I wanted to show you what was happening here. Because anybody who sees it and can carry on with his life as if nothing’s the matter belongs before a firing squad. – Chris Barnard, Bundu

Biafra was the first I remember. We told jokes about starving Biafrans in the playground. We should’ve known better. Then there was Ethiopia, then Ethiopia again, Somalia, the Sudan, Ethiopia once more, the Congo, Zimbabwe, Sudan again, Malawi, Niger, the Horn of Africa. And these were just the newsworthy ones. The sad fact is there’s hardly been a year since the 1970s when thousands of Africans haven’t been starving. I was often starving in the 1970s. I’d rush home from school and dive into the biscuit cupboard and tell my mum I was starving but, of course, I wasn’t starving; I probably wasn’t even especially hungry. All my life people have been appealing to us for aid and bit by bit compassion fatigue’s set in. Images of little black babies with bloated bellies don’t shock us like they used to or ought to but they’re still not attractive images so when I learned that Chris Barnard’s novel Bundu focused on an African famine I didn’t find myself exactly desperate to read it; what fresh could he possibly have to say?

Bundu is not a new novel. It was first published in 1999 in Afrikaans and has only now been translated into English; other reviewers have commented on the quality of the translation but I can only take their word for it. The book centres on an isolated clinic somewhere on the South Africa-Mozambique border whose settlement starts to become the destination for a number of refugees, the Chopi, not the thousands we see on the TV, just a couple of hundred, but the doctor and nurses are simply not equipped to deal with even that number; this was not what they signed up for; they’re not aid workers. As I started to read about them the first thing I found myself thinking of was Northern Exposure of all things. It’s a certain kind of individual who moves into an isolated setting like that; they usually have pasts they want to be as far away from as possible and that’s exactly the kind of people we have here; damaged individuals who now have to cope with people even more damaged than themselves. But let’s not be too quick to pity the Chopis:

That the Chopis had waited until halfway through the third summer of drought before crossing the border was proof of their extraordinary endurance.

We don’t learn a great deal about them which I thought was a pity. I would’ve liked to see them as more than just ‘the refugees’ but maybe that was done deliberately because these are people who are not only dislocated but disenfranchised and deculturalised; we don’t see them hauling their musical instruments with them—their music was proclaimed a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2005—all that has been abandoned.

Our narrator is Brand de la Rey, a wildlife researcher who applied for the position because it put him as far away from civilisation as possible; no one else wanted the job anyway. He’s not a complete misanthrope though and there are a few fellow eccentrics whose company he can tolerate like Julia Krige, the local nurse who he’s developed a soft spot for (and it is reciprocated) but neither is in a rush to do anything about it; neither has been lucky in love before so why should this be anything different? The blunt fact is that no one can afford to be completely alone in such an inhospitable place. None of the natives could be described as loquacious and even when they did talk often what they said was cryptic and no amount of pressing would get them to say more than they felt needed to be said; Strydom, the archaeologist, talked in half-sentences and avoided addressing people directly (“the addiction to first names probably figured to him as an excessive show of brotherliness”), Tito de Gaspri, who delivered de la Rey’s each month, never gave a straight answer to a question and Bruyns, one of the Red Cross doctors, “was not a man for detail. He supplied only the most essential of facts.” None of them are much into talking about their pasts.

You couldn’t really describe the structure to this book as a crucible but it does have that kind of feel to it. When Hitchcock was populating his lifeboat or O'Bannon deciding on the crew of the Nostromo I’m sure they spent a long time figuring out what the perfect mix of people would be. Getting the balance is important. We do get to learn the backstories of most of the characters—Julia was a nun before she turned to nursing, Mills was a musician before he became an alcoholic pilot, presumably Strydom has a first name once upon a time—but now they’re all pretty much alike and, like the baboons that circle de la Rey’s house, keep everyone at arm’s length.

You couldn’t really describe the structure to this book as a crucible but it does have that kind of feel to it. When Hitchcock was populating his lifeboat or O'Bannon deciding on the crew of the Nostromo I’m sure they spent a long time figuring out what the perfect mix of people would be. Getting the balance is important. We do get to learn the backstories of most of the characters—Julia was a nun before she turned to nursing, Mills was a musician before he became an alcoholic pilot, presumably Strydom has a first name once upon a time—but now they’re all pretty much alike and, like the baboons that circle de la Rey’s house, keep everyone at arm’s length.

There’s no antagonist in this book—unless you count bureaucrats, the military and Mother Nature—and everyone takes their turn playing the hero; either that or there are no heroes and it’s just a bunch of people doing the best they can in impossible circumstances. Surprisingly the refugees fade very much into the background despite the fact the book’s focus is How are we going to save as many of these as we can? A couple stand out, a woman with red beads and a child who insists on bringing Julia feathers but mostly they remain nameless, faceless and voiceless. We learn more about the baboons but I wonder if that’s not deliberate. The monkeys are also starving. There’s been no rain for a very long time and the vegetation is quickly disappearing. The humans can be kept alive by slaughtering the odd animal—an injured hippo early on in the book is a real find—but what can one do for a troop of baboons? Two scenes in the book are worth contrasting. The first involving the humans from the beginning of the book:

[Julia] was making her way towards a woman lying in a patch of shade just outside the shelter. There was a baby in the woman’s arms about three months old and reed-thin. The child was dead still and every now and again the woman tried with jerky movements to drive the flies from its face. I stood looking, stirring the pot, at Julia patiently trying to get some soup into the child’s mouth with a piece of reed.

[…]

The child vomited up the few scraps of soup in his throat—there, take it, it’s too late—and closed his eyes. The woman on the ground stretched out her arms to the child as if she wanted him back. But Julia put him down on the ground, because he was dead.

This second one comes near the end:

There was a strange sound among them which we couldn’t quite make out. It was a very soft tapping sound as if one of them was walking on a badly made wooden leg. We watched them more closely to see if we could trace the origin of the sound. After a while Vusi pointed out one of the larger females. She had something in her hand, a scrap of sack or cloth. As long as she could get by on three legs, we could hear her walk—but as soon as she had to use the other front paw and couldn’t move the cloth to another foot in time, something inside the cloth—something like a dry wild orange or calabash—struck the rock. […] For a second it lay there on the rock in front of me before she could grab it and take off with it. It was the dry head and scrap of hide and tail of what earlier in the summer would have been her offspring—only the nostrils and eye sockets recognizable in the little skull rattling in the desiccated scalp when she stepped on the wrong front paw.

Both are equally tragic and yet it was the latter that had the greater impact on me. I’ve thought about this for a couple of days now and I think the difference between the two mothers boils down to language; the human can be comforted with words, can bury her child and start the grieving process; we think of most Africans as primitives and yet she’s civilised enough to realise there are appropriate ways to deal with the death of a child. The baboon, however, does what the human might want to—not let go.

Thankfully the book is careful not to overpower us with too many images like this; it would be an unbearable read if it did. It focuses instead on the lives (and loves) of the foreigners. Essentially though there’s no difference between the humans and the baboons other than the fact the humans live in hope of being rescued; all the baboons can wait for is rain or death. A few pages after the last quote de la Rey returns to the clinic and makes this observation:

“This poor…” I couldn’t find a word for the little flock that above us in the three stuffy little wards was lying waiting for the night. They were no longer people; they weren’t just matter either; they were not dead and no longer really living. “These poor… wretches.” That was the only word I could find.

Okay, so we know what the problem is. What’s the solution? Phone calls are made daily. Long stories. Reasons. Excuses. Apologies. And every day, thanks to the efficiency of the bush telegraph, more arrive than are dying. Time is against them. The answer comes in the unlikely shape of Jock Mills who, we learn, has been rebuilding a Dakota DC-3 in the middle of the jungle pretty much for the hell of it; it had been abandoned by the army, gutted by the natives but the superstructure, engine and electrics were still mostly intact. And so the next film to jump into my head had to be The Flight of the Phoenix, the 1965 original, of course. It’s not quite that bad—the DC-3 from all accounts is now actually airworthy. At least that’s what de le Rey is told when he first broaches the subject with Mills; Mills’ airworthiness is another matter entirely but he’s certainly up for the job. The fact that the plane can only carry about sixty means three or four trips and that’s asking a lot of both plane and pilot.

Okay, so we know what the problem is. What’s the solution? Phone calls are made daily. Long stories. Reasons. Excuses. Apologies. And every day, thanks to the efficiency of the bush telegraph, more arrive than are dying. Time is against them. The answer comes in the unlikely shape of Jock Mills who, we learn, has been rebuilding a Dakota DC-3 in the middle of the jungle pretty much for the hell of it; it had been abandoned by the army, gutted by the natives but the superstructure, engine and electrics were still mostly intact. And so the next film to jump into my head had to be The Flight of the Phoenix, the 1965 original, of course. It’s not quite that bad—the DC-3 from all accounts is now actually airworthy. At least that’s what de le Rey is told when he first broaches the subject with Mills; Mills’ airworthiness is another matter entirely but he’s certainly up for the job. The fact that the plane can only carry about sixty means three or four trips and that’s asking a lot of both plane and pilot.

First things first, let’s see if he can get the damn thing off the ground. That proves easier than probably either of the men expected it to be but as de la Rey sees the plane rise into the air he notices that one of the landing wheels doesn’t look right. This initial flight was supposed to last fifteen minutes but an hour passes, and then two. No sign of Mills and with no radio no way to find out what’s happened. Have their plans been scuppered? Well, it wouldn’t be much of a book if they had but no one is going to make life easy for this small group despite the worthiness of their cause. Mills had noticed the wheel too and realising that it would be foolhardy—if not downright suicidal—trying to land in the jungle, had headed immediately for the nearest runway he thought he had a chance of landing safely on. This turns out to be Manzini in Swaziland. Of course as soon as he touched down they arrested him. After some interrogating and wrangling his story is confirmed and one Jenny Grobler appears on the scene. As usual with this lot we don’t get to learn much about her or her relationship to Mills, not at first anyway (bits are filled in later), but despite, to quote de la Rey himself, being “not particularly pretty”, “dressing like a man and behaving like a man” and insisting on calling him “Mr Brand”—and even years later (which is when this book is written) looking back—he finds himself unable to explain why “she had such a paralysing grip on [him] almost instantaneously.” But, of course, this does toss the spanner into the works with regard to his feelings for Julia.

How though, at a time like that, can people worry about stuff like love and sex? Because when you don’t have a roof over your head, a blanket to wrap round your shoulders or a mouthful of food to keep you going you find comfort where you can. Some people are never more alive than when they’re dying, never more aware of being alive. It’s really no different from those convicts who find God five minutes after they’ve been locked up in prison only to forget about him the second they walk through the gates to freedom.

I’m not going to say how the book ends. Nothing goes to plan but that would’ve been too easy. Barnard has done some screenwriting in his day—his script for Paljas was the first South African film to be nominated for an Oscar—and he clearly knows that we need a moment or two of crisis in the middle to keep our interest (the ‘boy loses girl’ bit or in this case ‘boy loses plane’). The basic plot structure here is not especially exciting—Barnard’s doing nothing new here essentially—but I found once I got over that I started to appreciate the under and overtones. I can easily see this being adapted for the small (or big) screen where (probably) all that will be lost.

In her short review of the book, Karen Rutter says:

[T]here’s the odd tendency to “Over-Africa” the novel. You know, when writers start pulling “dark continent” clichés out the bag – fiery sunsets, starving children with flies in their eyes and superstitious natives.

I’m not sure I agree with her and it’s a sorry world where starving children have become a cliché. Okay there were a few words I would’ve liked to have had explained, bundu, for starters:

bundu [bʊndʊ]

n

(Sociology) South African and Zimbabweanslang

a. a largely uninhabited wild region far from towns

b. (as modifier) a bundu hat

[from a Bantu language]

but mostly you could get the idea from the context: stoep [veranda], kloof [ravine], kraal [cattle enclosure], veld [outback], donga [an eroded ravine; a dry watercourse], vlei [an area of low marshy ground, especially one that feeds a stream]. I can’t pretend not being familiar with these words wasn’t a little annoying but it’s not like there were hundreds of them. A number were clearly the names of common plants like the calabash mentioned in one of the earlier quotes which is a gourd… whatever a gourd is.

This book could’ve gone in several different directions. It avoids being preachy but it makes its points well enough. What I particularly liked was the ending. Circumstances have galvanised these disparate individuals, created a necessary bond but once the crisis is over—their involvement in it at any rate—they no longer have sufficient reason to cohere and drift apart far too easily. You would think what they’ve been through was a life-changing experience but perhaps these people’s lives had already been so changed by what had happened in their pasts that nothing was ever going to bring them back. It certainly made me pause for thought because, at least as far as Africa goes, nothing has changed there. A few people manage to get saved but who’s to say that where they ended up will not face its own famine in two or three years? All part of what de la Rey calls “the Great Process”, not a Divine Plan but an admission that “Nature had no use for chance”.

You can read a lengthy extract from Bunduhere.

***

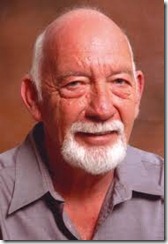

Chris Barnard was born in Nelspruit in 1939. His full name is Christiaan Johan Barnard but I can see no connection with the famous South African heart surgeon, nor, if it comes to that, the infamous South African executioner. He matriculated in 1957 and completed a BA degree in 1960 at the University of Pretoria. He worked as a journalist for seventeen years and as a script writer and film producer between 1978 and 1994. Barnard has published thirty books, including novels, plays for stage and radio, short stories, film scripts and children’s books. In February 2012, he was recipient of the Department of Arts and Culture’s South African Literary Awards (SALA) for lifetime achievement.

Chris Barnard was born in Nelspruit in 1939. His full name is Christiaan Johan Barnard but I can see no connection with the famous South African heart surgeon, nor, if it comes to that, the infamous South African executioner. He matriculated in 1957 and completed a BA degree in 1960 at the University of Pretoria. He worked as a journalist for seventeen years and as a script writer and film producer between 1978 and 1994. Barnard has published thirty books, including novels, plays for stage and radio, short stories, film scripts and children’s books. In February 2012, he was recipient of the Department of Arts and Culture’s South African Literary Awards (SALA) for lifetime achievement.