[I]t’s the nakedness that poetry implies that cancels it out as a respectable creative option. In an increasingly inarticulate world that communicates in cliché & jargon, there is no place for what is interpreted as promiscuous self-exposure on the part of the poet. If the poem puzzles, resentment is caused: what is the poet trying to slip past me? If the poem communicates, embarrassment results: why are you trying to share your vulnerability with me? What do you want? — Dick Jones, blog post, October 21, 2007

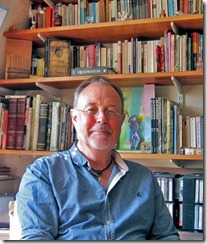

I have known Dick Jones for five years. I’ve never met him or had a face to face conversation or anything but I have got to know him nevertheless. His was, I think, if not the first, then one of the very first blogs I started following after I myself began blogging in August 2007 and I have read every one since then. In many respects Dick and I are very different people—not that a prerequisite for a long-lasting friendship ought to be how similar two individuals are—but there is definitely common ground there. For starters we both waited a painfully long time before we got round to publishing full collections of our poetry.

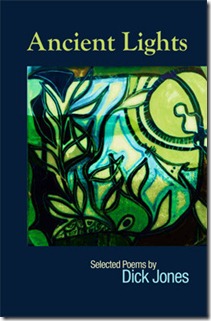

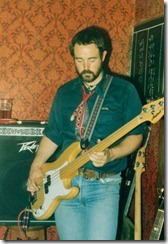

Dick is a few years older than I am. He was born on Christmas Day in the final year of World War II and a number of his poems look back to that time which is not that surprising because evidence of that war would have been everywhere during his formative years and despite people on the one hand wanting to forget all that had happened and press on with their lives they would nevertheless have felt the need for a long time to get the war out of their systems. There are also poems that celebrate  his new family—he is the father of three young children (Maisie, Rosie and Reuben) whose photos and exploits often grace his blog (we don’t hear so much about his grownup children Lindsay and Zoë)—and then there is everything in between and there has been a lot in between. He’s been a teacher—Primary, English and then drama for thirty-five years—but has also played in a variety of bands—in 1969 he discussed with David Bowie the possibility of forming a group featuring poetry and drama alongside music which never came to pass; he also once auditioned Elvis Costello as a keyboard player for his band but turned him down in favour of someone called Sparky Harris—although I would imagine the highlight of that career might rightly be playing to a capacity audience in the Albert Hall. His most prized possession is a Washburn acoustic bass guitar. He’s been a radio ham and political activist and continues to be a bibliophile (he owns thousands of books) as well as a supporter—“against all reason” (his words, not mine, but it shows that no one’s perfect)—of Watford Football Club. It is difficult to review his poetry collection Ancient Lights objectively since I’m privy to much of the background information, in fact in preparation for this article I reread many of his posts from his current blog Dick Jones’ Patteran Pages—which although he’s talked about packing in for years he’s never quite managed to—and also his old Salon Poets blog which is still accessible through Wayback Machine.

his new family—he is the father of three young children (Maisie, Rosie and Reuben) whose photos and exploits often grace his blog (we don’t hear so much about his grownup children Lindsay and Zoë)—and then there is everything in between and there has been a lot in between. He’s been a teacher—Primary, English and then drama for thirty-five years—but has also played in a variety of bands—in 1969 he discussed with David Bowie the possibility of forming a group featuring poetry and drama alongside music which never came to pass; he also once auditioned Elvis Costello as a keyboard player for his band but turned him down in favour of someone called Sparky Harris—although I would imagine the highlight of that career might rightly be playing to a capacity audience in the Albert Hall. His most prized possession is a Washburn acoustic bass guitar. He’s been a radio ham and political activist and continues to be a bibliophile (he owns thousands of books) as well as a supporter—“against all reason” (his words, not mine, but it shows that no one’s perfect)—of Watford Football Club. It is difficult to review his poetry collection Ancient Lights objectively since I’m privy to much of the background information, in fact in preparation for this article I reread many of his posts from his current blog Dick Jones’ Patteran Pages—which although he’s talked about packing in for years he’s never quite managed to—and also his old Salon Poets blog which is still accessible through Wayback Machine.

Dick and I came to poetry the same way, through the First World War poets which were a part of our respective English syllabi. He writes:

I was never forced to memorise a poem. But the first poem I went out of my way to learn by heart was Rupert Brooke’sThe Soldier. I was 15 & in the first throes of my epiphanic discovery of the First World War poets. I graduated swiftly to Siegfried Sassoon& Wilfred Owen& then to writing my own Great War verse. I have preserved the small blue notebook in which all of these early efforts are contained to remind myself always of just how utterly frightful juvenilia can be. – blog entry, December 19, 2006

By coincidence my poems from that time are also in a blue notebook which contains similar examples of highly derivative (and equally frightful) antiwar poetry. There is other common ground from that time—Larkin and R.S. Thomas (we both list ‘On The Farm’ as a favourite poem and he thinks “that concluding line from ‘An Arundel Tomb’ is probably the finest clincher of any poem”)—but then Dick was wooed by the Beats and I the Imagists (both American schools) and we found our own paths which we’ve each meandered along not trying especially hard to get anywhere with our poetry (life getting in the way and all that) until the Internet became an inescapable part of our lives.

Put it this way: neither of us became English professors or expects to be the next poet laureate. Dick writes:

If I was driven excessively from the start by the desire to set the world alight with my deathless prose or my incandescent verse, that imperative ran out of momentum when I realised that all was vanity & I was only reaching a constituency of one & even he was losing interest in my prodigious output. So I stopped & played bass guitar in a series of bands instead. – blog entry, May 20, 2007

Poetry could well have been a phase we both went through. One of the reasons Dick surmises that people these days don’t read poetry is that it reminds them of a time long past when they, too, once dabbled:

[F]or so many people … there is a deeper unease, a half-memory, maybe, of a time in life when the romantic muse pursued even the most prosaic of them with uninhibited energy. Can there be many of us who haven’t at some time in youth sat down & scribbled off a heartbroken threnody to a lost love? And then, to demonstrate the cosmic scale of heartbreak, shown it to a few close friends. And then basked briefly in the melancholy glory that attends, not the callow infatuated adolescent but the wounded artist. Time (two weeks, three weeks) heals the injury & the verses end up in the back of a drawer, returning maybe years later to haunt the author with memories of a time of chilling vulnerability. – blog post, October 21, 2007

In time we did become better poets though because despite all the other distractions that life threw at us the poetry refused to go away. We shrugged off our early romantic notions of prosody and realised that it was simply a tool that was at our disposal. Dick puts it very well when he says:

I would venture that for the majority of jobbing poets art is a minor element in the mix & craft is most of what the process is about. The raw materials are already in place: on the page, on the screen, in our ears, in our mouths. The poet stands quietly on corners plucking them as they emerge then carrying them away to push them laboriously about the page in search of a resonant image, a potent phrase.

All of which is done dispassionately, thoughtfully. The coolness & detachment of the poet pushing & tugging at the stack of words are in direct inverse proportion to the intensity of passion he or she is trying to capture & communicate. Chewed pens, strangled cries, tearstained pages are not significators of the process of emergence of a poem on its way towards greatness. In order to establish the timelessly universal from the minutely particular, the poet must work like an architect, building a structure whose strength comes from a balance of stress & counterstress.

And that process involves a sober, controlled, patient tenacity that is a million miles away from the chest beating & hair tearing that characterises the poet of popular perception – blog post, October 21, 2007

When I was a teenager poetry came easily to me. It was bad poetry but that doesn’t take away from the fact that I was constantly on the cusp, waiting—and not very patiently at that—for the next work of genius. Now if I write a poem a month I’m content. Dick’s a bit more prolific than me but he can still go for weeks, even months, without producing a thing and then wham! In April 2008 he wrote that he was “awaiting the lifting of the inspiration embargo on new verse (nothing since January)” and then in mid-June wrote five, one after another and had a sixth on the boil. Exactly the same happened to me this year. Unlike me, though, Dick’s poems often take him an interminably long time—occasionally years—to finally settle and frequently on his blog you’ll see the appearance of a second or third draft. In April 2009, for example, he wrote of his poem ‘For Johnny the Bright Star’ (which does not appear in his new collection): “I’ve had this poem in a state of very slow—almost elephantine—gestation for three years now. In fact, it stalled a few months after I started it in the white heat of zeal.” Comments like that are commonplace and many have been “slow burners”. Of ‘Mr Moore’s Wall-Clock’ (which is the third poem in the collection) he wrote in September 2007: “This poem has been in a state of slow flux for a number of years.” The fourth draft of that poem finally appeared in March 2009 and yet that still isn’t the final version we get in Ancient Lights. The earliest version I can find online dates back to June 2004 although it will be older than that, still, I have no doubt.

How to describe Dick’s poetry? A few years back I interviewed him for my blog. You can read the whole interview here and it makes interesting reading. In it I talk about the first of his poems that I read in November 2007. It’s called ‘Fox Hunting’ and I reproduce it at the start of the post:

My first thought when I read this was that this was the kind of poem that we'd get handed out in English class at school on hard-to-read roneoed copies, the kind where we'd look at the title and groan internally: Christ! Who wants to read a poem about ruddy foxes?

And then the teacher would read it aloud—no point asking one of us because we'd ruin it—and suddenly the thing would "happen in plain air" to use Dick's expression, at least how I interpret that expression. Then she'd start to ask questions and open the poem up line by line so that when she read it again at the end of the lesson it had become something else entirely.

It was having the poetry of Owen, Larkin and Hughes amongst others broken down and reassembled like this that made poetry come alive for me. 'Fox Hunting' would have slipped in there, unnoticed, without any problem but I would have carried that last line [Night self-heals, like water] with me for years.

Over on her blog The Chocolate Interrobang Karen M manages to express herself more concisely:

He is an accomplished poet who writes from the intersecting axes of his memory and dreams and history, both his family's and his country's, especially WWII.

This is similar to something Dick wrote on his own blog three months earlier:

I've been doing some work on a series of autobiographical poems, gathered under the collective title of Ancient Lights. The aim has been to place fragmentary, sometimes dreamlike memories—some my own (amongst them the earliest I can recall), others received—into the context of their time. The difficulty is, as ever, to locate the universal in the particular & personal. – blog post, January 18, 2007

This is why Dick’s collection is worth reading. Because it doesn’t ignore the universal. Poetry is personal—there’s no way around that—but the best poems transcend the personal and find a way to not so much connect with others but to enable others to connect with parts of themselves they might have been struggling to. As Dick says: “[P]oetry is just words & words belong to everyone. All a poet does is shuffle them around on a bit of paper. And anyone can do that.” Most of us manage to express ourselves in words even if we don’t write them down but only a few have the ability to say things for other people. Dick illustrates this:

The best poetry faces up to a world of near-unmitigated savagery & it rings its bells & blows its whistles loud & clear. Our vision of the First World War as a conflict of unprecedented cruelty & stupidity was not provided principally by what passed for news media at that time but by poets. – blog post, October 3, 2006

We read the writing of those whose utterances touch us most deeply for the same three principal reasons that have enchanted readers always, each one likely to be true for each of us in varying degree:

Like me he has learned not to try and make poems happen but to simply be vigilant and respond when the ideas come. As he says in an interview over on The Storialist (if you can call one question and a long answer an interview) where he talks at length about his poem ‘In the Daubigny Chapel’ (not in this collection):

I never seek out memory consciously as some kind of goad to inspiration. I can only write in response to some jolt from without or within and long periods may pass between such events. Then a small linkage of words or a complete line will simply appear, often enough in the midst of a sequence of either focused or disconnected thinking.

And from an old Salon blog:

I work best in distinctly 'unpoetic' circumstances—on the train, caught in traffic in the car, in lessons when students are working on their own, in the john, when sitting by the fountain on the way into town... Inspiration arrives undramatically & with little in the way of accompanying spiritual or other-worldly frissons. The completion of a poem gives me the satisfaction of having laid brick on brick symmetrically & having installed a window you can look out of & a door that swings freely & shuts neatly. I can't imagine not writing. – blog post, August 30, 2004

This is illustrated well in the following excerpt from his poem ‘New Sherwood’. Dave Bonta (the editor of qarrtsiluni) quotes from it in his blurb on the back cover of Ancient Lights, saying it could well be Dick’s ars poetica:

Don’t build. Just find intact

(albeit cracked and leaky)

a house that’s there

already, one that’s rooted

firm and knows its skin;

that’s free of pain

and ghosts, with trees

and half-forgotten gardens,

mossy cold-frames, twisted

vines and sudden sundials

in the long, uncultivated

grass. Then let us blow

like puffball parachutes

in a random wind,

the achene fruit

that falls and germinates

when and where

it will.

‘New Sherwoord’ is not in this collection although Dave has published a number of poems which are:

Another way that Dick is like me is that his poetry has a limited palette. That sounds like an insult but it’s not. Not every singer has a range like Freddie Mercury (Freddie’s vocals were over a four-octave range) or needs to. Most of us manage just fine with one and a half octaves. Bruce Springsteen doesn’t have much of a range and I’ll bet Leonard Cohen can’t croak more than a fifth these days. Dick returns to the same themes over and over again in the same way that a blues musician does. The Blues is not just about a bloke waking up in the morning and finding his baby gone any more than his is all about looking back to an England that’s long gone. That said Dick’s poetry does look back a lot. It’s nostalgic but not sentimental. Nature fascinates him but there are invariably people wandering around his landscapes and you realise you’re reading more about human nature than grass and trees and foxes. The collection is well named because light is everywhere: direct, reflected, refracted, moonlight, starlight, firelight. Music is also a constant—but music in the broadest sense (although U2 do have a cameo)—and every poem presents a pleasing soundscape. As he says in another recent interview:

Another way that Dick is like me is that his poetry has a limited palette. That sounds like an insult but it’s not. Not every singer has a range like Freddie Mercury (Freddie’s vocals were over a four-octave range) or needs to. Most of us manage just fine with one and a half octaves. Bruce Springsteen doesn’t have much of a range and I’ll bet Leonard Cohen can’t croak more than a fifth these days. Dick returns to the same themes over and over again in the same way that a blues musician does. The Blues is not just about a bloke waking up in the morning and finding his baby gone any more than his is all about looking back to an England that’s long gone. That said Dick’s poetry does look back a lot. It’s nostalgic but not sentimental. Nature fascinates him but there are invariably people wandering around his landscapes and you realise you’re reading more about human nature than grass and trees and foxes. The collection is well named because light is everywhere: direct, reflected, refracted, moonlight, starlight, firelight. Music is also a constant—but music in the broadest sense (although U2 do have a cameo)—and every poem presents a pleasing soundscape. As he says in another recent interview:

[A]t the point of writing I’m acutely sensitive to the way in which the words chime and I repeat sections over and again to ensure that there’s some melodic and/or rhythmic symmetry at work. For better or worse, I always aim for a musicality within each poem and I’m very conscious of the common ground between poetry and music.

Another common theme in his work is what Dick calls “the finity of things”. He writes:

I am given, however, to deep melancholy on occasions. It’s a tendency that has been with me for as long as I can remember. Almost invariably it’s provoked by a sudden & frequently acute sense of the finite nature of all things on this foreshortened spectrum from inception to inevitable decay. Even as a young child I was drawn to literature that dealt with the finity of things—with the passage of events within a specific time frame. When re-reading favourite books—The Wind in the Willows, Peter Pan, The Hobbit, Le Morte d’Arthur—my enjoyment was always tempered by a gathering awareness of the approaching imminence of conclusion & the characters’ passage into a time & place somehow less elevated & intense.

[…]

All I know is that, although melancholy drops still in late middle age a veil through which sometimes I view the world, I wouldn’t be without its darker focus. It feeds my poetry (for better or worse), enhances my response to music &—not least—protects me against the growing trend towards vapid, mindless good cheer as a kneejerk reaction to the slightest hint of adversity in these complex & troubled times. – blog post, February 21, 2007

This is perfectly illustrated in this deceptively simple poem from Ancient Lights which first appeared in Snakeskinin a slightly different form:

ROSIE'S DANDELION

Rosie brings in the last

dandelion, carrying it closed

in a chalice of hands like

a sacrament. Stock still,

she passes a slow thumb

around its bright corolla.

It lifts its head. We are charged

with its accommodation.

It lolls loud, a solo voice

in a wine glass. By morning

its royalty is spent. The crown

is sweated hair, the stem a bledvein. Rosie cups its scrap length,

lifting it to me on a tear

for aid or explanation.

But what can I tell her

about time that I would

have her know so soon?

It’s not my favourite poem in the collection but it was the one Beth chose to read in a little video commentary she did where she talks about how long she’s known Dick and the effect his poetry has on her. It’s her first go at making a video so the production values aren’t too polished but there’s a genuineness in her delivery. I see she also plumped for the hard backed version. (Sorry, Dick. Frugal Scot here only forked out for the paperback.)

I don’t see this collection as a book that young people will get excited about any more than they will have done when they were forced to endure most of the poetry they got at school. He doesn’t write punchy poems like John Cooper Clarke talking about chop suey or Majorca or why you never see a nipple in the Daily Express. Dick is a very traditional English poet in many respects, even a little old-fashioned, but nowhere near as idealistic as Betjeman. He is a poet one needs to grow into to fully appreciate or maybe I mean grow up to appreciate.

What I do find surprising, given Dick’s loudly-proclaimed atheism are the frequent references to religious imagery and language. Poems like ‘Stained Glass’, ‘Credo’ and ‘An Hour in Chapel Annexe’ are three that jump out after only a quick flick through the book. Although he wears his atheism with pride he has said that he doesn’t “deny the existence of a spiritual dimension within the human constitution”. That is evident from his poem ‘The Green Man’ which you can see him read here:

My favourite? Actually it’s still that very first poem but here’s my choice from Ancient Light. It is a perfect example of what I was talking about at the start of my interview with Dick. I can imagine sitting in Miss Williamson’s class, first period after lunch and still giddy after an hour’s freedom. She’d breenge into the room, gown flying behind her, all red hair and beady eyes with a sheaf of loose paper draped over her arm which we’d all see and pray was not a test. It wouldn’t be a test, no, perhaps worse, it would be a poem which would be passed out despite our protestations. What this time? ‘Toads’? ‘Hawk Roosting’? ‘My Last Duchess’?

FIRST ECLIPSE

A full eclipse, they told us:

bit by bit, a feeble daytime moon

will efface the sun, enfold us

in a counterfeit of night at noon.Around the edges of the lunar disc

a crown of fire will burn so bright

that scrutiny by naked eye would risk

blindness. Thrilled, we learned that lightthat violent must be sifted

through a darkened lens. And so

the grownups stood about, eyes lifted,

penitents in sunglasses who knowthe world’s about to end. Meanwhile,

we children lay in long grass, sharing

out the negatives I’d brought – a pile

of family snaps from home. Pairingthem up like playing cards, I dealt,

choosing for myself a glossy square

of clouds on a bright black day, and knelt

(like a penitent) to outstarethe slow mutating sun. Indistinct

at first, but then, from partial darkness,

bold and clear, Mum and Dad, arms linked,

strode out of their past. The starknessof that moment’s image – of their smug duality

before my birth – was blinding and I dropped

my hand. Lost in eclipse, I couldn’t see

where light began or where the darkness stopped.

It would be nice to imagine that one day in the future we see a similar scene enfold only it’s not Larkin, or Hughes or Browning. No, it’s some bloke called Dick Jones. And I can just hear the kids: “Never heard of him. And look at it! It rhymes in all the wrong places.”

It would be nice to imagine that one day in the future we see a similar scene enfold only it’s not Larkin, or Hughes or Browning. No, it’s some bloke called Dick Jones. And I can just hear the kids: “Never heard of him. And look at it! It rhymes in all the wrong places.”

But then there will be this one speccy kid in the third row from the window near the back whose just read the poem over to himself when it hits him: Oh… my… God.