The limited circle is pure. – Franz Kafka

My name is Jim and I’m an introvert. If there was such an organisation as Introverts Anonymous I’d have no problems standing up in front of the group and making that claim. I’ve sat the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator assessment many times and although the last three of the four dichotomies vary—sometimes I’m more Sensing than Intuition, sometimes I’m more Thinking than Feeling—the first one never changes. I am an introvert. Only now I’m not so sure. But is that a bad thing? Feeling isn’t better or worse than thinking; they complement each other.

There are a number of sites and articles online called ‘Introverts Anonymous’. Ric Sanchez wrote one here where he introduces himself as follows:

Hi, my name is Ric, and I’m a recovering introvert. I’m here to help my fellow socially-anxious.

I’m sure Ric’s a decent guy and I can see why he might equate introversion with illness because we live in a world where extroversion is presented as the norm but I don’t feel sick and subsequently have no desire to get better. There is a site called I Am an Introvert which exists to provide advice and support to introverts and I get why it exists just as I get why there are sites that offer support for blacks, gays and women all of which are perfectly normal things to be. There are also support sites for addicts, phobics and people with personality disorders, things which most of us wouldn’t want to be. Which list should we put ‘introvert’ in?

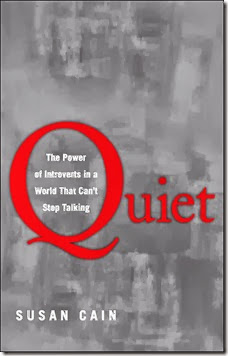

A friend of mine recently tweeted that she’d read Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking by Susan Cain and so I thought I’d take a look-see. I even set aside the book I’d just started to read it right away while I was in the mood. I expected to come away from the book feeling more comfortable with my introversion but, oddly enough, that’s not what happened and I’m not sure why. So I thought I’d write about it and see if I could work it out on the page which is what I do.

From the book’s introduction:

It makes sense that so many introverts hide even from themselves. We live with a value system that I call the Extrovert Ideal—the omnipresent belief that the ideal self is gregarious, alpha, and comfortable in the spotlight. The archetypal extrovert prefers action to contemplation, risk-taking to heed-taking, certainty to doubt. He favours quick decisions, even at the risk of being wrong. She works well in teams and socializes in groups. We like to think that we value individuality, but all too often we admire one type of individual—the kind who’s comfortable “putting himself out there.” Sure, we allow technologically gifted loners who launch companies in garages to have any personality they please, but they are the exceptions, not the rule, and our tolerance extends mainly to those who get fabulously wealthy or hold the promise of doing so.

Introversion—along with its cousins sensitivity, seriousness, and shyness—is now a second-class personality trait, somewhere between a disappointment and a pathology. Introverts living under the Extrovert Ideal are like women in a man’s world, discounted because of a trait that goes to the core of who they are. Extroversion is an enormously appealing personality style, but we’ve turned it into an oppressive standard to which most of us feel we must conform.

But what exactly is an introvert? ‘Introversion’ is one of those terms coined by psychologists that have made their way into the everyday speech of millions of people. Someone might say, “I’m a bit OCD,” and we all think we know what they mean but saying, “I’m a bit OCD,” or, “I’m a tad introverted,” is like saying, “I’ve had a touch of the flu.” Influenza is real—you can look at influenza virions under a microscope and although there are different strains, influenza is still a physical thing—whereas introversion is a manmade term, a way of classifying humans and people have been divvying up humanity for centuries: rich versus poor, free versus enslaved, believers versus nonbelievers, black versus white, left versus right. It’s in our genes to need there to be an us and a them, a normal and an abnormal. And, of course, there are people who are abnormal but let’s not get confused: different is not the same as abnormal.

No one can agree on how to define introversion. Cain writes:

[T]here is no all-purpose definition of introversion or extroversion; these are not unitary categories, like “curly-haired” or “sixteen-year-old,” in which everyone can agree on who qualifies for inclusion. For example, adherents of the Big Five school of personality psychology (which argues that human personality can be boiled down to five primary traits) define introversion not in terms of a rich inner life but as a lack of qualities such as assertiveness and sociability. There are almost as many definitions of introvert and extrovert as there are personality psychologists, who spend a great deal of time arguing over which meaning is most accurate. Some think that Jung’s ideas are outdated; others swear that he’s the only one who got it right.

As she says there are a number of personality tests based on introversion versus extroversion: Jung’s Typology, Big Five, Myers Briggs, Socionics, Enneagram. Cain takes a broad-brush approach in how she defines it, almost a layman’s definition and (wisely, I think) doesn’t get bogged down in irrelevant minutiae; this is a book for the man in the street.

When I said at the start of this article that I was an introvert you all knew what I meant. And that’s fine. This is a popular science book—an interpretation of science intended for a general audience—and so as not to lose her audience in technobabble she resorts to anecdotes, many of which are personal, to make her point. And she makes it well. She begins with two historical figures most people—certainly most Americans—will know very well: Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. This is a good way to illustrate how an introvert and an extrovert can work together to change the world but there are far more examples of what happens when extroverts fail to listen to introverts, indeed she actually suggests that the recent financial crisis could’ve been avoided had the extroverts not been in charge:

When I said at the start of this article that I was an introvert you all knew what I meant. And that’s fine. This is a popular science book—an interpretation of science intended for a general audience—and so as not to lose her audience in technobabble she resorts to anecdotes, many of which are personal, to make her point. And she makes it well. She begins with two historical figures most people—certainly most Americans—will know very well: Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. This is a good way to illustrate how an introvert and an extrovert can work together to change the world but there are far more examples of what happens when extroverts fail to listen to introverts, indeed she actually suggests that the recent financial crisis could’ve been avoided had the extroverts not been in charge:

When the credit crisis threatened the viability of some of Wall Street’s biggest banks in 2007, Kaminski saw the same thing happening [as happened when he worked for Enron]. “Let’s just say that all the demons of Enron have not been exorcised,” he told the Post in November of that year. The problem, he explained, was not only that many had failed to understand the risks the banks were taking. It was also that those who did understand were consistently ignored—in part because they had the wrong personality style: “Many times I have been sitting across the table from an energy trader and I would say, ‘Your portfolio will implode if this specific situation happens.’ And the trader would start yelling at me and telling me I’m an idiot, that such a situation would never happen. The problem is that, on one side, you have a rainmaker who is making lots of money for the company and is treated like a superstar, and on the other side you have an introverted nerd. So who do you think wins?”

If introverts get lionised a bit in this book then the extroverts could complain they get caricatured. And she does talk a lot about extroverts, too much for my tastes. But there one group she doesn’t talk about much at all: the ambiverts. I sat this test and this was the result:

You're an ambivert. That means you're neither strongly introverted nor strongly extraverted. Recent research by Adam Grant of the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Management has found that ambiverts make the best salespeople. Ambiverts tend to be adept at the quality of attunement. They know when to push and when to hold back, when to speak up and when to shut up. So don't fall for the myth of the extraverted sales star. Just keep being your ambiverted self.

I was cynical enough to imagine that the test is skewed so that everyone who sits it came out as an ambivert so I filled in answers that I knew would define me as an extrovert and they did. This test gave me a score of 38 which ranks me as “an introvert with some ambivert functions”; two more points and I would’ve been a fully-fledged ambivert.

I’ve sat tests before to see if I was left-brained or right and usually the answers indicated that I was pretty much evenly balanced which is why I guess in the Myers-Briggs test I swing back and forth on most of the dichotomies. It was one of the stories in the book that made me start to think about this insistence towards polarisation. It was the story of Maya and Samantha. Here’s the setup:

It’s a Tuesday morning in October, and the fifth-grade class at a public school in New York City is settling down for a lesson on the three branches of American government. The kids sit cross-legged on a rug in a brightly lit corner of the room while their teacher, perched on a chair with a textbook in her lap, takes a few minutes to explain the basic concepts. Then it’s time for a group activity applying the lesson.

She divides the class into three groups of seven kids each: a legislative group, tasked with enacting a law to regulate lunchtime behaviour; an executive group, which must decide how to enforce the law; and a judicial branch, which has to come up with a system for adjudicating messy eaters.

[…]

In Maya’s group, the “executive branch,” everyone is talking at once. Maya hangs back. Samantha, tall and plump in a purple T-shirt, takes charge. She pulls a sandwich bag from her knapsack and announces, “Whoever’s holding the plastic bag gets to talk!” The students pass around the bag, each contributing a thought in turn. They remind me of the kids in The Lord of the Flies civic-mindedly passing around their conch shell, at least until all hell breaks loose.

Maya looks overwhelmed when the bag makes its way to her.

“I agree,” she says, handing it like a hot potato to the next person.

The bag circles the table several times. Each time Maya passes it to her neighbour, saying nothing.

The thing that got me about this was, in a similar situation, I would’ve been Samantha. At school I was invariably the kid who ended up taking charge of groups—admittedly because no one else usually wanted to—but I never found it a problem and I had no trouble expressing my thoughts and even convincing the group to do things my way. Not your classic introvert then. To round Maya out Cain tells us a bit more about her:

Maya … loves to go home every day after school and read. But she also loves softball, with all of its social and performance pressures. She still recalls the day she made the team after participating in tryouts. Maya was scared stiff, but she also felt strong—capable of hitting the ball with a good, powerful whack. “I guess all those drills finally paid off,” she reflected later. “I just kept smiling. I was so excited and proud—and that feeling never went away.”

I was in the rugby team at secondary school. I was never “scared stiff” to join but it did suit me to play right-wing where I got to excel at running—that is why I was on the team—rather than tackling which I was no good at. Despite my size I always hated physical conflict and in the few fights I got in I simply stopped others injuring me rather than set out to hurt them. The coach was astute enough to realise where my talents lay and used me accordingly.

The thing is when I look at the list in Cain’s book:

…reflective, cerebral, bookish, unassuming, sensitive, thoughtful, serious, contemplative, subtle, introspective, inner-directed, gentle, calm, modest, solitude-seeking, shy, risk-averse, thin-skinned.

which she describes as a “constellation of attributes” I see me. The last thing I am is:

…ebullient, expansive, sociable, gregarious, excitable, dominant, assertive, active, risk-taking, thick-skinned, outer-directed, light-hearted, bold, and comfortable in the spotlight.

When I know what I’m talking about I am confident and I’m usually more intelligent than the people I’m surrounded by so much so that they’re not usually hard to intimidate should the mood take my fancy (which, to my shame, it has done) but I’m certainly no “man of action” and am even less so the older I get and the more opportunity I get to indulge those qualities that define introverts.

Cain does talk quite a bit about a third class however: the pseudo-introvert. Is that maybe what I am, an introvert who’s good at putting on a front? Well I can’t pretend I’ve never found myself out of my depth and had to fake it. When I was an IT trainer I spend the vast majority of my time working with small groups or individuals but later when I was asked to design a call centre course I had to include short lectures which I did not enjoy. I’ve never had problems addressing a group and have done on many occasions as long as I was prepared. I find speaking extemporaneously difficult. I do exactly the same it seems as Gandhi:

Cain does talk quite a bit about a third class however: the pseudo-introvert. Is that maybe what I am, an introvert who’s good at putting on a front? Well I can’t pretend I’ve never found myself out of my depth and had to fake it. When I was an IT trainer I spend the vast majority of my time working with small groups or individuals but later when I was asked to design a call centre course I had to include short lectures which I did not enjoy. I’ve never had problems addressing a group and have done on many occasions as long as I was prepared. I find speaking extemporaneously difficult. I do exactly the same it seems as Gandhi:

When a political struggle occurred on the committee, Gandhi had firm opinions, but was too scared to voice them. He wrote his thoughts down, intending to read them aloud at a meeting. But in the end he was too cowed even to do that.

Gandhi learned over time to manage his shyness, but he never really overcame it. He couldn’t speak extemporaneously; he avoided making speeches whenever possible. Even in his later years, he wrote, “I do not think I could or would even be inclined to keep a meeting of friends engaged in talk.”

That said I’m not, and never have been, shy and it’s a misnomer to think of introverted people as shy; I don’t hate people but I prefer them in small doses (you will always find me in the kitchen at parties). But getting back to oration, I don’t love public speaking but if I’m well prepared, have rehearsed enough and have a glass of water to hand then I can cope. I don’t get off the podium dripping with sweat and I’ve never thrown up before, after or during a talk. But I’m not a naturally-gifted speaker. Cain devotes an entire chapter of her book to public speaking. In it she talks about our ability to stretch our personalities:

We might call this the “rubber band theory” of personality. We are like rubber bands at rest. We are elastic and can stretch ourselves, but only so much.

Preconceptions encourage prejudgement. Oh, you’re an introvert so you won’t be able to do x, y or z. Who says? Cain’s book is full of examples of coping mechanisms, helping introverts blend in (and even excel) in a world full of extroverts. Part of her solution to the problem is for introverts to recognise the effects stretching their personalities can have on them. A spring or a rubber band will return to its original shape unless too great a force is applied to it over too long a time. So too with people. Cain gives numerous examples of adaptive strategies. Greg wants weekly dinner parties at his home and with his wife present as hostess; Emily wants none. The solution?

Instead of focusing on the number of dinner parties they’d give, they started talking about the format of the parties. Instead of seating everyone around a big table, which would require the kind of all-hands conversational multitasking Emily dislikes so much, why not serve dinner buffet style, with people eating in small, casual conversational groupings on the sofas and floor pillows? This would allow Greg to gravitate to his usual spot at the centre of the room and Emily to hers on the outskirts, where she could have the kind of intimate, one-on-one conversations she enjoys.

This issue solved, the couple was now free to address the thornier question of how many parties to give. After some back-and-forth, they agreed on two evenings a month—twenty-four dinners a year—instead of fifty-two. Emily still doesn’t look forward to these events. But she sometimes enjoys them in spite of herself. And Greg gets to host the evenings he enjoys so much, to hold on to his identity, and to be with the person he most adores—all at the same time.

Compromise is often hard but it seems like extroverts have a harder time with it than introverts because they often either refuse to listen or don’t listen properly. It’s a sweeping statement and probably less true in the home than it is in the worlds of politics and business.

Of course Cain’s not the first person to tackle this subject. Jonathan Rauch wrote an entertaining article for The Atlantic—one called ‘Caring for Your Introvert’ which tackles many of the issues Cain does but with a lightness that’s lacking in her book. He says, for example, “Remember, someone you know, respect and interact with every day is an introvert, and you are probably driving this person nuts.” Cain says the same but not quite as memorably. In her review for The New York Times Judith Warner said that Quiet is “a long and ploddingly earnest book [which] would have greatly benefited from some of [Rauch’s] levity. (That’s where I learned about Rauch by the way.) That doesn’t mean that Cain’s isn’t eminently quotable and Goodreads has several pages devoted to quotes from the book like:

Love is essential, gregariousness is optional.

and

Naked lions are just as dangerous as elegantly dressed ones.

On Goodreads 74% give the book a rating of 4-stars or higher (on Amazon the figure is 85%) and I can see why the book is popular. There’s a website to go with the book on which there’s a quiz to check if you’re an introvert or an extrovert. Apparently I’m a Strong Introvert. I guess it depends on how you phrase the questions, eh? Now I am being cynical. Jon Ronson in his review for The Guardian also took the test. This is what he reports:

I do the test. I answer "true" to exactly half the questions. Even though I'm in many ways a textbook introvert (my crushing need for "restorative niches" such as toilet cubicles is eerie) I'm actually an ambivert. I do the test on my wife. She answers true to exactly half the questions too. We're both ambiverts. Then I do the test on my son. I don't get to the end because to every question – "I prefer one-on-one conversations to group activities. I enjoy solitude …"– he replies: "Sometimes. It depends." So he's also an ambivert.

If she’s included a ‘Sometimes’ option there’s no doubt what I would’ve been too.

I can’t say I didn’t enjoy much of this book but it is overly long and I’m not just saying that because I don’t like long books. There is a lot of good stuff here and if you come across a cheap enough second-hand copy and are unhappy with your introversion (key phrase here) then you may well find what she has to say helpful. If, like me, you don’t find being who you are a burden and aren’t obsessed with labelling yourself then maybe this one isn’t for you.  Being who I am can be a minor inconvenience at times but that’s about the worst I can say. It would be helpful if I was more outgoing—I might sell some more damn books for starters (in that respect Cain is a shining example of how to get over yourself and get out there and promote)—but then I wouldn’t be me and I don’t hate being me; I hate others for making me feel that I could improve on being me. Maybe I could. But at what cost?

Being who I am can be a minor inconvenience at times but that’s about the worst I can say. It would be helpful if I was more outgoing—I might sell some more damn books for starters (in that respect Cain is a shining example of how to get over yourself and get out there and promote)—but then I wouldn’t be me and I don’t hate being me; I hate others for making me feel that I could improve on being me. Maybe I could. But at what cost?

Last word: my wife recently returned from America and had a couple of pressies for me. One was a T-shirt with the interjection meh. on it. She knows me well.