Beyond a certain point one cannot reconcile the demands of translation and of poetry, and one must opt for one or the other – A.C. Graham, introduction to Poems of the Late T’ang

A while ago I reviewed The Jaguar’s Dream which is a collection of, to put it simply, translations into English of poems from a variety of eras and languages. The poems were translated by the Australian poet John Kinsella who is not a professional translator but tackled the job purely for the pleasure of doing so. In several of his poems I found things I would have done differently. A simple example is his decision in his version of Supervielle’s‘La Mer Secrète’ to translate ‘Elle est ce que nous sommes’ as ‘It is what we become’. It is not wrong since French has no neuter; something which has always bothered me. Who decided that the sea was female? I wrote about it five years ago in my post French computer sex and have yet to find an answer to the question. Of course in prose I would have been perfectly fine with Kinsella translating elle as ‘it’ but poetry is another ballgame completely. My take on the poem is that Supervielle is using personification here and treating the sea as if she were a woman, which is perfectly feasible, but how would we ever know?

I only studied French for two years at school (and Latin for one). I would have quite liked to have continued my studies but I wanted an O-Level in Music far more. Besides all that was forty years ago. So I am a long way away from what little I did learn but some of it stuck enough to know when the subtitles are wrong on TV. On the whole though I’ve never given the subject of translation much thought over the years. I’ve read books in translation and assumed that as the men and women who were getting paid to do the job they knew what they were doing. Always been a bit naïve me. Since I’ve started doing book reviews though and noticing how some translations get praised over others it has made me curious.

The title of this post refers to the song by George and Ira Gershwin and the novel by Albert Camus. When I read The Outsider in my late teens I assumed that that was the book’s title and it came as a great surprise to me to learn that my American cousins call the selfsame book, The Stranger. The title in French is, of course, L’Étranger which, admittedly, looks like ‘stranger’ but I’m told that there isn’t a equivalent expression in English and that étranger means something  between ‘stranger’ and ‘outsider’ whatever that may be. Why, I wonder, did English not simply absorb the word as it has done with so many foreign expressions like vis-à-vis, tête-à-tête and mano-a-mano?

between ‘stranger’ and ‘outsider’ whatever that may be. Why, I wonder, did English not simply absorb the word as it has done with so many foreign expressions like vis-à-vis, tête-à-tête and mano-a-mano?

I enjoyed doing research to support my review of The Jaguar’s Dream and thought it might not be such a bad idea to have a crack at translating myself so I typed ‘poésie française moderne’ into Google and picked the first poem that wasn’t too long. It turned out to be an extract from ‘Art poétique’ by Eugène Guillevic of whom I knew nothing. I cut and pasted the poem into a Word document and began. Here is the original and what Google Translate made of it:

Art poétique (extract) | Poetic Art If I pour sand |

Okay we all know that Google Translate is going to mangle the text but for the purpose of a cursory read it does okay; you get the gist. We had a guy pouring sand from one hand into the palm of his other hand. It’s a pleasurable experience and a metaphorical one from all accounts but even just having a quick glance it’s obvious that there is a lot missing here.

The title was the easy bit. Ars Poetica is a Latin term meaning “The Art of Poetry” or “On the Nature of Poetry”.

The first problem I had was determining what the sentences were. On the surface it looks like the first five stanzas make up one long sentence leaving only a short sentence in the final stanza. I suspected that whoever had transcribed the poem had made mistakes. They hadn’t. This is how that opening sentence is translated by Google once all the line breaks are removed:

If I pour sand in my left hand to my right palm, it is of course for the pleasure of touching the stone became dust, but also and more to give body to the time, so feel time flowing , drain and also do go back, denying oneself.

What’s obvious here is that Google Translate treats every line as a sentence and that affects the translation more than one might expect. We see this in line four where the line is translated ‘the course’ whereas the sentence opts for the idiom ‘of course’ which makes all the difference. The same goes for line eight where Couler, s'écouler is translated as ‘Flow, flow’ rather than ‘flowing, drain’. Couler means ‘flow’ or ‘run’ or ‘cast’ or ‘roll’, even ‘smear’. Écouler means ‘sell’ or ‘dispose of’ so ‘drain’ wouldn’t be such a bad translation.

What’s obvious here is that Google Translate treats every line as a sentence and that affects the translation more than one might expect. We see this in line four where the line is translated ‘the course’ whereas the sentence opts for the idiom ‘of course’ which makes all the difference. The same goes for line eight where Couler, s'écouler is translated as ‘Flow, flow’ rather than ‘flowing, drain’. Couler means ‘flow’ or ‘run’ or ‘cast’ or ‘roll’, even ‘smear’. Écouler means ‘sell’ or ‘dispose of’ so ‘drain’ wouldn’t be such a bad translation.

Line six was the first one I struggled with:

For / to | give | of / the | body | at the / to the | time |

Du is a contraction of the words “of” and “the”. Au is a contraction of the words “at” or “to” and “the”. So is it ‘to give the body time’ or ‘to give [the] body to the time’. That annoying little preposition makes all the difference. In the first instance we’re simple allowing the body time to experience the flow of the sand but in the other suggests a dedication of the body especially since donner can mean ‘donate’. People given themselves to God or they give of themselves to others. It’s the difference between listening to music and giving oneself to the music. Or do we have a situation here like we have with L’Étranger? is Guillevic covering all his bases here, the physical and the, for want of a better word, the spiritual?

I found the fifth stanza particularly troublesome:

And | also | the | do / be | return | in / to | back | to himself | deny |

I decided to have a look at some other translations:

nous avons souvent souhaité faire revenir le temps en arrière

we often want to return time backrevenir en arrière pour faire les choses différemment

go back and do things differently

The notion of turning back time is a common one whether we’re talking literally as in The Time Machine or metaphorically. Renier is a verb that means to deny, renounce, disown, repudiate or, more specifically if preceded by se, deny oneself. What is the narrator saying here? If we turn back time then we are denying ourselves what? We have time in the form of grains of sand trapped in our hand. We can metaphorically halt the flow of time whenever we want to.

The last line is easy. It’s practically a transliteration: J'écris un poème contre le temps– I write a poem against time. But the penultimate line made me hesitate again.

In | by | slip | of | sand |

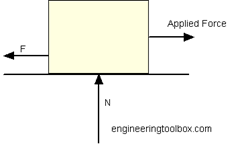

Faisant is the present participle of faire. Glisser—think glissando—means to slip, slide or even skid. Context dictates it won’t be ‘skid’ but I was curious why Google Translate threw up ‘dragging’ and I wondered whether or not the poet was suggesting we tighten our fist so that time drags, another common English idiom. In a computer manual they have the expression “Soit en faisant glisserl'appareil sur ce dernier”. Is 'faisant glisser' equivalent to the  concept of 'dragging' an item with the mouse? Probably. But do we really drag an icon? I’m thinking back to my Applied Mechanics days and the good old coefficient of friction. We slide things about the screen; we don’t drag them. Sand, however, would provide resistance. Sand has a friction coefficient of 0.60. Or am I getting carried away here? Perhaps.

concept of 'dragging' an item with the mouse? Probably. But do we really drag an icon? I’m thinking back to my Applied Mechanics days and the good old coefficient of friction. We slide things about the screen; we don’t drag them. Sand, however, would provide resistance. Sand has a friction coefficient of 0.60. Or am I getting carried away here? Perhaps.

This is what I settled on:

The Art of Poetry

If I pour sand from my left hand

into the palm of my right hand

the sensation is most pleasant.

Time has turned these stones into dust.

But there’s something else, something more,

which affords me the option to

experience time flow and run

out. Stop. Go back. Deny yourself.

Letting sand slip through my fingers

I write a poem against time.

I decided not to go for a literal translation for the most part but to get under the skin of the poem. At the same time I didn’t want to impose my own (possibly) narrow interpretation:

Every language, Guillevic tells us, is foreign. “Foreign, yes, because words are not made for the use they have in a poem. It’s the work of the poet … to make them say something different from what they would commonly say, by themselves.” – ‘Carnac and Living in Poetry’, James Sallis, Boston Review, October / November 2000

The question begs to be asked: Is it possible to do justice to any author unless you are familiar with more than just the poem you have in front of you? On the Bloodaxe site it says this about Guillevic:

For Guillevic, the purpose of poetry is to arouse the sense of Being. In this poetry of description—where entire landscapes are built up from short, intense texts—language is reduced to its essentials, as words are placed on the page ‘like a dam against time’. When reading these poems, it is as if time is being stopped for man to find himself again.

That, for me, is a significant comment especially when examining a poem about the nature or art of poetry. Since I couldn’t find an English translation of the poem online (although I did run across a Russian one of all things) I decided to order a copy of Ars Poetica and while I was waiting on it arriving in the post did some research to see what I could find out about Guillevic.

Eugène Guillevic (Carnac, Morbihan, France, August 5, 1907, Carnac – March 19, 1997, Paris) was one of the better known French poets of the second half of the 20th century. Professionally, he went under just the single name "Guillevic". – Wikipedia

Wikipedia lists 38 books. Predictably very little has ever been translated into English. I found four: Carnac (1961), Geometries (1967), The Sea & Other Poems (a compilation to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth), Selected Poems of Guillevic and, fortunately for me, Art Poétique (1985-86). Auster’s The Random House Book of Twentieth-Century Poetry does, however, include nine poems translated by Savory, John Montague, and Levertov. James Sallis, writing in The Boston Review, doesn’t find this deficiency surprising:

Wikipedia lists 38 books. Predictably very little has ever been translated into English. I found four: Carnac (1961), Geometries (1967), The Sea & Other Poems (a compilation to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth), Selected Poems of Guillevic and, fortunately for me, Art Poétique (1985-86). Auster’s The Random House Book of Twentieth-Century Poetry does, however, include nine poems translated by Savory, John Montague, and Levertov. James Sallis, writing in The Boston Review, doesn’t find this deficiency surprising:

What is at the very heart of his work’s excellence—the simplicity of its diction, the unadorned language, its very modesty—renders it all but untranslatable. Even in French, Guillevic can be an elusive read. Slight, elliptical, gnomic, the poems vanish when looked at straight on. "Les mots / C’est pour savoir," he says. Words are for knowing. And by les mots he means, resolutely, French words. Because their mystery, their magic, is in the language itself, these poems do not easily give up their secrets, or travel well. They are their secrets. They crack open the dull rock of French and find crystal within. In English, all too often, only the dullness, the flatness, remains.

Wikipedia’s brief entry has only this to say about his actual writing:

His poetry is concise, straightforward as rock, rough and generous, but still suggestive. His poetry is also characterized by its rejection of metaphors, in that he prefers comparisons which he considered less misleading.

A poet who eschews metaphors. Interesting. His first book was Requiem which was published rather late, in 1938, by Tschann. He worked in the Ministry of Finance (rising to Inspecteur d'Economie Nationale). His obituary in The Independent says:

This career, with all its legal and administrative rigour, had a decisive effect upon his poetry, enabling him to discard all "poeticality" and "rigmarole rhyming". He became a firm disciple of the Object, and disdained the Surrealists' new-fangled obsession with the Image.

And Sallis again:

Alterity may be Guillevic’s obsessive theme. He is, of course, among the most outward-directed and least subjective of poets, so it’s only inevitable that soon he’d fetch up against the world’s blank face and lack of affect. However stubbornly we confront or make demands upon them, the world and its things remain unknowable. In a poem from his second collection, Exécutoire, he writes: "To see inside walls / Is not given us. / Break them as we will / Still they remain surface." Like the sea.

I said that Guillevic is a French poet and that is true but French was not his first language. In her introduction to Selected Poems of Guillevic the American poet Denise Levertov notes:

It is curious to note that, outside school, Guillevic did not hear French spoken around him, but, in early childhood, Breton, and in adolescence, Alsatian, until he was nearly twenty. Jean Tortel … speculates on the possible influence on his work of this early detachment from the language from which he writes; perhaps, he suggests, it helped to form “the consideration from which he approaches words, the space he leaves between them and himself. For him each vocable (plate, chair, nightingale) is not something to be taken for granted, something everyday.” One might say, indeed, that his relation to words is truly phenomenological…

Levertov is very honest as regards her own efforts:

I am not fully satisfied, by any means, with most of my versions of Guillevic; but A.C. Graham’s definition of the translator’s choices [quoted, in part, at the top of this article] does describe my intention, which has been to render these poems in such a way that they would seem, in English, to be written in the language of poetry and not Translationese.

and even in a tiny poem like this she need to qualify one of her choices:

The little trout

slim1 as a penknife

can’t find its rock

in the great brook.1 Literally, “the size of.” (D.L.)

The book arrived quicker than I expected so I’m going to leave this here. I think I may well do a full article on Guillevic at a later date. I was keen, nonetheless, to see what Maureen Smith had made of this extract. Smith lives in France where she was a professor of English and American Literature until she retired in 2002. She is trilingual and her specialism is contemporary poetry. She has written articles in English, French and Spanish on contemporary writers and painters.

Here is her translation of this excerpt:

If I pour some sand

From my left hand to my right palm,

It’s of course for the pleasure

Of touching powdered stone,

But it’s also and more so

To give a body to time,

So as to feel time

Trickling, passing by

And also to make it

Turn back, retract.

By making some sand slip by,

I’m writing a poem against time.

Is her translation right? I never thought of using ‘retract’ nor did I see that he was talking about making time turn back (although I did wonder about it above) but it’s quite obvious here. I’m not sure about her use of ‘some’ in the penultimate line but I see that she’s gone with giving ‘a body to time’ which I wasn’t sure about.

All in all I’m not displeased with my effort. I think I’ve done a little more than translate. I’ve also partly interpreted (i.e. imposed my interpretation) and that could be viewed as a weakness; I know I said above that I tried not to but I don’t think I tried hard enough. I do think Smith’s missed something by simply talking about sand as ‘powdered stone’ though. What is it has turned the stone into powder? Okay, it’s the sea, but it’s the sea over time. After having a think about it I decided to change one line and add in a couple of tweaks. Here is my final (for the moment) version:

If I pour sand from my left hand

into the palm of my right hand

the sensation is most pleasant.

Time has turned these stones into dust

but there’s something else, something more,

which affords me the option to

experience time flow and run

out or stop and turn back the clock.

Letting sand slip through my fingers

I write a poem against time.

I’ve removed the title because now I have the book I can see that the whole book is really one long poem made up of tiny fragments like this.

I’ve removed the title because now I have the book I can see that the whole book is really one long poem made up of tiny fragments like this.

This has been an enjoyable exercise and I may do it again. I’m certainly glad I discovered this poem and have John Kinsella to thank for that. So I’ll let him have the final say. Here is a link to his poem ‘I read Guillevic's Carnac’.