Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them – William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night

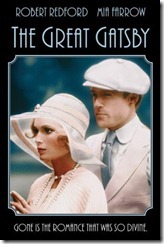

Modern Library lists The Great Gatsby as the second-best English-language novel of the twentieth century, being pipped to the post by Ulysses in case you wondered. In its European equivalent, Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century, the book only comes in it at No. 46; Steinbeck’sThe Grapes of Wrath (which reaches the dizzying heights of No. 7) being the top-ranking English-language novel. Coincidentally, both Steinbeck’s novel and Fitzgerald’s are books that have at one time or other—and continue to be—referred to as examples of the “Great American Novel.”The Great Gatsby has been adapted for the cinema four times (with a fifth due out in 2013) but, of course, that pales into insignificance when compared to Jane Eyre’stwenty-one times. Leonardo DiCaprio will be playing the title role of Jay Gatsby (you can see the trailer here) and I’m sure he’ll do a good job but he’s no Robert Redford (you can see the trailer for the 1974 adaptation here) although I’m not sure either was or will be Jay Gatsby.

The book has also been given a makeover by Alma Classics (the new name of Oneworld Classics)—“[t]he spelling and punctuation have been anglicised, standardised, modernised and made consistent throughout.” They offered me my pick of all four of Fitzgerald’s novels which they have just reissued with rather lovely foil embossed covers, French flaps and extensive notes. Needless to say I plumped for the shortest but mainly because of its reputation and the fact I’d never read anything by him so that seemed like the place to start. Coincidentally I’d never seen any of the film adaptations either, not even the TV adaptation from 2000 which starred Toby Stephens who—small world—has also played Edward Rochester in another TV adaptation of Jane Eyre.

The book has also been given a makeover by Alma Classics (the new name of Oneworld Classics)—“[t]he spelling and punctuation have been anglicised, standardised, modernised and made consistent throughout.” They offered me my pick of all four of Fitzgerald’s novels which they have just reissued with rather lovely foil embossed covers, French flaps and extensive notes. Needless to say I plumped for the shortest but mainly because of its reputation and the fact I’d never read anything by him so that seemed like the place to start. Coincidentally I’d never seen any of the film adaptations either, not even the TV adaptation from 2000 which starred Toby Stephens who—small world—has also played Edward Rochester in another TV adaptation of Jane Eyre.

I had no expectations. I didn’t even know it was a love story. Which it is. Of sorts.

In her book Pseudoautobiography and Personal Metaphor Millicent Bell writes: "All fiction is autobiography, no matter how remote from the author's experience the tale seems to be." I don’t see how F. Scott Fitzgerald could argue with that and it’s obvious that he was drawing from personal experiences when he laid out this tale. Where it is more than simply a rehashing of past events is where Fitzgerald chooses to change history and look at how things might have panned out if his life had taken a different course. Neither Gatsby nor Fitzgerald had the best start in life; they both fail to do well academically, although when they enlist towards the end of World War I they move up in the ranks quickly enough; they struggle to make much of themselves when demobbed and because of this they each fail to win the hand of the woman they love. The difference is that Zelda waited for Fitzgerald to find his feet; Daisy does not and opts to marry the rich Tom Buchanan instead. So in The Great Gatsby we are faced with a what-if scenario.

Of course the great thing about novels from an autobiographical point of view is that you can divvy yourself up between the characters. The novel’s narrator, Nick Carraway, is a young man from Minnesota who, after being educated at Yale and fighting in World War I, goes to New York City to learn the bond business. Fitzgerald was born in Minnesota, spent his early years in New York, was educated at Princeton, fought in the war and worked for a spell in advertising.

So who exactly is this Gatsby? That is a very good question and Fitzgerald is in no rush to tell us. Everyone has their opinion, though. What is not in doubt is that he lives in a massive house—“a factual imitation of some Hôtel de Ville in Normandy”—in West Egg (in reality the Village of Kings Point, Great Neck, Long Island) which is the poor cousin to East Egg across the bay (the next peninsula over on Long Island Sound) where all the really posh people live. Gatsby is not posh. He is rich but those who live in East Egg come from old money and there’s the difference. Gatsby is a parvenu and where was a fast buck to be made between 1920 and 1933? Bootlegging and racketeering amongst other things. Not that he is in a rush to open up to anyone and we never do know for sure what businesses he has been in. We do know that he regularly hosts lavish parties which are attended by anyone who chooses to turn up with a mind to having a good time

People were not invited—they went there. They got into automobiles which bore them out to Long Island and somehow they ended up at Gatsby’s door. Once there they were introduced by somebody who knew Gatsby and after that they conducted themselves according to the rules of behaviour associated with amusement parks. Sometimes they came and went without having met Gatsby at all, came for the party with a simplicity of heart that was its own ticket of admission.

but he’s rarely seen at any of these which leads to speculation:

‘Well, they say he’s a nephew or a cousin of Kaiser Wilhelm’s. That’s where all his money comes from.’

[…]

Somebody told me they thought he killed a man once.’

A thrill passed over all of us. The three Mr. Mumbles bent forward and listened eagerly.

‘I don’t think it’s so much THAT,’ argued Lucille sceptically; ‘it’s more that he was a German spy during the war.’

One of the men nodded in confirmation.

‘I heard that from a man who knew all about him, grew up with him in Germany,’ he assured us positively.

‘Oh, no,’ said the first girl, ‘it couldn’t be that, because he was in the American army during the war.’ As our credulity switched back to her she leaned forward with enthusiasm.

‘You look at him sometimes when he thinks nobody’s looking at him. I’ll bet he killed a man.’

The book is written from Carraway’s perspective two years after the events in the novel. So he’s had time to reflect on those events and weigh his words carefully. Eventually he gets to learn much of the truth but not all and certainly not from Gatsby whose fabrications have taken on a life of their own. Looking back Carraway has this to say about Gatsby:

Conduct may be founded on the hard rock or the wet marshes but after a certain point I don’t care what it’s founded on. When I came back from the East last autumn I felt that I wanted the world to be in uniform and at a sort of moral attention forever; I wanted no more riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart. Only Gatsby, the man who gives his name to this book, was exempt from my reaction—Gatsby who represented

everything for which I have an unaffected scorn. If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life, as if he were related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away. This responsiveness had nothing to do with that flabby impressionability which is dignified under the name of the ‘creative temperament’— it was an extraordinary gift for hope, a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person and which it is not likely I shall ever find again. No—Gatsby turned out all right at the end; it is what preyed on Gatsby, what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreams that temporarily closed out my interest in the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men.

It is a paragraph that bears rereading since by the time the book has ended Carraway certainly seems to be Gatsby’s only true friend. As long as he’s been around to fund their indulgences everyone was interested in being Gatsby’s friend even if he wasn’t much interested in being seen with his newfound (and fair weather) friends. Caraway, unlike his neighbours, doesn’t crash any of Gatsby’s parties. Intrigued as he is with the man, he waits until he is invited. But meeting him does little to assuage his curiosity; if anything the reverse is true: the man is an enigma but only up to a point; spend enough time in his company (which Carraway begins to) and the cracks in his character start to appear. As Jim says to Huckleberry Finn: "It's too good for true, honey, it's too good for true." Everyone has a skeleton or two in their cupboard.

The snob in Nick Carraway looks down on Gatsby which is ironic because he’s renting a place—“a weather beaten cardboard bungalow” he calls it—for eighty bucks a month whilst surrounded on all sides by millionaires and yet his final words with Gatsby are, “You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.” Why? Because “[t]hey’re a rotten crowd.” They may have what all of Gatsby’s money could never buy him—I suppose the word for that would be ‘class’ or ‘taste’—but they are remote and out of touch with their humanity.

I said before that everyone was interested in being Gatsby’s friend. That’s not strictly true. The more reserved East Eggers keep their distance. Both suburbs are inhabited by wealthy people but when money levels the playing field people will always find some way to try to differentiate themselves from their peers. Gatsby still has to work to maintain his lifestyle—he’s always taking phone calls concerning business—whereas others, like Carraway’s second cousin Daisy, and her husband Tom (who Nick had known from college), do not. They currently live in East Egg.

Why they came east I don’t know. They had spent a year in France, for no particular reason, and then drifted here and there unrestfully wherever people played polo and were rich together. This was a permanent move, said Daisy over the telephone, but I didn’t believe it—I had no sight into Daisy’s heart but I felt that Tom would drift on forever seeking a little wistfully for the dramatic turbulence of some irrecoverable football game.

They are also why Gatsby is here. Or rather she is why Gatsby is here. He has followed her like a lovesick puppy dog. You see, Daisy and Gatsby have met before. In fact they fell in love. Her friend and bridesmaid, Jordan, tells Carraway:

That was nineteen-seventeen. By the next year I had a few beaux myself, and I began to play in tournaments, so I didn’t see Daisy very often. She went with a slightly older crowd—when she went with anyone at all. Wild rumours were circulating about her—how her mother had found her packing her bag one winter night to go to New York and say goodbye to a soldier who was going overseas. She was effectually prevented, but she wasn’t on speaking terms with her family for several weeks. After that she didn’t play around with the soldiers any more but only with a few flat-footed, short-sighted young men in town who couldn’t get into the army at all.

By the next autumn she was gay again, gay as ever. She had a debut after the Armistice, and in February she was presumably engaged to a man from New Orleans. In June she married Tom Buchanan of Chicago with more pomp and circumstance than Louisville ever knew before.

In time we discover that the soldier she had been involved with had been Gatsby. What we don’t realise is that he had fabricated the identity of Jay Gatsby along with a suitable past and that really he had nothing to offer her bar love and in Daisy’s world money trumps love every time. To have a fighting chance of winning her back Gatsby needs to rid himself of his one handicap—poverty—by fair means or foul.  Now having done so he is hesitant and befriends Carraway as a means of easing his way back into her life. That an actual friendship develops, albeit a slightly awkward one, is not so surprising because Carraway can empathise with Gatsby’s predicament. He develops a relationship with Jordan Baker but he has no money and poor prospects so what chance does he stand with her?

Now having done so he is hesitant and befriends Carraway as a means of easing his way back into her life. That an actual friendship develops, albeit a slightly awkward one, is not so surprising because Carraway can empathise with Gatsby’s predicament. He develops a relationship with Jordan Baker but he has no money and poor prospects so what chance does he stand with her?

The actual storyline that runs through the centre of The Great Gatsby is not a very complex one. It feels more involved than what it is because of the order in which Fitzgerald presents his facts. Told chronologically this would be nowhere near as compelling. The only thing that remains to be answered is: Will Gatsby be successful in winning Daisy over? Well, once we learn a bit about Tom Buchanan it looks like all he needs to do is pop the question and Daisy will run away with him without a backwards glance. At one point Daisy describes her husband as follows:

A brute of a man, a great big hulking physical specimen of a—‘

She never gets to finish her sentence. Shortly after this heated exchange with Tom he leaves the dinner table to answer a phone call. It is from “some woman in New York” he’s having an affair with. At least that’s how Jordan describes her. She’s half-right. The woman, Myrtle Wilson, is actually married to a local garage owner George Wilson who lives halfway between West Egg and New York. Daisy knows. Not the specifics. But enough. So, as I’ve said, Gatsby really doesn’t have his work cut out for him. What could possibly go wrong? Well if the point to all this was just getting his hands on the woman but it’s not and this is something Gatsby reveals unwittingly to Carraway:

He wanted nothing less of Daisy than that she should go to Tom and say: ‘I never loved you.’ After she had obliterated three years with that sentence they could decide upon the more practical measures to be taken. One of them was that, after she was free, they were to go back to Louisville and be married from her house—just as if it were five years ago.

‘And she doesn’t understand,’ he said. ‘She used to be able to understand. We’d sit for hours—’

He broke off and began to walk up and down a desolate path of fruit rinds and discarded favours and crushed flowers.

‘I wouldn’t ask too much of her,’ I ventured. ‘You can’t repeat the past.’

‘Can’t repeat the past?’ he cried incredulously. ‘Why of course you can!’

He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of his house, just out of reach of his hand.

‘I’m going to fix everything just the way it was before,’ he said, nodding determinedly. ‘She’ll see.’

He talked a lot about the past and I gathered that he wanted to recover something, some idea of himself, perhaps, that had gone into loving Daisy. His life had been confused and disordered since then, but if he could once return to a certain starting place and go over it all slowly, he could find out what that thing was….

Gatsby thinks it’s the girl he wants. It’s not. It’s what he lost when she went off with Tom. And, of course, that can never be recaptured. In some respects Gatsby is living the American dream but he’s still dreaming.

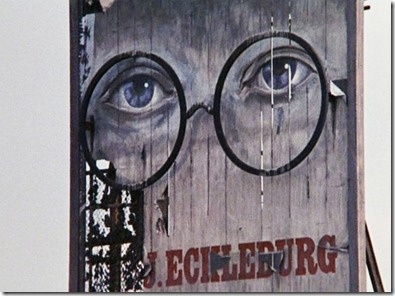

After I finished the book I located a copy of the 1974 adaptation and watched it. There is a lot good about it. Francis Ford Coppola, who wrote the screenplay which is very faithful to the novel and uses chunks of dialogue straight off the page, lived in "West Egg," aka Great Neck, former home of Fitzgerald, at the time of writing the screenplay. He was a fan but just because you get a great writer who understands and believes in the material doesn’t mean the thing is going to work on the screen. Just look at Watchmen. Could you get a more faithful adaptation? But it’s missing something. And so is this film. Coppola apparently disowned his screenplay when he saw the film, because he felt the movie adaptation ruined his work. So the problem has to be with direction and casting. Well, yes, but there is one other issue: symbolism. The Great Gatsby is a highly symbolic work. There are loads of sites devoted to its symbolism alone. Two of the most important ones are made clear in this adaptation: the green light across the bay and the billboard of T.J. Eckelburg.

After I finished the book I located a copy of the 1974 adaptation and watched it. There is a lot good about it. Francis Ford Coppola, who wrote the screenplay which is very faithful to the novel and uses chunks of dialogue straight off the page, lived in "West Egg," aka Great Neck, former home of Fitzgerald, at the time of writing the screenplay. He was a fan but just because you get a great writer who understands and believes in the material doesn’t mean the thing is going to work on the screen. Just look at Watchmen. Could you get a more faithful adaptation? But it’s missing something. And so is this film. Coppola apparently disowned his screenplay when he saw the film, because he felt the movie adaptation ruined his work. So the problem has to be with direction and casting. Well, yes, but there is one other issue: symbolism. The Great Gatsby is a highly symbolic work. There are loads of sites devoted to its symbolism alone. Two of the most important ones are made clear in this adaptation: the green light across the bay and the billboard of T.J. Eckelburg.

When Carraway sees Gatsby for the first time they are standing outside at night and Gatsby is looking out across the bay:

I didn’t call to him for he gave a sudden intimation that he was content to be alone—he stretched out his arms toward the dark water in a curious way, and far as I was from him I could have sworn he was trembling. Involuntarily I glanced seaward—and distinguished nothing except a single green light, minute and far away, that might have been the end of a dock.

Only on the last page of the book do we get Fitzgerald’s explanation for what the light represents:

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – to-morrow we will run farther, stretch out our arms farther….

Redford does reach out and try and grasp something intangible but had I not read the book I would have wondered what he was doing. It looked, frankly, a bit silly and exaggerated, the kind of thing a silent actor would have done. The word ‘orgastic’ was coined by Fitzgerald, by the way. It is most likely a cross between ‘orgasmic’ and ‘orgiastic’, although it is certainly left open to interpretation.

Now to the billboard:

[A]bove the grey land and the spasms of bleak dust which drift endlessly over it, you perceive, after a moment, the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg. The eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a nonexistent nose … But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.

The billboard I did like; I had not fully appreciated its significance when reading the book. It reminded me of the images of Big Brother in Nineteen Eighty-Four. But this is not a totalitarian state. This is a capitalist country, the most capitalist of countries. So who is overseeing all of this? Not God surely? Or maybe. When George takes Myrtle to the window and tells her she can’t fool God he’s using the billboard as a visual metaphor. There is no Big Brother—merely a poster—and there is no God—merely a poster. God has abandoned America to its own devices. The billboard—a symbol perhaps of America’s abandoned spirituality—stands neglected staring out over and equally neglected landscape, what Fitzgerald describes as a “valley of ashes” which it is, literally, but also metaphorically. What is noteworthy about George Wilson is that he doesn’t attend church—not since his marriage there—and yet he still has a fundamental belief in a higher power.

These are just two of the images. There are others; colours in particular (yellow and especially gold, green, white and grey). Rarely is Fitzgerald only saying the one thing. This is a book about the American Dream. We all know what people mean when they talk about it but it’s really very badly named when you think about what dreams are like. Gatsby is chasing something intangible, trying to grasp light particles in his hand. At his core he really is a terribly naïve man. Of course neither Daisy nor Tom is happy either; they’re—to paraphrase Huxley—overcompensating for misery. As long as they’re having fun they don’t have to think about whether they’re truly happy or not.

Of course I’ve not told you how the book ends. You’ll have guessed that it’s unhappily—that’s a foregone conclusion I’m afraid—but the ending was a brilliant choice by Fitzgerald. It’s hard really sitting here trying to review a book that is considered by many to be the greatest American novel ever written. Of course it’s worth reading. But I knew from the first couple of pages that this was a superior piece of work. It manages what many literary novels fail to achieve, it’s also a damn good read.

The book is out of copyright and you can download a copy now if you just want the text. That’s not why anyone would buy this book from Alma. They’ll be buying it because it looks nice in fact these four novels would be a lovely present for anyone who appreciates good literature.