I like your Christ, I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ – Mahatma Gandhi

Justice is a good idea; lawyers not so much. Politics is a good idea; governments not so much. Beliefs are a good idea; religions, again, not so much. The world is full of good ideas but as soon as we draft people in to manage them everything goes pear shaped. Regular readers of this blog may have noticed that I never discuss religion. It seems, though, as I’m going to review a book called Mormon Diaries, I should at least say where I stand when it comes to religion: I don’t care. I’m not a true believer, a lapsed anything, an agnostic or an atheist. I am not interested in discussing the issues. I do not want to be converted nor am I interested in converting others to my mindset. I … don’t … care.

I was not always that way. I was raised by a pair of devout fundamentalist Christians and that upbringing had a lot to do with who I am today; I am a principled and dutiful person. As far as religions go I liked that mine encouraged an inquiring mind—there was none of this “it’s a mystery” or “because we say it’s true”—and I appreciated that but an intellectual grasp of scripture can only take one so far. At a fairly young age I realised that there was something amiss but I kept going through the motions assuming that by osmosis I would eventually discover or develop my spiritual side. I never did and fifteen years ago I stopped pretending to myself and resigned formally. There are people who have no sense of smell. I have no spiritual awareness. Nada. My decision did not go down well with my family. The last time I spoke to my siblings was at our mother’s funeral and I have had no contact with them since and that’s over ten years. So if I approached Mormon Diaries from a sympathetic standpoint you’ll understand why.

There is an old Jesuit maxim "Give me a child for his first seven years and I'll give you the man." It’s been co-opted by everyone, even Lenin. Roman Catholics will understand this better than most because they have their own special brand of guilt that never goes away. The principle is certainly a biblical one: "Train up a boy according to the way for him; even when he grows old he will not turn aside from it." (Proverbs 22:6) The modern word for it is indoctrination. Classic conditioning is usually done by pairing two stimuli, as in Pavlov’s experiments with dogs, and it comes in two flavours: carrot and stick. The reward is joining the choir invisiblewhen you die or attaining Nirvana or living forever on a paradise earth; the punishment is going to the big bad fire, missing out on the Rapture or coming back as a cockroach or something equally repugnant. Of course there are lots of wee rewards and punishments on the way (Freemasons have ninety different degrees from apprentice to grand master) but every creed has these two biggies: life vs. death. Some religions wave the big stick more than others but I don’t know of any faith that doesn’t use threats or promises to corral its members.

There have been many books written about people who have been brought up in a religion, sect or cult and then had difficulty leaving. We hear of people needing to be deprogrammed and the like and it all sounds very scary. We associate such stories with things like the Waco siege where some 72 members of the Branch Davidianreligious sect died in a fire; the mass suicide of 39 members of Heaven’s Gate, a UFO religion and the murders and suicides carried out by the Order of the Solar Temple. Surely there’s no comparison between these groups and an organisation with millions of members? There are over three million Moonies, seven million Jehovah’s Witnesses, anywhere from eight million to fifteen million Scientologists, fourteen million Mormons and sixteen million Seventh Day Adventists if you believe their press. Could we really say a film or a novel had a cult following if even three million people had seen or read it? The issue here is not to look for a label because the world’s major orthodox religions can be every bit as guilty as the newer ones when it comes to treating their members unfairly.

One of the first books I heard of which talked about how hard it can be to move on dates back to 1956: Thirty Years a Watchtower Slave. I doubt many will have heard of that but what about Oranges are Not the Only Fruit in which Jeanette Winterson presents a fictional accounts of her life among working-class evangelists in the North of England in the 1960's and the problems she faced when she realised she was gay? Steven Hassan discusses his time in the Unification Church in Combating Cult Mind Control and what about Nancy Many’s My Billion Year Contract, Memoir of a Former Scientologist? Sophia L. Stone’s Mormon Diaries joins the back of a long queue.

So what do you know about Mormonism? Before I sat down to read this book I made a list:

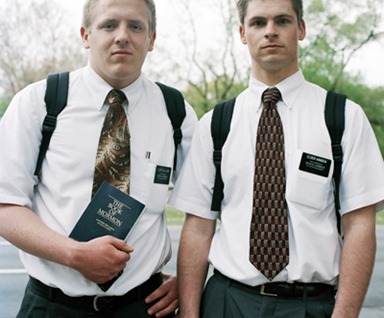

- They practice door-to-door preaching. Here in the UK we usually open the door to two smartly-dressed young “elders” who are on a tour of duty and once they’re done with it they don’t go door-to-door again.

- They are Christians but in addition to the Bible they believe that the Book of Mormon is also part of sacred scripture. Not sure where The Pearl of Great Price fits in.

- I knew they used to practice polygamy—Mormon fundamentalists still do apparently.

- Their churches are called temples.

- Disfellowshipping and excommunication are not the same thing and neither is as severe as disfellowshipping (if you’re a Jehovah’s Witness) or excommunication (if you’re a Catholic). Also they don’t officially shun like the Amish, the Scientologists (who call it ‘disconnection’) or the Witnesses.

That was my lot I’m afraid. My wife knew a few other things which I should have remembered (like not drinking tea or coffee) but she was no expert either.

One of the problems reading science fiction is the fact that the author often has to present and explain a completely different world to the one we live it. Lots of exposition ensures. Take a book like Dune with a least two hundred unique terms like Fremen, face dancers, gholas, the Imperium, melange, no-chambers, sandworms and thumpers. Or what about Nadsat, the fictional argot (that’s a secret language) used in A Clockwork Orange? That’s what reading Mormon Diaries feels like at times. I draw the comparison with science fiction deliberately because Mormonism will be, for the majority of us, an alien world involving testimonies, the baptism of the dead, endowments, exaltations, tithing, missions, polyandry, stakes, the restored gospel and various quorums. Even a simple word like ‘teacher’ means something different. From the book’s glossary:

Teacher: A fourteen or fifteen year old boy with the Aaronic Priesthood, capable of passing and preparing the sacrament, collecting fast offering, and home teaching.

Of course we then need to understand what ‘Aaronic Priesthood’, ‘the sacrament’, ‘fast offerings’ and ‘home teaching’ mean and involve.

Of course we then need to understand what ‘Aaronic Priesthood’, ‘the sacrament’, ‘fast offerings’ and ‘home teaching’ mean and involve.

Sophia L. Stone was born to two Mormon parents. Unlike Roman Catholics and many orthodox religions Mormons do not practice infant baptism. Mormon baptisms take place only after an "age of accountability" which they set at eight years of age and involve complete immersion. Interestingly Mormon baptism does not purport to remit any sins other than personal ones, as they don’t believe in original sin. That, of course, is a major difference between them and most other Christian denominations. So it’s fair to say that Sophia was not born a Mormon but chose to become one of her own free will. Needless to say Mormons have their own idea what free will is.

Mormon Diaries charts, for want of a better expression, her rise and fall from grace. It begins with an eight-year-old Sophia preparing for her baptism:

My journey into Mormonism began at the age of eight after I’d emerged from the waters of baptism, peeled off my soaking wet clothes, dried my hair, changed into my dry Sunday dress, and plopped into a chair located in front of the baptismal font under the anticipatory gazes of family members, friends, and neighbours.

I bowed my head. A circle of men gathered around me. The bishop, my dad, and a number of my father’s friends stood so close as they put their hands on my head that it felt like being in a fort made of arms and shoulders and torsos. I felt small and important at once, eager to have The Gift of the Holy Ghost.

It was the moment I’d been waiting for. The monumental occasion when the bishop would call me by my full name, use the Priesthood to call upon the powers of heaven, and pour into my heart and mind a peacefulness akin to nothing I’d ever experienced before.

[…]

I’d wanted to feel the Holy Ghost pour into me so badly that I memorized every sound in the room: the buzzing of the lights, the ticking of the bishop’s watch, even the pregnant silence of those watching. I memorized the weight of the hands on my head, the lack of a draft as I sat in the blessing circle, the collective rise and fall of shoulders clad in blue and black suits as the bishop spoke. And so, when the prayer ended and I felt nothing but the air around me, I convinced myself I’d felt something the same way a child who believes in Santa runs through the house on Christmas Eve announcing they’ve seen flying reindeer.

I stood and said, “I feel it!”

But in the moments that followed, when people were shaking my hand and there was no time for confession, regret washed over me.

I had lied.

“No virtue ever was founded on a lie.” – Dinah Craik. I don’t know Sophia very well. She comes across as a virtuous person and that’s not surprising because she was brought up by two devout Mormons. She was taught to be modest, not to swear, to avoid silliness (and she admits to being a serious young girl even at eight), to respect her parents and not to tell fibs. When people say there’s good in all religions the fact is that that’s true. As I said I am the man I am today—the good bits and the bad—because of how I was bought up.

“No virtue ever was founded on a lie.” – Dinah Craik. I don’t know Sophia very well. She comes across as a virtuous person and that’s not surprising because she was brought up by two devout Mormons. She was taught to be modest, not to swear, to avoid silliness (and she admits to being a serious young girl even at eight), to respect her parents and not to tell fibs. When people say there’s good in all religions the fact is that that’s true. As I said I am the man I am today—the good bits and the bad—because of how I was bought up.

After her baptism and confirmation Sophia sat in Fast and Testimony Meeting along with others from her church:

Many of them told stories about their family, some recounted experiences when they’d felt the spirit. But when one man in particular spoke about my baptism and confirmation, saying how my countenance had glowed when I stood and said, “I feel it!” my stomach twisted with guilt.

“I didn’t really feel anything,” I whispered to my dad. “Should I go up and tell everyone the truth?”

I’d been taught all my life to be honest, and my impulse to go up to the pulpit and confess my sin was almost unbearable. I could, in fact, think of nothing more important than correcting the lie I’d told.

My father, however, knew people better than I did. He knew perfectly well what was appropriate in a Sunday service. He knew what I did not, that there’d been conflict amongst some in the congregation over what kinds of stories were appropriate to tell in church. So while I had no idea what was going through his mind at that moment, I’m sure what he said next was his way of looking out for me.

“Don’t do that, sweetheart. You wouldn’t want to hurt anyone’s testimony.”

There is nothing in the book to say that this matter was discussed any further once they got home or in the days that followed. She was an official member of the LDS church (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) and she fell into step. She rationalises away her doubts

Maybe God simply didn’t want me to feel his spirit pour into me, maybe he wanted me to live like I knew the church was true, act like I knew, talk like I knew, and continue to read the scriptures and pray until I finally did know.

and got on with the day-to-day business of being a Mormon which was not always so easy. For starters she went to a public school. I had expected her to talk about being ostracised or picked on because of her beliefs but it looks like her poor academic performance saved her from that and that was what the kids focused on:

I couldn’t get my homework done. Couldn’t remember half the stuff I read. Couldn’t pass a test to save my soul. And Mrs. Anderson took each failure personally, attributing my poor performance first to laziness and then to passive-aggressive defiance. The more I struggled to complete and turn in my homework, the more she tried to motivate me by taking away class recess time. Not just mine, but everyone else’s.

When I finally started completing assignments, my reputation was damaged beyond repair. My classmates had stuck a label on me that simply wouldn’t come off. I sat alone each afternoon in the cafeteria, kept my eyes perpetually down, and would sometimes cry as I walked home from school.

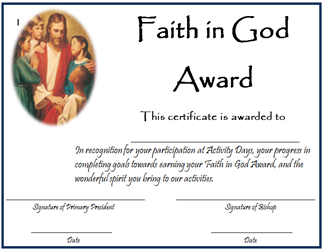

So what does she do? She immerses herself in her church activities. A journal entry from January 4th 1987 reads:

Today we went to church at 11:30 a.m. I went to my Merry Miss class and found out many wonderful things. We are going to try to do Faith in God Awards. You set a goal in a certain area. We do the goal for two months.

After you’re done, you get a necklace with the scriptures and the angel Moroni on them. It’s painted gold and comes in its own case. I’m so excited. I have so many wonderful things to be proud of, and one reason I think I’m able to do these things is because I probably earned them, because you earn happiness. And this is happiness.

Her story goes on through college and marriage and the birth of her four children. She was never in any doubt what the future held out for her:

My father had made my purpose clear at my baby blessing when he’d put his hands on my head and prayed I’d never choose a career over the important full-time work of nurturing my kids and future husband. I may have had no memory of that event, but I still knew the gist of what he’d said because it was written in my pale pink baby book mere pages from my name and date of birth: Sophia White, born April 30, 1976.

She has lived a regimented, rule-based life:

1. Thou shalt keep the Sabbath day holy.

2. Thou shalt not drink coffee or tea.

3. Thou shalt love God.

I have to ask: Since when was abstaining from caffeine more important than loving God which Jesus said was the greatest commandment?

4. Thou shalt read your scriptures daily.

5. Thou shalt give 10% of thy income to the church.

6. Thou shalt fast once a month.

Apart from the tea and coffee thing these are all the kind of things you might expect. But down the list (which contains sixty entries) there are a few that make one wonder a little:

29. Thou shalt do genealogy.

32. Thou shalt not wear flip flops to church.

36. Thou shalt avoid silliness and loud laughter.

55. Thou shalt not procrastinate.

57. Thou shalt go to the temple and perform baptisms for the dead.

but the two one needs to worry about are:

31. Thou shalt not criticize your leaders.

60. Thou shalt not doubt, ever.

And what happens if you do doubt?

If I’d openly spoken about my doubts to others, the bishop could have taken away my temple recommend, released me from my calling, and forbidden me from taking the sacrament of bread and water until my repentance was complete. He’d likely see his actions as a form of mercy. For no unclean thing can enter the presence of God. He might even see it as a way of protecting me, which would make total sense if my Heavenly Father valued worthiness above all else.

Here’s a case in point: King Saul. Saul wasn’t a bad lad. When he was told that God has chosen him to be king he went away and hid. So this was a man handpicked by the sovereign of the universe and yet by the end of his forty year rule he was nothing less than an apostate: he’d instituted false worship, attempted murder, consulted with the witch of Endor and was generally stubborn and egotistical. Who says that leaders are beyond criticism?

Here’s a case in point: King Saul. Saul wasn’t a bad lad. When he was told that God has chosen him to be king he went away and hid. So this was a man handpicked by the sovereign of the universe and yet by the end of his forty year rule he was nothing less than an apostate: he’d instituted false worship, attempted murder, consulted with the witch of Endor and was generally stubborn and egotistical. Who says that leaders are beyond criticism?

As far as doubt goes we need look no further than poor old Doubting Thomas whom the Catholics have now venerated. Saint Thomas didn’t just doubt anyone either: he doubted the resurrected Messiah to his face. All the guy wanted was proof. He got his proof—thank you very much—and then he went right back to believing.

Doubt doesn’t come as easily as one might imagine. Belief is a habit—some might even go so far as to call it an addiction—and we all know how hard it can be giving up a habit. My father sucked on an empty pipe for years after he gave up smoking and even after the bowl got broken (probably by me—I was a destructive wee bugger from all accounts) he still sucked on the stem for a long while after that.

For the most part Sophia did not have any problems with her faith. She believed in God. She believed there could only be one true religion. She trusted her husband and the church leaders. And then something started bothering her: the role of women in the Christian congregation. At a Sunday School Class they decide to discuss Ephesians 5:22-24:

Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church: and he is the saviour of the body. Therefore as the church is subject unto Christ, so let the wives be to their own husbands in everything. — Ephesians 5:22-24

“I prefer what they say in the temple, because the word ‘as’ has more than one meaning, and when we’re told to hearken to our husbands as he hearkens to the Lord, I take that to mean I’m only under covenant to follow my husband when he follows God.”

“So you’re his judge,” my Sunday School teacher said. Well, now he’d twisted my words around to make my interpretation sound unfair.

“No, I don’t think ‘judge’ is the right label. Let’s say a woman has a husband who hits her. I think it’s safe to say he’s not harkening unto the Lord and that the wife is no longer under any obligation to be submissive to her husband.”

“So you’re his judge,” the teacher repeated.

I knew a losing battle when I saw one. “It’s the responsibility of every self-respecting woman to judge her husband,” I quipped.

A few people laughed, and the woman behind me poked me in the shoulder and gave me two thumbs up. I allowed myself to feel optimistic about where the lesson was going.

That was my first mistake.

For the next twenty minutes, I listened to the teacher explain how a man is more likely to treat his wife with respect and love when he understands that the temple covenants essentially make him a God to his wife.

Of course this is all nothing new to me. My dad declaimed on more than one occasion, “In this house I am God.” This, however, is the thin edge of the wedge for Sophia and over the next few chapters we witness her slowly losing her faith. Not, I should make clear, her belief in God but her belief in Mormonism. And you can only imagine the trouble that causes when that finally became public knowledge. Or perhaps you can’t. I honestly expect that most people will have no idea what Sophia was going to have to go through. And that’s why books like this are necessary.

It’s not the longest or most in-depth book you will read on this subject. It’s obviously written by a nice lady who really doesn’t want to hurt, upset or offend anyone and yet in all good conscience can’t stay silent. She even uses a pseudonym so as not to do anything that might damage her family. She’s not an angry, bitter or vindictive person. She says:

On my bad days, I feel more disappointment than anger. Mostly because I believed with all my heart the promises found in Mormonism. I thought I was happier than other people, that I had greater access to spirituality, that I knew my most important and fulfilling role. I believed I had divine knowledge and purpose. Now I’ve found that many of these promises are smoke and mirrors.

And I’m further disheartened when I see religion hurt families. You’d think a family centred church would shout from the rooftops not to shun family members who’ve fallen away. You’d think they’d allow non-believing parents to see their believing kids get married in the temple. You’d think they’d support all different kinds of families, not just those that meet one definition. But all too often an ideal is promoted that benefits the church over families that are struggling. “Traditional gender roles” and “conservative family values” are taught as religious principles.

I asked her who this book was aimed at.

Anyone who wants to better understand how religions indoctrinate children, how they can unite and separate families, how they can bring peace and turmoil at the same time. Anyone who wants a more personal understanding of how it feels to grow up in a legalistic religion that values trust and obedience more highly than free thought, or anyone who wants to understand Mormonism.

Please don’t misread that to mean my book is factually perfect. It’s not. It is based on my experience, and everyone’s reality is different. But I stand by my claim that people who leave Mormonism are often in an isolating place. It’s hard for an orthodox believer to understand why anyone would leave. It’s hard for those who’ve never been in a fundamentalist religion to understand why leaving one is such a big deal. To both these groups, I’d say, “Please read this!” Understanding is vital.

I don’t think anyone who has not been brought up in a fundamentalist organisation—be it a religion, a cult, a sect or even a political party—will in fact understand. You can’t possibly understand unless you’ve been there. I read recently someone’s opinion “that Mormonism isn’t just a religion, it’s a culture.” I think that’s well put. Imagine packing your bags and leaving for India or China or Mars. Imagine the culture shock. The same article goes on:

As members of the LDS church take their first steps into traditional, Biblical Christianity, they are often accosted by sights, sounds, and

philosophies which (at times) differ greatly from those with which they are familiar. Wading through the positive and negative aspects of LDS culture and its relationship to the Truth frequently leaves these new believers feeling as though they are “immigrants in a foreign land”.

Or as Heinlein (and the King James Version) might put it: strangers in a strange land.

Most people I associate with these days haven’t the slightest interest in religion. Many, like me, had religious upbringings and yet even in their fifties, sixties and seventies cannot shake off completely what they were taught as children. ‘Sophia’ will never be free. Not even if she moves to Mars.