Pinter’s not a poet, but he doesn’t know it. – Daniel Finkelstein, The Times, 16 March 2005

In August 1950 two poems appeared in Poetry London 5—'New Year in the Midlands' and 'Chandeliers and Shadows'—both accredited to a new poet to the market[1], one Harold Pinta. This was not a typo although "stanzas from the two published poems were interchanged"[2] which must have been upsetting for the nineteen-year-old poet and I can imagine how he might have felt since my first published poem appeared sans title. Pinter had opted to use the pseudonym 'Pinta' "largely because one of his aunts was convinced—against all the evidence[3]—that the family came from distinguished Portuguese ancestors, the da Pintas,[4] an odd choice since, in the UK at least, everyone would have looked at 'Pinta' and read it as in 'pint of milk', at least I did.

So, like his long-time friend and mentor, Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter began and ended his career as a writer writing poetry.

Speaking on BBC Radio 4's Front Row, the seventy-four-year-old said: "I think I've stopped writing plays now, but I haven't stopped writing poems."

"I think I've written twenty-nine plays. I think it's enough for me. I think I've found other forms now."[5]

He died when he was seventy-eight. Pinter's earliest influences were Yeats and Dylan Thomas. In his twenties he was very much taken by the poetry of WS Graham (with whom he became friends)—which he described as "ravished by language and the conundrum of language."[6] Later still, of all people, Philip Larkin's poetry called out to him:

In the 1960s, Philip Larkin was surprised that Pinter was an enthusiastic (and influential) advocate of his poetry. Since the plays were 'rather modern', he wrote to Pinter, 'I shouldn't have thought my grammar school Betjeman would have appealed to you.' Unlike Pinter [who went to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (an institution he found intolerable)], Larkin had been to Oxford, where he learned that the mixing of Modern and Traditional was 'not done'.[7]

Pinter's output was not huge—his Collected Poems and Prose (from 1996)—only contains forty-six poems. The twenty-four-page War (2003) adds another handful to this list (the book consists of a speech, seven poems written immediately before the 2003 Iraq war, and one poem on the 1991 Gulf War) plus the Six Poems for A in 2007. So, less than a hundred still available in print although the complete total is probably not much higher. About the same as Beckett then. It is easy to see how the poetry of these two great writers could get passed over.

The question is: Just because Pinter is a great playwright does that automatically make him a great poet? The answer is obviously no but surely you would expect a talented wordsmith like Pinter to at least write decent poetry. Not everyone thinks so. Here is an excerpt from the 2004 TS Eliot lecture 'The Dark Art of Poetry' in which Don Paterson does not mince his words:

The way forward, it seems to me, lies in the redefinition of ‘risk’ To take a risk in a poem is not to write a big sweary outburst about how dreadful the war in Iraq is, even if you are the world’s greatest living playwright. This poetry is really nothing but a kind of inverted sentimentalism—that’s to say by the time it reaches the page, it’s less real anger than a celebration of one’s own strength of feeling. Since it tries to provoke an emotion of which its target readers are already in high possession, it will change no-one’s mind about anything; more to the point, anyone can do it.[8]

Pinter's response? Surprisingly restrained:

True to form, the playwright reacted with some asperity to Paterson's analysis. "You want me to comment on that?" he said from his west London home. "My comment is: 'No comment.' "[9]

The poem I imagine Paterson is referring to is this one:

American Football

(A Reflection upon the Gulf War)

Hallelullah!

It works.

We blew the shit out of them.

We blew the shit right back up their own ass

And out their fucking ears.

It works.

We blew the shit out of them.

They suffocated in their own shit!

Hallelullah.

Praise the Lord for all good things.

We blew them into fucking shit.

They are eating it.

Praise the Lord for all good things.

We blew their balls into shards of dust,

Into shards of fucking dust.

We did it.

Now I want you to come over here and kiss me on the mouth.

Okay, it's not pretty poem but the subject matter is not pretty. It was famously rejected for publication by the Independent, the Observer, the Guardian (on the grounds it was 'a family newspaper'), the New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books. Andrew O'Hehir, in his review of Various Voices: Prose, Poetry, Politics, writes:

If the dense and difficult poems of his youth are often too clever by half, they nonetheless display a mind rich with images and a remarkable facility with language. Recent poems like ''American Football' or 'Death' have an almost electrical clarity and intensity.[10]

Michael Billington reproduces the poem in his book Life and Work of Harold Pinter and has this to say about it:

What Pinter is clearly doing in American Football is satirising, through language that is deliberately violent, obscene, sexual and celebratory, the military triumphalism that followed the Gulf War and, at the same time, counteracting the stage-managed euphemisms through which it was projected on television. […] Pinter's poem, by its exaggerated tone of jingoistic, anally obsessed bravado, reminds us of the weasel-words used to describe the war on television and of the fact that the clean, pure conflict which the majority of the American people backed at the time was one that existed only in their imagination. Behind the poem lies a controlled rage: that it was rejected, even by those who sympathised with its sentiments, offers melancholy proof that hypocrisy is not confined to governments and politicians.[11]

Michael Wood, however, in his review of Billington's book, said he thought the poem "truly dire"[12] and was not swayed by Billington's arguments:

Billington’s piety about Pinter is all but crippling, turning what might have been a portrait into a long obeisance.[13]

Have you ever listened to American GI's talk? I imagine the same can be said for all soldiers. They are a foul-mouthed bunch. I found an old newspaper clipping from 1916 going on about the language used by the troops. Apparently Joan of Arc complained about how the English solders cussed back in the late middle ages. Of course we have no idea who the narrator is in this poem. I suspect the 'me' in the final line is Mom since we all know the slang expression, 'You kiss your momma with that mouth?' “We’re fighting for mom and apple pie.” That’s what the American GI’s often said when asked what they were fighting for during World War II. Either that or for God and country. And, of course, that really underlines the satire here.

Have you ever listened to American GI's talk? I imagine the same can be said for all soldiers. They are a foul-mouthed bunch. I found an old newspaper clipping from 1916 going on about the language used by the troops. Apparently Joan of Arc complained about how the English solders cussed back in the late middle ages. Of course we have no idea who the narrator is in this poem. I suspect the 'me' in the final line is Mom since we all know the slang expression, 'You kiss your momma with that mouth?' “We’re fighting for mom and apple pie.” That’s what the American GI’s often said when asked what they were fighting for during World War II. Either that or for God and country. And, of course, that really underlines the satire here.

Over on his site Nigeness, Nige finishes his remarks following Pinter's death with this final comment:

As for Pinter's 'poetry'—had it been written by anyone else, it would surely never have been taken seriously for a moment, would it?[14]

It's a fair question and I have to say that if anyone else had sent in that poem to those esteemed newspapers they wouldn't have even received any reply let alone the polite rejections Pinter mentions in his article 'Blowing up the Media' which first appeared in Index on Censorship and is reproduced on his website here.

Paterson is, of course, entitled to his opinion (as are all the others) but his real problem with Pinter's poetry stems from Paterson's definition of what poetry is. I don't support the school of thought that says, "It's a poem because I say so," but I do argue for a broad definition of poetry. I think poetry can, for example, be ugly and I see no fundamental difference between Pinter's 'American Football' and John Cooper Clarke's'Evidently Chickentown'. The tone is different but the underlying message in John Cooper Clarke's poem is every bit as serious and heartfelt as is Pinter's. Now just try and imagine John Cooper Clarke reading 'American Football'. The singer-songwriter PJ Harvey cites Pinter's poetry as a source of inspiration:

I'm inspired by the other great writers I go back to and read again and again, and think how did they do that?"

Such as? She indicates a volume of Harold Pinter's poetry that she has brought with her. "Pinter leaves me speechless. Just unbelievable. A poem like 'American Football' or 'The Disappeared'.[15]

Do I like this poem? No, I can't say I do, but since when has a poem's likeability been the sole criterion by which we judge its quality? I'm not fond of its scatological language and yet, in my own anti-war poem I have a dog peeing at the base of a monument erected to commemorate fallen heroes so I can see exactly where Pinter is coming from here, besides, for some strange reason, other than 'pissed off', there aren't nearly as many vulgar expressions referencing urine as there are faeces.

In her biography on Voltaire, Evelyn Beatrice Hall wrote the phrase: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it" and Hall's quote is often cited to describe the principle of freedom of speech, something about which Americans in particular are highly vocal. I'm not here to defend Pinter's politics but I am here to defend his poetic choices. And choice is the keyword here. Artists frequently simplify their style (take the naïve artists as an example) not because that's the best they can do but because that style is intended to have a certain effect. I believe the same is true in Pinter's choice to use coarse and frankly unpoetic language here.

In his essay 'Introduction to Pinter's Poetry' Jean-Marie Gleize says that for Pinter "especially in the last few years, a poem could be an in-your-face, very violent and heavily charged platform, and that a poem could work as a weapon, a weapon of attack, a combat weapon."[16] And if you have nothing left bar words and shit, well just ask the prisoners in the Maze prison in the mid-seventies how effective they can be.

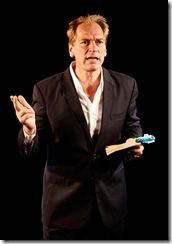

Here's a selection of Pinter's war poetry opening with a powerful rendition of 'American Football' by Michael Sheen (which perfectly captures the "yee-haw apocalypse mandated by religious bigotry and bloodlust"[17] tone of poem) but hang on for Gina McKee's beautiful rendition of the (to my mind) rather Owen-esque 'Meeting' at the end:

Let's have a look at a very different poem now, a love poem, written the year before he wrote 'American Football' for his second wife Dame Antonia Fraser:

It Is Here

(For A)

What sound was that?

I turn away, into the shaking room.

What was that sound that came in on the dark?

What is this maze of light it leaves us in?

What is this stance we take,

to turn away and then turn back?

What did we hear?It was the breath we took when we first met.

Listen. It is here.

They had been together about fifteen years when he wrote the poem and she admits that it is "nostalgic for when we first got together,"[18] a poem celebrating requited married love.The poem recalls the coup de foudre at Pinter's first meeting with his future wife and, of course, it will never mean as much to anyone else but that doesn't make it a bad poem; it is a personal poem and if anyone else gets anything out of it then bully for them.

It is interesting to hear him read the poem (which you can here (and then compare it to Antonia Fraser's interpretation)) because he doesn't read it like any love poem you have ever heard before. There's no sentimentalism here.

Here are three more poems written for his wife:

Here's what Pinter had to say about why he was a fan of Beckett's work:

The farther he goes the more good it does me. I don’t want philosophies, tracts, dogmas, creeds, ways out, truths, answers, nothing from the bargain basement. He is the most courageous, remorseless writer going and the more he grinds my nose in the shit the more I am grateful to him. He’s not fucking me about, he’s not leading me up any garden path, he’s not slipping me a wink, he’s not flogging me a remedy or a path or a revelation or a basinful of breadcrumbs, he’s not selling me anything I don’t want to buy—he doesn’t give a bollock whether I buy or not—he hasn’t got his hand over his heart. Well, I’ll buy his goods, hook, line and sinker, because he leaves no stone unturned and no maggot lonely. He brings forth a body of beauty. His work is beautiful. (italics mine)[19]

One could say the same of Pinter. It doesn't matter what Pinter is talking about, be it love or war, he never has his hand over his heart; he's not that kind of writer. He was certainly an angry young man—he's sometimes linked with that group—and he died an angry old man but as his wife pointed out:

There was never any rage or anger of the 'Where's my shirt?' variety. Harold for all his combativeness is completely unexplosive.[20]

For me one of his most powerful poems is actually a found poem. It's called 'Death' and was written just after the registration of his father's death at Hove Town Hall in 1997:

Death

(Births and Deaths Registration Act 1953)

Where was the body found?

Who found the dead body?

Was the dead body dead when found?

How was the dead body found?

Who was the dead body?

Who was the father or daughter or brother

Or uncle or sister or mother or son

Of the dead and abandoned body?

Was the body dead when abandoned?

Was the body abandoned?

By whom had it been abandoned?

Was the dead body naked or dressed for a journey?

What made you declare the dead body dead?

Did you declare the dead body dead?

How well did you know the dead body?

How did you know the body was dead?

Did you wash the dead body?

Did you close both its eyes?

Did you bury the body?

Did you leave it abandoned?

Did you kiss the dead body?

Don't you find it strange that the love poem for his wife is written in the same interrogatory style? At first it's a son's lament over the loss of his father but later one he chose to end his booklet War with—for which he was awarded the Wilfred Owen Poetry Award—minus the subtitle and the date. Suddenly the poem takes on a whole different meaning.

But could Pinter write a real poem? Certainly his early derivate verse was but what about later on? Here's one from 2006 which looks fairly real to me if you don't mind overlooking the aside in the final stanza. Hell, it even (half-) rhymes:

Lust

There is a dark sound

Which grows on the hill

You turn from the light

Which lights the black wall.

Black shadows are running

Across the pink hill

They grin as they sweat

They beat the black bell.

You suck the wet light

Flooding the cell

And smell the lust of the lusty

Flicking its tail.

For the lust of the lusty

Throws a dark sound on the wall

And the lust of the lusty

– its sweet black will –

Is caressing you still.

Or what about this one from 1998 with its alliteration and internal rhymes?

The Disappeared

Lovers of light, the skulls,

The burnt skin, the white

Flash of the night,

The heat in the death of men.

The hamstring and the heart

Torn apart in a musical room,

Where children of the light

Know that their kingdom has come.

Surely this rhymer counts?

Body

Laughter dies out but is never dead

Laughter lies out the back of its head

Laughter laughs at what is never said

It trills and squeals and swills in your head

It trills and squeals in the heads of the dead

And so all the lies remain laughingly spread

Sucked in by the laughter of the severed head

Sucked in by the mouths of the laughing dead [21]

And what about this frankly playful (and yet still very serious) one from the same year?

Order

Are you ready to order?

No there is nothing to order

No I'm unable to order

No I'm a long way from order

And while there is everything,

And nothing, to order,

Order remains a tall order

And disorder feeds on the belly of order

And order requires the blood of disorder

And "freedom" and ordure and other disordures

Need the odour of order to sweeten their murders

Disorder a beggar in a darkened room

Order a banker and a castiron womb

Disorder an infant in a frozen home

Order a soldier in a poisoned tomb

Now this one sounds like Pinter. There is a common thread that runs between this poem, 'Death' and 'American Football' and Noel Malcolm hits the nail on the head in his review of War:

Pinter's poetry tends anyway to work by repetition and amplification, so such devices as this are well suited to it, generating incremental unease.[22]

Was Pinter a poet? In his obituary in The Guardian Michael Billington—who we have seen already was a fan—opens with:

Harold Pinter, who has died at the age of 78, was the most influential, provocative and poetic dramatist of his generation. He enjoyed parallel careers as actor, screenwriter and director and was also, especially in recent years, a vigorous political polemicist campaigning against abuses of human rights. But it is for his plays that he will be best remembered and for his ability to create dramatic poetry out of everyday speech. (italics mine)[23]

The word 'poetry' or some variation thereof appears several other times in the article although he's certainly not the only one to use the adjective 'poetic' when talking about Pinter's plays. William Baxter writes:

I think his greatest poetry is in the drama. His plays are full of wonderful poetry whether it's topographical with long reflections on the landscapes of London, or whether it is reflections on the past or what may not have occurred between two human beings.[24]

A poet is not simply someone who writes poetry. Poetry is bigger than that and I do get frustrated by those who want to bottle it and market it. I am with Todd Swift who wrote to The Guardian in response to their article covering Don Paterson's speech and said (in part):

Paterson is wrong because he is so intent on limiting what a poem can and should be. In fact, it is when poetry (or music) is evolving and dynamically open to a rich variety of different voices that it thrives best. Political poetry has always been one part of poetry's role, and Pinter's work, although urgently blunt, is in that tradition.[25]

Will Pinter's poetry be remembered for as long as his plays? Doubtful but it's really only timeless writing that manages to survive. Topical writing and satire rarely lasts longer than the decade it was written in, certainly not the generation. A poem's greatness—its worthiness if you like—has little to do with whether or not the public take it to their heart—few of them could tell a good poem from a bad one but they know what they like, what moves them—and so I could see 'Death' lasting, maybe even 'It is Here'; there are certainly enough copies of the latter kicking around online and now I've added one more.

Pinter's verse is … about process; it's Pinter acting out, as it were, the contrary facts of being inside the situation, the context of the poem, the context of the politics. It is in essence dramatic and vatic; read it out loud, and work your way through the fissures to get at the tissue of the man. Pinter is never about epiphany and revelation, and much more about concealment. Despite the surface of the language, the poems are essentially about withholding something. The language of the poems can be thin and etiolated, straightforward too; like Carver's it can be artless, and where Carver derided cheap tricks, one can feel that Pinter, too, was after something direct, intimate and oral. He wanted to get under our skin as quickly as possible. To get in, and do the job.[26]

I've not touched on his poetry about cricket (which he adored) as I know nothing about the subject. "Cricket is the greatest thing God created on earth," Pinter once said. "Certainly greater than sex, although sex isn't too bad either."[27] I really don't get this "mini-masterpiece",[28] for example:

I saw Len Hutton in his prime

Another time

another time

I suppose it would help if I knew who Len Hutton was.

There is quite a bit of poetry on Pinter's website and I would recommend spending a little time reading through what's there; the poems themselves and the various analyses by others.

In 2005 Pinter contacted the actor Julian Sands and "asked him to read a few at a charity event (Pinter's throat cancer was by then too  advanced for him to read them himself, but he worked with Mr Sands to get the right tempo and pitch)."[29]

advanced for him to read them himself, but he worked with Mr Sands to get the right tempo and pitch)."[29]

“He was feeling his mortality very keenly and wanted these poems to reveal his interior,” remembers Sands. “He relished every moment with words, and wanted me to get it absolutely right. In spite of his illness, he had a burning energy. He was still on fire.”[30]

After Pinter's death Sands read the poems for a group of friends including his fellow actor John Malkovich who felt the tribute could be adapted for a wider audience and set about working with Sands to develop a show which, in 2011, premiered at the Edinburgh Festival. He then took it all over the world. I guess there's a market for "doggerel".[31]

Let me conclude with a poem of my own. Oddly, in recent years—I say 'oddly' because this is not something I did as a young poet—I've written a number of poems in the voices of other poets (Larkin, Bukowski, Cummings, Jenny Joseph). Here is my poem in Pinter's voice:

After Pinter

I am a great man.

People depend on me to say great things.

They expect me to say great things.

I expect I am saying something great right now.

Things appear greater when I say them.

It is a terrible burden, of course,

a terrible responsibility, in fact,

to always have to say something great,

to be great to order; that said

people believe I am being great

even when I am being normal.

To them my normal is just great.

They need me to be great

ergo I am great.

“That was great,” they’ll say

and they’ll believe that to be true

but at the same time they’ll be thinking:

I thought great might be greater than that

but what do I know, he’s the great man, not me.

Wednesday, 27 January 2010

Finally, here are some links to Pinter's poetry online:

REFERENCES

[1] His first publication was a poem 'Dawn' which appeared in the Hackney Downs School Magazine in the spring of 1947.

[2] Michael Billington, The Life and Work of Harold Pinter quoted on HaroldPinter.org

[3] Research by Antonia Fraser revealed the legend to be apocryphal; three of Pinter's grandparents came from Poland and the fourth from Odessa, so the family was Ashkenazic.

[4] Michael Billington, The Life and Work of Harold Pinter quoted on HaroldPinter.org

[5]'Pinter to give up writing plays', BBC News, 28 February 2005

[6] From the preface to W.S. Graham The Nightfisherman: Selected Letters, edited by Michael and Margaret Snow quoted on HaroldPinter.org

[7] Ian Smith ed., Pinter in the theatre, pp.17,18

[8] Don Paterson, 'The Dark Art of Poetry', The TS Eliot Lecture 2004, 9 November 2004

[9] Charlott Higgins, 'Pinter's poetry? Anyone can do it', The Guardian, 30 October 2004

[10] Andrew O'Hehir,The New York Times, 9 May 1999

[11] Michael Billington, The Life and Work of Harold Pinter quoted on HaroldPinter.org

[12] Michael Wood, 'Nice Guy', London Review of Books, 14 November 1996

[13]Ibid

[14] Nige, 'Harold and Eartha', Nigeness, 29 December 2008

[15] PJ Harvey quoted in Dorian Lynskey, 'PJ Harvey: "I feel things deeply. I get angry, I shout at the TV, I feel sick"', The Observer, 24 April 2011

[16] Jean-Marie Gleize, 'Introduction to Pinter's Poetry' in Brigitte Gauthier ed., Viva Pinter: Harold Pinter's Spirit of Resistance, p.133

[17] David Wheatley, 'Dichtung und Wahrheit: Contemporary War and the Non-Combatant Poet' in Tim Kendall ed., The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry, p.660

[18] From an audio recording of the poem on YouTube

[19] Harold Pinter, Various Voices: Prose, Poetry Politics, p.58 quoted (in part) in Jean-Marie Gleize, 'Introduction to Pinter's Poetry' in Brigitte Gauthier ed., Viva Pinter: Harold Pinter's Spirit of Resistance, p.133

[20] Dame Antonia Fraser quoted in Penelo Prentice, The Pinter Ethic: The Erotic Aesthetic, p.ciii

[21] Several copies of this can be found online entitled 'Laughter' but it was actually called 'Body' when it first appeared in print in the Saturday Guardian on 25 November 2006. See William Baxter, Harold Pinter, p.137

[22] Noel Malcom, 'Stanzas and sound-bites', The Telegraph, 7 July 2003

[23] Michael Billington, 'Harold Pinter', The Guardian, 25 December 2008

[24] William Baxter, 'Pinter's poetry: a topological corpus' in Brigitte Gauthier ed., Viva Pinter: Harold Pinter's Spirit of Resistance, p.136

[25] Todd Swift quoted in 'Poets at war over Pinter and politics', The Guardian, 2 November 2004

[26] Christopher Hamilton-Emery, 'Pinter's poetry got under the skin', The Guardian, 30 December 2008

[27] Quoted in 'Harold Pinter's stroke of genius in the dullest passages of play', The Telegraph, 16 January 2009

[28]'Harold Pinter and the art of cricket poetry', an extract from The Guardian's weekly e-mail The Spin, 1 November 2011

[29]'The known and the unknown: A celebration of a bullish bard', The Economist, 20 August 2011

[30] Charlotte Stoudt, 'The poetry of Harold Pinter, in a benefit for the homeless', Los Angeles Times, 8 December 2009

[31] Andy Croft, 'Pure doggerel', The New Statesman, 6 December 2004

Harold Pinter

Harold Pinter