The Plot Never Thickens – title of a New York Timesarticle on Handke

The Left-Handed Woman exists in two states, as a screenplay and a novella, both written by Peter Handke. Reviews of the film often say, “based on the novel by” but actually the screenplay came first so, I suppose, the novella—way too short to be called a novel—is a novelisation only it’s not really. Both have lives of their own but as Handke has worked continually since the mid-sixties there’s a great danger that a slight work like this might get lost under the mountain of books that followed it. That said, The Goalie's Anxiety at the Penalty Kick has managed to keep its head above water and become a fixture in many school curricula. The German version of The Left-Handed Woman (Die linkshändige Frau) was published in 1976; the film followed in 1978 along with an English translation so it’s easy to see why people might assume the film was an adaptation of the book. But why write the book?

I rewrote the film script in the form of a narrative for the following reasons: after several books in which “he thought” “he felt”, “he perceived” introduced many sentences, I wanted to make full use of a prose form in which the thinking and the feeling of the figures would not be described, where, therefore, instead of “she was afraid”, we would have “she went”, “she looked out of the window”, “she lay down next to the bed of the child”, etc. And I perceived that this kind of limitation with regard to my literary work was liberating. – Handke quoted in June Schlueter, The Plays and Novels of Peter Handke, p.154.

So, essentially, an experimental novella then and, as we all know, experiments can go badly wrong and yet so many artists insist on doing this: typing, dancing or painting with one hand tied behind their back. Sad to say the novel was not received as enthusiastically as the film.

Ultimately one might argue that the inadequacy of this particular novel follows from just these austere limits which Handke chooses to impose on his language – for it seeks to convey an imagistic order which, by definition, can never really be made apparent in the novel and which, as a function of the work’s conception, has preceded it. – Timothy Corrigan, Film and Literature: An Introduction and Reader, p.261 quoted in Martin Brady and Joanne Leal, Wim Wenders and Peter Handke: Collaboration, Adaptation, Recomposition, p.237

Or as Leal and Brady put it, “an arresting presence in the film can only remain an absence in the text.”

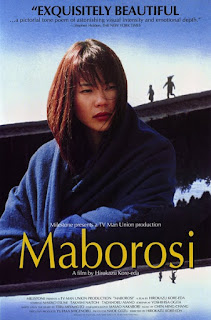

The film eschews dialogue but you can get away with that—the silent filmmakers did for years—and filmgoers cope (a good modern example would be the Japanese film Maborosi); readers aren’t always as resilient or patient. The director of Maborosi is Hirokazu Koreeda whose work is often compared to Yasujirō Ozu. I mention this purely because in the film version of The Left-Handed Woman the woman takes her son to see Tokyo Story; in the novella it’s simply “an animated cartoon”.At the centre of Handke's work (be it prose or film) stands a specular subject: "Seeing is being for Handke's protagonists." Looking, watching, observing, are their primary occupations; hence, they position themselves almost in such a way they can look on as spectators or pure outsiders. – Gerd Gemünden, Framed Visions, p.146

There is an autobiographical element to the book but what I found interesting (particularly since I do it myself in my novel Left) is that he chooses a woman as his protagonist. The book, an exploration of loneliness (at least on one level), was written after his first wife, the actress Libgart Schwarz, left him which was shortly after his mother committed suicide. Two losses; one straight after the other. It’s no great surprise then that a book like this might have been the result but actually there were two; the 1972 novella A Sorrow Beyond Dreams is based on his mother’s life. Handke, as he mentions in his play The Art of Asking, “writes out of his wound” and yet this is a surprisingly… numb book. Or maybe not so surprisingly.

The book has an omniscient narrator who tells it as he sees it but only what he sees:

She was thirty and lived in a terraced bungalow colony on the south slope of a low mountain range in western Germany, just above the fumes of a big city. She had brown hair and grey eyes, which sometimes lit up even when she wasn’t looking at anyone, without her face changing in any other way. […] The woman was married to the sales manager of the local branch of a porcelain concern well known throughout Europe; a business trip had taken him to Scandinavia for several weeks, and he was expected back that evening. Though not rich, the family was comfortably well off, with no need to think of money. Their bungalow was rented, since the husband could be transferred at any moment.

When her husband returns we learn her name is Marianne but the narrator insists on using “the woman”; likewise “the child”, even when his mother calls him Stefan. “The publisher”, “the shop girl”, “the chauffeur”, “the actor”, “the father” (i.e. the woman’s father)—the narrator keeps everyone at a distance apart from Bruno—he always calls Marianne’s husband “Bruno” (with the single exception in the quote above)—and Franziska, a close friend of the couple and also the boy’s teacher although once Stefan calls her “the teacher”—“Bruno wants to come over with the teacher”—and she objects—“I have a name. So stop referring to me as ‘the teacher,’ the way you did on the telephone just now.”

The first thing that struck me about the relationship of the husband and wife was her subservience:

The woman came from the kitchen, carrying a silver tray with a glass of vodka on it, but by then there was no one in the living room.

I’ve seen plenty of TV shows where a husband comes home after a hard day’s work and his wife hands him his favourite tipple but she never presents it on a tray no matter how well off they are. Servants, yes, absolutely, but not wives. Up until then he just seemed like a very, very tired man. He hugs his wife when they meet (once she’s relieved him of his luggage), talks about his trip—“Those northerners may not eat very well, but at least they eat off our china”—and tells his wife he missed her and then says something I found a little odd:

I thought of you often up there, of you and Stefan. For the first time in all the years since we’ve been together, I had the feeling that we belonged to each other. Suddenly I was afraid of going mad with loneliness, mad in a cruelly painful way that no one had ever experienced before. I’ve often told you I loved you, but now for the first time I feel that we’re bound to each other. Till death do us part. And the strange part of it is that I now feel I could exist without you.

She doesn’t reciprocate or respond. Her sole reaction is to change the subject.

The next thing that annoyed me about Bruno was this:

My ears are still buzzing from the plane. Let’s go to the hotel in town for a festive dinner. It’s too private here for my taste right now. Too—haunted. I would like you to wear your low-cut dress.

He doesn’t tell her, he doesn’t order her, but he doesn’t leave it up to her. They end up spending the night at the hotel. On the way home the woman has what she describes as “an illumination”:

“I don’t want to talk about it. Let’s go home now, Bruno. Quickly. I have to drive Stefan to school.”

Bruno stopped her. “Woe if you don’t tell me.”

The woman: “Woe to you if I do tell you.”

Even as she spoke, she couldn’t help laughing at the strange word they had used. The long look they exchanged was mocking at first, then nervous and frightened, and finally resigned.

Bruno: “All right. Out with it.”

The woman: “I suddenly had an illumination”—another word she had to laugh at—“that you were going away, that you were leaving me. Yes, that’s it. Go away, Bruno. Leave me.”

After a while Bruno nodded slowly, raised his arms in a gesture of helplessness, and asked, “For good?”

The woman: “I don’t know. All I know is that you’ll go away and leave me.” They stood silent.

Bruno smiled and said, “Well, right now I’ll go back to the hotel and get myself a cup of hot coffee. And this afternoon I’ll come and take my things.”

There was no malice in the woman’s answer—only thoughtful concern. “I’m sure you can move in with Franziska for the first few days. Her teacher friend has gone away.”

Bruno: “I’ll think about it over my coffee.” He went back to the hotel.

And so they part. Just like that. No histrionics. No tears. No debate. Nothing. Bruno moves in with the teacher and no one seems that surprised or troubled. It’s all excruciatingly… civilised, a pre-emptive strike. We’re all going to die anyway so let’s just kill ourselves and get it out the road. There’s some sense to a sentence like that; death is unavoidable and it would be nice if we could meet it on our own terms but divorce is not inevitable. The statistics are not encouraging but plenty of marriages do stay the course.

She’s not the only one to have an “illumination”. In order to support herself the woman contacts the publishing house where she used to work to ask for some translation work; apparently her boss had been keen not to lose touch. He brings the manuscript he wants her to work on personally. An excuse to test the water—flowers and champagne were a bit much—but it comes to nothing and he doesn’t push it. As he’s about to leave though he tells the woman this story:

Not long ago I broke with a girl I loved. The way it happened was so strange that I’d like to tell you about it. We were riding in a taxi at night. I had my arm around her, and we were both looking out the same side. Everything was fine. Oh yes, you have to know that she was very young—no more than twenty—and I was very fond of her. For the barest moment, just in passing, I saw a man on the sidewalk. I couldn’t make out his features, the street was too dark. I only saw that he was rather young. And suddenly it flashed through my mind that the sight of that man outside would force the girl beside me to realize what an old wreck was holding her close, and that she must be filled with revulsion. The thought came as such a shock that I took my arm away. I saw her home, but at the door of her house I told her I never wanted to see her again. I bellowed at her. I said I was sick of her, it was all over between us, she should get out of my sight. And I walked off. I’m certain she still doesn’t know why I left her. That young man on the sidewalk probably didn’t mean a thing to her. I doubt if she even noticed him…

It is not that different to what happened with the woman and her husband only in Marianne’s case the other woman is purely imaginary.

From then on we follow the woman day by day as she comes to terms with her decision. Bruno pays lip service to the idea of reconciliation but that’s about it. Perhaps he saw it coming. Perhaps, although he wouldn’t have been the one to suggest it first, he’s glad she did or at least a part of him is.

Her publisher isn’t the only one to chance his arm. At a photo booth the woman runs into an unemployed actor. Some days later she encounters him again in a café; he says he recognised her car in the parking lot and came looking for her:

I’ve never followed a woman before. I’ve been looking for you for days. Your face is so gentle—as though you never forgot that we’re all going to die. Forgive me if I’ve said something stupid. […] Damn it, the second I say something I want to take it back! I’ve longed for you so these last few days that I couldn’t keep still. Please don’t be angry. You seem so free, you have a kind of”—he laughed—“of lifeline in your face! I burn for you, everything in me is aflame with desire for you. Perhaps you think I’m overwrought from being out of work so long? But don’t speak. You must come with me. Don’t leave me alone. I want you. Don’t you feel that we’ve been lost up to now? At a streetcar stop I saw these words on a wall: ‘HE loves you. HE will save you.’ Instantly I thought of you. HE won’t save us; no, WE will save each other. I want to be all around you, sense your presence everywhere; I want my hand to feel the warmth rising from you even before I touch you. Don’t laugh. Oh, how I desire you. I want to be with you right this minute, entirely and forever!

She fails to respond. Now watch how Handke handles what follows:

They sat motionless, face to face. He looked almost angry; then he ran out of the café. The woman sat among the other people, without moving.

A brightly lighted bus came driving through the night, empty except for a few old women, passed slowly around a traffic circle, then vanished into the darkness, its strap handles swaying.

This is poetry. In fact in an interview with June Schlueter in 1979 Handke talked about his books as “epic poetry” rather than novels. We don’t get to hear her thoughts. We have to make do with what she does and where she looks and use our imaginations.

So people come and go. They have their say and/or make their play but at the end of the book the woman is still alone:

Standing at the hall mirror, she brushed her hair. She looked into her eyes and said, “You haven’t given yourself away. And no one will ever humiliate you again.”

It is no great surprise to read that women—and not only feminists—appreciate this more that many of Handke’s other novels.

The title of the book isn’t obvious. There’s no indication given whether the woman is left- or right-handed although in the film the actress is right-handed. The title comes from a song the woman plays over and over again but not the one by The Statler Brothers (Johnny Cash’s original backing band), John Hartford or Jimmy Reed. The first verse goes:

She came with others out of a Subway exit,

She ate with others in a snack bar,

She sat with others in a Laundromat,

But once I saw her alone, reading the papers

Posted on the wall of a newsstand.

It’s an odd song mostly listing off unexceptional day-to-day things like leaving a building or sitting on the edge of a playground and these are exactly the kind of things we watch the woman do. One of the lines goes, “For there at last I shall see you alone among others,” and then later in the novel we read, “In the morning the woman, among others, walked about the pedestrian zone of the small town.” Her life is far from exciting but in an article entitled Forms of Identity: Stations of the Cross in Peter Handkeʼs Die linkshändige Frau Scott Abbott makes a few noteworthy observations about the structure of the book. (A version with the quotes translated into English can be found here.) Whether deliberate or not the book contains a great many nods to the life of Christ from the “discarded Christmas trees” to her telling her son about seeing “some pictures by an American painter”:

There were fourteen of them. They were supposed to be the Stations of the Cross—you know, Jesus sweating blood on the Mount of Olives, being scourged, and so on. But these paintings were only black-and-white shapes—a white background and crisscrossing black stripes. The next-to-last station—where Jesus is taken down from the cross—was almost all black, and the last one, where Jesus is laid in the tomb, was all white. And now the strange part of it: I passed slowly in front of the pictures, and when I stopped to look at the last one, the one that was all white, I suddenly saw a wavering afterimage of the almost black one; it lasted only a few moments and then there was only the white.

In the article Abbott identifies these as Barnett Newman's Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachtani. An odd thing for an author to have his protagonist talk to a young boy about unless there was a point to it. It’s not as if Handke is an especially religious man despite (or, perhaps, because of) his upbringing; he refers to himself as »religiös geschädigter Internatsmensch«, a religiously damaged person as best I can guess at a translation. Abbott makes a stab at his reasoning:

Handke’s story exploits the Christian Stations of the Cross not out of a sense for Christ’s divinity, but because that narrative form is part of our cultural vocabulary, because those words exist, because that is a useful language game (and that is exactly what this is, a Wittgensteinian language game) we are used to playing. […] These are the religious forms of Die linkshändige Frau, the Christian structures that, emptied of metaphysical content, can suggest dialectical possibilities as Marianne reconstitutes her life.

In a blog entry he describes Handke as “aesthetically religious, not spiritually religious”. I can buy that. It was why Beckett co-opted religious imagery into his texts, because it was familiar, to him first and foremost, but also he expected it to be familiar to his prospective readers. The simple fact is The Left-Handed Woman is nowhere near as simple as it first appears which is why it’s great that it’s so short because it won’t take long to reread.

Why left-handed though? Oral traditions worldwide associate left-handedness with evil. There’s nothing to suggest the woman is evil so what then? In John Hartford’s song he describes a contrary person:

Left handed womanUp until the sixties children were coerced into right-handedness but it was more to do with standardisation than anything else. It's much easier to teach children (especially writing) if everyone in the class is the same. The book itself isn’t especially helpful. In fact the only thing the woman says that might give us some clue is this:

You south pawed member

Of the female gender

Tender bender of

My splendour

Look at you

You do everything backwards

You inside out, upside down

Left handed woman you

What I can’t bear in this house is the way I have to turn corners to go from one room to another: always at right angles and always to the left. I don’t know why it puts me in such a bad humour. It really torments me.

The climax of the book—I use the term loosely—takes place one evening when all the major players, and a couple of the minor ones, gather at the woman’s house for, as the Kirkus Review put it so well at the time, “a veritable orgy of meaningful exchanges and gestures. But Marianne remains alone.” Not exactly a last supper—not enough people for starters—but something of a final trial, a gauntlet to be run. Sort of.

This book appears at #317 on 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die. It’s not why I read it. I picked up half a dozen books and this was the first one where I got past the first page. Simple as that. I can see why some people don’t like it. I can see why others love it. Everyone’s been alone at some time or other but how many of us would choose it? One reviewer on Amazon (who gave the book 4 stars) said, “This book will appeal to connoisseurs of claustrophobia and angst.” They’re not wrong but if I wanted to be reductive I’d say, “This book will appeal to all those who’ve looked at someone and wondered, What the hell is going on inside your head? and had to make up an answer for themselves.”

I’ll leave you with the trailer for the film.