I’ve had enough of grown-ups lying or not telling me the truth. I’m twelve years old. I can milk cows, for heaven’s sake. – Sue Reid Sexton, Rue End Street

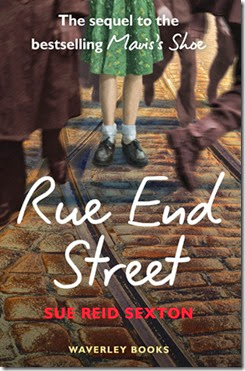

Sequels are a tricky business. It’s easy to see their appeal, both from an author’s perspective and a reader’s, but they’re fraught with dangers. With a standalone novel there’s little basis for expectations, whatever the blurb says and we all know how misleading blurbs can be. You might wonder if the book might go this way and that—especially if, as the case here, it’s a work of historical fiction—but that’s about it. Sue’s first novel was Mavis’s Shoe—you can read my review here—which dealt with the Clydebank Blitz as seen through the eyes of nine-year-old girl called Lenny Gillespie. Of course there’re people still alive who lived through these events—in some respects they’re the book’s target audience (well, primary audience)—and so the first job Sue was faced with was getting her facts straight because there’s nothing a reader of historical novels loves more than being able to say, “Oh, no, the door was actually olive green, not pine green.” I’m sure they do it unconsciously but they do do it.

I went to the Clydebank book release event on Wednesday 25th of June and it was interesting hearing Sue talk about how much research went into this book—she talked to survivors and visited places—and it’s impossible not to admire the dedication that these authors put into trying at least to get their facts straight. Not that she’s obsessive about it. In one of the endnotes to Rue End Street Sue mentions the paper mill at Overton:

The paper mill … actually closed in 1929 and the buildings were partially destroyed in 1939. I was working from an older map and did not discover this fact until that part of the book was written. It was so spectacular a spot for such an important moment, as visitors to Loch Thom will know, that it just had to stay in.

And I agree with her although to my mind the particular encounter that takes place there was so intimate that it could’ve happened anywhere; everything disappears around them; it’s just the two people involved. But this is me jumping way ahead of myself.

![Mavis Shoe[4] Mavis Shoe[4]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-z8TWnrZN3gU/U7PwF0R8XTI/AAAAAAAAIks/pWiJ47izvLE/Mavis%252520Shoe%25255B4%25255D_thumb%25255B1%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800) Sue says she’d no plans to write a sequel to Mavis’s Shoe but people wanted more and so she started to wonder what might satisfy them. Because she would now be writing for an audience with genuine expectations and in many cases a real fondness for the characters involved. I was quite touched at the reading when Sue apologised for having to kill off Mr Tait at the start of the book because it was clear that some in the audience had developed a soft spot for the character, but as she said, “He had to go.” Of course he didn’t have to go—the guy could’ve lapsed into a coma and woken up at the end of the book—but I’d probably have killed him off too. Cleaner.

Sue says she’d no plans to write a sequel to Mavis’s Shoe but people wanted more and so she started to wonder what might satisfy them. Because she would now be writing for an audience with genuine expectations and in many cases a real fondness for the characters involved. I was quite touched at the reading when Sue apologised for having to kill off Mr Tait at the start of the book because it was clear that some in the audience had developed a soft spot for the character, but as she said, “He had to go.” Of course he didn’t have to go—the guy could’ve lapsed into a coma and woken up at the end of the book—but I’d probably have killed him off too. Cleaner.

The big question—and one she clearly wrestled with for some time—was what to do with Lenny. Sue’s solution was an intriguing one, partly obvious, partly inspired. Whereas in the first book Lenny’s searching for her sister, in the sequel we have her searching for her dad. Because that’s what people really want from a sequel: the same but different. Only as the book progresses what she ends up searching for is not so much her dad but the truth about her dad. It turns out her dad was not the man she thought he was but then who’s dad is? There comes a point in every kid’s life—and about twelve is as good an age as any (that’s exactly when it happened to me)—when the scales fall off your eyes and you become aware that your dad’s merely a man with faults and flaws:

I pictured Mr Tait in his brown suit standing there with me admiring the view and what he’d say. ‘Your dad’s your dad,’ he’d say, ‘whatever kind of man he is.’

Mr Tait may be “D-E-A-D dead” but he’s not gone. Not by a long chalk. He’s a constant source of encouragement and strength to Lenny as she heads off in her search for the truth. Of course he’s only a voice in her head but his importance as a character can’t be overstated. Everyone uses him as a touchstone. Even in death he’s still a key figure.

So, how to start the ball rolling? In the opening chapter Mr Tait’s ill. In fact he’s dying. Lenny is in attendance and he calls her over:

‘Lenny,’ whispered Mr Tait.

‘Yes, Mr Tait.’

He raised a hand from his lap to indicate I should come closer.

Ordinarily I love the batter of the rain on the roof and the wind whipping the corners of our home, because it’s home and it’s cosy inside and we’re all in there together, but that day it was so stormy, and with the wind roaring through the trees around us, I couldn’t hear a word Mr Tait was saying. His voice was always soft and gentle but somehow you could always hear it no matter what. That afternoon he was so weak I couldn’t make anything out at all, so I put my finger in one ear and the other ear right up close to his mouth and waited. I felt his breath on my neck and the dryness of his lips brushed against my ears like autumn leaves. These were things I hadn’t felt before because Mr Tait was never one to show affection by touching. He’d only to call me ‘my dear’ and then I’d know he was the best friend I could ever have.

‘My dear,’ he whispered, and then he coughed again and I had to get out of the way. He sounded like little farthings rattling in a collection box [farthings were still legal tender until 1960], and when he’d finished he was like the wheeze of the fire. He waited a moment, then gave a little nod to indicate I should put my ear back up close. I was scared, I don’t mind saying so, but I always did what Mr Tait told me, usually. I heard him say ‘don’t touch’ and ‘cup’ and ‘keep girls away’ and ‘mum back’ and ‘Barney’. Then he sighed and I could hear his breathing like the fire again. After a minute he went on. ‘Your dad,’ he said, and ‘not far’ and ‘find’ and ‘under bed’. This surprised me because no-one hardly ever talked about my dad. My dad was a complete no-no as far as conversation was concerned. Although we didn’t know where he was and everyone thought he was ‘missing presumed dead.’ I was absolutely certain he wasn’t under the bed.

She does, however, look later, just to be sure, although not seriously and that’s the last Mr Tait ever says to her. We learn he’s been suffering from TB and pneumonia and dies shortly afterwards which leaves the family with a few problems, the whereabouts of Lenny’s dad being the least of them. Although Tait had acted as a father to the kids and provided financial support, the fact is, although many people didn’t believe this, he and Lenny’s mum were not living as husband and wife. He had offered to marry her (no doubt realising he wasn’t long for this world) so that when he died she’d receive a widow’s pension but as she was still married this wasn’t practical. Without Tait’s income the family’s faced with having to move back to Clydebank which no one wants—they’ve all become very attached to their hut in Carbeth—but needs must. Unless they can find another source of income. Lenny’s mum returns to work at Singers but that’s still not enough. Lenny, being Lenny, decides school can wait and tries to find work where she can and she’s surprisingly successful at landing odd jobs but the inevitable happens and one day she comes home to find everyone’s moved and she’s expected to pack up her own stuff and follow; a note with their new address has been left. Lenny, being Lenny (which is an expression that could preface practically any sentence about the girl) has her own plans and top of her list is: Find Dad.

As far as she’d aware her dad—also called Lenny Gillespie (at least that’s what she’d always believed)—was a soldier and off fighting the Nazis in some foreign country. But she learns quickly that’s not the case. He had been to war but on June 10th 1940 everything changed. That was the date the Italians entered the war and allied themselves with Germany. So what’s that got to do with Lenny’s dad? Well, quite a lot: it turns out her dad’s an Italian, at least his father was, and his real name is Leonardo Galluzzo. Overnight all Italians resident in the UK—including those fighting in the armed forces—are declared enemy aliens and potential fifth columnists. Thousands were arrested and shipped off to internment camps. In England most went to the Isle of Man but in Scotland—fortuitously for Sue’s book—three of the camps were reasonably close to Clydebank: Blairvadoch Camp, Rhu, Helensburgh, Stuckenduff Camp, Shanden, Helensburgh and there was a third at Whistlefield. (You can read an interesting article about them here.) This is where Lenny believes her dad is and so sets off to find him, not quite sure why she needs to find him but hoping against hope that in doing so she’s find the answer to her family’s problems. If she’d thought things through she’d have realised the folly of her course of action but she’s twelve (and she’s Lenny) and so off she goes half-cocked.

One of the reasons Sue was drawn to write her first book was that so little was known about the bombing of Clydebank. London and Coventry were still alive in the public consciousness but poor old Clydebank was in danger of being forgotten. Another historical fact—and one that people are more than happy to forget—is how the foreign nationals were treated during the war so this was a most worthwhile subject for a novel.

At its heart Rue End Street is plotted as a mystery novel with all the necessary coincidences, contrivances and conveniences in place to get the hero where she needs to be albeit usually by an unnecessarily convoluted route. This is the book’s  weakness although to be fair this is the weakness of all mystery novels. A typical example is the going by the matchbook trope. Lenny needs information and assistance and she invariably gets what she needs when she needs it. To Sue’s credit not everyone the girl encounters is helpful—this is wartime and sharing information, even with twelve-year-old girls, is frowned upon (Loose lips sink ships)—but, for my tastes, things still come a little too easily to her. Most readers won’t notice or care because it’s necessary for her to get where she’s going and as long as what or who assists her could have happened—it’s not as if Mr Tait appears to her in a dream and provides map coordinates or anything—then they’re willing to buy into it. Also it was a different time and even now Scots are—at least in the Greater Glasgow area—friendly, helpful and non-judgemental. So when Lenny’s trying to cross the Clyde without the requisite pass—not enough to have a ticket back then—for an adult who she’s never met before to step up and pretend to be a relative isn’t such a stretch.

weakness although to be fair this is the weakness of all mystery novels. A typical example is the going by the matchbook trope. Lenny needs information and assistance and she invariably gets what she needs when she needs it. To Sue’s credit not everyone the girl encounters is helpful—this is wartime and sharing information, even with twelve-year-old girls, is frowned upon (Loose lips sink ships)—but, for my tastes, things still come a little too easily to her. Most readers won’t notice or care because it’s necessary for her to get where she’s going and as long as what or who assists her could have happened—it’s not as if Mr Tait appears to her in a dream and provides map coordinates or anything—then they’re willing to buy into it. Also it was a different time and even now Scots are—at least in the Greater Glasgow area—friendly, helpful and non-judgemental. So when Lenny’s trying to cross the Clyde without the requisite pass—not enough to have a ticket back then—for an adult who she’s never met before to step up and pretend to be a relative isn’t such a stretch.

Like most mystery novels this is also a quest and if Sue had decided to pitch this book to kids or young adults then a title like The Quest for Lenny’s Dad would’ve been a perfect title. Having a twelve-year-old narrate does create its own problems because obviously Lenny has limited insight and life experience. She doesn’t, for example, realise that she’s starting to be attracted to boys “in that way” and although she has some ideas about sex she’s far more innocent than any twelve-year-old would be today. So there are times when this feels like a book aimed for older children and young adults—although Sue, during the Q+A that followed her reading said that wasn’t the case—and, as such, I found the book a lighter read than I prefer; I read the 421 pages over three days and didn’t feel I was stretching myself. It reminded me of books like Reinhardt Jung’sDreaming in Black and White and Jerry Spinelli’s Milkweed, books specifically aimed at a younger audience but that doesn’t mean that older readers—and I’m thinking especially of readers who remember World War II and probably aren’t big readers—won’t enjoy it. It was obvious from the audience reaction at the reading—which was clearly a larger turnout that they’d been expecting and extra seats were needed—that a number had fallen in love with Lenny on reading Mavis’s Shoe.

Which leads me to the question: Do I have to read Mavis’s Shoe first? I would say, yes. Sue does do her best to bring us up to speed but really she’s just reminding those who’ve read the first book of the important details and not providing a detailed backstory for newbies. You could read it on its own and it would work but—and, of course, there’s no way I can tell because I have read Mavis’s Shoe—I don’t think it stands as well on its own as the first book did. This isn’t a criticism, merely an observation. I’m sure many people who came to Mavis’s Shoe were interested in the Clydebank Blitz. Those who continue will do so less because of the book’s historical setting and more because Lenny’s impressed herself on them. She’s a compelling protagonist and it’s not hard to root for her.

Of course you know she’s going to find her dad. It would be a disappointing read if she didn’t. But it’s the truth—or, to be honest, the truths—about her dad that are uncovered along the way that raise the standard of this book. Finding her dad doesn’t solve the family’s bigger problems but Lenny does grow up (or at least takes a significant step towards growing up) because of her adventure.

I’m sure there will be those who want to know what happens to Lenny next and I’ve no doubt that if she were to find herself in another novel by Sue Reid Sexton it would be fun to see what happens to her. Personally I’d rather see this as the end to her story. The two books form a nice arc. Quit while you’re ahead. That would be my advice.

One interesting point: Rue End Street was simultaneously published in Braille. You can read more about that on the Royal Blind website.

***

Sue Reid Sexton is a writer of fiction, including novels, short stories and poetry. She was also a psychotherapist and counsellor for ten years, specialising in trauma, and before that she was a social worker in homelessness and mental health for another ten years. Now she dedicates herself to writing fiction and is an active member of Scottish PEN.

Sue Reid Sexton is a writer of fiction, including novels, short stories and poetry. She was also a psychotherapist and counsellor for ten years, specialising in trauma, and before that she was a social worker in homelessness and mental health for another ten years. Now she dedicates herself to writing fiction and is an active member of Scottish PEN.

She’s interested in the use of writing for health, as a way of understanding the self, for exploring experience, for sustaining identity and enabling the coming to terms with change. This is in addition to creative writing as art. She’s also interested in working with all groups but in particular those who might use groups or writing workshops for those reasons (and many more).

Further reading

The internment of an Italian from Glasgow

POW Camp Summary WWII (Scottish camps only)

Anti-Italian Riots (an extract from the book The Internment of Aliens in Twentieth Century Britain)