swearing, or swearing in a poem—an extended meaning it lacks in everyday conversation.[8]

The poem of his that I always return to—it’s my perfect poem—is ‘Mr Bleaney’ and the perfect synthesis between ‘poetry’ and ‘non-poetry’. Whether it can be classified as ‘antipoetry’ is another matter (I’ll come back to that) but you can find a detailed consideration of the poem beginning on page 60 of Hibbert’s book.

Of the two—I’m comparing Parra and Huidobro here—I relate more to Parra in his approach to poetry. He reminds me of William Carlos Williams (who compared a poem to a machine) when he wrote in his Manifesto that a poet is not an alchemist (or a magician) but a man like any other, a carpenter who constructs walls, doors, and windows, and the poet’s job is? In 'Letters from a poet who sleeps in a chair' he says:

V

Young poets

Write as you will

In whatever style you like

Too much blood has run under the bridge

To go on believing

That only one road is right.

In poetry everything is permitted.

With only this condition of course,

You have to improve the blank page.

(translated by Miller Williams)

Later he says it a little differently:

XIII

The poet's job is

To improve on the blank page

I don’t think that’s possible.

(translated by David Unger)

(Shades of Beckett there too.) What this brings to my mind is a distinction between two kinds of poetry: nature poetry (in the broadest sense, not just poems about brooks and daffodils) and urban poetry (again taking a broad brush approach to the term). Two words that frequently come up when people write about antipoetry are ‘urban’ and ‘colloquial’, colloquial speech as opposed to the refined language normally associated with poetry. Colloquialisms are sometimes referred to collectively as "youknowhatitis language" but, as William McIlvanney has pointed out, the language of the common people is saturated with metaphors and is far from unpoetic without ever appearing pretentious.

In The Antipoetry of Nicanor Parra, Edith Grossman details three objectives of “the theoretical course” that Parra “set for himself after the publication of his Cancionero sin Nombre.” The first objective was to free poetry from the domination of the metaphor, which he terms “the abuse of earlier poetic language.” His antipoetry, understood as a liberation from what he termed an “abusive” style, would rather avoid such “poetic” language in favour of direct communication with the reader. Second, antipoetry should “depend on the commonplace in all its ramifications, that it decisively reject the rarefied and the exotic, both thematically and linguistically.” By this, Grossman elucidates, Parra meant that “the language of literature must be no different from the language of the collectivity . . . language reflects the life of the people. . . “Third, Parra has reaffirmed that his writing was leading directly to a “purely national expression” because the poet cannot remove himself from the community, the tribe. Thus the poet “should use colloquialisms peculiar to his own country, even if readers from other areas find them difficult to understand.”[9] (bold emphasis mine)

Pablo García writes of the movement in Chile: “…our motto was war on the metaphor, death to the image; long live the concrete fact and clarity.”[10]

Parra expressed his intention for antipoetry most clearly in his poem ‘Manifesto’ contained in his 1972 collection Emergency Poems:

Ladies and gentlemen

is our final word

– Our first and final word –

The poets have come down from Olympus

For the old folks

Poetry was a luxury item

But for us

It’s an absolute necessity

We couldn’t live without poetry.

Through the course of this poem he condemns a variety of styles of poetry:

We repudiate

The poetry of dark glasses

The poetry of the cape and sword

The poetry of the plumed hat

We propose instead

The poetry of the naked eye

The poetry of the hairy chest

The poetry of the bare head.

We don’t believe in nymphs or tritons.

Poetry has to be this:

A girl in a wheatfield –

Or it’s absolutely nothing.

![Larkin Larkin]() Many have struggled to come up with a definition of poetry that we in the 21st century are comfortable with. Form used to be the crucial thing but now that just about everyone is writing free verse we have to dig a little deeper. At its core I believe all poetry is metaphorical even if not a single metaphor or simile is used; very few poems are ever taken just literally. Even a straightforward poem like ‘Mr Bleaney’ which describes a man agreeing to rent a room in essence doesn’t stop there; it takes us to the cliff’s edge and leaves us there. Poetry is all around us. Football commentators describe the technical skill of players as “pure poetry”. Here’s a sentence from an article about children:

Many have struggled to come up with a definition of poetry that we in the 21st century are comfortable with. Form used to be the crucial thing but now that just about everyone is writing free verse we have to dig a little deeper. At its core I believe all poetry is metaphorical even if not a single metaphor or simile is used; very few poems are ever taken just literally. Even a straightforward poem like ‘Mr Bleaney’ which describes a man agreeing to rent a room in essence doesn’t stop there; it takes us to the cliff’s edge and leaves us there. Poetry is all around us. Football commentators describe the technical skill of players as “pure poetry”. Here’s a sentence from an article about children:

[S]eeing her laugh and suck on those fat little fingers…that was pure poetry, if it ever existed.

From a comment talking about a blog post about rescuing horses:

Joe, that was pure poetry.

From a poem about canoeing:

It was pure poetry

when you were

a lone traveller

in your canoe and

suddenly the sky

darkened by a flock

of migrating birds.

There used to be a time when some subjects were considered verboten. But then there was a time where women didn’t show their ankles in public. It’s just a matter of readjusting how you see things to realise that what you’re perceiving is poetry. It’s like music. I’m quite sure that most Baroque composers would cover their ears if they were exposed to some of the stuff that twentieth century turned out and called ‘music’ but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t music. And the same goes for what poets like Parra call ‘antipoetry’—the term is misleading because his antipoems are not against Poetry but a response to a certain kind of poetry. His poetry is antiheroic, it eschews high rhetoric and elevated language but it is still poetry.

In his thesis Notes on Insufficient Laughter Ronn David Silverstein writes:

Antipoetry is flat, understated; and relaxed; antipoetry “returns poetry,” as Parra says, “to its roots;” antipoetry is honest, unadorned, unlyrical, nonsymbolist; in antipoetry what you see is what you see; antipoetry is chiselled, solid. Antipoetry dispenses with stock poetical devices; instead, it offers dark humour, disjointed logic, flatness of tone and directness of statement.

He contrasts these to “the ‘deep image poem’ (which is hyperbolic and associative in its images) […] a phrase coined by Robert Kelly in the 1940s to describe what Robert Bly was doing through his Fifties Press, namely, his translations of the Spanish poets: Lorca, Jiménez, Vallejo and others.” (You can read a long article about deep image poetry here.) What is interesting is that Bly openly criticised Pound’sImagist movement describing it as “Picturism. An image and a picture differ in that the image, being the natural speech of the imagination, cannot be drawn from or inserted back into the real world.”[11]

In his book Leaping Poetry Bly explains his concept of the deep image. He says that the deep image concerns itself with a central image that “should exist at the centre of the poem and sprout from the unconscious mind, uniting the known world, i.e. the poem’s content, with the unknown world, i.e. the poem’s language, by the act, on the poet’s part, of creative fusion.” In the poem ‘Driving Toward the Lac Qui Parle River’ this leap occurs in the final stanza and I find myself thinking about the closing image to ‘Mr Bleaney’ and wonder just how well it fits the criterion:

But if he stood and watched the frigid wind

Tousling the clouds, lay on the fusty bed

Telling himself that this was home, and grinned,

And shivered, without shaking off the dread

That how we live measures our own nature,

And at his age having no more to show

Than one hired box should make him pretty sure

He warranted no better, I don't know.

Is it an intellectual image, a room imagined as a coffin? Does that fear sprout from the conscious or the unconscious mind? I’m not going to labour the point but it’s something to think about.

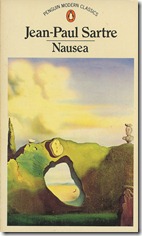

![williamcarloswilliams williamcarloswilliams]() After I left school and started to examine poets that weren’t on the curriculum (and hence not British) I quickly discovered another who spoke my tongue: William Carlos Williams. Wallace Stevens considered his work “anti-poetic,”[12] (describing "the real" instead of "the sentimental") while H.D. found him “commonplace, common and banal.” I found his work pure, like the music of Pärt, stripped down to its essentials. But it was most definitely poetry. And yet I find that Williams is another poet whose work often gets referred to as antipoetry; Dave Oliphant has written an entire book comparing his work to Parra’s. The most obvious comparison is their insistence on working with normal speech:

After I left school and started to examine poets that weren’t on the curriculum (and hence not British) I quickly discovered another who spoke my tongue: William Carlos Williams. Wallace Stevens considered his work “anti-poetic,”[12] (describing "the real" instead of "the sentimental") while H.D. found him “commonplace, common and banal.” I found his work pure, like the music of Pärt, stripped down to its essentials. But it was most definitely poetry. And yet I find that Williams is another poet whose work often gets referred to as antipoetry; Dave Oliphant has written an entire book comparing his work to Parra’s. The most obvious comparison is their insistence on working with normal speech:

His late development of ‘the variable foot’ allowed him to be discursive without abandoning the cadence and rapidity of natural speech. The order of speech, of prose statement, has replaced a repetitive, metronomic pattern, as the expected element in Williams' line. By and large, the line units are dictated by speech, but they have a flexibility and offer a range of possible discovery far exceeding those of traditional meter. Looking for criteria to judge ‘the variable foot’ we may suggest: (a) is it natural, true to speech? (b) are the variations vital and interesting? For Williams the anti-poetic would be aping of traditional literary forms or copying the speech and/or measure of others.[13]

What Stevens wrote in the introduction to Williams's Collected Poems 1921-1931 was this:

His passion for the anti-poetic is a blood passion and not a passion of the inkpot. The anti-poetic is his spirit's cure. He needs it as a naked man needs shelter or as an animal needs salt. To a man with a sentimental side the anti-poetic is that truth, that reality to which all of us are forever fleeing.

And this is how Williams responded:

I was pleased when Wallace Stevens agreed to write the Preface but nettled when I read the part where he said I was interested in the anti-poetic. I had never thought consciously of such a thing. As a poet I was using a means of getting an effect. It's all one to me—the anti-poetic is not something to enhance the poetic—it's all one piece. I didn't agree with Stevens that it was a conscious means I was using. I have never been satisfied that the anti-poetic had any validity or even existed.[14]

As the book was published in 1934 I think it can be taken as read that Stevens is not referencing Huidobro and that he is attempting his own definition of antipoetry. Williams is not an antipoet—he had very clear ideas on what a poem should be and be about—but he is an anti-traditionalist and that’s where much of the common ground lies when you compare him to Parra.

What I find noteworthy is that, in a letter to William Rose Benét written in 1939, Stevens mentions that his favourite poem (of his own) was ‘The Emperor of Ice-Cream’ because it wore “a deliberately commonplace costume, and yet seems to me to contain something of the essential gaudiness of poetry”[15] and a few days later he clarified this when he said, “This represented what was in my mind at the moment, with the least possible manipulation.”[16] Five months later he admits that “[t]he poem is obviously not about ice cream, but about being as distinguished from seeming to be.”[17]

My gut feeling is that when he made his comments concerning Williams he simply hadn’t spent enough times with the poems because so many of his poems (Williams’, I mean) can seem superficial until you’ve lived with them for a while. Just look at the amount of stuff that’s been written about ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’ for instance. Williams and Stevens “were like brothers who might break up a fight to unite in the face of a bully.”[18] One such “bully”, interestingly enough, was T S Eliot:

Williams felt the pressure of a poetic contest with T S Eliot, whom he considered a deadly threat to everything he stood for. Stevens also opposed himself to Eliot. He wrote, “Eliot and I are dead opposites and I have been doing about everything that he would not be likely to do.”[19]

As I’ve mentioned already Parra and Larkin were also reading Eliot and no doubt their choice of direction was a reaction to what they read even if they weren’t so vocal about it.

Larkin was anti- lots of things—anti-sentimental, anti-romantic, anti-life even—but I’m not so sure he would have appreciated being called antipoetic. His early work shows his influences—Yeats in particular, and later of Hardy—but on the whole his technique is nothing revolutionary; his subject matter, however, is. And that’s where he and Parra would find themselves nodding in agreement. The aim of his poetry, he suggested, was to give the impression of "a chap chatting to chaps."[20] I think that was what first struck me about him: I didn’t feel I was being talked down to. Years later, in ‘The Journey Back,’ the opening poem of his 1991 collection Seeing Things, Heaney would describe him as “[a] nine-to-five man who had seen poetry.” I think that would be a fair description of William Carlos Williams and myself too; not sure about Parra—do theoretical physicists work nine to five?

What do they mean when they talk about a flat style of poetry? Surely all poetry is flat. (Yes, I’m being facetious.) What’s the opposite of ‘heightened’ language? One would imagine whatever the lingua franca of the day is. We don’t like ornate furniture these days or fancy flock wallpaper and I doubt if any songs in the charts have very many trills or appoggiatura in them (they’re the twiddley bits Baroque composers were so fond of). We like monochromes and straight edges. And the same goes for our poetry. The problem is when you’re used to buying your furniture from Ikea and having your songs written by Stock, Aitken and Waterman (or whoever their 21st century equivalents are) then you stop appreciating handmade furniture and singer songwriters. (Again, I’m being facetious.) A friend of my dad’s once told me, “Jimmy, there aren’t any engineers anymore, just fitters.” And he’s right. You take your car in to get repaired and all they do is whip out one component and bung in another. Your phone breaks down, you buy another.

In his book Ensouling Language, Stephen Harrod Buhner, opens the chapter entitled ‘You Must Begin with Something Deeper in the Self’ with a quote from Robert Bly:

Some people who are terrified of grandiosity spend their vital energy defending themselves from the godlike furnace that is cooking inside them. They are the flat people. Side by side with the light poetry we have the flat poetry of the universities, flatter than any poetry ever known in the world before.

In this chapter Buhner presents us with a sweeping statement: You must not extend awareness further than society wants it to go. He doesn’t agree with it but he believes that that belief is something that holds many writers back, encourages them to play safe and, of course, there will be those that do pull their punches for fear they might overstretch themselves or that they might produce something their audience (if they’re lucky enough to have an audience) might turn their noses up at. And I have to wonder if that’s what I do which is why someone might tar me with the antipoetry brush. But I don’t think that’s the case. I always worry about things that are defined by what they’re not and I find that I’m struggling to find a consensus regarding flat poetry. I was intrigued by part of this comment by Robert:

Yet I really think great poetry elicits more similarity than dissidence of response from most audiences in a way that is shockingly more similar to a computer runtime environment than it would appear at first glance. While both code and poems appear flat on the page or screen, when executed both forms present myriad opportunities to branch down different paths. But the reality is that poetry gives you no choice -- only the infinite illusion of choice through allusion, implication, reference, rhyme, nonsensical meaning, seductive sounds and rhythms, and a multitude of other techniques that simultaneously tell the mind there is one thing going on as well as (in subtext) thousands.

A poem is not code. Yes, it’s true we encode meaning, but we do so in a very imprecise way. In HTML <b> and </b> have very specific meanings—bold on, bold off—and they never change no matter what the context. I don’t think a poem has been written so flat that a person with an active imagination couldn’t take it somewhere its author didn’t intend or expect it to go. That said the less technique you apply the fewer opportunities arise.

Okay, so let’s look at an antipoem:

Antipoetry

Like Nicanor Parra I write antipoetry

antipoems for antipeople in antibooks

antipoems for anticritics for antireaders

antipoetry for antiassholes in the antimatter

antielectrons in the antiatoms for antideaf

in my antiadaptation to the literary world

in the antigroup of the antiliterature

antipoetry for antieditors for antiprizes

for antilectors for anticorrectors for antipublishers

and it is not because I don't like poetry or

because I don't like critics, it is because,

like any other antipoet I only know

how to write

antipoetry.

Mois Benarroch

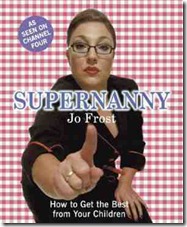

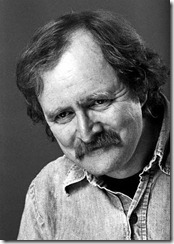

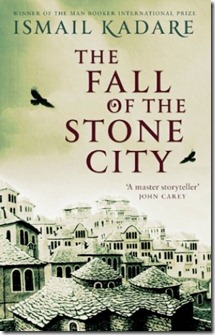

![Mois Mois]() Mois Benarroch is a Moroccan poet the same age as me; he even looks a bit like me. And he is far from being someone who one might label as simply an antipoet. I like this piece I have to say. I could have written it, although it’s a bit light for me, to be honest. He’s actually quite a prolific writer—a polyglot no less—and I got caught up reading about him. I was particularly struck by a comment he made in an interview about the “outsiderness” of his poetry:

Mois Benarroch is a Moroccan poet the same age as me; he even looks a bit like me. And he is far from being someone who one might label as simply an antipoet. I like this piece I have to say. I could have written it, although it’s a bit light for me, to be honest. He’s actually quite a prolific writer—a polyglot no less—and I got caught up reading about him. I was particularly struck by a comment he made in an interview about the “outsiderness” of his poetry:

This is definitely the recurring theme in my writings. It spreads all over, from being an outsider as a Jew, or as a writer (and Edmond Jabes would say that every writer is a Jew) to feeling like a different kind of Jew and not really part of the mainstream of Judaism: that is being a Sephardic Jew. Maybe that’s what poetry is about: being outside, being different and writing a different poem.[21]

I find reading about schools of poetry interesting but I’ve never found myself drawn to any group. In that respect I, too, feel like an outsider in the poetry world. The notion that I might be a closet antipoet nettles, to use Williams’ word; I don’t like being classified. Classification inclines readers to limit their expectations and although it’s true I veer towards a certain style of poetry I’ve yet to find a single poet out there who writes like me. I relate strongly with what Benarroch says here. I’ve always felt different and that my poetry was different. I can relate to lots of different poets but I’m loathe to set down—even for myself—rules as to what I think a poem should be or do. So no manifestos from me; not this week.

In his poetry collection, Abstracts, John O’Loughlin gives his thoughts on the differences between poetry and antipoetry:

[W]here does poetry end and antipoetry begin? … I think we can answer this question … by contending that, although in practice the two kinds of poetry often overlap, the poetical ends by singing the praise of artificial beauty, while the antipoetical begins in a preponderating concern for the metaphysical … as a vehicle for the exploration of truth. Thus we have good reason to believe that, as with philosophy and antiphilosophy, poetry ends and antipoetry begins on a petty-bourgeois level, the one at a climax to a concern for appearances in the most artificial context, i.e. as pertinent to the urban/industrial environment, and the other at the inception to a concern for essences in the least spiritual context, i.e. as pertinent to the intellectual elucidation of metaphysical speculation.[22]

As Goethe wrote, "the unnatural, that too is natural," and I think this is where I come in. If, as O’Loughlin suggests, poetry ends “by singing the praise of artificial beauty” it certainly begins by praising Nature and those were the poems that I reacted against, the ones we got taught at Primary School that I moan about all the time, poems about brooks or daffodils or sad sacks sauntering down to the sea. I never studied the metaphysical poets but a part of me wishes I had because I think I would have found much to relate to. I live in an urban setting and am interested in writing about what I can relate to so in that respect I can be called an antipoet based on this criteria plus I’m just about the least spiritual person you are likely to meet so perhaps I am an antipoet at my core. I agree with Parra when he says that the function of language is “that of a simple vehicle and the material with which I work, I find in daily life.”[23]

But there are differences: I have not forsaken the metaphor or the image although I use both with care. The bottom line is that I don’t much care for labels and I’ve no great desire to align myself with any school of poetry. I do aspire to write clear and understandable poetry (but not superficial poetry) that has structure but is not a slave to structure and by that I mean that I believe that a poem’s shape evolves naturally in its writing which is why I could never see myself setting out to write a sestina or a sonnet and forcing my words into that predefined shape. We all look back when creating metaphorical images but the further back we look the more likely we are to lose our readers so I prefer contemporary cultural references which is why no nods to Greeks gods in any of my poems. Let me leave you with a few poems that I think might pass as antipoems. You decide.

After Pinter

I am a great man.

People depend on me to say great things.

They expect me to say great things.

I expect I am saying something great right now.

Things appear greater when I say them.

It is a terrible burden, of course,

a terrible responsibility, in fact,

to always have to say something great,

to be great to order; that said

people believe I am being great

even when I am being normal.

To them my normal is just great.

They need me to be great

ergo I am great.

“That was great,” they’ll say

and they’ll believe that to be true

but at the same time they’ll be thinking:

I thought great might be greater than that

but what do I know, he’s the great man, not me.

27 January 2010

The Wrong Nudes

My daughter bought me a book, an album,

with pictures of naked women in it.

Of course the wrong women were naked but

how was she to know that that might matter?

That said, realisation is one thing,

acceptance another and approval,

first tacit, then open, quite something else.

Nudity is such a disappointment.

I have never really understood when

nakedness becomes art or if indeed

openness is always a good idea.

She said the book had a dented spine which

is how she could afford it and then we

moved seamlessly onto other matters.

09 March 2009

An Honest Poem

Here's the deal,

mate – we might as well be

up front about all this –

what you need to do is

read this and forget it.

It shouldn't be so hard.

I'm sure you've read and

forgotten hundreds

of poems, dozens at

least. So, let's cut to the

chase – yes? – and not waste each

other's time.

09 November 2008

Everyone's a Critic

So we got

this writer and this reader –

seems like a match

made in heaven –

the catch is,

the writer keeps writing things

the reader doesn't want to read

whilst the reader insists on reading stuff

the writer hasn't a clue how to write.

Go figure.

But they're stuck with each other,

joined at the hip.

Think about it.

Anyhow

one day the writer's had it:

"So what the fuck should I write then?"

The reader doesn't even miss a beat:

(well maybe just one) ... "You got a pen?"

22 August 2004

I Spy

You shouldn't look at women's chests;

they mind if you look.

They know you can see

but you're not supposed to look.

But you're allowed to notice;

they expect you to notice.

It's hard to see why you can't look

at what you've just seen

but those are the rules

even though they don't make sense.

21 October 1997

FUTHER READING

Huidobro and Parra: World-Class Antipoets

Although I Havent't Come Preparraed: The Poetry And Antipoetry of Chile [sic]

Poetry of the Sneeze: Thomas Merton and Nicanor Parra

Gardens, Cemeteries, and the Abyss: Symbolic Spaces in a Selection of Nicanor Parra’s Anti-Poetry

Merton, ‘Cables to the Ace’, Anti-Poetry

The Manifesto of Antipoetry (Coe Review, Number 8, 1977, p.10)

The Aesthetics of Anti-Poetry Manifesto: Poetry Criticism by an Anti-Poet

A large collection of Parra’s poetry can be accessed here.

REFERENCES

[1] Nicanor Parra, ‘Something Like That,’ translated by Liz Werner

[2] Octavio Armand, Toward an Image of Latin American Poetry, p.10

[3] For “Poeta / Anti poeta,” see Canto I in Vicente Huidobro’s Altazor (2003: 34), and for “antipoeta y mago,” see Canto IV (94). For Huidobro’s all-caps manifesto and his further declarations on the dangers of the poetic, see The Selected Poetry of Vicente Huidobro, ed. David M. Guss (1981: 76). Huidobro’s prose statements are translated into English from his Manifestes, a volume written in French.

[4] David M. Gussed., The Selected Poetry of Vicente Huidobro, x

[5] Nicanor Parra, Antipoems: New and Selected, pp.42-45

[6] Nicanor Parra, Welcoming Speech Honouring Pablo Neruda

[7] Peter Monro Jack writing in The New York Times quoted in Jewel Spears Brooker ed., T. S. Eliot, The Contemporary Reviews, p.xxix

[8] Ryan Hibbert, Proving Poetry: Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin, Now, p.57

[9] Julio Marzán, ‘The Poetry and Anti-Poetry of Luis Palés Matos: From Canciones to Tuntunes’, Callaloo, 18.2, pp. 506-523

[10] Pablo García, ‘Contrafigura de Nicanor Parra’, Atena, Jan/Feb 1955, p.157

[11] Kevin Bushell, ‘Leaping Into the Unknown: The Poetics of Robert Bly's Deep Image’, Modern American Poetry

[12] In his article ‘William Carlos Williams: This is just to say…’ Vancouver-based consultant Juna Wood states that “Wallace Stevens affectionately called Williams' work the 'anti-poetic' in an essay…” (italics mine) I have no idea where he gets ‘affectionately’ from but no doubt it’s based on something he’s read in the past. Dickran Tasjian writes, however, that "Williams was annoyed by Stevens' contention that the anti-poetic was an outlet, a mask, for sentimentality. Williams argued instead that the poetic and the anti-poetic were of a piece, creation and destruction, art/anti-art, inextricably bound together in a dialectic." Dickran Tasjian, William Carlos Williams and the American Scene, 1920-1940, pp.59,60

[13] Charles Doyle, William Carlos Williams and the American Poem

[14] William Carlos Williams, I Wanted to Write a Poem: The Autobiography of the works of a Poet, p.52

[15] Quoted in Warren Carrier, ‘Commonplace Costumes and Essential Gaudiness: Wallace Stevens’“Emperor of Ice Cream,”’ College Literature, 1974

[16] Ibid

[17] Ibid

[18] Martha Helen Strom, ‘The Uneasy Friendship of William Carlos Williams and Wallace Stevens’, Journal of Modern Literature, 1984

[19] Ibid

[20] Martin Dodsworth, ed., The Survival of Poetry, p.37

[21]'Interview: Moroccan-born Israeli poet Mois Benarroch', memoria y migracion, July 15 2010

[22] John O’Loughlin, Abstracts, Introduction (unnumbered pages)

[23] Pablo García quoting Parra in ‘Contrafigura de Nicanor Parra’, Atena, Jan/Feb 1955, p.157

have never quite forgiven him. Was that wise? Well it worked out okay in the long run but it might have ended his career. When Jerry Lee Lewis married his thirteen-year-old third cousin twice removed that didn’t exactly go down so well with his fans.

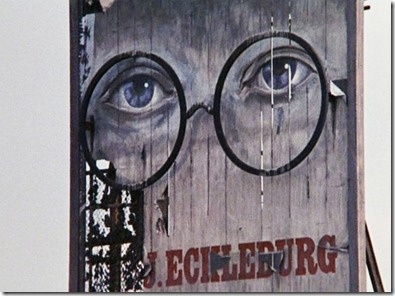

have never quite forgiven him. Was that wise? Well it worked out okay in the long run but it might have ended his career. When Jerry Lee Lewis married his thirteen-year-old third cousin twice removed that didn’t exactly go down so well with his fans. film with Michael Douglas, Falling Down. What happens when a reasonable man gets pushed too far? By 1989 I had been ‘reasonable’ for thirty years. The eyes, of course, are the windows of the soul. My body was still going through the motions of being good, being reasonable, but inside I was heading for a breakdown and a few short years afterwards it came.

film with Michael Douglas, Falling Down. What happens when a reasonable man gets pushed too far? By 1989 I had been ‘reasonable’ for thirty years. The eyes, of course, are the windows of the soul. My body was still going through the motions of being good, being reasonable, but inside I was heading for a breakdown and a few short years afterwards it came.

Bottom line, would I recommend this book? Absolutely. As long as you know what you're getting into. The simple fact is I was smiling by the end of the first page and I continued to smile throughout the book. Is it an easy read? Yes and no. You could rush through this book and get the gist but the whole point of a book like this is to stroll through it like any of the residents wandering up Tilling High Street on the lookout for some juicy gossip. If you tread carefully you will be rewarded.

Bottom line, would I recommend this book? Absolutely. As long as you know what you're getting into. The simple fact is I was smiling by the end of the first page and I continued to smile throughout the book. Is it an easy read? Yes and no. You could rush through this book and get the gist but the whole point of a book like this is to stroll through it like any of the residents wandering up Tilling High Street on the lookout for some juicy gossip. If you tread carefully you will be rewarded.

![Kadare_Ghost_Rider[4] Kadare_Ghost_Rider[4]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/-41Mg20NurzE/UDJN3GgLO8I/AAAAAAAAFi8/11e2HhlaKdA/Kadare_Ghost_Rider%25255B4%25255D_thumb.jpg?imgmax=800)

Mois Benarroch

Mois Benarroch