Writing is a private thing. It's boring to watch, and its pleasures tend to be most intense for the person who's actually doing the writing. - Audrey Niffenegger

Etymology is a fascinating subject. Whenever I look up a new word I virtually always have a glance at where the word originated. Take ‘privacy’ for example. My Dad grew privet hedges in his front and back garden and all my life I assumed that they were there to ensure the family’s privacy and that there must be a correlation between the words ‘privet’ and ‘private’.

Privacy (from Latin: privatus"separated from the rest, deprived of something, esp. office, participation in the government", from privo"to deprive").

‘Private’ occupies twelve columns of the Oxford English Dictionary, not counting its various relatives so the above you will appreciate is a very, very limited definition.

The term ‘privet’ tends to be used these days for all members of the genus Ligustrum—my father’s hedge was a ligustrum japonicum, for example—however, according to Wikipedia, some forensic ligua-horticuluralists posit that the common name for privet actually originates from the Russian for ‘hello’ (Привет) since the plant is often found to the side of unpaved roads. That said there is a Latin connection, too, since the generic name was applied by Pliny the Elder to Ligustrum vulgare and that was a while ago. The bottom line is that no one knows anymore why privets are called privets.

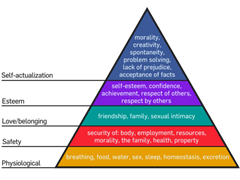

I find it interesting that the word ‘privacy’ derives from a word that means ‘to deprive’ because I’ve always considered deprivation as an undesirable thing. As long as anyone has their basic needs satisfied—and by that I don’t just mean starvation rations—they are warm, protected from the elements, have company and a place to sleep—we all know Maslow’s chart—you couldn't really say that they were being deprived. They might have been used to living in the lap of luxury but what they have become used to and what they need to be comfortable are two different things.

I value my privacy. The implication is that my insisting on it is detrimental in some way to others. I am depriving them of me but let’s face it if you had no me in your lives—let’s say I dropped dead tomorrow—you wouldn’t waste away for the lack of me. My wife, the one person on this earth who is privy to just about everything I do, might (I hope) go through a bit of a rough patch but she’s a tough old bird and she’d pull through; life toddles on. Although we live in each other’s pockets, Carrie and I both recognise the other’s need for privacy.

In actuality the Greeks viewed it a little differently:

Hannah Arendt… in her book The Human Condition has suggested that what we take to be the private realm was thought of in classical Greek times to be the realm of “privation” or deprivation—a realm in which persons saw to their material dependencies, like sustenance, and not to their creative and rational, or specific human aspects [which] could emerge only in political activities performed in the public realm.[1]

No one would bat an eye being seen eating publicly now although a few of us might be embarrassed if our efforts at food preparation were televised for all to see. I’m reminded of a science fiction short story about the problems faced in a first contact situation because the alien race is revolted by the fact the humans insist on eating as a group and are equally puzzled when the humans object when they start copulating in front of them.

It’s odd when you look at Maslow's hierarchy of needs—friendship, family and sexual relations are all there on Level III but nowhere do I see privacy mentioned. The fact is his chart is an over-simplification of what people need. Maslow himself identified the following 15 characteristics of a self-actualised person (self-actualisation is the highest Level):

- They perceive reality efficiently and can tolerate uncertainty;

- Accept themselves and others for what they are;

- Spontaneous in thought and action;

- Problem-centred (not self-centred);

- Unusual sense of humour;

- Able to look at life objectively;

- Highly creative;

- Resistant to enculturation, but not purposely unconventional;

- Concerned for the welfare of humanity;

- Capable of deep appreciation of basic life-experience;

- Establish deep satisfying interpersonal relationships with a few people;

- Peak experiences;

- Need for privacy;

- Democratic attitudes;

- Strong moral/ethical standards.

Needless to say there has been much debate about which items should and should not be on this list. You don’t need to tick all fifteen boxes to be self-actualised for starters. Self-actualisation is a matter of degree. As Maslow himself said: “There are no perfect human beings.”[2]

Needless to say there has been much debate about which items should and should not be on this list. You don’t need to tick all fifteen boxes to be self-actualised for starters. Self-actualisation is a matter of degree. As Maslow himself said: “There are no perfect human beings.”[2]I tend to think of myself as a very private person. I think a great many writers would say that. Is being a private person the same as being a solitudinous person though? I don’t think it necessarily has to be. It can but it’s not compulsory. I’m actually not that crazy about being on my own for too long. I like it that my wife sits a few feet away from me. She does her thing and I do mine and rarely, if ever, do either of us ask what the other is doing. If one of us cares to share what we’re reading or working on that’s another matter and we do occasionally. But mostly we sit here, listen to music and do what we have to do. When I have work for her to read or edit I attach it to an e-mail and send it off to her usually mentioning (because I don’t trust e-mails) that I’ve sent her something and to look out for it. The exception is poetry. I generally pass her a printed sheet with a poem on it and stand there expectantly.

I see a lot of writers online who seem to find sharing beneficial or even if they don’t find it especially beneficial they see it as the norm to tell people what they’re working on and how many words they’ve written that day. They update their Facebook profiles and a few of their friends leave encouraging remarks or click ‘like’. This, of course, is especially evident when it’s NaNoWriMo month when it’s all people talk about which makes my life easy because I just don’t read any of their blog posts for a month. It’s not that I’m not interested… No, I’m lying, I’m not interested. I don’t see that my interest should be a consideration. No one needs me to be interested in their writing. Wouldn’t it be horrible if no one wrote any books because their friends weren’t interested? Actually I think that might not be a bad thing. There are a lot of books written during the month of November that really should never have seen the light of day. I’m not anti-NaNoWriMo. It’s just not for me. I’m not that kind of writer. I understand that jobbing writers have to be able to sit down and write come hail, rain or shine and all credit to them but, with the exception of this blog (which shows I’m perfectly capable of churning out decent writing on a regular basis over an extended period of time), that’s not me.

Writing, for me, is a private thing. I’m not interested in sharing it with others. I’m happy to share my written words with others, the product of my writing, but the writing process is all mine. And it’s private. There was a documentary on SkyArts on May 22nd called Close Up – Photographer at Work and one of the photographers featured was Jay Maisel who had this to say about his art:

The product is a by-product; the act of seeing is the moment of fun.

Fun is not a word that I use very often. I have fun—Origin:1675–85; dialectal variant of obsolete fon to befool—but for some reason it’s not a word that I leap to use to describe the things that give me pleasure. I’m not saying that writing’s not ‘fun’—and, yes, of course, sometimes it’s anything but fun—but even when it’s not fun there is a kind of pleasure that can be derived from wrestling with words. I’m having ‘fun’ now. I don’t look as if I am but, trust me, I am. But it’s a selfish kind of fun. And it’s not for sharing.

I’m not big on process. My wife is. I showed here a photo yesterday and her first question —not unreasonably—was: “Was that Photoshopped?” It probably was. I, personally, didn’t care. It was a cool image and I really didn’t much care to what lengths the photographer went to achieve the result; only the end result mattered. And I suspect most people are the same when it comes to what they read; they really don’t care how long it took an author to produce said work of fiction, how many mugs of coffee they drank, shots of whisky they threw back, tears they shed or reams of paper they screwed up and tossed at a wastepaper bin that really would have worked much better if it was sitting next to their desk and not on the other side of the damn room. All our readers are interested in is the final product once it has been edited, proofread and printed in a format that’s to their liking. I, likewise, don’t much care where they read my books, be they on trains, toilets, in baths, beds, cars (hopefully not driving), or sprawled across sofas listening to Brian Eno. That’s their business and it’s private.

I don’t believe that telling people what I’m doing will jinx the project. I don’t have time for anything like that. A book, for me at least, is a fluid thing and most of the time what I’m working with or thinking about is a mess and, to be honest, I’m a little embarrassed about how much of a mess. Once it’s been tidied up I’m perfectly happy to let you wander round but as I know you’re going to judge me—and don’t pretend for one second that you won’t because we all do—I only want to be seen at my best.

You talk about men and women practicing law. No one ever talks about people practicing writing and yet that’s what we do with every sentence. Yes, I know, we put into practice the things we’ve learned about grammar and spelling and sentence construction and all that malarkey but that’s not what I mean. I mean we practice writing a sentence. We write a sentence, read it back, fiddle with it, reread it, tweak it a bit more, decide it’ll do, move onto the next one and then see how it looks a few minutes/hours/days later when you come to edit the paragraph in which it finds itself. I don’t really want to share the sentences I’ve got wrong. I want people to imagine that I wrote the book from beginning to end without changing a word.

That doesn’t mean I’m not willing to talk about the writing process after the event for the sake of sharing my experiences with fellow writers to help them realise that the hell they’re going through for the sake of their writing isn’t all that unusual, and none of us, not one us, rattles off books like they do on the telly. I consider it is a duty incumbent on all authors to divulge our practices, to let newbies peek behind the curtain but that’s, as I said, after the event. If I can remember, because they tell me that mothers don’t usually remember much about the experience of childbirth—just a general awareness that it was painful and drawn out—and I think writing’s like that, too, which is why, a wee while after finishing one book, we find ourselves fooling around with a new one. I ‘remember’—and ‘remember’ is in inverted commas for a reason—I ‘remember’ going through bouts of absolute despair writing certainly the last three books and regretting bitterly not quitting at two but, you see, I don’t remember the despair just that there was despair. I knew (or at least I believed) that, like depression, it would lift but whilst in the midst of it I just wanted to be left alone to endure it.

Apparently the Japanese have no word for ‘privacy’. They don’t get it as a concept. I find that odd because, if you’d asked me, I would have said that, as a nation, the Japanese would be amongst the most private in the world. Decorum, honour, things being done properly all smack of a nation of buttoned-up people not that dissimilar from the reserved, stiff-upper-lipped British. The Swedes have a close equivalent for ‘private’ (privat) but nothing for ‘privacy’. Google Translate says it’s ‘integritet’ which it translates back as ‘integrity’. I suppose I can see the connection.

The problem with privacy is that it’s often interpreted as secrecy: Wot’s ‘e ‘idin’? Secrets are not automatically bad or horrible things although there is an assumption that they are; guilt is assumed; people don’t have secrets, they have guilty secrets. If we’re not opening up, sharing with the group and providing full disclosure then we’re at it; we’re on the fiddle. I’ll be honest, most of the times when I’ve badgered—yes, badgered—others into fessing up this or that I’ve usually been pretty underwhelmed by their confessions; most of us live unexciting lives and yet we all have things we want to hide. Generally these are things that if they get out we feel they’ll embarrass us or cause people see us in a less than favourable light. It doesn’t seem to matter that others will have a similar assortments of faux pas that they’d rather keep to themselves. We fear a loss of dignity which is another one of those words we all use and yet struggle to define. Which brings us round to another word: entitlement, a guarantee of access to benefits based on established rights or by legislation.

Although there are those who might like to suggest otherwise—e.g. Mark Zuckerberg—people’s need for privacy is not dead, not dying, not even poorly. We share differently to the ways we used to but people have always shared or withheld sharing if they don’t see the need for or the benefit of sharing. Most of the things I share on Facebook I do to keep up the impression that I’m sharing, that I’m playing the game, being a good sport, joining in. Occasionally—very, very occasionally—I do come across something that I really want to pass on—my post on my experiences with aspartame is a good example—but they’re few and far between.

Although there are those who might like to suggest otherwise—e.g. Mark Zuckerberg—people’s need for privacy is not dead, not dying, not even poorly. We share differently to the ways we used to but people have always shared or withheld sharing if they don’t see the need for or the benefit of sharing. Most of the things I share on Facebook I do to keep up the impression that I’m sharing, that I’m playing the game, being a good sport, joining in. Occasionally—very, very occasionally—I do come across something that I really want to pass on—my post on my experiences with aspartame is a good example—but they’re few and far between. When you get a new job you sign a contract which sets out what your boss’s expectations are and what your entitlements are. A marriage certificate is generally much briefer and so the entitlements are a bit vaguer. But what about friends? There will be a number of people reading this who are my friends. What does that entitle you to? Zuckerberg makes the mistake of assuming that all friends are equal but that’s not the case. I personally think the term ‘efriend’ should be used more. But even there I have efriends who I only communicate with via Facebook, those who I exchange comments with on our respective blogs, those who I email and those (okay just the one so far) who I talk to on the phone and all of these are modes of electronic communication. For the most part I still guard my privacy.

In Part Two, a brief history of privacy.

Further Reading

- James Rachels, Why Privacy is Important

- Michael Boyle, A Shared Vocabulary for Privacy

- Valerie Steeves, Reclaiming the Social Value of Privacy

- Bonnie S. McDougall, Concepts of Privacy in English

- Alexander Rosenberg, Privacy as a Matter of Taste and Right

- Leysia Palen and Paul Dourish, Unpacking “Privacy” for a Networked World

- Knowing more about privacy makes users share less with Facebook and Google– A SimplicityLabTM Consumer Research Survey

- There are also a whole host of short articles relating to the legal definition of privacy here.

References

[1] Ferdinand Schoeman, ‘Privacy: philosophical dimension of the literature’ in F. Schoeman ed. Philosophical Dimensions of Privacy: An Anthology, p.10

[2] A H Maslow, Motivation and Personality, p.176