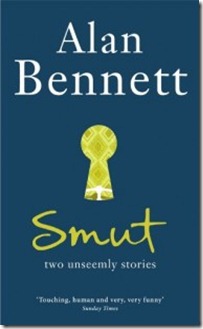

"... How much better ... how much healthier ... had all these persons, these family members, been more candid with one another right from the start. – Alan Bennett, Smut

Sex is a part of life, in fact without sex there’d be no life. I’m less curious about it than I used to be but I still find I can be distracted from what I’m doing when some salacious news item passes my way. Little actually shocks me. It just underlines how narrow my own life experiences have been and how poorly I understand people. I’m as puzzled by people who practice auto-erotic asphyxia as I am by people who listen to opera for pleasure. I don’t get any of them. I’ve tried listening to opera to see if I could develop a taste for it and’ve pretty much given that up as a bad job, but having been an asthmatic all my life I can conceive of no earthy pleasure at all in not being able to breathe so, no, I’ve not tried to strangle myself nor anyone else.

There is a single truth that holds true for all people: their parents had sex. If only the once. My wife just said, “What about in cases of artificial insemination?” to which I answered, “Well, at least the fella had sex.” “Children always assume the sexual lives of their parents come to a grinding halt at their conception,” so wrote Alan Bennett. We don’t like to think about our parents having sex which is odd because we, usually, are quite happy to have sex ourselves. Every generation thinks they invented sex or if not exactly invented it—given the fact their parents somehow managed it—they’ve been the ones to master it. I actually think the thing with our parents is more to do with old people having sex as opposed to just our parents but I might be wrong.

“People shouldn’t think I’m cosy”

Appearances can be deceiving. I suppose that’s where the notion of seemliness comes from. People aren’t interested in how things are, only how they seem. Alan Bennett never wrote Keeping up Appearances—despite the fact it features one of his favourite actresses—but he could have. Or, maybe not. It was actually written by fellow-Yorkshireman Roy Clarke. Bennett’s characters are generally more rooted in reality; Clarke’s tend to be more caricatured. There’s definitely common ground there, though. Many of Bennett's characters are unfortunate, downtrodden and not a little sad. Life has dragged them to an impasse or else passed them by. In many cases they’ve met with disappointment in the realm of sex and intimate relationships, largely through tentativeness and an inability to connect with others. Michael Frayn has noted that a lot of his work is about that moment when people wake up to the fact that they have passionate feelings and Bennett writes about these people with such compassion it’s hard not to feel something for even the traitors Anthony Blunt (A Question of Attribution) and Guy Burgess (An Englishman Abroad).

Appearances can be deceiving. I suppose that’s where the notion of seemliness comes from. People aren’t interested in how things are, only how they seem. Alan Bennett never wrote Keeping up Appearances—despite the fact it features one of his favourite actresses—but he could have. Or, maybe not. It was actually written by fellow-Yorkshireman Roy Clarke. Bennett’s characters are generally more rooted in reality; Clarke’s tend to be more caricatured. There’s definitely common ground there, though. Many of Bennett's characters are unfortunate, downtrodden and not a little sad. Life has dragged them to an impasse or else passed them by. In many cases they’ve met with disappointment in the realm of sex and intimate relationships, largely through tentativeness and an inability to connect with others. Michael Frayn has noted that a lot of his work is about that moment when people wake up to the fact that they have passionate feelings and Bennett writes about these people with such compassion it’s hard not to feel something for even the traitors Anthony Blunt (A Question of Attribution) and Guy Burgess (An Englishman Abroad).

Having remained unwed well into middle age it was generally assumed Bennett was gay although he never said yea or nay for many years. When pressed once at an Aids benefit back in the eighties to confirm whether he was gay or what, Bennett told the actor Ian McKellan: "That's a bit like asking a man crawling across the Sahara whether he would prefer Perrier or Malvern water." The fact is he is… ish—he’s lived with magazine editor Rupert Thomas for years—but it’s never as simple as that because he also had a long time relationship with Anne Davies, his former housekeeper; he’s on record as saying fell in love with her within a fortnight of the meeting and their relationship continued until her death in 2009. In an article in The Independent, Billy Kenber writes:

The playwright, who packs his works with autobiographical references, told Radio 4's Front Row programme last week: "If there was any sex going, you'd go for it, but it didn't really matter which side it was on. There'd been something of both in my life, but not enough of either."

Davies once said: "He was always gay, but he thought men didn't like him. It's like not being picked for the team at school. I was the only woman he'd ever been close to. I was like an earthquake, turning his life upside-down, with my kids and lovers and mess."

Needless to say the national press got its knickers in a right twist over that revelation but, as Bennett himself noted in his diary, “All you need to do if you want the nation's press camped on your doorstep is to say you once had a wank in 1947.” (Anyone who doubts the veracity of that claim that read this.) I mention this because for some reason people tend not to associate that nice man Alan Bennett with sex. He’s a national treasure after all—along with the likes of the Attenborough brothers, Stephen Fry and Judi Dench—and these people can do no wrong. I’m not suggesting that Bennett has done anything wrong—people with a stricter set of moral values than mine please feel free to disagree—his lifestyle choices are his own but I mention the above to remind everyone that long before he became a national treasure he was just a bloke from Leeds looking for love, like most of us, in all the wrong places.

Sex crops up in Alan Bennett’s writing with surprising (appalling?) regularity. Even his famous Talking Heads are far from free of it: Susan, in A Bed Among the Lentils, has an affair with an Asian grocer; Lesley, in Her Big Chance finds herself cast in a soft-core porn film; Miss Fozzard, in Miss Fozzard Finds Her Feet,  ventures into benign prostitution; Rosemary’s friend, on whom she develops a crush, in Nights in the Garden of Spain,kills her husband after years of ritual sexual abuse and, I expect the hardest one for most people to watch, Wilfred, in Playing Sandwiches, is a paedophile struggling—and, ultimately, failing—to keep on the straight and narrow. We prefer to remember Thora Hird’s two captivating performances in A Cream Cracker under the Settee and Waiting for the Telegram or Patricia Routledge in A Lady of Letters or even Bennett himself in A Chip in the Sugar.

ventures into benign prostitution; Rosemary’s friend, on whom she develops a crush, in Nights in the Garden of Spain,kills her husband after years of ritual sexual abuse and, I expect the hardest one for most people to watch, Wilfred, in Playing Sandwiches, is a paedophile struggling—and, ultimately, failing—to keep on the straight and narrow. We prefer to remember Thora Hird’s two captivating performances in A Cream Cracker under the Settee and Waiting for the Telegram or Patricia Routledge in A Lady of Letters or even Bennett himself in A Chip in the Sugar.

Certainly sex is a subject that he finds himself talking about more and more:

He says there is nothing he would hesitate to write about, if he chose. “Not now. I think once upon a time I would have. I just wouldn’t have wanted people to know too much about me. But I am so old it makes no difference now, does it? I have been around so long. And I also think people don’t care now in quite the same way.” Does this account for the increased amount of sex in his writing? “Maybe so. People think it is to do with me. I think it is to do with the times as much as anything else. Or maybe one is just running out of things to say.” – Sarah Crompton, ‘Alan Bennett, interview: “people shouldn't think I'm cosy”’, The Telegraph, 30 November 2012

In describing Bennett’s book Smutone of the reviewers on Amazon said this: “A ‘nice’ book about sex—only Alan Bennett could've done it!” It really hits the nail on the head, doesn’t it? He’s a bit like Morgan Freeman that way only in Bennett’s case he doesn’t even have to do the talking. As long as it’s his words then everything’s somehow more palatable, nicer. If you were going to your doctor to find out if you had cancer he’s the person you’d want sitting opposite you. I find it impossible to read anything by him or watch anything written by him without certain expectations and he always, always delivers because, with Bennett, it’s the journey that matters, not clever plotting or witty punch lines (although he’s perfectly capable of both).

Smut is comprised of a novella, The Greening of Mrs Donaldson and a novelette, The Shielding of Mrs Forbes although Bennett describes them as “long short stories”. They’re set in the present but there’s something slightly old-fashioned about both of them. Few are so awkward these days as to insist people use their honorific but there are places where it would feel more appropriate than others, a court of law for instance or a doctor’s office. I’m not exactly an old man but it does still rankle me when people I don’t know call me ‘James’ (especially telesales callers); they should say, “Do you mind if I call you ‘James’?” and let me grant them permission—“It’s ‘Jim’, actually”.

Smut is an old-fashioned word. It’s the kind of word my mother would’ve used: “We’ll ‘ave none o’ that smutty talk in ’ere.” (Remember my mother was a Lancashire lass.) It’s an objection I see raised now and then against Bennett and, to be fair, he is and always was (Larkin was the same, nostalgic before his time) but that’s his universe and I’m happy to buy into it—even if the word Bennettesque doesn’t exactly trip off the tongue—in just the same way as I accept the unrealities of P G Wodehouse’s or E F Benson’s worlds; it’s a part of their charm.

The Greening of Mrs Donaldson

Mrs Donaldson is fifty-five and recently widowed. She lives alone in a house that’s now too big—but more relevantly whose upkeep is now too much—for her and so, after staying “at home for weeks on end, a process Gwen, her married daughter, was pleased to dignify as ‘grieving’,” she’s found it necessary to supplement her income with a part-time job at the local medical school. To aid students in honing their diagnostic skills the management have hired a group of “Simulated Patients, as they were officially designated” to pretend they’re suffering from various ailments:

No special skills were said to be required, only the ability to memorise information and present it clearly. Nothing was said in the advert about acting ability or Mrs Donaldson would not have applied; self-confidence wasn’t mentioned either, which would have been another deterrent as Mrs Donaldson had always thought of herself as shy.

[…]

‘I don’t even see it as acting,’ she told her friend Delia in the canteen, ‘just a case of keeping a straight face. It’s a way of not being yourself.’

Delia was another member of the medical troupe.

‘It’s just nice to be looked at,’ said Delia, ‘even as a specimen. How often do young people ever look at you? At our age we’re invisible.’

As it happens Mrs Donaldson excels and becomes something of a favourite of Dr Ballantyne, the head of the unit; she has a talent for improvisation.

‘Ballantyne obviously fancies you,’ said Delia when they were talking in the canteen afterwards. And when Mrs Donaldson pulled a face, ‘You could do a lot worse.’

[…]

‘You’ve lost your husband, he’s lost his wife. A son in Botswana apparently and the daughter’s married an optician. He’s probably lonely.’

Okay, I know what you’re thinking. This is shaping up to be another As Time Goes By—I’m quite sure Geoffrey Palmer would made an excellent Dr Ballantyne to Judy Dench’s Mrs Donaldson—but that’s not the main thrust of this story. No. The job’s fine but the income is not and so Miss Donaldson decides to take in lodgers. Needless to say Gwen does not approve:

Okay, I know what you’re thinking. This is shaping up to be another As Time Goes By—I’m quite sure Geoffrey Palmer would made an excellent Dr Ballantyne to Judy Dench’s Mrs Donaldson—but that’s not the main thrust of this story. No. The job’s fine but the income is not and so Miss Donaldson decides to take in lodgers. Needless to say Gwen does not approve:

‘The first condom in the loo,’ she said to her husband, ‘and she’ll soon change her tune.’

As things go Mrs Donaldson is lucky:

[T]he two students sent to her by the university lodgings syndicate were in every respect but one not to be faulted. They were neat, quiet and they cleaned the bath and flashed the toilet and were so altogether discreet Mrs Donaldson scarcely knew they were in the house. Laura was a medical student and Andy, her boyfriend, was doing architecture.

Their one fault? They’re both regularly behind with the rent.

To be fair, the children, as Mrs Donaldson thought of them, were not unconcerned about their own fecklessness.

They assure her that they’ll be able to “work something out.” What precisely this might mean Mrs Donaldson gives no thought to. “They owed her money. It ought to be paid.” Once four weeks’ rent is overdue the lodgers broach the subject again.

‘We talked it over in bed last night,’ said Laura, ‘and it occurred to me that having seen you down at the hospital demonstrating we wondered if you would like it if. . .’

“We put on a demonstration for you,’ said Andy. ‘In lieu.’

Being about ages with Mrs Donaldson I have to confess that if there’s one expression I find myself struggling to grasp it’s, “It’s just sex.” It’s never been just sex with me. I’ve always regarded sex as something significant, something involving an emotional connection. That the goodnight kiss has turned into the goodnight bonk, well, that’s something I simply can’t get my head around.

"Have you ever seen anyone making love?" said Laura.

"To tell you the truth," said Mrs Donaldson pretending to cast her mind back, "I don’t think I have."

"Oh good," said Laura. "We were bothered it might not be much of a novelty."

"Oh no," said Mrs Donaldson, "it would. It would."

Though given the choice she still wasn’t sure she might have preferred marigolds.

Not wanting to appear ungrateful Mrs Donaldson acquiesces. Then follows probably the least-titillating—although far funnier—sex scene since “Adam knew Eve his wife” (Gen 4:1). Of course there are consequences but that’s as far as I’m going here.

The Shielding of Mrs Forbes

Having read a lot of online reviews of this book—especially the one-and two-star reviews—I can see one objection to this particular story was its lack of realism. Here’s what Bennett said in interview:

I wrote a play called Habeas Corpus and it’s a bit in that style. It’s a farce and not a realistic story

The protagonist in this story isn’t actually a Mrs Forbes; it’s the rather handsome (and rather gay) Graham Forbes who, as the story unfurls, we learn is contemplating marriage to a slightly older and less good looking woman going by the name of Betty—a name for some unknown reason his mother looks down on—who will, in due course, become the titular ‘Mrs Forbes’ and it takes no stretch of the imagination to conceive what she might need shielding from but one shouldn’t rush to any conclusions, not just yet. Why, in this so-called enlightened age, would Graham feel the need to do such a thing? I’ll come back to that.

The real stars of this piece, however, are his parents and were this ever turned into a play—which, indeed, it might have been as Bennett has admitted that often his short stories started off as ideas for plays that didn’t quite cut the mustard—I could see numerous venerable actors and actresses queuing up to play Mr and Mrs Forbes Sr. A typical exchange:

‘I suppose . . .’ mused Mr Forbes.

‘You suppose what?’

‘I suppose they’ve . . . had it off.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Done it. Got his leg over.’

There was a pained silence. It was an ancient battleground . . . what she called it, what he called it and whether he was allowed to call it anything at all.

‘I suppose you mean “made love”. Because I prefer not to think of it.’

‘She’s probably,’ said Mr Forbes, warming to the fray, ‘a bit of a goer.’

‘A goer? Edward. When are you going to learn that there are certain phrases you cannot use?’

‘I heard Graham use it.’

‘Graham is different. Graham is young, attractive and drives a sports car. He has a life with the top down and language to match. He can say “gay” and “bird” and “cool”, all the things young people say. You can’t. I heard you say “tits” the other night at the Maynards’. You’re too old to say “tits”’.

‘What age is that? When is the cut-off point? How old does one have to be still to say tit?’

‘It’s not a question of age. Some people can say it all their lives. Whereas you, you’ve never had enough dash.’

Don’t worry, Edward gets his own back when, during a dance with his wife at the wedding, he whispers obscenities into her ear and there’s nothing she can do about it, not that he doesn’t pay for it later.

So, yes, the wedding goes ahead. They both have their reasons. His is money. Betty is not short of a bob or two although the fact is Graham has no idea how wealthy and his wife has every intention of keeping it that way. She’s not daft—far, far from it:

She wasn’t wholly infatuated, though she liked the way he looked; but, so did he and that unfatuated her a bit. Still, she could be forgiven for thinking that her money entitled her to someone out of her own league.

Surprisingly the marriage is more of a success than either of them might’ve had a right to expect. Sex with his bride proves less of a chore than he imagined not that she succeeds in converting him and, as an occasional treat, he does go back to his old ways which is where he meets Gary or Trevor (actually Kevin) who might’ve been a lorry driver when he wasn’t being an interior decorator when he wasn’t being a rent boy when he wasn’t being a cop when he wasn’t being a blackmailer. No one is every quite what they seem but then neither was Betty who, although not entirely dissatisfied by Graham’s efforts in the bedroom, was not so satisfied that she had no time for a little bit on the side with, of all people, Graham’s dad which makes one wonder whether the ‘Mrs Forbes’ of the title might not actually be Graham’s mum rather than his wife. Of course there’s no reason it couldn’t be both.

The thing about protecting our loved ones is they usually need far less shielding than we imagine; women never have been the delicate flowers we like to paint them as and it turns to Betty to extricate her husband from the pickle he’s got himself into without playing all her cards if she can avoid it.

The bottom line

These two tales are big on dialogue, light on action and contain virtually no descriptions; people are described by their actions rather than their physical appearances. Neither is an especially serious or profound piece, although, now I think about it, that’s Bennett doing what Bennett does best, making the indigestible somehow not only palatable but actually pleasant. With the sole exception of the blackmailer there are no bad people here and as far as bad people go the blackmailer is in a league with those criminals from days of yore, dressed a bit like Frenchmen with bags with the word ‘swag’ written on them slung over their shoulders. There’s always the possibility that things are going to get serious but what’s the worst that could happen if Mrs Donaldson and Graham are outed? Actually both are but because this is the 21st century those who do learn of their shenanigans treat them the way they ought to be treated and see no reason to embarrass either of them; all they’ve done is cope the best way they could.

Both stories are told in the third person. For most writers that means an anonymous omniscient narrator but such is the weight of Bennett’s personality that never for a moment did I imagine that anyone else was telling these stories other than Bennett himself. Jackanory excepted, can you ever imagine sitting watching someone reading you a story on the telly? The radio, yes, but the telly? And yet there are hours and hours of Bennett doing just that. Or if not him then one of his proxies. So when he slips in expressions like ''the little woman'' or ''your good lady'' that’s Bennett talking and I don’t see that we should criticise him for that. Yes, his use of tense wanders—something I’m terribly guilty of so I’m not going to be picky—but, again, I prefer to treat the slips—if, indeed, they are slips (Charles Moore in The Telegraph thinks they are; Benedict Nightingale in The New York Times is more charitable)—as Bennett slipping through which is why there are three instances at least where he, to use a theatrical term, breaks the fourth wall and addresses us directly; the opening quote is one of those instances. Let me be explicit: we are not reading these stories; Alan Bennett is telling us these stories.

If the stories are a little cold—and they are—this is wholly due to Bennett’s characteristic delivery which can be a bit deadpan at times, a legacy of his Yorkshire upbringing. He is a reserved storyteller and so anyone looking for graphic depictions of acts of sexual congress will be sadly disappointed. Just as incontinence is called ''a little accident'' so direct, honest descriptions of who is doing what to whom are non-existent. Smut is a good title for this pairing—you can’t really call two stories a collection, can you?—because it’s a euphemistic expression and I can think of so many of these that my parents would’ve used like “women’s troubles” or “waterworks”. We don’t need everything spelled out. All I need to think of is my dad trying to tell someone the plot of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the voice in this book makes complete sense to me.

Is this Bennett at his best? Probably not but he’s another one like Woody Allen: even a ‘bad’ Woody Allen film is better than most people’s others and the same goes for Alan Bennett. Unlike some stories I’ve read of late the stories don’t hinge on the surprises and much pleasure can be gleaned from subsequent rereading. The satire’s not biting but it’s still there, nibbling away at our preconceptions and showing us just how farcical life can still be.

Is this Bennett at his best? Probably not but he’s another one like Woody Allen: even a ‘bad’ Woody Allen film is better than most people’s others and the same goes for Alan Bennett. Unlike some stories I’ve read of late the stories don’t hinge on the surprises and much pleasure can be gleaned from subsequent rereading. The satire’s not biting but it’s still there, nibbling away at our preconceptions and showing us just how farcical life can still be.

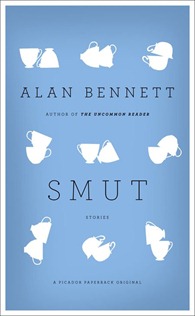

One last word: kudos to Picador for incorporating some of Christopher Silas Neal’s great "cupping" sketch ideas into their cover. Very clever and so appropriate. The Faber and Faber edition—the one I read—with its keyhole cover felt a bit flat after seeing it, although I did like it’s size, a bit smaller than your standard paperback.