But whoso shall offend one of these little ones who believe in me, it were better that a millstone were hanged about his neck and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea (Matthew 18:6)

Margaret Drabble has been described as “a women’s novelist” although who first tarred her with that epithet I haven’t been able to ascertain, but according to The Cambridge Introduction to Modern British Fiction, 1950-2000 Ellen Cronan Rose has suggested that it’s nevertheless a useful label if it’s meant to indicate that “her subject was what it was like to be a woman in a world which calls woman the second sex.”[1] The term “women’s novelist” does feel like a restrictive—if not downright disparaging—term, suggesting that she’s writing both from a limited perspective and for a limited demographic. Drabble herself says that although many of her novels focus on “a specific section of women that I happen to know about, middle-class women with ambition, in other words,” she does not consciously write about women “in general terms.”[2] She says, “When I'm writing I don't think of myself wholly as a woman ... I've tried to avoid writing as a woman because it does create its own narrowness.”[3] This echoes what her peers, Iris Murdoch and A.S. Byatt, have said and much space has been devoted to arguing whether or not any of these three are feminist writers. I suppose there’s feminism and feminism-with-a-capital-f but either way I don’t imagine there’ll be many men out there who’ll want to read about the trials of an unmarried mother in the mid-sixties. And that would be their loss.

The second sex is an anatomy of what Drabble has called "the situation of being a woman" in a man's world. It asserts that one is not born but becomes a woman. De Beauvoir described "how woman undergoes her apprenticeship, how she experiences her situation, in what kind of universe she is confined, what modes of escape are vouchsafed her."[4]

I grew up a man in a man’s world. It still is a man’s world and I’m still a man. Things are changing, yes, but nowhere near as fast as they ought; conditioning—and there’s no better word for it—is hard to shake off. People read for lots of different reasons but one of the main reasons to do so as far as I’m concerned is so I can, for a few hours at least, get some idea what it’s like inside someone else’s head. And there’s nothing more intriguing as far as I’m concerned that a woman’s head. I grew up in a world where I was told—and accepted based on what little evidence I had—that women were not like “us”; we’d never understand them so why bother trying? Well, I don’t know about you but I don’t like not being able to get things.

A while back I read Margaret Drabble’s most recent novel, The Pure Gold Baby. It was the first of her books I’d read and I really didn’t know what she’d be like. This is how I opened my subsequent review:

![Pure Gold Baby Pure Gold Baby]() The thing is this was a book about motherhood and yet I still enjoyed it. So when Canongate told me they were bringing out a selection of Drabble’s back catalogue as ebooks, I jumped at the chance to read another and opted for (arguably) her most famous book, The Millstone, which just happens to be another one about motherhood. I was curious to compare the Drabble of 2014 with the Drabble of 1965. The Millstone is about an unmarried, young academic who becomes pregnant after a one-night stand and, against all odds, decides to give birth to her child and raise it herself. Not all that different from The Pure Gold Baby. At least on the surface.

The thing is this was a book about motherhood and yet I still enjoyed it. So when Canongate told me they were bringing out a selection of Drabble’s back catalogue as ebooks, I jumped at the chance to read another and opted for (arguably) her most famous book, The Millstone, which just happens to be another one about motherhood. I was curious to compare the Drabble of 2014 with the Drabble of 1965. The Millstone is about an unmarried, young academic who becomes pregnant after a one-night stand and, against all odds, decides to give birth to her child and raise it herself. Not all that different from The Pure Gold Baby. At least on the surface.

I didn’t expect to like this book. Don’t get me wrong, I didn’t set out with any agenda and had very few preconceptions but I still didn’t expect to like the book. I didn’t love it but I did like it and by liking it I don’t mean that I didn’t hate it; I actually enjoyed reading it; I looked forward to the next day when I could pick it up again; I wanted to know what was going to happen next; I invested something of myself in the book.

The thing is this was a book about motherhood and yet I still enjoyed it. So when Canongate told me they were bringing out a selection of Drabble’s back catalogue as ebooks, I jumped at the chance to read another and opted for (arguably) her most famous book, The Millstone, which just happens to be another one about motherhood. I was curious to compare the Drabble of 2014 with the Drabble of 1965. The Millstone is about an unmarried, young academic who becomes pregnant after a one-night stand and, against all odds, decides to give birth to her child and raise it herself. Not all that different from The Pure Gold Baby. At least on the surface.

The thing is this was a book about motherhood and yet I still enjoyed it. So when Canongate told me they were bringing out a selection of Drabble’s back catalogue as ebooks, I jumped at the chance to read another and opted for (arguably) her most famous book, The Millstone, which just happens to be another one about motherhood. I was curious to compare the Drabble of 2014 with the Drabble of 1965. The Millstone is about an unmarried, young academic who becomes pregnant after a one-night stand and, against all odds, decides to give birth to her child and raise it herself. Not all that different from The Pure Gold Baby. At least on the surface. The book opens:

My career has always been marked by a strange mixture of confidence and cowardice: almost, one might say, made by it. Take, for instance, the first time I tried spending a night with a man in a hotel. I was nineteen at the time, an age appropriate for such adventures, and needless to say I was not married. I am still not married, a fact of some significance, but more of that later. The name of the boy, if I remember rightly, was Hamish. I do remember rightly. I really must try not to be deprecating. Confidence, not cowardice, is the part of myself which I admire, after all.

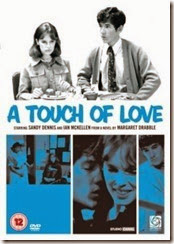

Now I don’t know about you but the voice I heard in my head from the very start was that of a young Judy Dench and I make no apologies for pointing your mind in that direction because I cannot imagine anyone delivering these lines better; I did try replacing her with Joanna Lumley for a paragraph or two but it didn’t work. In the 1969 film version (A Touch of Love, Thank You All Very Much, US)—which Drabble herself adapted—the part went to the not-dissimilar-looking Sandy Dennis who, despite being an American, was a decent choice and about the right age; Dench would’ve been a tad old although neither actresses possessed the especially “fine ![A_Touch_of_Love_FilmPoster A_Touch_of_Love_FilmPoster]() pair of legs” that Rosamund says she has and since Rosamund always speaks her mind and is ferociously-honest (at least on the printed page), if she says she has a “fine pair of legs” then they must be indeed fine. (Credit should go too to whoever cast Eleanor Bron as the best friend and Ian McKellan as the gay radio announcer).

pair of legs” that Rosamund says she has and since Rosamund always speaks her mind and is ferociously-honest (at least on the printed page), if she says she has a “fine pair of legs” then they must be indeed fine. (Credit should go too to whoever cast Eleanor Bron as the best friend and Ian McKellan as the gay radio announcer).

pair of legs” that Rosamund says she has and since Rosamund always speaks her mind and is ferociously-honest (at least on the printed page), if she says she has a “fine pair of legs” then they must be indeed fine. (Credit should go too to whoever cast Eleanor Bron as the best friend and Ian McKellan as the gay radio announcer).

pair of legs” that Rosamund says she has and since Rosamund always speaks her mind and is ferociously-honest (at least on the printed page), if she says she has a “fine pair of legs” then they must be indeed fine. (Credit should go too to whoever cast Eleanor Bron as the best friend and Ian McKellan as the gay radio announcer). Hamish is not who gets her pregnant. In fact some ten years flit by before that happens and as it happens it’s her first (and I suspect her last) attempt at any form of carnality—she closes her eyes throughout the whole procedure but does not think of England—although who knows what might unfold after the book’s final chapter? We don’t learn much about Rosamund’s upbringing: despite the fact her parents weren’t short of a bob or two, they were apparently committed Socialists although I don’t believe Socialists have anything particularly against sex. Drabble was brought up as a Quaker and Quakers also don’t have anything against sex in the right context. But Rosamund isn’t interested which is odd. What’s odder is that she’s not especially interested in love. (I thought all woman had romance on the brain.) She has her studies and for the most part they satisfy her. She is prone to occasional spells of loneliness and so, practical person that she is, has a number of friends, but friends she likes to keep at a distance:

It took me some time to work out what, from others, I needed most, and finally I decided, after some sad experiments, that the one thing I could not dispense with was company. After much trial and error, I managed to construct an excellent system, which combined, I considered, fairness to others, with the maximum possible benefit to myself.

This makes her seem a bit cold and calculated and I suppose she is on one level. Like most people at that time—remember the Summer of Love is still a couple of years off—she’s pretty ignorant about sex. Her male friends, however, don’t appear to be, but as they’re finding comfort elsewhere no one’s pressuring her to put out.

What do you think of when you hear the term ‘academic’? Someone who wiles her days away in the British Museum researching Elizabethan sonnet sequences? Someone who doesn’t own a TV? Someone who’s not really a part of life? I’m sure Drabble made Rosamund an academic for a good reason. She’s certainly no militant feminist. Not that she’s considered the matter and taken a stand. Rather the opposite. She’s never really been faced with issues of feminism or even femininity. She’s an intellectual, grounded, level-headed and in this context gender is academic. When she does finally get round to sex—an act where she needs to play the woman—what’s noteworthy about her chosen partner is that he is—as far as she’s aware—gay:

At the touch of my mouth, he took me in his arms and kissed me all over the face, and eventually we subsided gently together and lay there quietly. Knowing that he was queer, I was not frightened of him at all, because I thought that he would expect no more from me, and I was so moved and touched and pleased by the thought that he might like me, by the thought that he found me of interest. I was so happy for that hour that we lay there because truly I seemed to see him through the eyes of love, so irrationally valuable did he seem. I look back now with some anguish to each touch and glance, to every changing conjunction of limbs and heads and hands. I have lived it over every day for so long now that I am in danger of forgetting the true shape of how it was, because each time I go over it I wish that I had given a little more here or there, or at the very least said what was in my heart, so that he could have known how much it meant to me. But I was incapable, even when happy, of exposing myself thus far.

Why exactly he chooses to have sex with her we’ll never know. Charity? An act of kindness? Vague curiosity? Does he simply misread the signals? Rosamund wonders:

After all, I said to myself, people don’t do that to other people just because they think they ought to. Just through sheer politeness because they think they’ve been invited in to do it. People don’t work like that, I said to myself. He must have wanted it a bit, I told myself, or he wouldn’t have bothered. However kind he appears to be, he can’t be as kind as all that. He must be one of these bisexual people, I thought, or perhaps even he’s no more queer than I am promiscuous, or whatever the word is for what I pretend to be. Perhaps we appeal to each other because we’re rivals in hypocrisy.

What it isn’t, and this applies to the both of them, is love. Love is something Rosamund has a problem with. Ironic, then, that she would take as a subject Elizabethan love poets. She talks about having been in love with Hamish when she was nineteen but it’s clear that she’s just using ‘in love’ as a common expression and as indication of how the nineteen-year-old her felt she felt as opposed to how she truly felt:

When Hamish and I loved each other for a whole year without making love, I did not realize that I had set the mould of my whole life. One could find endless reasons for our abstinence – fear, virtue, ignorance, perversion – but the fact remains that the Hamish pattern was to be endlessly repeated, and with increasing velocity and lack of depth, so that eventually the idea of love ended in me almost the day that it began. Nothing succeeds, they say, like success, and certainly nothing fails like failure. I was successful in my work, so I suppose other successes were too much to hope for.

Motherhood will change all that. But first she has to get through the pregnancy and that actually takes up the bulk of a not-very-bulky book. Characteristically Rosamund views things dispassionately seeing no good reason why gravidity should get in the way of her career so doesn’t let it and makes plans to ensure that her child when born will also not get in her way. What I found interesting is the way she refers to the foetus as ‘it’ despite the fact the book’s clearly written by an older her sometime after the baby is born. Only after the birth do we discover the sex. Only then does Rosamund come face to face with love:

[The nurse] put her in my arms and I sat there looking at her, and her great wide blue eyes looked at me with seeming recognition, and what I felt it is pointless to try to describe. Love, I suppose one might call it, and the first of my life.[…]I used to think that love bore some relation to merit and to beauty, but now I saw that this was not so.

Having a child changes you. I’m not talking about physically because after the birth “the muscles of [her] belly snap back into place without a mark.” It changes you as a person. Unless you’re broken. Rosamund makes room for her daughter and adds the role of mother to the things she’s doing already but other than that she really does change very little; because she refuses to.

I simply did not believe that the handicap of one small illegitimate baby would make a scrap of difference to my career…

She loves the baby but only as a “small living extension” of herself, something she’s produced, like her thesis. That’s the thing about Rosamund. She’s not an everywoman; she’s a person and a flawed one. Not every woman would handle things as well as she does—not that she handles everything well, of course not (her early attempt at abortion is laughable)—and there are examples in the book of women who aren’t having such an easy time. She regains her figure but not all do:

[S]ome of the women looked as big as they had looked before. I am haunted even now by a memory of the way they walked, large and tied into shapeless dressing gowns, padding softly and stiffly, careful not to disturb the pain that still lay between the legs.

Drabble is known for her social commentary and what’s interesting is how badly the NHS come off in this novel, the crowded waiting rooms, the often insensitive nursing staff and the excessive paperwork.

There’re times you’d mistake Rosamund for a snob and you wouldn’t be wrong. She’s lived a privileged life. She’s not royalty or anything but she’s had a cushy time of it and this is the first time she’s had to be in the company of commoners and she cannot help but be moved by it. One of the most striking moments happens when, in the antenatal clinic, a mother she’s never met before asks her to hold her sleeping baby while she visits with the midwife:

There’re times you’d mistake Rosamund for a snob and you wouldn’t be wrong. She’s lived a privileged life. She’s not royalty or anything but she’s had a cushy time of it and this is the first time she’s had to be in the company of commoners and she cannot help but be moved by it. One of the most striking moments happens when, in the antenatal clinic, a mother she’s never met before asks her to hold her sleeping baby while she visits with the midwife:

She made her way off to the midwife’s room and I sat there with this huge and monstrously heavy child sitting warm and limp upon my knee, his nose slightly running and his mouth open to breathe. I was amazed by his weight; my legs felt quite crushed under it. I also realized that he was not only warm but damp; his knitted leggings were leaking quite copiously onto my knee. I shifted him around but did not dare to move much for fear of waking him and having to put up with his playing up something shocking: I was worried about whether the damp patch would show on my coat, and hoped it would not. I sat there for a good ten minutes with this child upon my lap; it was the first time I had ever held a baby and after a while, simultaneously with preoccupations about damp on my coat, a sense of the infant crept through me, its small warmness, its wide soft cheeks, and above all its quiet, snuffly breathing. I held it tighter and closed my arms around it.

She’s still pregnant herself at this point and so this is the first time she’s ever held a baby in her arms.

Rosamund is less of a feminist icon and more an independent woman. When she runs into the child’s father at the end of the book he says to her:

‘You seem to have done all right, you seem to have done as well as anyone.’

‘How do you mean?’ I said.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘by your own accounts, you’ve got a nice job, and a nice baby. What more could anyone want?’

‘Some people might want a nice husband too,’ I said.

‘But not you, surely?’ said George. ‘You never seemed to want a husband.’

‘No,’ I said, ‘perhaps I never did. Though I sometimes think it might be easier, to have one. It would be nice to have someone to fill in my income tax forms, for instance,’ and I pointed despairingly at the mess of papers laid out on the hearth rug.

‘You can’t have everything,’ said George.

‘No, indeed,’ I said. ‘And I have more than most people, I admit.’

For me this is what raised the book and kept my interest. Rosamund is a fascinating—although not always a sympathetic—character. That she happens to fall pregnant is neither here nor there. If she’d been faced with the task of nursing a terminally ill relative she would’ve handled things because that’s what she does. Ignorance is an inconvenience, nothing more. If you don’t know you find out. Obstacles can be worked around, even baby-shaped ones.

Rosamund is blinkered. If something (like a child) can be brought within her field of vision then good and well. But she’s not big on concessions. I found this anecdote about Drabble illuminating:

Margaret Drabble recalled how she managed to write a book about Wordsworth: "I wrote the whole thing—the re-write, that is—in the ten days when I was in hospital when my youngest child was born. I took my typewriter into hospital—I sat in the ambulance clutching it saying, 'Don't take that away.' My baby was born ten minutes after I got to hospital. And the minute I got into bed I got my typewriter and was able to get on. I had some lovely fish and chips and a nice evening's work."[5]

I can see some women being disturbed by her insouciance but there are those writers who work around real life and those who squeeze real life in where they can. Rosamund may not be a writer—Drabble was never an academic—but she is the kind of person who just gets on with stuff. I found her no less absorbing than Camus’sMeursault. When at one point the baby falls ill Rosamund, with the same dispassion and detachment with which Meursault talks about his mother, records:

For five minutes or so, I almost hoped that she might die, and thus relieve me of the corruption and the fatality of love. Ben Jonson said of his dead child, my sin was too much hope of thee, loved boy. We too easily take what the poets write as figures of speech, as pretty images, as strings of bons mots. Sometimes perhaps they speak the truth.

I said at the start of this article that this is a book about motherhood. Really it’s not and it’s not even a book about pregnancy. Pregnancy sought to entrap her—“I was in a human limit for the first time in my life, and I was going to have to learn to live inside it”—but she refuses to allow it to—having a remarkably easy time of it certainly doesn’t hurt (even labour only lasts a short time); motherhood she also hopes to bend to her will refusing even to involve her family. These are side issues though. This is a book about what it’s like to be driven. It’s an easy read—a deceptively easy read—but there’s some deep (and dark) stuff here and I’ve only touched on a fraction of it. Delusions need something to fuel them and money certainly helps. Had Rosamund grown up in Possilpark this would’ve been a completely different read.

One thing I should perhaps clarify is the fact that Rosamund, despite her failings as a person, is a good and not merely a good, but devoted mother. One of the most powerful scenes in the book—and even more so in the film—is where her child has needed to be hospitalised and the staff won’t allow her to see her. After trying to be patient and polite she’s finally had enough:

Claire Tomalin wrote that Drabble “is one of the few modern novelists who has actually changed government policy, by what she wrote in The Millstone about visiting children in hospital”. Now, thanks in part to Drabble, mothers will never have to scream like Rosamund in order to see their babies.

In his essay on The Millstone Peter Firchow comments on an affinity between Jane Austen and Drabble

[I]t is no doubt appropriate that Drabble should have suffered, as Austen did, from a habit of mind that confounds smallness of scope with smallness of mind. [...] The work of the miniaturist, it seems, is at present in ever greater disrepute than it was a century and a half ago.[6]

Not having read any Austen—although familiar enough with her work through various screen adaptations—I can also see that Drabble has much also in common with Anita Brookner who is likewise able to portray complex psychological motivations in simple, eloquent language and who similarly has an affinity for socially repressed women; additionally neither author overstays her welcome on the page. I suspect I’ll be reading more of both.

***

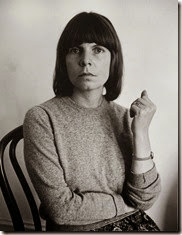

![NPG P1326; Dame Margaret Drabble (Lady Holroyd) NPG P1326; Dame Margaret Drabble (Lady Holroyd)]() Margaret Drabble was born June 5, 1939 in Sheffield, Yorkshire, England. Her father, John Frederick Drabble, was a barrister, a county court judge and a novelist. The author A.S. Byatt is her older sister.

Margaret Drabble was born June 5, 1939 in Sheffield, Yorkshire, England. Her father, John Frederick Drabble, was a barrister, a county court judge and a novelist. The author A.S. Byatt is her older sister.

Margaret Drabble was born June 5, 1939 in Sheffield, Yorkshire, England. Her father, John Frederick Drabble, was a barrister, a county court judge and a novelist. The author A.S. Byatt is her older sister.

Margaret Drabble was born June 5, 1939 in Sheffield, Yorkshire, England. Her father, John Frederick Drabble, was a barrister, a county court judge and a novelist. The author A.S. Byatt is her older sister. She attended the Mount School, York, a Quaker boarding-school, and was awarded a major scholarship to Newnham College, Cambridge, where she read English and received double honours. After graduation she joined the Royal Shakespeare Company at Stratford during which time she understudied for Vanessa Redgrave.

In 1960 she married her first husband, actor Clive Swift, best known for his role as the henpecked husband in the BBC television comedy Keeping Up Appearances, with whom she had three children in the 1960's; they divorced in 1975. She subsequently married the biographer Michael Holroyd in the early 1980's. They live in London and also have a house in Somerset.

Her novel The Millstone won the John Llewelyn Rhys Prize and she was the recipient of a Society of Author's Travelling Fellowship in the mid-1960's. She also received the James Tait Black and the E.M. Forster awards. She was awarded the CBE in 1980 and she was promoted to Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in the 2008 Birthday Honours.

***

One last clip, an indulgence. In this scene Rosamund is in labour and has been assigned to the wrong room. The actress who plays the nurse who notices isn’t credited (not even in IMDB) but no one could’ve played her better.

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

[1] Dominic Head ed., The Cambridge Introduction to Modern British Fiction, 1950-2000, p.86 . Here the quote is attributed to Ellen Cronan Rose but as she was an editor I suspect she is being misquoted. The same phrase is used by Suhasini Tapaswi in her book Feminine Sensibility in the Novels of Margaret Drabble on page 36; I’m assuming she’s referencing Rose’s book even if she’s not crediting her since The Novels of Margaret Drabble came out in 1980.

[2] Joanne V. Creighton, ‘AnInterview with Margaret Drabble’ in Dorey Schmidt ed. Margaret Drabble: Golden Realms, p.25 quoted in Lisa M Fiander Fairy Tales and the Fiction of Iris Murdoch, Margaret Drabble and AS Byatt, p.11

[3] Diane Cooper-Clark, ‘Margaret Drabble: Cautious Feminist’ in Atlantic Monthly 246, November 1980 p.19 quoted in Lisa M Fiander Fairy Tales and the Fiction of Iris Murdoch, Margaret Drabble and AS Byatt, p.11

[4] Suhasini Tapaswi Feminine Sensibility in the Novels of Margaret Drabble, p.33

[5] Pat Williams, 'The Sisters Drabble', The Sunday Times Magazine, 6 August 1967, pp.12-15

[6] Peter E. Firchow , 'Rosamund's Complaint: ‘Margaret Drabble's The Millstone (1966)’ in Robert K. Morris ed. Old Lines, New Forces: Essays on the Contemporary British Novel, 1960-1970, p.96