![The Cavafy Variations The Cavafy Variations]()

Poetry is what gets lost in translation. – Robert Frost

Recently I was asked to review The Cavafy Variations by Ian Parks for Elsewhere. As I knew nothing of Cavafy I decided to do my customary research and soon realised that there was no way I could do the thing justice in only five hundred words. This monster of a post it what I ended up with—basically it’s my working notes and quotes all tidied up and typed up and yet I only feel like I’ve scratched the surface. Phillipson’s C.P. Cavafy Historical Poems took him twenty-five years to write. This was the best I could do in a week.

***

Translation is a bugger; Auden says as much in his introduction to The Complete Poems of Cavafy where he waxes lyrical on all the things that are either lost completely—or much diluted—when one attempts to translate a poem from one language to another and yet he notes:

I have read translations of Cavafy made by many different hands, but every one of them was immediately recognizable as a poem by Cavafy; nobody else could possibly have written it. […] What is it then that survives translation and excites?

[…]

Reading any poem of his, I feel: “This reveals a person with a unique perspective on the world.” That the speech of self-disclosure should be translatable seems to me very odd, but I am convinced that it is. The conclusion I draw is that the only quality which all human beings without exception possess is uniqueness: any characteristic, on the other hand, which one individual can be recognized as having in common with another, like red hair or the English language, implies the existence of other individual qualities which this classification excludes.

One would have thought that the above could be said of a great many writers: Kafka, Beckett, Brautigan, Bukowski; pick up a book by any one of them and within a few lines you know precisely who you’re reading. So what’s so special about Cavafy?

On the surface nothing much. In fact to the casual observer he could well come across as a decidedly ordinary poet, even a bad poet. Much of his subject matter is obscure unless you have a particular interest in ancient Greece; he sidesteps most common poetic techniques—you’ll be hard pressed to find a simile or a metaphor in any of his poems, particularly the later ones—and yet he clearly has his admirers. One of these was the Nobel laureate Giorgos Seferis who, during a 1946 lecture at Athens, had this to say about Cavafy’s life:

“Cavafy stands at the boundary where poetry strips herself in order to become prose,” he remarked, although not without admiration. “He is the most anti-poetic (or a-poetic) poet I know.”[1]

Daniel Mendelsohn’s article on Cavafy for The New York Times is entitled: ‘As Good as Great Poetry Gets’ and in his article for The New Yorker, ‘Man with a Past’, Dan Chiasson refers to Cavafy as “the greatest Greek poet since antiquity;”[2] high praise indeed. There’s a problem though: A.E. Stallings notes, in her essay for the Poetry Foundation, ‘More Cavafy’, that “Cavafy is without doubt the most translated and retranslated of modern Greek poets—perhaps among the most translated of foreign poets into English period”—but despite what Auden says it appears that some translators do Cavafy a disservice. To illustrate Stallings quotes from a comment made by Reginald Shepherd in an article by Rigoberto González, ‘In Praise of Cavafy’:

All the translations I’ve read make Cavafy sound like prose broken into lines—well-written, sensitive, insightful prose, but prose nonetheless. Reading the introductions to the translations and other work about Cavafy, I understand that Cavafy was an obsessive poetic craftsman, obsessively revising and refining each line. I also understand that much of the verbal power of his poems comes from his mingling of the refined and stilted Greek called Katharevusa, inherited from the Byzantines, which was the standard literary language of his time, with Demotic, vernacular, spoken Greek, which was not considered acceptable for literature. None of this comes across in any of the translations I have read. This absence, combined with the relative paucity of figurative language—as I recall, Cavafy has vivid imagery, but few metaphors and similes—contributes to the prosaic feel of his poetry in the translations I’ve read.

So, chopped-up prose or great poetry? And although oft quoted just because Auden said what he said does that make it true? I can find no evidence that Auden could read Greek so how qualified was he to say what was a good or a bad translation? Dan Chiasson on the other hand concluded that "Cavafy survives translation relatively unscathed” although he qualifies this remark by adding, that “should not imply that he has survived all translations equally intact.”[3] And from all accounts he can read Greek.

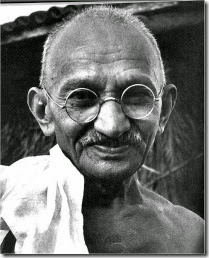

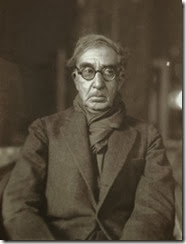

E.M. Forster, who got to know him in his fifties and his first champion in the west, famously described Cavafy as “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.”[4] Giorgos Seferis said that “outside his poems Cavafy does not exist.”[5] Who then was C.P. Cavafy?

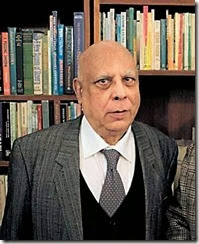

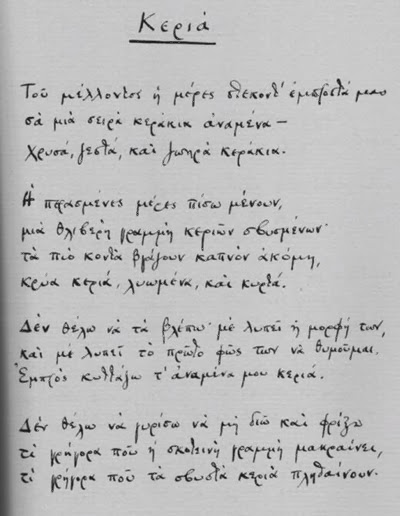

![Cavafy Cavafy]() Constantine Petrou Photiades Cavafy (as he wanted the family name to be spelled in English) was born in Alexandria, Egypt on 29 April 1863 to Greek parents; he lived most of his life there and died there exactly seventy years later. Both parents were natives of Constantinople (now Istanbul) and Cavafy was proud of his heritage; he regarded Constantinople as his spiritual home although he actually only spent a relatively short period of time living in the city. The Cavafy family flourished in Alexandria both financially and socially but two years after the death of Cavafy’s father in 1870 they were forced to move to England to stay with his uncles living between Liverpool and London; Constantine would have been nine years old at the time of the move. Naturally he attended school in England and consequentially, it’s been reported, spoke Greek with a slight English inflection for the rest of his life. During this time he became acquainted with more British poetry than he might have had he remained in Egypt or moved to Greece and this clearly affected his early verse writing; of the Victoria poets Browning especially helped him develop his technique of dramatic monologue although he also owes a debt of thanks to two French poetic movements, Parnassianism and Symbolism as well as the Decadent and Aesthetic movements.

Constantine Petrou Photiades Cavafy (as he wanted the family name to be spelled in English) was born in Alexandria, Egypt on 29 April 1863 to Greek parents; he lived most of his life there and died there exactly seventy years later. Both parents were natives of Constantinople (now Istanbul) and Cavafy was proud of his heritage; he regarded Constantinople as his spiritual home although he actually only spent a relatively short period of time living in the city. The Cavafy family flourished in Alexandria both financially and socially but two years after the death of Cavafy’s father in 1870 they were forced to move to England to stay with his uncles living between Liverpool and London; Constantine would have been nine years old at the time of the move. Naturally he attended school in England and consequentially, it’s been reported, spoke Greek with a slight English inflection for the rest of his life. During this time he became acquainted with more British poetry than he might have had he remained in Egypt or moved to Greece and this clearly affected his early verse writing; of the Victoria poets Browning especially helped him develop his technique of dramatic monologue although he also owes a debt of thanks to two French poetic movements, Parnassianism and Symbolism as well as the Decadent and Aesthetic movements.

When Cavafy was fourteen they returned home where he finished high school and, with the exception of a three-year sojourn to Constantinople from 1882 to 1885 following the British bombardment of Alexandria, Cavafy would never live anywhere else, although he did take holidays in Greece and it was to Greece that he travelled in 1932 in order undergo a tracheotomy for cancer of the throat. It was, however, during that initial extended stay in Greece that his passion with history was kindled—at the age of fifteen he began compiling an historical dictionary—and that fire never went out. In fact in later years he described himself as “not a poet only” but a “poet-historian”.[6] The term ‘historian’ needs to be viewed in a wider context than one might normally think of the word; everything that has passed has passed into history; we are the machines of history. Greece was also important for the young Cavafy because it was there from all accounts he had his first homosexual experiences.

For most of his life Cavafy worked mornings as a “permanently temporary minor colonial civil servant”,[7] to quote G.P. Savidis, in the wonderfully-named Third Circle of Irrigation (very Dante-cum-Kafkaesque); in the afternoons he played the stock market—not unsuccessfully—and in the evenings he indulged his sexual proclivities once he had done keeping his overbearing mother company. Following the death of their mothers he lived with two of his brothers until they left—one moved to Cairo, the other went travelling and simply never returned—and so from 1908 until his death in 1933 he lived alone in a fusty flat above a brothel in one of the ![Oscar-Wilde Oscar-Wilde]() city’s poorer quarters. He was a famously private man—one of his friends described him as “almost pathologically timid”[8]—and yet his poetry became increasingly homoerotic as time went by and this at a time when people were, let’s just say, nowhere near as accepting or even as tolerant as they are nowadays; not the way to keep under the radar. Only in 1895 Oscar Wilde had been sentenced to two years’ hard labour, the poem 'Two Loves' by Lord Alfred Douglas, being cited by the prosecution, and if anything it was Wilde’s response to the prosecution’s question, “What is ‘the love that dare not speak its name’?” that probably sealed his fate. Perhaps it’s just as well that Cavafy didn’t remain in Britain. That said:

city’s poorer quarters. He was a famously private man—one of his friends described him as “almost pathologically timid”[8]—and yet his poetry became increasingly homoerotic as time went by and this at a time when people were, let’s just say, nowhere near as accepting or even as tolerant as they are nowadays; not the way to keep under the radar. Only in 1895 Oscar Wilde had been sentenced to two years’ hard labour, the poem 'Two Loves' by Lord Alfred Douglas, being cited by the prosecution, and if anything it was Wilde’s response to the prosecution’s question, “What is ‘the love that dare not speak its name’?” that probably sealed his fate. Perhaps it’s just as well that Cavafy didn’t remain in Britain. That said:

Before 1914, in his city and particularly within his class, there prevailed an imitation of Victorian morality―of the most narrow-minded, anti-aesthetic kind. In such an atmosphere, a scandal such as that of Oscar Wilde could easily have been repeated. Cavafy ran the risk of seeing his relatives’ homes closed to him, of being ostracized, of no longer being greeted on the street, or even―and I have in mind specific facts―being banished from the city he loved. And yet he dared.[9]

And he nearly came a cropper too in 1924. At the time he circulated a poem entitled ‘Before Time Altered Them’ which opens:

They were full of sadness at their parting.

That wasn’t what they themselves wanted: it was circumstances.

The need to earn a living forced one of them

to go far away—New York or Canada.

[Edmund Keeley/Philip Sherrard]

In Cavafy’s original Greek, the initial upsilon of Iorki [Νέα Υόρκη, New York] is marked with a smooth breathing, as it should be. A journalist subsequently noted that Cavafy’s orthography differed from that of fellow-journalist and physician Socrates Lagoudakis, who seems to have spelled Iorki with a rough breathing. Or perhaps the journalist reported Cavafy’s mockery of Lagoudakis’s substandard English—accounts vary. All parties agree that Lagoudakis took offense and began to devote several of the signature character profiles that he regularly disseminated in the press to Cavafy, whom he apparently denounced as “another Wilde.” Though there were rumours of an impending lawsuit, the poet did not respond.[10]

Greeks feel passionate about many things but grammar appears to rank near the top of the list. Luckily it all blew over.

Homoerotic, although technically accurate, is really not the right word though. Just because Cavafy writes about sex doesn’t mean his work is erotic in the same way you might think of the writings of Anaïs Nin. He doesn’t apologise but neither does he stand on a soapbox. “[I]n his whole lifetime he never gave out one of his ‘dangerous’ poems more than once to the general public and to periodicals.”[11] He learned to live with himself but not perhaps to love himself.

Cavafy started publishing poems and articles in Greek following his second return to Alexandria. His first published text was an article entitled ‘Coral, from a Mythological Viewpoint’ in the newspaper Constantinople on 3 January 1886 but he never found much success; his early poetry was mediocre. In fact it wasn’t until his late-forties that he found his voice. Cavafy is reported to have called himself, late in life, a “poet of old age”[12], comparing himself with Anatole France who “wrote his colossal work after the age of forty-five.”[13] It was at this time he performed what he called a “Philosophical Scrutiny” of his writing. Basically everything in his life came to a head:

This unsparing (if, typically, not unforgiving) self-examination was the portal to the poet’s mature period, one in which the tripartite division that he had once used to categorize his work—into “philosophical” (by which he meant provocative of reflection), “historical,” and “sensual” poems[14]—began to disintegrate. The enriched and newly confident sense of himself as a Greek and as a man of letters that resulted from the intellectual crisis of the 1890s seems to have resulted in some kind of reconciliation with his homosexual nature, too. (The death of his mother might, in its own way, have been liberating in this respect.)

[I]t is no accident that Cavafy himself dated this period to the year 1911—the year in which he published ‘Dangerous [Thoughts],’ the first of his poems that situated homoerotic content in an ancient setting.[15]

Of course a term like ‘sensual’ is a broad one. For example, Cavafy classified ‘In Church’ as a sensual poem because he’s focusing on the sensory experiences whilst being in a church:

In Church

I love the church—its liturgical fans,

the silver of the vessels, its candlesticks,

the lights, the icons, the pulpit.

When I enter there, in a church of the Greeks,

with its fragrances of incense,

amid the liturgical voices and harmonies,

the majestic presence of the priests

and the stately rhythm of their every move—

most resplendent in the finery of their vestments—

my mind travels to the great glories of our race,

to our illustrious Byzantine past.

[Evangelos Sachperoglou]

Unlike France, Cavafy’s output could not be described as colossal. He often revised poems over years—“he never wrote a single poem uninterruptedly from beginning to end”[16]—and only left one hundred and fifty-four completed poems at the time of his death, the so-called canon. Indeed he repudiated—his word—most of the poems written prior to this although he did try to salvage as many as he could:

My method of procedure for this Philosophical Scrutiny may be either by taking the poems one by one and settling them at once—following the lists and ticking each on the list as it is finished, or effacing it if vowed to destruction: or by considering them first attentively, reporting on them, making a batch of the reports, and afterwards working on them on the basis and in the sequence of the batch: that is the method of procedure of the Emendatory Work…[17]

Cavafy writes about the liminal and the peripheral whether in geographical terms or temporal. Although he’s mostly writing in the present tense the past is continually present and in the past the present is waiting. “To me,” he writes in 1906, “the immediate impression is never a starting point for work. The impression has got to falsify itself with time, without my having to falsify it.”[18] And in 1902: “Do Truth and Falsehood really exist? Or, is there only New and Old—and the False is simply the old age of Truth?”[19]

People are often in a state of transition within his poems and this is nowhere better expressed than in his perhaps best-known work, ‘Candles’—an old poem from 1893, one of the twenty-four which survived the cull—in which into the future stretches a line of lit candles; behind us is a similar line of extinguished candles; a simple, yet elegant metaphor. In later years he said that the poem was “one of the best things I ever wrote”[20] and added:

What a deceitful thing Art can be, when you want to apply sincerity. You sit down and write—often speculatively—about emotions, and then, over time, you doubt yourself. I wrote ‘Candles,’ ‘The Souls of Old Men’ and ‘An Old Man’ about old age. Advancing towards old (or middle) age, I discovered that this last poem of mine does not contain a correct evaluation. ‘The Souls of Old Men’ I still think correct; but when I reach seventy years I might find it wanting too. ‘Candles’ I hope is safe.[21]

![Cavafy Candles Cavafy Candles]()

Manuscript of the poem ‘Candles’

This is clearly a poem one would classify as philosophical but the distinctions are not always as clear. One should not assume that a piece set in the past cannot also deal with philosophical issues (e.g. ‘Nero’s Deadline’) or sensual (‘The God Abandons Antony’).

All of Cavafy’s poems have either a personal or historical source. In an illuminating article, ‘Cavafy's Technique of Inspiration’, Kōnstantinos Dēmaras discusses what he sees as Cavafy’s method: “[I]t is the reconstruction, often voluntary, of real or imaginary scenes from the poet’s personal life or from history.” He seems far more interested in remembering than in experiencing, reliving rather than living:

I’ve Brought to Art

I sit in a mood of reverie.

I brought to Art desires and sensations:

things half-glimpsed,

faces or lines, certain indistinct memories

of unfulfilled love affairs. Let me submit to Art:

Art knows how to shape forms of Beauty,

almost imperceptibly completing life,

blending impressions, blending day with day.

[Edmund Keeley/Philip Sherrard]

Often these memories are reimagined and set in the distant past of the distant city of Alexandria, the place where he came to embrace his true nature:

Delight of flesh between

those half opened clothes:

quick baring of flesh―the vision of it

that has crossed twenty-six years

and comes to rest now in this poetry.

[from ‘Comes to Rest’ | Edmund Keeley/Philip Sherrard]

[A]s the home of his “life’s memories,” Alexandria soon became the primary source for poem after poem that invoked, through memory, the more or less secret erotic experience of his youth that he decided to reveal with growing candour and verisimilitude. And by 1910, three years after his ambivalent note and after he had settled into the Rue Lepsius apartment for the rest of his life, signalling his accommodation with the city, Alexandria began to be transformed in the central “historical” myth of his mature work.[22]

Although early on in his career he submitted his poetry to magazines this fell off and he chose to self-publish, distributing his poems to specific people who he hoped would appreciate them:

Those poems that Cavafy allowed to be printed during his lifetime were distributed to a restricted audience. He would pass them out as they seemed ready to his trusted friends first in sample pamphlets, then as broadsheets and offprints, these usually gathered into folders that could be supplemented regularly, some of the older poems revised by hand now and then, a few suppressed. And when the clips in the folders could no longer bear the burden of additional poems, the poet would withdraw some and have them sewn into booklets.[23]

His work was after all revolutionary: he’s most definitely an anti-Romantic; nature and the countryside are rarely mentioned in his poems and never its focus (see ‘Lovely White Flowers’). Like Baudelaire, whose work he admired, the setting of Cavafy’s world is the city. The Chilean Nicanor Parra is known as the father of anti-poetry—his first collection of antipoems appeared in 1954—but Cavafy was doing for Greek poetry exactly what Parra did years later for Spanish:

That he rejected the music of the demotic fifteen-syllable verse, that he completely ignored the folk song, that he banished compound words and current poetic images from his poetry … constituted, of course, a revolution.[24]

Now, and especially in translation, it’s hard to see what all the fuss was about especially since he was hardly read but word obviously spread:

[W]hile the older writers of the preceding generation disapproved violently of Cavafy, the younger writers of the period turned their attention to him with affection. […] Agras spoke, in discussing his work, “about his contemptuous scepticism with regard to every faith.” Thyros affirmed that Cavafy “believed in negation.” The scepticism, the irony of Cavafy were the subjects that attracted criticism. As always occurs with great writing, the current generation was reflected in the work of Cavafy and recognised itself in it.[25]

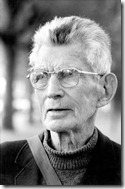

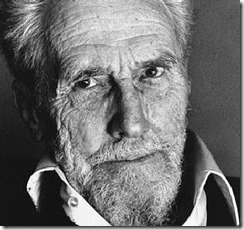

![cavafy-old-eps-copy-2 cavafy-old-eps-copy-2]() The reason he chose not to seek publication of his work during his lifetime has been debated because there certainly appears to have been a growing demand. The answer may lie in a remark Giorgos Seferis made; he said that after about 1910 Cavafy’s work “should be read and judged not as a series of separate poems, but as one and the same poem.”[26] Seferis saw Cavafy’s perception of his oeuvre as a life-long work in progress, still incomplete at his death. While in Athens being treated for throat cancer he apparently said he had twenty-five poems still to complete. These, and others, remained hidden within the Cavafy archives until unearthed by Cavafy’s editor, George Savidis, in 1961.

The reason he chose not to seek publication of his work during his lifetime has been debated because there certainly appears to have been a growing demand. The answer may lie in a remark Giorgos Seferis made; he said that after about 1910 Cavafy’s work “should be read and judged not as a series of separate poems, but as one and the same poem.”[26] Seferis saw Cavafy’s perception of his oeuvre as a life-long work in progress, still incomplete at his death. While in Athens being treated for throat cancer he apparently said he had twenty-five poems still to complete. These, and others, remained hidden within the Cavafy archives until unearthed by Cavafy’s editor, George Savidis, in 1961.

Much has been written about the problems translators face when approaching the work of Cavafy. The first is the fact that he wrote in both Katharevousa, a conservative form of the Modern Greek language conceived in the early 19th century as a compromise between Ancient Greek and Demotic Greek, and Demotic. As a Scot the best way I can imagine this is to conceive a poet who wrote in both Lallans (what Hugh MacDiarmid called synthetic Scots) and Glaswegian. (To get the idea see the note on ‘Days of 1909, ’10, ’11’ below.)

Ian Parks, whose own poetry is known for being “spare, lyrical, memorable and intense”[27] and who is probably best known as a love poet (he has apparently been described by Chiron Review as “the finest love poet of his generation”[28]), is the latest to have a crack at presenting Cavafy’s poetry to an English-speaking audience. It’s a modest approach, only ten poems, but an impressive one nevertheless. The Cavafy Variations comprises the following:

Candles [1899]

The City [1910]

Unfaithfulness [1904]

The Watchman [1900]

As Kleitos Lies Dying [1926]

The Deadline [1918]

Prayer [1898]

The First Step [1899]

The God Abandons Antony [1911]

If Possible [1913] (Usually entitled ‘As Much as You Can’)

The dates above are the earliest publication dates; ‘published’ in the Cavafian sense that is. It’s not quite a ‘Best of’ as a number of the better known poems—‘Walls’, ‘Ithaca’ and ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’—are missing but the poems do provide examples from all points of his career. As a sampler then it’s fine. If nothing here grabs you then he’s probably not the poet for you.

Variations are common in music—just think of theEnigma Variations or Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini or even the theme to The South Bank Show from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s album Variations—but not so much in poetry: we would probably talk of “loose translations” and a good example of this is the collection The Jaguar’s Dreamby the Australian poet John Kinsella. There’s nothing in the booklet to tell us whether Parks went back to the original Greek or simply reimagined, to use a popular buzzword, the poems based on readings of the various existing translations. Parks is a Yorkshire lad, son of a miner no less (hard not to think of Stand Up, Nigel Barton and Monty Python’s‘Northern Playwright’ sketch) and they’re not big Greek speakers in Mexborough. Being no Greek scholar myself and having read enough over the last few days about the problems facing translators of Cavafy’s poetry, the only thing I can do is compare these new poems to the translations available to me and see whether Parks’s poems stand in their own right. The rhymes and rhythms of especially the earlier poems will be lost—that’s inevitable—but has “the tone of voice” that Auden spoke of survived? Let’s look at one poem in detail, the second half of ‘The City’ (you don’t need to read them all):

You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore.

This city will always pursue you. You will walk

the same streets, grow old in the same neighbourhoods,

will turn grey in these same houses.

You will always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

there is no ship for you, there is no road.

As you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

you’ve destroyed it everywhere else in the world.

[Edmund Keeley/Philip Sherrard]

You shall not find new places; other seas

you shall not find. The place shall follow you.

And you shall walk the same familiar streets,

and you shall age in the same neighbourhood,

and whiten in these same houses. Ever this place

shall you arrive at. There is neither ship,

nor road, for you, to bring you otherwhere.

As here, in this small nook, you wrecked your life,

even so you spoilt it over all the earth.

[John Cavafy, the poet’s brother and his first translator]

You will find no other place, no other shores.

This city will possess you, and you’ll wander the same

streets. In these same neighbourhoods you’ll grow old;

in these same houses you’ll turn grey.

Always you’ll return to this city. Don’t even hope for another.

There’s no boat for you, there’s no other way out.

In the way you’ve destroyed your life here,

in this little corner, you’ve destroyed it everywhere else.

[Stratis Haviaras]

Fresh lands you shall not find, you shall not find other seas.

The city shall ever follow you.

In streets you shall wander that are the same streets and

grow old in quarters that are the same

and among these very same houses you shall turn grey.

You shall always be returning to the city. Hope not;

there is no ship to take you to other lands, there is no road.

You have so spoiled your life here in this tiny corner

that you have ruined it in all the world.

[George Vlassopoulos]

You will find no new lands, you will find no other seas.

The city will follow you. You will roam the same

streets. And you will age in the same neighbourhoods;

and you will grow grey in these same houses.

Always you will arrive in this city. Do not hope for any other –

There is no ship for you, there is no road.

As you have destroyed your life here

in this little corner, you have ruined it in the entire world.

[Rae Dalven]

You’ll find no new places, you won’t find other shores.

The city will follow you. The streets in which you pace

will be the same, you’ll haunt the same familiar places,

and inside those same houses you’ll grow old.

You’ll always end up in this city. Don’t bother to hope

for a ship, a route, to take you somewhere else; they don’t exist.

Just as you’ve destroyed your life, here in this

small corner, so you’ve wasted it through all the world.

[Donald Mendelshon]

Any new lands you will not find; you'll find no other seas.

The city will be following you. In the same streets

you'll wander. And in the same neighbourhoods you'll age,

and in these same houses you will grow grey.

Always in this same city you'll arrive. For elsewhere—do not hope

There is no ship for you, there is no road.

Just as you've wasted your life here,

in this tiny niche, in the entire world you've ruined it.

[Evangelos Sachperoglou]

You will not find new lands, you will not find other seas.

The city will follow you. You will roam

the same streets. And you will grow old in the same neighbourhood,

and your hair will turn white in the same houses.

You will always arrive in this city. Don’t hope for elsewhere –

there is no ship for you, there is no road.

As you have wasted your life here,

in this small corner, so you have ruined it on the whole earth.

[Aliki Barnstone]

There’s no new land, my friend, no

New sea; for the city will follow you,

In the same streets you’ll wander endlessly,

The same mental suburbs slip from youth to age,

In the same house go white at last —

The city is a cage.

No other places, always this

Your earthly landfall, and no ship exists

To take you from yourself. Ah! don’t you see Just as you’ve ruined your life in this

One plot of ground you’ve ruined its worth

Everywhere now — over the whole earth?

[Lawrence Durrell]

You will not find other places, you will not find other seas.

The city will follow you. All roads you walk

will be these roads. And you will age in these same neighbourhoods;

and in these same houses you will go grey.

Always you will end up in this city. For you

there is no boat—abandon hope of that—no road to other things.

The way you've botched your life here, in this small corner,

makes for your ruin everywhere on earth.

[Theoharis Constantine Theoharis]

There is no other city, no new place.

This lost metropolis will track you down.

Age will make you tread the empty streets,

frequent the shabby regions every night –

hidden quarters, hidden houses all the same.

There are no roads to help you escape,

no ships to speed you on your way.

The damage that you did will follow you.

You’ll take this city with you when you go.

[Ian Parks]

Καινούριους τόπους δεν θα βρεις, δεν θάβρεις άλλες θάλασσες.

Η πόλις θα σε ακολουθεί. Στους δρόμους θα γυρνάς

τους ίδιους. Και στες γειτονιές τες ίδιες θα γερνάς•

και μες στα ίδια σπίτια αυτά θ’ ασπρίζεις.

Πάντα στην πόλι αυτή θα φθάνεις. Για τα αλλού — μη ελπίζεις—

δεν έχει πλοίο για σε, δεν έχει οδό.

Έτσι που τη ζωή σου ρήμαξες εδώ

στην κώχη τούτη την μικρή, σ’ όλην την γη την χάλασες.

[C.P. Cavafy]

![Alexandria Alexandria]()

Alexandria

I’ve left Cavafy’s original to the end so you can compare the shape of the Greek with Parks’s variation. By all means paste the text into Google Translate and see what you make of it. It’s obvious simply glancing at the two that he’s taken liberties with the text. I was puzzled by his choice of ‘lost metropolis’. No one else uses that expression and the Greek ‘Η πόλις θα σε ακολουθεί’ translates simply as ‘The city will follow you’; I translated the English phrase back into Greek and the two sentences match perfectly. So why the change? Perhaps because Cavafy’s early poems often included rhymes—frequently homophonous and the unrhymed poems usually follow strict syllabic patterns normally varying between eleven and sixteen syllable lines—and as direct transliteration would cause these to vanish the translator must compensate when he can. Of this poem, in an earlier draft admittedly, Cavafy writes:

‘In the Same City’ is from one point of view perfect. The versification and chiefly the rhymes are faultless. Out of the seven rhymes on which this poem is built, 3 are identical in sound and 1 has the accent on the antepenultimate.[29]

In his version Parks also expands the sentence ‘The city will follow you’ to include ‘track you down’ rather than simply ‘follow’ because ‘ακολουθώ’ has the connotation of ‘come after as a consequence of previous events’. A nice catch.

In the last line Google didn’t like the word ‘κώχη’ so I looked it up elsewhere and was given the translation ‘nook’. A nook is a small thing, not a metropolis and so although ‘lost metropolis’ has a nice sound to it, it works against what the poet is saying later, that the mistakes the narrator’s made in this small corner of the world will haunt him wherever in the big bad world he finds himself. I can see why Parks might use the word ‘metropolis’ because the word for ‘city’ in Greek is polis. Although in later works he glorified Alexandria back in 1907, Cavafy did indeed consider it a small corner of the world. In a note he wrote:

I have grown accustomed to Alexandria, and it is quite probable that even if I were rich I would stay here. But, despite this, how it constricts me. What an impediment, what a burden a small town is—what an absence of freedom.

I would stay here (then again I am not completely sure if I would remain) because it is like a homeland, because it is associated with the memories of my life.

Yet, how necessary for a man like me—so particular—is a big city.

Londres [London], for instance…[30]

And in an early draft of ‘The City’ he really doesn’t pull his punches:

I hate the people here and they hate me,

here where I’ve lived all my life.[31]

Having read quite a bit about Cavafy’s life I can see why Parks might’ve included the lines:

frequent the shabby regions every night –

hidden quarters, hidden houses all the same.

These were the parts of the city Cavafy slunk to at night and they reflect the (at times) overbearing disgust he felt at the time of writing. It was only in his forties that he became more comfortable with his sexual orientation. In the early years he was clearly ashamed of his lifestyle. He frequented the quartier around the Rue d'Anastsi, where it was easy to find poor young Greek men who would provide sexual favours in return for small amount of cash and bribed his servants to ruffle up his sheets at night so his mother wouldn’t realize he’d not been home.

One friend recalled … that he would return from his exploits and write, in large letters on a piece of paper, “I swear I won’t do it again.”[32]

He did, of course.

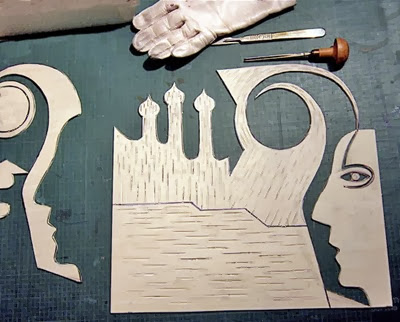

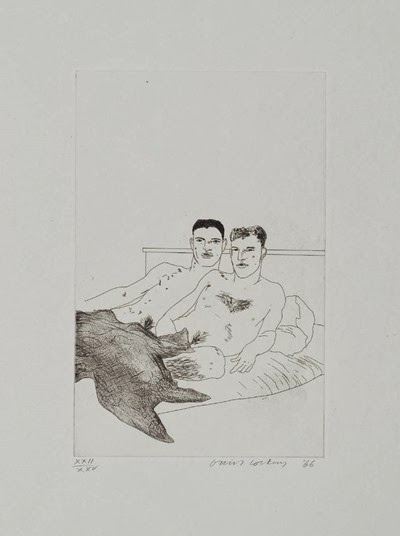

![Cavafy Hockney Cavafy Hockney]()

David Hockney, ‘The Beginning’

fromIllustrations for Fourteen Poems by C,P Cavafy (1966)

Parks misses out on the “abandon hope” sentiment. It could easily have been incorporated in the line ‘There are no roads, [no hope of] escape’. Although the writer’s hopelessness is implied I wonder if there’s a reason Cavafy chose to underline it? He says ‘do not hope’ or something close to that but when Theoharis uses ‘abandon hope’ it’s hard not to think of the words ‘Abandon all hope, you who enter here’ or am I reading between the lines?

‘Age will make you tread the empty streets’ sounds awkward. The notion of gravitating to familiar haunts is missing. Durrell has the right idea but his language is every bit as awkward: ‘The same mental suburbs slip from youth to age.’ The city is a mental construct. Cavafy rarely writes in his poems about the Alexandria he could see out of his window; it was either the city he remembered or one he imagined. Usually a bit of both. Durrell hits the nail on the head though when he writes “no ship exists / To take you from yourself.” Of course he could be accused of trying to interpret the poem for his reader and that’s always a danger in any translation and Parks can also be accused of that; it must be hard not to. That aside what he has produced is an eminently readable “variation” of the poem. It flows like English. The broad strokes are still intact. Maybe some of the fine details have been lost or traded but as André Aciman points out in his lengthy comparison of various translations of ‘The City’:

What never ceases to baffle anyone studying the many translations of this one poem is that each is so different. And yet no one gets it quite right either—even though, on rereading this poem for the nth time, it is really quite a simple and straightforward poem. Why so many versions? Why the need for yet one more go at it?[33]

Why indeed? Of the versions above it might be an idea to dwell on the translation by his brother. Admittedly English was his second language but he and Constantine corresponded often (translations of various letters can be found here) and they frequently discussed the nuances of English. Specific examples can be found here, here and especially here where John discusses the proper use of ‘shall’ as opposed to ‘will’. Is his the most faithful version? Faithful to what? The text or the spirit? A response to Aciman’s article by Eric Dean Wilson of Archipelago Books can be found here.

Of the ten poems chosen by Parks it was the philosophical that chimed with me from the line of lit and extinguished candles in ‘Candles’ through the damage that follows us in ‘The City’ to the life that becomes nothing more than a “tedious acquaintance” in ‘If Possible’. All these focus on a sense of belatedness as do the historical because, inevitably, the past is lost to us:

It’s not the time to have regrets,

to brood upon the glories of your past

or curse the good luck you once had

now that it’s faltering, running low.

[from ‘The God Abandons Antony’]

Gods abound—both Christian and pagan—but they’re impotent:

the idol is impervious;

it doesn’t hear or care

[from ‘As Kleitos Lies Dying’]

The icon hears unblinking, powerless

[from ‘Prayer’]

or insensitive as in the case of ‘The God Abandons Antony’. ‘Unfaithfulness’ and ‘The Deadline’.

It’s the march of history which overpowers all. The prophecy in ‘The Deadline’ reminded me of what the witches in Macbeth had to say aboutBirnam Wood. When Nero is warned by Apollo, “Beware the age of seventy-three,” he assumes he has time. With “the deadline more than thirty years away” he never imagines he might have anything to fear from a seventy-three-year-old man.

‘Candles’ is the perfect poem to open this grouping because it is exemplifies the betwixtness inherent in Cavafy’s poetry, trapped between a squandered past and an uncertain future. The Watchman in the poem of the same name, however, “knows the waiting has to end”:

Much will be said in the halls of state

About what’s to be gained and what’s to lose.

The secret is to listen, nod, and not believe.

The one thing man learns from history, however, is that man learns nothing from history:

At each street corner, looking back

I see myself among the ruined squares,

the cafés and the harbour bars,

repeating the identical mistakes.

[from ‘The City’]

It will most likely be the historical poems of Cavafy that people struggle with primarily because his interests are the backwaters of Greek history.

The chief periods in which Cavafy sets his historical poems are the Hellenistic (fourth to first centuries BC), the Roman (first century BC to fourth century AD), and the late Byzantine (eleventh to fourteenth centuries)

[...]

For most people who study Ancient History, the Greek history they learn about ends with the death of Alexander the Great [in 323 BC].[34]

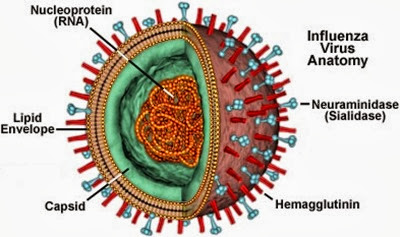

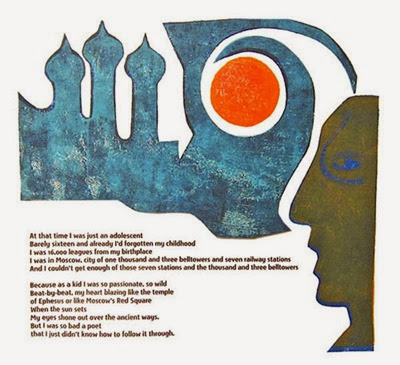

![Pythia Aegeus Themis Delphi[1] Pythia Aegeus Themis Delphi[1]]() Thankfully the poems that Parks chooses to include in his booklet are more accessible. We know who Mark Antony and Nero are and we’ve heard of Troy and the oracle of Delphi. I knew about Mount Olympus but Mount Arachnaion was new to me; archaeologists have found remains of altars to Zeus and Hera there. It’s not a big issue because the point the poem has to make, that no one is irreplaceable (even the gods have been replaced) and there’s always someone ready to step into our shoes. That is as relevant today and it was when the fires of those altars were lit for the first time.

Thankfully the poems that Parks chooses to include in his booklet are more accessible. We know who Mark Antony and Nero are and we’ve heard of Troy and the oracle of Delphi. I knew about Mount Olympus but Mount Arachnaion was new to me; archaeologists have found remains of altars to Zeus and Hera there. It’s not a big issue because the point the poem has to make, that no one is irreplaceable (even the gods have been replaced) and there’s always someone ready to step into our shoes. That is as relevant today and it was when the fires of those altars were lit for the first time.

I’ve mentioned the homoerotic content of Cavafy’s work but there’re no good examples of it The Cavafy Variations and little sensual even apart from a few lines in ‘The God Abandons Antony’ and even there it’s a looking back with regret as shown in the quote above. The god is not named and some have assumed it to be Dionysus, the god of the grape harvest, winemaking and wine, of ritual madness and ecstasy:

The poem refers to Plutarch's story of how Antony, besieged in Alexandria by Octavian, heard the sounds of instruments and voices of a procession making its way through the city, then passing out; the god Bacchus (Dionysus), Antony's protector, was deserting him. – Wikipedia

The above is not wrong. It’s a starting point but Edmund Keeley has his own thoughts on the subject:

Cavafy … cunningly replaced Plutarch’s Dionysus and Shakespeare’s Hercules by the city itself as the god who abandons Antony in his moment of ultimate defeat after Actium, the god’s departure signalled by a sudden passing of an invisible procession of musicians. The poem suggests that Alexandria had a godlike power to move the minds of mortals with poetic conceptions of itself, at least in those they city finds worthy to receive this divine gift—a gift that can be withdrawn as well as granted.[35]

It is a poem that resonates with ‘The City’. In both instances a man’s life is in ruins. Cavafy uses that exact metaphor in the first stanza of ‘The City’ but it’s implied too in ‘The God Abandons Antony’.

But there’s nothing here that, to my mind, warrants the title “erotic poet” as you’ll find him often referred to online. There are young men, Evmenius in ‘The First Step’ and Kleitos in ‘As Kleitos Lies Dying’ but there’s nothing like this:

One Night

The room was cheap and sordid,

hidden above the suspect taverna.

From the window you could see the alley,

dirty and narrow. From below

came the voices of workmen

playing cards, enjoying themselves.

And there on that common, humble bed

I had love’s body, had those intoxicating lips,

red and sensual,

red lips of such intoxication

that now as I write, after so many years,

in my lonely house, I’m drunk with passion again.

[Edmund Keeley/Philip Sherrard]

Of course if you came upon the poem by chance and knew nothing of Cavafy there’s you might easily think the subject of the poem is a woman (besides not every poem by Cavafy is about homosexuals); this is commonplace in the poems prior to 1919. This later one makes its point clearer:

Days of 1909, ’10, and ’11

He was the son of a much put-upon, impoverished

sailor (from an island in the Aegean Sea).

He worked at a blacksmith’s. He wore threadbare clothes;

his workshoes split apart, the wretched things.

His hands were completely grimed with rust and oil.

Evenings, when he was closing up the shop,

if there was anything he was really longing for,

some tie that cost a little bit of money,

some tie that was just right for a Sunday,

or if in a shop window he’d seen and yearned for

some beautiful shirt in mauve:

one or two shillings is what he’d sell his body for.

I ask myself whether in antique times

glorious Alexandria possessed a youth more beauteous, [36]

a lad more perfect than he—for all that he was lost:

for of course there never was a statue or portrait of him;

thrown into a blacksmith’s poor old shop,

he was quickly spoiled by the arduous work,

the common debauchery, so ruinous.

[Daniel Mendelshon] [published in 1928]

But it’s still not exactly titillating is it? Or was I expecting pornographic? All his poems are post-coital. He’s not particularly interested in the sex. But then he’s not exactly interested in love either. He’s interested in memories which are the building blocks of the imagination:

The aging of my body and face

is a wound from a horrible knife.

I'm not resigned to it at all.

O Art of Poetry, I resort to you

who know a little about medicines:

attempts to deaden pain through Imagination and Language.

[from ‘Melancholy of Jason Kleander, Poet in Kommagini, A.D. 595’]

![Old Men Old Men]()

from Shades of Love: Photographs Inspired by the Poems of C. P. Cavafy

Dimitris Yeros

I was so struck by this notion that I ended up writing my own poem, ‘Not Now’ which begins:

Now is no use to poets.

It has

its uses

but best leave it to ripen

or rot.

Either’s good.

Says it better than prose although Cavafy doesn’t do too badly:

The most lively events do not inspire me at once. First, time must pass. Then later I remember them and am inspired.[37]

With me the immediate impression does not provide the impulse for work. The impression must become part of the past, must be falsified of itself, by time, without my having to falsify it.[38]

Even before Cavafy was an old man he was imagining being an old man looking back on his sexual escapades:

Very Seldom

He's an old man. Used up and bent,

crippled by time and indulgence,

he slowly walks along the narrow street.

But when he goes inside his house to hide

the shambles of his old age, his mind turns

to the share in youth that still belongs to him.

His verse is now recited by young men.

His visions come before their lively eyes.

Their healthy sensual minds,

their shapely taut bodies

stir to his perception of the beautiful.

[Edmund Keeley/Philip Sherrard]

Would it be too crass to say he gets off on regret? He wrote that when he was forty-one but he’d already written ‘An Old Man’ in 1894 when he was only thirty-one. What is it saying though that ‘The City’ and ‘The God Abandons Antony’ is not? When Giorgos Seferis said that Cavafy’s entire oeuvre effectively comprises a single poem, a “work in progress”,[39] he’s probably right and it underlines why he never sought to publish a definitive collection in his lifetime: he simply wasn’t done. In his introduction to the Oxford edition of Cavafy’s Collected Poems Peter Mackridge writes:

In most of Cavafy’s poems the speaker cannot be identified with the poet himself. These poems do not seem to present the poet’s own experiences, thoughts and feelings; they are like fictions that create, explore and experiment with alternative and parallel lives. In Cavafy’s poetic oeuvre there are no fewer than 251 named characters, 130 of them historical, sixty-four mythological, and fifty-seven fictional, in addition to a large number of anonymous figures.[40]

I get where he’s coming from but I’m not sure I agree. It’s not a matter of he’s wrong and I’m right but perhaps since I’ve spent the last few days completely embroiled in Cavafy’s world I find I see him in everything.

There is genuine ambivalence regarding his feelings about homosexuality. In a 1902 note he wrote:

I do not know if perversion empowers. I sometimes think so. But it is certain that it is a source of greatness.[41]

How to read that sentence? It sounds like a declamation but I’m not sure it is because of something E.M. Forster mentions in a letter to Cavafy:

Dear Cavaffy [sic]

Valassopoulo [an Egyptian lawyer who also translated Cavafy] was over this afternoon and told me that since I saw you something occurred that has made you very unhappy; that you believed the artist must be depraved; and that you were willing he should tell the above to your friends.[42]

All you have to do is look at his poems and the evidence is there:

In his poetry homosexual love is often described with the kind of vocabulary used by the society in which he lived: 'aberrant pleasure' ('A young man of letters...'), 'a love that's barren and deprecated' (‘Theatre of Sidon (A.D. 400)’)--the opposite of 'healthful love' ('In an old book').[43]

Often he uses “homoerotic code-words”,[44] as Peter Mackridge calls them; in modern parlance the equivalent expression would probably be ‘gay code’.

They looked with desire and affection at the statues –

but they talked to each other hesitantly,

with innuendos, with ambiguous words,

with phrases full of caution,

[from ‘The Bishop Pegasius’ translated Daniel Mendelshon]

“These are not intended to conceal,” Mackridge explains, “but rather to be understood by sensitive and sympathetic readers.”[45] That said “Cavafy was a virtuoso of both impression management and the fine arts of discretion.”[46]

It really is impossible to know deep down what Cavafy felt about himself. My suspicion is that, as I said earlier, he learned to live with himself but perhaps not like himself and there are plenty of examples of gay men over the years that fit that bill; Kenneth Williams, for one, jumps to mind. (Dr. Peter Jeffreys’ essay ‘Cavafian Catoptromancy’ provides some interesting thoughts on the subject as does Margaret Alexiou’s article ‘Eroticism and Poetry’.) Perhaps the most relevant piece of advice I took from Alexiou’s piece was a brief quote by Yangos Pieridis:

If you try to explain every poem autobiographically, it does not work: Cavafy used masks.[47]

As a poet myself I know full well that the ‘I’ in my poems is not always me or at least not all me or the real me. I should do Cavafy the same favour and not presume:

I am the 'I' beneath the text; I am both the question and the answer....[48]

One final poem from Cavafy:

Significance

The years of my youth, my life of pleasure –

how well I grasp their significance now.

Regrets are so unnecessary and pointless.

But at the time I couldn’t grasp their significance.

In the wanton ways of my youth

the course of my poetry was laid out,

the contours of my art were fashioned.

That’s why the regrets never took hold,

and any resolve toward restraint or change

lasted never more than a week or two, at best.

[Stratis Haviaras]

This has been a fascinating few days reading Cavafy’s poetry in various translations and also dipping into the many articles there are online about the man and his writing. As actual reviews goes I’ve really said very little about The Cavafy Variations apart from pulling ‘The City’ to pieces. That said I actually like what Parks has done but I still want to go away and try to have a crack at it myself; I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing and that’s probably what motivated Parks in the first place. The bottom line is that it’s an okay introduction to Cavafy. These are not necessarily the ten poems I would’ve picked but I’d hate to be asked to pick ten of my own poems that would provide readers with a representative cross-section of my work IF indeed that’s what Parks intended to do here. Maybe he just picked the ten poems he liked the best and that’s a perfectly valid selection method too.

[T]here are two schools of thought, with nuanced positions between. Loosely speaking, these may be dubbed ‘literalist’ and ‘Poundian’. A literal translation is one in which as nearly as possible, the English version should be an exact transfer from the original language; in contrast, the idea of Pound and others was (and is) that a translation first and foremost try to capture the ‘spirit’ of the original and transform it into poetry in English.[49]

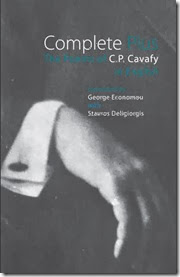

It does puzzle me why Cavafy didn’t provide his own English versions because, according to translator George Economou, although he doesn’t say where he’s quoting from, Cavafy only “tacitly tolerated” [50] the translations he saw of his work during his lifetime. Who knows? Robert Lowell called his own attempts at translation "Imitations". It puts the whole process into perspective. “Variations” is another good term.

![CavafyCVR2.indd CavafyCVR2.indd]() The Cavafy Variations is available from Rack Press for £5.00. As much as I enjoyed reading these and Parks does a decent job with his “variations”—although he does tend (wisely I think) to veer towards the Poundian—the frugal Scot in me would rather go for a used copy of his complete poems. At time of writing Dalven’s The Complete Poems of Cavafy was available for £5.24, Theoharis’s Before Time Could Change Them: The Complete Poems of Constantine P.Cavafy for £8.26, Haviaras’s The Canon: The Original One Hundred and Fifty-Four Poems for £9.83 and Sachperoglou’s C.P. Cavafy: The Collected Poems: with parallel Greek text for £6.86 although admittedly that’s for the ebook. Those with deeper pockets might be happy to fork out £15.52 for Mendelshon’s The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy. I couldn’t see a copy of Keeley and Sherrard’s Collected Poems on the UK site, which is odd because it’s only four years old, but as you can order it from the States for 1¢. I wouldn’t object to paying the extra postage. Of course all are available online in one form or another along with a goodly number of intelligent, thoughtful (and occasionally contradictory) essays on the man, a number of which I’ve listed below which are in addition to the texts cited from and listed in the references.

The Cavafy Variations is available from Rack Press for £5.00. As much as I enjoyed reading these and Parks does a decent job with his “variations”—although he does tend (wisely I think) to veer towards the Poundian—the frugal Scot in me would rather go for a used copy of his complete poems. At time of writing Dalven’s The Complete Poems of Cavafy was available for £5.24, Theoharis’s Before Time Could Change Them: The Complete Poems of Constantine P.Cavafy for £8.26, Haviaras’s The Canon: The Original One Hundred and Fifty-Four Poems for £9.83 and Sachperoglou’s C.P. Cavafy: The Collected Poems: with parallel Greek text for £6.86 although admittedly that’s for the ebook. Those with deeper pockets might be happy to fork out £15.52 for Mendelshon’s The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy. I couldn’t see a copy of Keeley and Sherrard’s Collected Poems on the UK site, which is odd because it’s only four years old, but as you can order it from the States for 1¢. I wouldn’t object to paying the extra postage. Of course all are available online in one form or another along with a goodly number of intelligent, thoughtful (and occasionally contradictory) essays on the man, a number of which I’ve listed below which are in addition to the texts cited from and listed in the references.

I’ll leave the last word to Maurice Leiter:

Had I Only

Lacking languages I stumble

in the darkness of translation

finding satisfaction second-hand

Here is Cavafy soft-spoken subtle

speaking free of affectation

or so it seems in this translation

said to be exemplary by many

But the curtain of my ignorance

keeps me from truly knowing him

nor is his work the sole example...

FURTHER READING

Yórgos Panayotídis, Constantine Cavafy – A biography without poetry

Chris Michaelides, Three Early Cavafy Items in The British Library

Kimon Friar, Cavafis and his Translators into English

Peter Bien, Cavafy's Three-Phase Development Into Detachment

Dimitris Dimiroulis, Cavafy's Imminent Threat: Still ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’

Lena Arampatzidou, Between the Barbarians and the Empire: Mapping Routes Toward the Nomadic Text

John P. Anton, The Special World of Cavafy's Poetry: from Symbol to Reality

Iraklis Pantopoulos, Two different faces of Cavafy in English: A corpus-assisted approach to translational stylistics

Helen Catsaouni, Cavafy and the Theatrical Representation of History

Anthony Dracopoulos, The Rhetoric of Dilemma and Cavafean Ambiguity

Davd Ricks, Cavafy and the Body of Christ

Daniel Mendelsohn, Cavafy and the Erotics of the Lost

George Kalogeris, The Sensuous Archaism of C.P. Cavafy

Cornelia A. Tsakiridou, Hellenism in C.P. Cavafy

Manuel Savidis, Cavafy Through the Looking-Glass

S. D. Kapsalis, "Privileged Moments": Cavafy's Autobiographical Inventions

Dimitris Papanikolaou, From the Darkrooms of Philology (an impassioned response to Savidis)

Robert Shannan Peckham, Cavafy and the Poetics of Space

Tilda Negri, The Metaphysics in C.P. Cavafy (click anywhere on the page to go to the index)

Latife Yazigi, Two Styles of Mental Functioning and Literary Language: A Phenomenological Psychological Reading of A. Machado and C. Cavafy

C.P. Cavafy Forum: links to various essays and articles

A booklet by the Embassy of Greece Press & Communication Office: lots of photos

C. P. Cavafy: The Typography of Desire: contains six essays including ‘Cavafy’s Greek (in Translation)’ by James Nikopoulos

Official website: a smorgasbord of all things Cavafy

REFERENCES

[1] Quoted in Daniel Mendelshon, The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy, p.1875

[2] Dan Chiasson, ‘Man with a Past', The New Yorker, 23 March 2009

[3]Ibid

[4] Quoted in Daniel Mendelshon, The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy, p.1884

[5] Quoted in Daniel Mendelshon, ‘As Good as Great Poetry Gets’, The New York Review of Books, 20 November 2008 and other places but I can’t find the original source

[6] Cavafy, toward the end of his life, insisted that “plenty of poets are poets only, but I am a historical poet.” Those last two words are one way of rendering what he said in Greek, which was piïtís istorikós; but the adjective istorikós can also be a substantive, “historian.” There is no way to prove it, but I suspect that what he meant was precisely what his work makes clear: that he was a “poet-historian.” – Daniel Mendelsohn, The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy, p.1900

[7] Quoted in Martin McKinsey, Hellenism and the Postcolonial Imagination: Yeats, Cavafy, Walcott, p.76

[8] J.A. Sareyannis, ‘What was most precious—his form’

[9]Ibid

[10] James D. Faubion, Cavafy/Cavafy: Toward the Principles of a Transcultural Sociology of Minor Literature, p.8

[11] J.A. Sareyannis, ‘What was most precious—his form’

[12] Quoted in Roderick Beaton, ‘The History Man’, Journal of Hellenic Diaspora, Special Double Issue: Spring-Summer 1983, p.31

[13] Quoted often, e.g. here, but I can’t find the original source

[14] Various terms get applied to these groupings. ‘Hedonic’ often replaces ‘sensual’ but apparently Cavafy treated ‘hedonic’ as a subcategory of the sensual (see Peter Mackridge, Introduction, Oxford World Classics: C.P. Cavafy: The Collected Poems)

[15] Daniel Mendelshon, The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy, p.1891

[16] J Phillipson, C.P. Cavafy Historical Poems, p.141

[17] Contemporary note left by Cavafy. Translated by Manuel Savidis and quoted in Daniel Mendelsohn, The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy, p.1891

[18] Note from 1906 quoted in Cornelia A. Tsakiridou, ‘The Photographic Dimension in Some Poems of C. P. Cavafy’, Journal of Hellenic Diaspora, September 1991, p.89

[19]Note from September 1902

[20] Quote from the Sengopoulos Notebook in Daniel Mendelshon, The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy

[21]Note from December 1906 translated by Manuel Savidis

[22] Edmund Keeley, ‘An Introduction’

[23]Ibid

[24] J.A. Sareyannis, ‘What was most precious—his form’

[25] Kōnstantinos Dēmaras, A History of Modern Greek Literature, pp.470, 471

[26] Quoted in Walter Kaiser, Review of C. P. Cavafy and elsewhere but I can’t find a reference to the original source

[27] Donald Davie quoted on the Waterloo Press archive page

[28] Quoted by several people but no link available to confirm

[29] C.P. Cavafy quoted in Edmund Keeley, Cavafy’s Alexandria, p.16

[30]Note from April 1907 translated by Manuel Savidis

[31] Quoted in Michael Haag, Alexandria: City of Memory, p.69

[32] Daniel Mendelshon, The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy, p.1881

[33] André Aciman, ‘The City, the Spirit, and the Letter: On Translating Cavafy’

[34] Peter Mackridge, Introduction, Oxford World Classics: C.P. Cavafy: The Collected Poems, p.xxiii

[35] Edmund Keeley, Cavafy’s Alexandria, p.6

[36]“In the poem’s final stanza, the narrator wonders whether even ancient Alexandria, famed for its louche and comely youths, could claim a young man as lovely as this down-at-the-heels boy. Here, the contrast between the allure of the youths in the glittering ancient city and that of a common blacksmith’s boy is suggestively conveyed by the shift in tone between the adjective used of the former, perikallis, and the noun used of the latter, agori: for the former is a high-flown katharevousa word taken directly from the Ancient Greek (which I translate by means of the rather stiff ‘beauteous’), while the latter is a noun as worn and plain as a pebble: ‘lad.’” – Daniel Mendelsohn, The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy, p.1900

[37] Undated fragment quoted in Roderick Beaton, ‘The History Man’, Journal of Hellenic Diaspora, Special Double Issue: Spring-Summer 1983, p.31

[38] Note from April 1929 quoted in Roderick Beaton, ‘The History Man’, Journal of Hellenic Diaspora, Special Double Issue: Spring-Summer 1983, p.32

[39] Giorgos Seferis, On the Greek Style, p.121

[40] Peter Mackridge, Introduction, Oxford World Classics: C.P. Cavafy: The Collected Poems, p.xv

[41]Note from December 1902

[42] Edward Morgan Forster ed., The Forster-Cavafy Letters: Friends at a Slight Angle, p.35

[43] Peter Mackridge, Introduction, Oxford World Classics: C.P. Cavafy: The Collected Poems, p.xx

[44]Ibid p.xxiii

[45]Ibid

[46] James D. Faubion, Cavafy/Cavafy: Toward the Principles of a Transcultural Sociology of Minor Literature, p.10

[47] Yangos Pieridis, Kavafis, p.27 quoted in Margaret Alexiou, ‘Erotocism and Poetry’, Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora, Special Double Issue: Spring-Summer 1983, p.64

[48] Presumably a quote by Cavafy. Alexiou ends her article with it but doesn’t provide any attribution and I’ve been unable to trace it elsewhere.

[49] Mike Doyle, ‘Cavafy’s Other Worlds’, Pacific Rim Review of Books

[50] Quoted in Randall Couch: Translating Cavafy: eros, memory, and art

A puppet show some time later reinforces the boy’s burgeoning beliefs. It was the story of Nichiren or Nisshin-shonin. In 1427—so about two hundred years before Iwajiro was born—Nisshin wrote a book, Rissho Chikokuron, and sent it to the shogunAshikaga Yoshinori. The book was critical of the Ashikaga regime and, as a result, Nisshin was arrested, imprisoned and horribly tortured for two years. One of the tortures was placing a hot pot on his head, and since then he was called Nabe kamuri Nisshin, meaning “Nisshin with pot on his head". He copes with the torture by chanting a sutra similar to the one Iwajiro had been practicing. On his way home the boy announces to his mother that he intends to leave home and become a monk like Nisshin. His mother does not object: “Yes, she said. Yes. When it’s time.”

A puppet show some time later reinforces the boy’s burgeoning beliefs. It was the story of Nichiren or Nisshin-shonin. In 1427—so about two hundred years before Iwajiro was born—Nisshin wrote a book, Rissho Chikokuron, and sent it to the shogunAshikaga Yoshinori. The book was critical of the Ashikaga regime and, as a result, Nisshin was arrested, imprisoned and horribly tortured for two years. One of the tortures was placing a hot pot on his head, and since then he was called Nabe kamuri Nisshin, meaning “Nisshin with pot on his head". He copes with the torture by chanting a sutra similar to the one Iwajiro had been practicing. On his way home the boy announces to his mother that he intends to leave home and become a monk like Nisshin. His mother does not object: “Yes, she said. Yes. When it’s time.”  Some people have no sense of smell. I have no sense of spirituality. You would think I would hate a book like this but I really didn’t. It was a story, a work of historical fiction. It was made up. Much of it is based on recorded fact but who knows what the man was really like, any more than we know what Jesus was like. The ‘story’ of the life of Jesus is a good read. You don’t have to believe any of it but as a story it works. And so does Spence’s presentation of the life of Hakuin. His struggle is not with some extant deity—that’s the thing about Buddhism, it’s as much a philosophy as a religion—but with himself. Most religions impel an individual to kowtow to the will of some higher being and although there are gods mentioned along the way in this book they don’t have the prominence one might expect mighty gods to have. The struggle here is with the self and even the most irreligious amongst us have that to struggle with on a daily basis. Here’s as good as example as any from the book:

Some people have no sense of smell. I have no sense of spirituality. You would think I would hate a book like this but I really didn’t. It was a story, a work of historical fiction. It was made up. Much of it is based on recorded fact but who knows what the man was really like, any more than we know what Jesus was like. The ‘story’ of the life of Jesus is a good read. You don’t have to believe any of it but as a story it works. And so does Spence’s presentation of the life of Hakuin. His struggle is not with some extant deity—that’s the thing about Buddhism, it’s as much a philosophy as a religion—but with himself. Most religions impel an individual to kowtow to the will of some higher being and although there are gods mentioned along the way in this book they don’t have the prominence one might expect mighty gods to have. The struggle here is with the self and even the most irreligious amongst us have that to struggle with on a daily basis. Here’s as good as example as any from the book:  Alan Spence is Professor in Creative Writing at the University of Aberdeen, where he is also artistic director of the annual WORD Festival. He was born in Glasgow in 1947, and much of his work is set in the city. He was recently commissioned by Scottish Opera for words for a libretto Zen Story, with music by Miriama Young. His first work was the collection of short stories Its Colours They Are Fine, published in 1977. This was followed by two plays, Sailmaker in 1982 and Space Invaders in 1983. The novel The Magic Flute appeared in 1990. In 1991 his play, Changed Days, was published before a brief hiatus. He returned in 1996 with Stone Garden, another collection of short stories. Since then he has published the novels Way To Go (1998) and The Pure Land (2006), a historical novel set in Japan based on the life of Thomas Blake Glover as immortalised in the story of Madame Butterfly.

Alan Spence is Professor in Creative Writing at the University of Aberdeen, where he is also artistic director of the annual WORD Festival. He was born in Glasgow in 1947, and much of his work is set in the city. He was recently commissioned by Scottish Opera for words for a libretto Zen Story, with music by Miriama Young. His first work was the collection of short stories Its Colours They Are Fine, published in 1977. This was followed by two plays, Sailmaker in 1982 and Space Invaders in 1983. The novel The Magic Flute appeared in 1990. In 1991 his play, Changed Days, was published before a brief hiatus. He returned in 1996 with Stone Garden, another collection of short stories. Since then he has published the novels Way To Go (1998) and The Pure Land (2006), a historical novel set in Japan based on the life of Thomas Blake Glover as immortalised in the story of Madame Butterfly.

Kirsty Gunn

Kirsty Gunn

Baron Frankenstein

Baron Frankenstein

Bibliotherapy

Bibliotherapy Ella Berthoud

Ella Berthoud

![Pythia Aegeus Themis Delphi[1] Pythia Aegeus Themis Delphi[1]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/-geVIjqAY5gU/Um5qGbd9DzI/AAAAAAAAHpE/N36M3x5anAk/Pythia%252520Aegeus%252520Themis%252520Delphi%25255B1%25255D_thumb.jpg?imgmax=800)