“I am a brain, Watson. The rest of me is a mere appendix.” – Arthur Conan Doyle, ‘The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone’

“I have no understanding of love,” he said miserably. “I have never made claim that I do.” So says the protagonist of Mitch Cullin’s new novel. And yet this is a book all about love. Well, loves. Different kinds. But let’s start with one of my loves: Sherlock Holmes. I’m a big fan. I’ve watched everything that’s ever been televised since I was a kid from Basil Rathbone on including the spoofs like Without a Clue although the man I think of as my first Holmes is actually Peter Cushing and although his characterisation may not be on a par with Jeremy Brett’s—surely the definitive performance—you never forget your first Holmes. I’ve enjoyed the recent spate of adaptations, modernisations and reimaginings, too—if you’ve never seen Jonny Lee Miller in Elementary I urge you to check out the show if only for Lucy Liu’s wonderfully-understated Joan Watson—but oddly enough I haven’t actually read any of the original novels or short stories. Kept meaning to but never quite got round to it. So when Canongate let me know that they were publishing a new Sherlock Holmes novel I thought it was time to rectify that omission. I read very little about the book beforehand. I knew it was set in 1947, Holmes is now ninety-three, retired, living on the southern slope of the Sussex Downs and, as you might expect of any ninety-three-year-old man, struggling with his memory.

![Actors who've played Holmes Actors who've played Holmes]()

I was expecting a detective novel. Probably not an unreasonable assumption. I wasn’t expecting great literature but I was okay with that. The book I read immediately prior to this was Margaret Drabble’sThe Millstone which I thoroughly enjoyed and is a beautifully-written, well-constructed work of literary fiction. Any author would have a hard time following that. So you can imagine my delight when I opened up A Slight Trick of the Mind and began to read a beautifully-written, well-constructed work of literary fiction. This doesn’t mean there’s no detection in the book—this is still a Sherlock Holmes novel and the man is incapable of switching off his powers of deduction—but this is not a case, not in that sense, although there is plenty of stuff to solve if only “the confounding enigmas that were his pockets”:

[O]ften small items went in without much thought—bits of paper, broken matches, a cigar, stems of grass, an interesting stone or shell found upon the beach, those unusual things gathered during his walks—only to vanish or appear later as if by magic.

There are three storylines all containing at least one bona fide mystery to be solved:

- The distant past: Sherlock in his prime—and for once sans Watson—solves the mystery of where his client's wife goes during the day. Whereas the rest of the book is written in the third person we learn of this case directly from Holmes in the form of a written record entitled The Glass Armonicist.

- The recent past: Sherlock and a Japanese companion with whom he has been corresponding wander around Japan in search of prickly ash, a plant that allegedly increases longevity.

- The present: Having just returned from Japan. Sherlock resumes his normal daily routine. This thread focuses on his relationships with his housekeeper, Mrs Munro, and her fourteen-year-old son, Roger.

Sherlock Holmes is a fictional character. I know that may sound like I’m stating the obvious here so let me clarify. The ‘Sherlock Holmes’ that John Watson presented to the world through his writings is not the man we get to meet in this novel. It turns out Watson had a talent for embellishment and, on occasion, downright fabrication. When asked if he owns any copies of John’s books, Holmes responds:

Actually, I possess none—not even the flimsy paperbacks. Truthfully, I've only read a handful of the stories—and that was many years ago. I couldn't instil in John the basic difference between an induction and a deduction, so I stopped trying, and I also stopped reading his fabricated versions of the truth, because the inaccuracies drove me mad. You know, I never did call him Watson—he was John, simply John. But he really was a skilled writer, mind you—very imaginative, better with fiction than fact, I daresay.

So the man we get to meet in this novel is the real Sherlock Holmes or at least a shadow of the real Sherlock Holmes, a man who walks with two canes to steady him, although:

[H]e really required only the support of the right cane while walking; the left cane, however, had an invaluable dual purpose—to give him support should he lose hold of the right cane and find himself stooping to retrieve it, or to stand in as a quick replacement should the right cane ever become irretrievable.

Even as an old man he’s still thinking two moves ahead.

I said this was a book about loves. Let me elucidate. In 'The Adventure of the Three Garridebs', Watson is shot in an encounter with a villain and although the bullet wound proves to be “quite superficial” in itself, Watson is struck by Holmes's reaction:

It was worth a wound; it was worth many wounds; to know the depth of loyalty and love which lay behind that cold mask. The clear, hard eyes were dimmed for a moment, and the firm lips were shaking. For the one and only time I caught a glimpse of a great heart as well as of a great brain. All my years of humble but single-minded service culminated in that moment of revelation.

That Holmes loves Watson has never been in doubt although when Holmes deduces his Japanese friend Tamiki Umezaki’s sexual orientation the man responds with this:

“I will say your observations about me and Hensuiro aren't terribly surprising. Without being too blunt—you are a bachelor who lived with another bachelor for many years.”“Purely platonic, I assure you.”“If you say so.”

In ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ Watson describes the high regard in which Holmes held Irene Adler, a retired American opera singer and actress:

![Glass Armonica Glass Armonica]() It seems, however, that there was another woman of whom John was to learn nothing. In The Glass Armonicist Holmes records how he solved what he calls The Case of Mrs. Ann Keller of Fortis Grove. No doubt Watson would’ve thought of a catchier title but this is Holmes’s record: accurate if uninspired. As cases go it barely tasks him so why, all these many years later, would he sit down to record it lest it be lost to him? Quite simply because of Mrs. Ann Keller of Fortis Grove and what he describes as a “common, unremarkable photograph of a married woman [with an] alluring, curious face”.

It seems, however, that there was another woman of whom John was to learn nothing. In The Glass Armonicist Holmes records how he solved what he calls The Case of Mrs. Ann Keller of Fortis Grove. No doubt Watson would’ve thought of a catchier title but this is Holmes’s record: accurate if uninspired. As cases go it barely tasks him so why, all these many years later, would he sit down to record it lest it be lost to him? Quite simply because of Mrs. Ann Keller of Fortis Grove and what he describes as a “common, unremarkable photograph of a married woman [with an] alluring, curious face”.

To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler...yet there was but one woman to him, and that woman was the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.

It seems, however, that there was another woman of whom John was to learn nothing. In The Glass Armonicist Holmes records how he solved what he calls The Case of Mrs. Ann Keller of Fortis Grove. No doubt Watson would’ve thought of a catchier title but this is Holmes’s record: accurate if uninspired. As cases go it barely tasks him so why, all these many years later, would he sit down to record it lest it be lost to him? Quite simply because of Mrs. Ann Keller of Fortis Grove and what he describes as a “common, unremarkable photograph of a married woman [with an] alluring, curious face”.

It seems, however, that there was another woman of whom John was to learn nothing. In The Glass Armonicist Holmes records how he solved what he calls The Case of Mrs. Ann Keller of Fortis Grove. No doubt Watson would’ve thought of a catchier title but this is Holmes’s record: accurate if uninspired. As cases go it barely tasks him so why, all these many years later, would he sit down to record it lest it be lost to him? Quite simply because of Mrs. Ann Keller of Fortis Grove and what he describes as a “common, unremarkable photograph of a married woman [with an] alluring, curious face”. Because of Holmes’s longevity it seems that all the usual characters we’ve come to know and love have now passed on: John Watson is dead; Mrs Hudson who accompanied him to the Sussex farmhouse upon his retirement is dead; his brother Mycroft is dead and one can only assume Inspector Lestrade is dead although no mention is made of him. His relationship with Mrs Munro, the latest in a number of housekeepers he’s employed over the years, is unremarkable but the same cannot be said of his feelings towards her son:

[W]hile he rarely enjoyed the company of children, it was difficult avoiding the paternal stirrings he harboured for Mrs. Munro's son (how, he had often pondered, could that meandering woman have borne such a promising offspring?). But even at his advanced age, he found it impossible to express his true affections, especially toward a fourteen-year-old whose father had been among the British army casualties in the Balkans and whose presence, he suspected, Roger sorely missed.

[…]“He's a good boy,” [his mother had] said when taking the job of housekeeper. “Keeps to himself, rather shy—very quiet, more like his father was. He won't be a burden on you, I promise.”

That news pleased Holmes at the time and for the longest time the two kept their distance but the boy’s fascination with Holmes’s beeyard provides unexpected common ground and by the time Holmes heads off to Japan he’s comfortable leaving his precious bees in what he regards as the safe hands of young Roger.

I don’t recall too many stories where Holmes ventures beyond the borders of the UK—obviously ‘The Final Problem’ where he tracks Moriarty to Switzerland is a notable exception—but we discover in this book that he’s actually travelled widely during his life although this is his first trip to Japan. Even in his dotage Holmes still receives a great deal of correspondence. One of Mrs Munro’s tasks is to sort his mail according to his precise instructions:

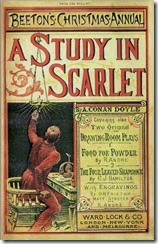

![ArthurConanDoyle_AStudyInScarlet_annual ArthurConanDoyle_AStudyInScarlet_annual]() Hence his trip to Japan. On arriving, though, he soon realises that his host has an ulterior motive for his invite. The man’s father had abandoned his family some forty years earlier and the last correspondence from him included a copy of A Study in Scarlet along with a letter to his wife which Umezaki translates for Holmes:

Hence his trip to Japan. On arriving, though, he soon realises that his host has an ulterior motive for his invite. The man’s father had abandoned his family some forty years earlier and the last correspondence from him included a copy of A Study in Scarlet along with a letter to his wife which Umezaki translates for Holmes:

From a wicker basket placed on the library table, she took out bundles of correspondence (letters bearing foreign postmarks, small packages, large envelopes), and, as instructed to do once a week, she began sorting them into appropriate stacks based on size. […] The letters to the left, the packages in the middle, the larger envelopes on the right.

[…]Rarely did he respond to any of it, and never did he indulge journalists, writers, or publicity seekers. Still, he usually perused every letter sent, examined the contents of every package delivered.

[…]Sometimes these lucky letters beckoned him elsewhere: an herb garden beside a ruined abbey near Worthing, where a strange hybrid of burdock and red dock thrived; a bee farm outside of Dublin, bestowed by chance with a slightly acidic, though not unpalatable, batch of honey as a result of moisture covering the combs one particularly warm season; most recently, Shimonoseki, a Japanese town that offered specialty cuisine made from prickly ash, which, along with a diet of miso paste and fermented soybeans, seemed to afford the locals sustained longevity (the need for documentation and firsthand knowledge of such rare, possibly life-extending nourishment being the chief pursuit of his solitary years).

Hence his trip to Japan. On arriving, though, he soon realises that his host has an ulterior motive for his invite. The man’s father had abandoned his family some forty years earlier and the last correspondence from him included a copy of A Study in Scarlet along with a letter to his wife which Umezaki translates for Holmes:

Hence his trip to Japan. On arriving, though, he soon realises that his host has an ulterior motive for his invite. The man’s father had abandoned his family some forty years earlier and the last correspondence from him included a copy of A Study in Scarlet along with a letter to his wife which Umezaki translates for Holmes: After consulting with the great detective Sherlock Holmes here in London, I realize that it is in the best interest of all of us if I remain in England indefinitely. You will see from this book that he is, indeed, a very wise and intelligent man, and his say in this important matter should not be taken lightly. I have already made arrangements for the property and my finances to be placed in your care, until such a time as Tamiki can take over these responsibilities in adulthood.

Holmes says he can’t remember meeting the man. Has he simply forgotten or is there more going on here?

These are three disparate threads and it’s hard to imagine that Cullin could weave them together and yet he manages it. The bees help.

Notably Doyle tried to kill of his creation when Holmes was at the peak of his popularity. Not that the public was having any of it. And there have been numerous writers who’ve chosen to quit while they’re ahead much to the irritation of their fans but we all know what happens when a great idea gets beaten to death. The thing is we know going into this that Holmes isn’t the man he was even if who we thought he was wasn’t who he really was. There’s a decent chance we’re going to be disappointed. And some readers have been. At time of writing 5% of the reviews on Goodreads gave the book a niggardly one star; that’s nineteen people; the average was 3.45. Valerie, who gave the book two stars, wrote:

There wasn't much that happened. There wasn't much character growth. There wasn't any action. There [were] just people talking to other people, people having thoughts, people walking around... that really sums it up, I'm sad to say. At first, it grabbed my interest because I was super curious to see where it was going with the three different timelines it was following. But then I started to suspect that it wasn't really going anywhere fascinating after all. & I was right.

She’s not wrong and if you are looking for the-Sherlock-you-know-and-love there is a good chance you will be dissatisfied. Max222 over on Amazon—he gives the book three stars—makes a valid point when he notes:

[I]s it really a Sherlock Holmes story? Not really I would argue. You see I was expecting it to be sad and moving which it is, but also to have a mystery in it—and it doesn't really. […] I realise the author is deliberately trying to show a different side to Holmes but really this could be any main protagonist. And I don't say that just because Holmes has been aged for the bulk of the novel, which is an idea I like—I just don't feel the Conan Doyle character was within these pages even aged 90.

Agreed but I’ve already addressed this. We’re told that the Holmes in the books was never the real Holmes:

I am afraid I never wore a deerstalker, or smoked the big pipe—mere embellishments by an illustrator, intended to give me distinction, I suppose, and sell magazines. I didn't get much say in the matter.

So, let’s just say for a moment, that this isn’t a Sherlock Holmes novel. Let’s just say this is a novel about some nonagenarian who happened once to work as a private eye or even as a detective in the Metropolitan Police. Would the story work? Indubitably. Holmes’s name will help sell the book but the book’s strength is that it doesn’t depend on the old guy being Holmes to work. But because he is Holmes a great deal of the groundwork is done for Cullin because all of us have some idea who Holmes is even if it is a flawed one. Whether the book is insightful is another matter. It depends on whether you expect your author to raise interesting questions and then to answer them or simply to raise interesting questions and leave you to ponder them. Mostly Cullin does the latter and I was fine with that. In a short interview over at GQ Cullin says:

[M]y version of Holmes is a highly metaphorical creation that, at the time, was used by me as a way to better understand my own father's struggle with dementia […] That said, my research and my writing of the book made every effort possible to be true in nature to Conan Doyle's character and the entire canon that contains him.

Life is a mystery and one would’ve hoped if anyone was going to ‘solve’ it, it would be Sherlock Holmes. He gives it his best shot but he really has left it too late. So, yes, this is a sad book but sadness, like love, is an emotion that comes in many shades and I’m still trying to decide what kind of sad I feel now I’ve finished it. Certainly not the disappointed kind.

The book is being filmed with Sir Ian McKellen playing the lead—an inspired (although at the same time obvious) choice I’d say—and one I’m looking forward to.

I loved this book. I’m well aware that there were a couple of times when Holmes’s dialogue wasn’t absolutely spot on but I’m not going to lop off a star for something as trivial as that. Now what we don’t want to see is a sequel. Either on the page or on the silver screen.

***

Mitch Cullin is the author of seven novels, and one short story collection, including the novel Tideland, the film adaptation of which was directed by Terry Gilliam, and the novel-in-verse, Branches. He lives between Arcadia, California and Tokyo, Japan with his long-term partner and frequent collaborator Peter I. Chang. As a teenager he was featured in USA Today in 1984 as one of the foremost Holmes fans in the world. According to his bio on Red Room: “He continues to write novels in decreasing spurts and increasing sputters, but usually he can be found ambling around his garden in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles County.”

Mitch Cullin is the author of seven novels, and one short story collection, including the novel Tideland, the film adaptation of which was directed by Terry Gilliam, and the novel-in-verse, Branches. He lives between Arcadia, California and Tokyo, Japan with his long-term partner and frequent collaborator Peter I. Chang. As a teenager he was featured in USA Today in 1984 as one of the foremost Holmes fans in the world. According to his bio on Red Room: “He continues to write novels in decreasing spurts and increasing sputters, but usually he can be found ambling around his garden in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles County.”