You mark my words, Georgie, total victory is in sight – Guy Fraser-Sampson, Au Reservoir

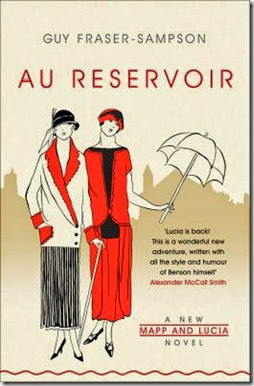

As the title suggests this is a goodbye novel. It’s Guy Fraser-Sampson’s third and final crack at recreating the world of Mapp and Lucia and he goes out in style. All of his three novels, Major Benjy, Lucia on Holidayand now Au Reservoir—au reservoir being the customary farewell proffered by residents of Tilling—are stylish affairs that relish verbal felicities in the same manner as Major Benjy would savour a chota peg of whisky or George Pillson might admire a white waistcoat with onyx buttons. This is a world where etiquette, decorum, good form, taste and propriety not only all still mean something but mean everything. The worst thing one can be seen to do is behave improperly. Or at least to get caught out behaving that way. Much impropriety takes place in this final battle of wills between Emmeline Pillson—affectionately known as Lucia (and, on occasions even more affectionately, as Lulu)—and her arch-rival Elizabeth Mapp-Flint. It is a battle royal that has raged across six novels by their creator, E.F. Benson, a further two by Tom Holt and now a final three by Fraser-Sampson. Mostly Lucia comes out on top but not always.

The events presented in these novels take place in an idealised and sanitised version of England, the kind of England you expect to find in books by Enid Blyton, Agatha Christie, P.G. Wodehouse and G.K. Chesterton. The characters are all larger than life at best veering at times towards out-and-out caricatures: the Vicar, for example, The Rev Kenneth Bartlett, is a kindly man always ready to jump to someone’s defence in the kind of Scottish accent they only speak in Brigadoon despite the fact he hails from Birmingham; the blusterous Major Benjy—Benjamin Mapp-Flint, Major Retd.—is exactly what you would expect from an old campaigner, a Miles Gloriosus whose life effectively stopped when he was demobbed and he now subsists on increasingly-fictional nostalgia, whiskies and soda and rounds of golf and then, of course, there’s Irene Coles, universally known as ‘Quaint’ Irene, a knickerbocker-clad lesbian, Germanophile and volatile socialist who paints naked women wrestlers, smokes a sailor’s pipe, and speaks her mind in a fruity bellow. I could go on but you get the idea. Any one of them could wander into a Jeeves and Wooster or a Father Brown and blend in parfectly (no, that wasn’t a typo).

Apparently there’s not in all England a town so blatantly picturesque as Tilling; it is the archetypal small English town. When Tillingites meet on the street the accepted and expected greeting is, “Any news?” but only news concerning Tilling or its inhabitants is considered real news; tittle-tattle is the only currency worth anything. For long and weary Mapp presided over this insular little world. That is until Lucia, who had been doyenne of the social scene of her home village of Riseholme, arrived and over the course of the novels gradually shifted the balance of power. By the time we get to Au Reservoir Lucia is now widely regarded as the richest woman in England (not sure if that includes royalty) and reigns supreme (if only in Tilling). But she’s getting on—even she recognises she’s getting on—and it’s time to start considering her legacy and not simply a museum celebrating all the famous mayors in Tilling’s proud history (which would, of course, feature her good self) and which she was considering in the last book. It would be so nice too, she muses, to leave this world as Dame Lucia. Mapp also realises that opportunities to bring Lucia to her knees are becoming thin on the ground and so decides it’s time to bring out the big guns. Somehow, however, in her enthusiasm she always manages to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

As with all these books what’s at stake is never anything on any real consequence. Mostly it’s the principle of the thing, e.g. can someone be banned from a bridge club before said club has been formed?

The crux of this particular novel revolves around a singular question: Does Lucia in fact know Noël Coward? Well, of course, she knows him—everyone in the country knows him—but does she know him know him? Well, no, she doesn’t but it’s not for want of trying. She has written to him—and also his friend John Gielgud—frequently; she is one of the country’s great letter writers but alas not one of its great reply receivers. Certainly not from the likes of Messrs Coward and Gielgud or indeed the various sovereigns and prime ministers who she’s seen fit to enter into unilateral correspondences with. Mapp, knowing full well that Lucia’s oft commented on friendship with Noël Coward is nothing but a fabrication of her imagination, is never averse to introducing the topic into conversation in the hope Lucia might trip herself up. We have an example of one their typical exchanges in the opening chapter of the book:

The crux of this particular novel revolves around a singular question: Does Lucia in fact know Noël Coward? Well, of course, she knows him—everyone in the country knows him—but does she know him know him? Well, no, she doesn’t but it’s not for want of trying. She has written to him—and also his friend John Gielgud—frequently; she is one of the country’s great letter writers but alas not one of its great reply receivers. Certainly not from the likes of Messrs Coward and Gielgud or indeed the various sovereigns and prime ministers who she’s seen fit to enter into unilateral correspondences with. Mapp, knowing full well that Lucia’s oft commented on friendship with Noël Coward is nothing but a fabrication of her imagination, is never averse to introducing the topic into conversation in the hope Lucia might trip herself up. We have an example of one their typical exchanges in the opening chapter of the book:

‘Perhaps Mr Georgie will be seeing that nice Noël Coward, as he is such a good friend of yours?’ [Mapp] enquired innocently. ‘Goodness, now I come to think of it what a pity that you’ve never invited him to stay at Mallards. Why, I can just imagine the two of you sitting there at the piano playing Mozartino duets.’

‘Dear Noël,’ Lucia said dreamily. ‘Such a great talent and yet what a lovely man – so unaffected, you know.’

‘Such a shame, then, dear one, that you haven’t been able to entice him down for the weekend,’ Mapp pushed on, sensing victory.

‘Yes, isn’t it?’ Lucia cried. ‘It would indeed be wonderful, as you say, Elizabeth, but sadly the poor man is so busy he hardly knows what day of the week it is most of the time. Why, he told me as much in his last letter.’

There came the hiss of a collective sharp intake of breath. The story of Noël Coward’s curt dismissal had of course been widely disseminated (Elizabeth had felt it no less than her duty, painful though it was to suggest that Lulu might not be entirely truthful).

‘His letter?’ Elizabeth echoed. ‘Was that the one in which he told you to leave him alone?’

Lucia gave one of her little silvery laughs.

‘Elizabeth, dear,’ she said, elongating the name playfully. ‘You really must learn to read other people’s letters more thoroughly.’

There was another group gasp.

‘Darling Noël is so temperamental that he has spats with all his friends on a regular basis. Why he wrote to me a few days later to apologise most charmingly and say that he was so taken up with writing his new play that he sometimes forgot to whom he was writing halfway through a letter. “But I just put it in the envelope, send it anyway and hope for the best,” he said. So like him, don’t you think?’

‘No idea, I’m sure, dear,’ Elizabeth said venomously. ‘After all, we don’t know him as well as you do, do we?’

How to force the issue? That is the problem and one Mapp has given a considerable amount of thought to. And then an opportunity arises: the upcoming fête at Tenterden. But before we get to that I should probably introduce Olga Bracely since  she’s to prove a key player in this little drama. Olga Bracely is in fact the stage and maiden name of Mrs Olga Shuttleworth a famous prima donna of the opera and an unusual friend of the Pillsons—of Lucia’s anyway—since, as Olga put it herself in Queen Lucia,she came out of an orphan school in Brixton but would much have preferred the gutter. Not quite common as muck but lacking some of the airs and graces one would expect considering the position she has risen to and although not quite the voice of reason she does occasionally put the posturings and pretences of her neighbours into perspective. Actually she’s more Georgie’s friend than Lucia’s although Lucia appreciates the fact that she’s a distraction that keeps her husband’s attentions away from her. In this respect Lucia’s relationship with Georgie is not dissimilar to Mapp’s with Major Benjy; the role of the husband in a marriage is probably one of the few things they do agree on:

she’s to prove a key player in this little drama. Olga Bracely is in fact the stage and maiden name of Mrs Olga Shuttleworth a famous prima donna of the opera and an unusual friend of the Pillsons—of Lucia’s anyway—since, as Olga put it herself in Queen Lucia,she came out of an orphan school in Brixton but would much have preferred the gutter. Not quite common as muck but lacking some of the airs and graces one would expect considering the position she has risen to and although not quite the voice of reason she does occasionally put the posturings and pretences of her neighbours into perspective. Actually she’s more Georgie’s friend than Lucia’s although Lucia appreciates the fact that she’s a distraction that keeps her husband’s attentions away from her. In this respect Lucia’s relationship with Georgie is not dissimilar to Mapp’s with Major Benjy; the role of the husband in a marriage is probably one of the few things they do agree on:

The possibility of physical infidelity worried [Lucia] not at all, for she was well aware that Georgie was as blissfully free from such tedious urges as had been Pepino [her first husband]; had she not been very sure of that fact, she would never have consented to marry him in the first place. More worrisome was that periodically, as Georgie was drawn back into Olga’s orbit, he would begin to exhibit troubling signs of gratuitous enjoyment of life, such as dancing to gramophone records, partying the night away

It may be true that Lucia has not, despite her best efforts, managed to become a familiar of Noël Coward but Olga is and it just so happens that while dining out in London with Georgie who should they run into if not Noël Coward but also John Gielgud? And to top things off photographic evidence appears the following day’s papers, a rather satisfying one on the society page of the Daily Telegraph— ‘Miss Olga Bracely, fresh from her triumph at the Royal Opera House, relaxes with Mr Noël Coward, Mr John Gielgud and Mr George Pillson’—and a slightly more salacious one in the Daily Mirror:

Covering half the front page was a photograph of Olga and Georgie locked in what appeared to be a passionate embrace in the bar at Sheekey’s. As he over-balanced on his stool, Georgie must have put out a hand for support and he now saw that it had come to rest, quite inadvertently, on what could only be described as Olga’s thigh.

Whatever way one looked at it the evidence certainly pointed to the fact that at least one of the Pillsons was known to Messrs Coward and Gielgud making their continued non-appearances harder to explain or excuse than ever. Mapp decides the time is ripe and phones Lucia:

‘Isn’t it wonderful that you and Noel Coward are such close friends?’ Mapp enthused. ‘You see, there’s the teensiest favour I’d like to ask you.’

Too late, Lucia smelt danger.

‘The Bartletts popped in a little while ago,’ Mapp purred, ‘asking for me to help with some fête thing over at Tenterden in three weeks’ time. Don’t know why really, after all everyone knows that sort of thing is much more in your line, dear worship. Why your tableaux vivants are the talk of East Sussex.’

‘I trust,’ Lucia broke in, ‘that you haven’t volunteered me for performing anything without consulting me first. Cattiva Elizabeth – you know how full my diary is. Anyway, I’m afraid it would be quite out of the question at such short notice. The preparations are extensive, dear, though of course I was forgetting – you’ve never actually featured in my tableaux, have you?’

Needless to say that’s not what’s being suggested:

‘And that’s when I had my little brainwave,’ Mapp said brightly. ‘I said to the Padre, “But why don’t you ask Lucia to invite her dear, dear friend Noël Coward down for the weekend and he can motor over to Tenterden with Cadman and open the fête?” And the Padre said, “What a bonny idea, Mistress Mapp,” and rang his friend the vicar at Tenterden, and he thought it was wonderful idea too. And then I positively clapped my little hands and thought how lovely it would all be.’

In Lucia’s mind, the gearwheels were spinning wildly but somehow she could not quite slip the clutch and engage them. What to say? What to do?

Well, the solution should be simple. Ask Olga to intercede. They try that but Noël’s having none of it. Is Mapp finally going to get one over on Lucia? Probably not. But even if she does there’s always the new bridge club to do battle over and if that fails Mapp’s got her Joker ready to play in the unassuming, bank-managerly shape of Mr Chesworth (who’s not a bank manager or connected in any way to a bank or any similar financial institution).

I’ve enjoyed all three of Guy’s novels but I think this one is possibly the best and who doesn’t want to go out on a high? The plot is carefully constructed with every i dotted and t crossed. Guy does has a tendency to tell rather than show—the whole shenanigans of the bridge tournament are relayed in a conversation following the event and the same with the fête although we do get to see a bit of the action first-hand (the farce concerning the coaches)—but Shakespeare got away with stuff like that all the time. As with Shakespeare the real pleasure is to be found here mainly in the verbal parrying but also in our being privy to the agonising thoughts that go on behind the masks, none more so than poor henpecked Major Benjy:

‘So what’s the answer?’ she enquired, staring at him intently.

The Major’s initial intention was to say, ‘Blowed if I know, old girl,’ and enquire what was for dinner, but he wisely refrained. He had an instinct that should he do so his wife might deploy a wide array of counter-attacking weaponry, ranging from accusations of gross insensitivity to foaming at the mouth and driving her knitting needles into his thigh. There was also of course the possibility that she might caustically enquire why it was, given that he’d been turning the matter over in his mind, that his prodigious intelligence had entirely failed to arrive at a helpful conclusion. Since his instinct on this occasion was to some extent sound, the recently strained marital relationship of the Mapp-Flints was happily not to be further tested that evening.

‘Why not just press ahead anyway?’ he ventured. ‘After all, we can’t get our deposit back, and we’ve got no other way of getting to Tenterden ourselves. Not unless you are planning to accept Lucia’s offer, and I can’t see you being inclined to do that.’

‘Oh, don’t be silly, Benjy,’ she said brusquely. ‘If we do that then everyone will simply say that we are copying Lucia.’

The Major noted silently that whenever his wife’s plans went awry they underwent a subtle but significant transformation from being ‘her’ plans to ‘their’ plans.

To add a level of finality to the book Guy appends a coda—actually Uno Piccolo Codettino—a Deadly Distant Finale in which we find out what Fate has in store for everyone; John Irving did the same in The World According to Garp. He literally kills off everyone (even Shakespeare never thought to try that) but as he pointed out in an e-mail to me, “I comfort myself with the thought that there are still huge gaps in the chronology should any subsequent books want to extend the series (which I very much hope they will).”

Before the coda Guy still has to wrap up his storyline and I have to say I was a little surprised with how he chose to end things. Yes, there is a clear winner. But as with his ending to Lucia on Holiday Guy introduces some pathos that leaves us thinking of these inventions as real people if only for a few pages. A fitting end to his innings then. Wonder who’ll be out to bat next?

***

Guy Fraser-Sampson originally qualified as a lawyer and became an equity partner in a City of London law firm at the age of 26, having already been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a member of the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, and a member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators. In 1986 he left the law and has since gained over twenty-five years’ experience in the investment arena, particularly in the fields of private equity funds, investment strategy and asset allocation.

Guy Fraser-Sampson originally qualified as a lawyer and became an equity partner in a City of London law firm at the age of 26, having already been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a member of the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, and a member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators. In 1986 he left the law and has since gained over twenty-five years’ experience in the investment arena, particularly in the fields of private equity funds, investment strategy and asset allocation.

Guy is well known as a provider of keynote addresses. He is also a prolific writer, supplying articles for every one of Europe's English language pension publications as well as numerous hedge fund and other investment titles, including his influential monthly column in Real Deals, which is read by the private equity community worldwide. He is also in regular demand for media interviews in various countries. In the UK, he has featured on both Sky and BBC television as well as Radio 4's Today programme. Links to some video interviews can be found here.

In addition to his Mapp and Lucia novels Guy also writes books on finance and investment and history. His first book on the Plantagenets (working title A Family at War) has been nominated for a Royal Society of Literature award. Cricket at the Crossroads: Colour, Class and Controversy 1967-1977 was published in September 2011. He also apparently writes detective fiction under a pseudonym which remains a closely guarded secret.