Yes. This really happened. – The Battle of Midway

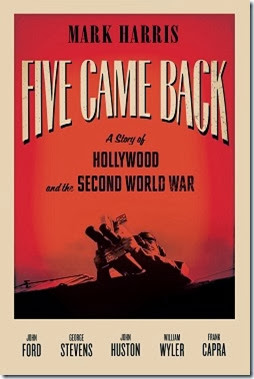

One thing I can say about Mark Harris with regard to his book Five Came Back—which is basically a study of how the American film industry was changed forever by World War II—is that he’s done his homework and I have little doubt that when he handed it in he got a gold star. This is a thoroughly-researched book that contains over sixty pages of end matter. It is easily readable and surprisingly entertaining. The man clearly did a lot of reading in researching his topic. And he’s managed to do what the five men highlighted in this book—John Ford, William Wyler, John Huston, George Stevens, and Frank Capra—all managed to do, take a huge amount of material from multiple sources and whittle it down to its essence. At 444 pages it’s still not a quick read (and I’m not including the end matter here) but, to be fair, he does cover a lot of ground.

The book begins in March 1938 and takes us through to February 1947, so we get a rounded picture of where Hollywood started out and where it ended up. In 1938 these five directors, four of whom were too old to be drafted and chose to enlist, were working on projects like Stagecoach(Ford), Gunga Din (Stevens) and You Can’t Take It With You(Capra). People were aware there was a war on but it was the European War. Nothing to do with them. They didn’t avoid mentioning the war in their films but they did so with care:

The stern eye of the Production Code as well as the studios’ collective fear of giving offense meant that controversial material was systematically weeded out of scripts before the cameras ever rolled. It also meant that even the most highly praised and successful studio directors were treated as star employees rather than artists entitled to shape their own creative visions.

[…]

The idea of pursuing a more socially or politically committed cinema, was … futile; no film with a strong political perspective would be able to surmount the studios’ fear of being labelled interventionists, or the antipathy of the censors…

What you have to remember is that most of the studios were owned by Jews and they were scared that people would accuse them of having an agenda but as things began to escalate in Germany some decided they simply couldn’t sit on the side-lines any longer and in 1939 Warner Bros produced the then controversial Confessions of a Nazi Spy. Its title alone was shocking and they fully expected the filmed to “be banned in many European countries (which it was) and might also face serious opposition from state and municipal censorship boards (which it did). But the studio stood by its conviction that the country was ready for the movie.” The problem was that “most studios maintained a strong financial interest in the German market and continued to do business with Hitler and his deputies.” Privately they may have held strong opinions but they were determined that “they would not allow their feelings, or anyone else’s, about what was happening in Germany to play out onscreen.” Stevens had it right when years later he said, talking to Leni Riefenstahl, “I think all film is propaganda.” Saying nothing is as bad as saying the wrong thing.

Everything changed in 1941 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. “Any trepidation the studios felt about making war movies vanished within weeks.” What also vanished was some of their best talent. The armed forces didn’t exactly open its arms to embrace Hollywood’s finest—“some … were astounded, and affronted that directors who had until recently been guiding Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers across a dance floor or teaching John Wayne to look heroic on a horse would now be entrusted with educating servicemen”—but the simple, undeniable fact was that even if these “[f]ilm-makers could not win the war … [they] had already shown that they could win the people.”

Naïve and inexperienced as they were—some couldn’t even salute properly—it was going to be a steep learning curve and take them away from their careers and families for far longer than any of them imagined. It would also change them permanently none more so that Stevens who was one of the first cameramen to film inside Nordhausen, a sub-camp of the concentration camp Dora-Mittelbau, which did little to prepare his for what he witnessed at Dachau. His work resulted in two films, The Nazi Planand Nazi Concentration and Prison Camps which were only intended for the eyes of those involved in the Nuremberg Trials.

The Nazi Plan

All the other film-makers were producing work to educate the soldiers but their eyes, even in wartime (much to my surprise), were on awards; some, admittedly, more than others.

The book has a long way to go before we get to this point and it lists chronologically the major documentary films produced throughout and just after the war and what was involved in their creation. Between them these five men were on the scene for almost every major moment of America’s war and in every branch of the service—army, navy and air force; Atlantic and Pacific; from Midway to North Africa, from Normandy to the fall of Paris and the liberation of the death camps. A lot of it involved bravery, some stupidity, way too much bureaucracy and more reconstruction and out-and-out fakery than I ever expected to read about. For example “[a]lthough [John Huston’s] San Pietro was presented to the movie going public as a wartime documentary, all the film’s combat scenes were staged.” The reasons for at least some staging becomes obvious especially once you’ve viewed one of the earliest films produced, John Ford’s The Battle of Midway, but this took things to a whole new level.

The Battle of Midway

Ford's footage of the Battle of Midway has an amateurish feel to it but Wikipedia’s wrong when it says the filming was impromptu; they knew they were going to be attacked and the director had stationed himself on the roof of the main island’s power station in readiness. “They were equipped with Eyemo and Bell & Howell 16-millimetre cameras and hundreds of feet of Kodachrome colour film.” At the end of the battle they’d amassed “four hours of silent film—about five hard-won minutes of which showed explicit combat”—but when Ford returned to Los Angeles he had a problem (and this is a problem that faced all the directors in this book): observe Navy (in his case) protocol or follow his instincts as a director. He chose to do the latter knowing full well that if he handed over his reels “the best shots would be indiscriminately parcelled out to newsreel companies by a War Department that was more eager to share visual evidence of an American triumph as quickly as possible than to wait for the movie that he believed could have exponentially greater impact.” On the surface that sounds commendable and in this instance everything worked out fine and he ended up winning an Oscar for the thing to boot but not every director’s films were as well received when handed in and cuts were commonplace. Ford hated the word ‘propaganda’ but semantics aside what he produced was the first propaganda film of the war and not his last. But the film was not without its issues:

Ford’s decision to keep the Japanese faceless and undefined in The Battle of Midway was less a matter of caution or sensitivity on his part than a reflection of the propaganda policy that by the summer of 1942 was hopelessly muddled and conflicted about what America’s enemy should look like on movie screens.

Who was the bad guy here? Hirohito? Since the general consensus was that he would remain in power after the end of hostilities some thought it would be “wiser to use General Tojo as the face of Japan’s lust for conquest.” Others wanted to point the finger at Japanese ideology. The danger, however, in castigating the common people was that it would cause problems for the thousands of Japanese Americans in the future who many already viewed as “a vast army of volunteer spies.” Internees were already being scattered across the country “to prevent them from clustering and conspiring.”

One of the projects that Frank Capra was asked to work on was series of films entitled Why We Fight. One of this series was entitled Know Your Enemy: Japan but it took years to get the film finished because of general ignorance about Japan and its motives, an unwillingness on the part of the U.S. government to determine what exactly the foreign policy towards Japan should be and disagreements between writers (he went through four sets) and director. Even as late as January 1945 the film had to undergo a series of final revisions to remedy an issue pointed out by the Pentagon: the film had “too much sympathy for the Jap people.” The film was released in its final form August 9th 1945, the day Nagasaki was bombed.

Know Your Enemy: Japan

This was a problem for everyone, not just Capra. The world of ad hoc documentary film-making was a far cry from what they were used to. Probably one of the biggest problems the directors faced was, perversely, a lack of direction. With the studios, like it or lump it, they knew what they were expected to produce and what they could reasonably get away with but the military didn’t really seem to know what to do with these guys. And so, feeling they had more scope than they’d been allowed before, they began imposing more of their personal visions on their work.

William Wyler’s probably best known in this context for his documentary Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress but the better film is one he produced after the war: The Best Years of Our Lives was the story of the homecoming of three veterans from World War II that dramatized the problems of returning veterans in their adjustment back to civilian life. It’s not a documentary but it drew heavily on Wyler's own experience returning home to his family after three years on the front. It ended up winning seven Oscars including best director. The film is especially noteworthy because of the casting of a non-actor, Harold Russell, to play the part of Homer Parrish who loses both hands; obviously finding a professional actor was going to be a problem.

Aircraft Graveyard scene from The Best Years of Our Lives

Many of the films produced over this period were ground-breaking both in technique and approach. A good example of the latter is another in Capra’s Why We Fight series, this one entitled The Negro Soldier. Up until this time coloured people in films were poorly represented, caricatures really and so when the film was first shown to the public no doubt they expected more of the same.

Richard Wright, whose novel Native Son had been published a few years earlier, attended the Harlem screening and told a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle that before the picture started, he had written down thirteen offensive stereotypes on the back of his program—Excessive Singing, Indolence and Crap Shooting among them— and intended to make a mark next to each one as it appeared onscreen. He didn’t check off a single box and told the reporter that he found the movie “a pleasant surprise.” Langston Hughes called the picture “distinctly and thrillingly worthwhile,” and New York’s black paper the Amsterdam News marvelled, “Who could have thought such a thing could be done so accurately … without sugar-coating and … jackass clowning?”

The Negro Soldier

Not all the films produced during this time were serious. There was also a place for humour as in the Private SNAFU cartoons created by Frank Capra, by far the most popular training films made for servicemen during the war.

[SNAFU – an acronym for ‘Situation Normal: All Fucked Up’ was] a grumbling, naïve, incompetent GI who would be featured in an ongoing run of short black-and-white cartoons in which—usually by catastrophically negative example that more than once ended with him being blown to bits—he would inform young enlistees about issues like the importance of keeping secrets and the need for mail censorship, as well as the hazards or malaria, venereal disease, laziness, gossip, booby traps, and poison gas.

Voiced by Mel Blanc and with early scripts by Theodor Geisel—‘Dr Seuss’ to you and I—it’s easy to see why they were popular.

Private SNAFU – ‘Spies’

As a historical document Harris’s book ticks all the boxes. His facts have obviously been checked and rechecked. But what’s especially good about his book is that it draws on the personal correspondence of the directors and reminiscences of those who knew them to flesh them out. Some wrote diaries, others letters. It’s a warts and all portrayal of the subject and his subjects; the egos, the drinking, the womanising, the award- and medal-chasing, the revisionism (Ford was especially guilty of misremembering the past), the stresses, the strains, the losses. These were very human men. And they made very human films. The films aren’t perfect either but they did make a difference. I enjoyed the honesty of this book. It opened my eyes.

***

Mark Harris graduated from Yale University in 1985 with a degree in English. In 1989, he joined the staff of Entertainment Weekly, a magazine published by Time Inc. covering movies, television, music, video and books. Mark worked on the staff of the magazine, first as a writer and eventually as the editor overseeing all movie coverage, from its launch in early 1990 until 2006. He now writes a column for the magazine called The Final Cut. In 2008, Harris published Scenes at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood, an examination of how the American film industry changed with the 1960s. Harris is married to the playwright Tony Kushner.

Mark Harris graduated from Yale University in 1985 with a degree in English. In 1989, he joined the staff of Entertainment Weekly, a magazine published by Time Inc. covering movies, television, music, video and books. Mark worked on the staff of the magazine, first as a writer and eventually as the editor overseeing all movie coverage, from its launch in early 1990 until 2006. He now writes a column for the magazine called The Final Cut. In 2008, Harris published Scenes at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood, an examination of how the American film industry changed with the 1960s. Harris is married to the playwright Tony Kushner.