My friend Hubert Selby Jr., or “Cubby,” as his friends called him, used to get upset when I’d mention “hope” in talking to him.

He always said that once you had a concept, you had its opposite. That you couldn’t have up without down, left without right, right without wrong, hope without hopelessness. – Michael Lally, ‘Selby and Hope’, Lally’s Alley, 15 June 2007

As of today—by the time this gets posted this will likely have changed—there are 1757 books people have seen fit to include in Goodreads’ list of The Most Disturbing Book Ever Written. Topping the list currently, and with a healthy lead, is American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis. The Bible comes in at #8 (and, again, at #108) which made me smile. Hubert Selby Jr’s first entry is a sorry #59 for Requiem for a Dream, Last Exit to Brooklyn staggers home at #91, I had to scroll all the way down to #143 to find The Room—a mere twenty-five people voted for it—and The Demon drags its heels at #197. The poor rankings can be indicative of two things: 1) Selby is nowhere near as disturbing as you might’ve heard and/or 2) he’s nowhere near as well read as the likes of Ellis… and, well, God.

The Room was published in 1971 but we’ve moved on since then and what disturbed and offended us back then—Ken Russell’sThe Devils and William Peter Blatty’s novel The Exorcist appeared the same year —we find tame by comparison to even what’s on television these days. It’s subjective, of course, and what upsets one others will shrug off. Over three hundred people voted for The Handmaid’s Tale in Goodreads’ poll and I really can’t see, certainly by comparison to Selby’s oeuvre, what anyone has to complain about. But, as I’ve said, what upsets one…

Whether The Room is the most disturbing book ever written is a moot point and as more books get churned out other pretenders will step forth. What I can say is I found it hard going and it definitely is the most disturbing book I’ve ever read; I can’t think of anything that comes close. This, perhaps, says more about my choice of books than anything else.

In a short entry in Spike Magazine from 2005 the author (whose name I couldn’t pin down) writes:

The Room is possibly the most powerful novel I’ve ever read, insofar as its physical impact upon me—absolute nausea and fear and dread. I write this without any hint of hyperbole—the book made me physically sick throughout reading it and has remained in my consciousness in the 15 years since: not because it is so revolting but because it utterly captures the essence of desperation and self-loathing at the core of the human condition. I know I make it sound melodramatic, but it’s not. It is such a horrific book because you can sense the truth in every sentence. It’s not written to shock. It’s written as an exploration of the imagination and the interior self that involves no self-censorship.

[…]

I certainly don’t think I could face reading The Room again. Being 17 when I read it, I didn’t know literature could do that. Now I do know, I don’t think I want to go back there again.

In an interview with Bill Langenheim which appeared in Enclitic 10 in 1988 Selby himself said, “The Room was the most disturbing book I have ever read. I mean, it is really a disturbing book, Jesus Christ! I didn't read it for twelve years after I wrote it.”

The Room, let’s be clear, is not a horror novel although there are two or three horror novels called The Room and it’s easy to see the potential. Actually none of the books with high votes in Goodreads’ list were conventional horror novels. The Room also appears (and quite rightly so) in another of Goodreads’ lists; it’s #57 in the Unconventional, Seductive, Intelligent and Dizzyingly Surreal category. It’s often cited as an early example of transgressive fiction but as soon as you try to categorise a book you hem it in. It’s like looking up a list of symptoms on the Internet; there are so many things you could have and probably don’t. Suffice to say if you appreciate Selby’s writing style then there will be other novels that get labelled “transgressive” such as Naked Lunch, A Clockwork Orange and Trainspotting that might appeal although as far as I’m concerned they’re tame compared to The Room. My question would be: Once you’ve read The Room why would you want to read another book like it?

When I first picked up the novel, purely because I’d read two other books called The Room and it amused me to look for another, I didn’t read much about it beforehand and that was probably a good thing. I knew of Last Exit to Brooklyn and I’d seen the film adaptation of Requiem for a Dreamso I had some idea what I was in for but I still imagined it might have more in common with Knut Hamsun’s Hunger than anything else. At least that was what I was hoping for. It would’ve been too much to expect anything remotely Beckettian; he loves putting men in confined spaces and watching them torment themselves (think Eh Joe or Malone Dies). Later, after finishing it and preparing to write this article, I discovered that Selby himself had called the book “Kafkaesque” which had I read that beforehand I would’ve taken with a pinch of salt but, for once, it actually is.

The genesis of the novel is easy enough to trace—Selby knew exactly what it feels like to be locked up in a prison cell (he was arrested for driving under the influence)—but I would advise against assuming this is in any way autobiographical. Like the rest of us he’s drawn on his observations and experiences and then allowed his imagination to do its stuff. I’m sure he would’ve agreed wholeheartedly with Barthes (who argued that writing and creator are unrelated) and has said as much. In the documentary It/ll Be Better Tomorrow, he puts it quite bluntly: “The writer has no right to be there in the work. I don’t have any right to impose myself between the people I’m creating on that page and the reader. […] The responsibility of the artist is to transcend the human ego.”

Selby first tackled the subject of a man alone in a cell in ‘The Sound’ (which you can find in his short story collection Song of the Silent Snow) and Swans’ frontman Michael Gira summaries the story quite nicely in an interview from Silencerin 1997:

It's a prisoner in a room –who's insane, it appears. He's alone, doesn't know how he got there or where he is. It's just a white room, and a door with a hole in it. He starts to realise he hears this sound that's moving closer and closer and closer outside. And finally he can't take any more, he gets up, he's terrified, he looks out the window. And it doesn't even say what he sees, but you think that he sees his own face. It's like this terror of existence, basically.

As the story unfolds we discover who the man is (he’s called Mr. Rawls by a staff member) and where he is (the County Jail Hospital); we also learn that he’s been arrested before and is somewhat reassured when he realises this. It’s not a lot but it makes all the difference. In The Room we’re left guessing. The nameless man may be insane—or, at least, deranged—but it’s never confirmed. He may be guilty or he may be innocent but even if he is we’re never told what he’s been charged with. We do know he’s an adult but for the longest time I didn’t even know if he was black or white and that does make a difference. Is he even a bad man? What exactly is a bad man come to think of it? The only physical description there is is that he has a spot—which may or may not be a pimple—on his cheek.

In an interview with John O’Brien for The Review of Contemporary Fiction O’Brien asks Selby why he doesn’t describe the man in the room. His answer:

Why physically describe him? It’s completely immaterial. What he looks like is unimportant. Description would be necessary only if he were ugly or had a scar on his face that caused him to be the way he was. But such is not the case. I’m not concerned with the outside. I think that Gil [Sorrentino] said that one of the reasons that critics don’t want anything to do with me is because I don’t give them any handles like that to grab hold of and with which they can feel safe.

I like the expression he uses, “handles … to grab hold of” because anything he might reveal about him distances him from his readers. Simply the fact that he’s a man removes him one step from all the women out there. He’s meant to be as close to an everyman as possible which is why, for example, Selby never made him a novelist or a political prisoner. From the same interview:

I could have made him a novelist or a political prisoner, you’re right. I’d be a millionaire today. I’d get the Nobel award if I had made him a political prisoner in Russia. But the world isn’t made up of these extraordinary people; the world is made up of little people like us.

I think he’s on the right track because I found myself scrambling as I read this book to distance myself from its protagonist. I felt like I was trapped in the 9 x 6 room with him and I did not want to be there. Whatever I could grab on to I did. And the main thing was he was American. That kept him at arm’s length. He grew up in the shadow of the American Dream. Thankfully there’s no British equivalent but that doesn’t mean we don’t have our own problems.

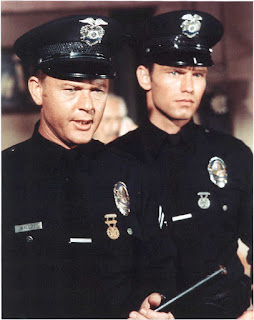

There were police where I grew up. They weren’t exactly neighbourhood bobbies but they weren’t a presence either; it was unusual to see a copper. Not like I imagine—that imagination fired by a lifetime’s worth of American TV shows and films—it was like living in Brooklyn in the middle of the twentieth century even if historically Brooklyn (where Selby grew up) has had lower crime rates compared to the likes of the Bronx and Manhattan. The man in the room relives various encounters with policemen throughout his life and it almost feels as if it’s the same two guys checking in on him to see if it’s his time:

Just see how they dog your every step just waiting for you to commit some sort of infraction of the law. yeah, the bastards.

One of the first encounters—he’s eight years old at the time—goes as follows:

Son … son (2 huge blue giants stood behind her. Couldnt see the doorway. They were up to the ceiling. Couldnt put his head back far enough to see their faces. Just a doorway filled with blue. And mommy standing in front. Why is she gonna let them take me away? He/d never see her again. never). Son. The police officers want to talk to you about the dog that bit you yesterday …

Sure enough, yesterday he’d been bitten on the heel by a dog. His mother had comforted him and then taken him to the doctor who cauterised the wound but who said he’d have to report it. After a good night’s sleep the boy’s forgotten all about it. Being a wee boy he’d probably forgotten what the doctor said as he was saying it. He did not expect two policemen to come a-calling:

They want to know where [the dog] lives. She entered his room and sat beside him and held his hand. The doorway widened and he could see their faces. (its only about the dog. they werent after him.) The cops and his mother talked with him for a few minutes and assured him that they wouldnt hurt the lady that owned the dog, they only wanted to test the dog.

So he has to go with them. In the squad car. But there’s a problem:

Then a jolt of panic almost made him bolt from the moving car. Suppose they searched him. Suppose they found it. They might send him to jail. They might tell his mother. How could he get rid of it. If he tried to sneak it out of his pocket they might see him. And if he did get it out what would he do with it. They kept talking to him. Telling him not to worry. Must be something wrong with the way he looked. Cant let them know. Maybe they do know. Maybe they saw it when they came downstairs. Maybe theyre not going to the dogs house. Its only half a block.

What does he have in his pocket? A knife? Drugs? No, it’s a slingshot. And he gets away with it.

They had me cold, the dumb cops, but I got away. Wow!

I’m sure dozens, hundreds of kids could tell similar stories blown out of all proportion by their imaginations. Because that’s the thing about cops. They’re the good guys—they’re not hoodlums or pimps or anything—but they’re not all that good. No one’s all good. And, even at a tender age, he would likely have been aware of the concept of the dirty cop. Later on, following a shooting three blocks away, another two policemen (or maybe the same pair) arrive at his house looking for guns but all they find is his Tom Mix cap pistol.

If you found yourself locked in a cell on your own with nothing to do but think what would you think about? You’d think about what you did—or what people are accusing you of—the thing that’s got you locked up and you’d think about you’re going to get out but there’s something about being in a jail cell: guilty or not you feel guilty and all have us have stuff to feel guilty about. We might not have committed criminal offences but that doesn’t mean we don’t have things we don’t want to come to light. In his interview with Selby O’Brien wonders about the things he has the man remember from his childhood—which are mostly early sexual fumbling and let’s face it sex and guilt have a long history—and asks:

I’ve tried to find a relationship in The Room between the character’s past and present, but I cannot find one. What I am looking for are the causes for his present condition. Yet, he seems to have had nothing horrible happen to him; his mother loved him, he had a girlfriend, and so on.

This is a particularly relevant question because, at the start of their conversation, Selby opens with:

I feel that my books thus far, including the one I just finished, Requiem for a Dream, are pathological in the sense that they are looking at the disease, they are trying to examine the disease. Usually any cure or treatment for a disease starts with the pathologist isolating it, trying to find its nature, so that others can do something to make this condition better. So, I am looking at the disease. And the disease, as you see it in all my books, is the lack of love.

So I was puzzled too but as Selby explains later:

The things that haunt him are guilt, the things he created guilt over. He wet his pants or something. I remember that the obvious implication was sexual guilt, which he made into a religious, authoritative kind of thing.

Put a guilty man in a cell—it doesn’t matter whether he’s guilty of the particular crime he’s been charged with or not—and that guilt will start to bubble up to the surface. He has a lifetime’s worth of memories to draw on but the ones he’s drawn to are ones that encourage him to feel bad about himself. Selby tells O’Brien:

We all cause everything that happens to us, whether we recognize it or not. That's a cosmic law, which I also know from my own experience. I know from my own experience that when I send out hate, my life is filled with hate. There's only one source of energy for my hate and that's me. And there's only one ultimate destination for my hate and that's me.

Why is the man incarcerated? Because he’s a bad man. Bad men get locked up—the cops must’ve seen something in him that he couldn’t see himself—ergo he is a bad man. And what do bad men seek? Redemption perhaps but that’s a problem if you find yourself caught in a Hubert Selby novel. What I found interesting is a short passage where the man in the cell’s talking about playing cops and robbers or cowboys and Indians as a kid:

[E]very day, before the game started everyone yelled Im a bad guy–Im a good guy, and, somehow, in a matter of seconds there were two sides and they were running, riding and shooting.

It’s almost arbitrary who gets to be a good guy or a bad guy. There needs to be the right number of good guys and bad guys and so Life or Fate or God makes sure there are. It’s only a game after all, a word that crops up again and again in the novel: “I/ll beat them at their own game”, “They cant play their games with me”, “Play a new game: hunt a fucking cop”.

In her blog Jasmine Angelique Hemery includes the following which appears to be a quote from Selby but I’ve been unable to find out from where:

What happens in my work is there is no catharsis [...] it's just such intense suffering and darkness that the reader finds within themselves the ability to love the unlovable and I... I didn't figure out that oh this is what I'm going to do—of course not—but if that's the result I think it's absolutely wonderful and magnificent... I mean if I can do that I can't think of a greater goal to work for and towards … than to help another human being find out that the light they're seeking is just within them and it's always there.

Selby tells Ellen Burstyn (who plays Sara Goldfarb in the film adaptation of Requiem for a Dream):

[T]he first four books are pathological without any catharsis, any relief, any answer. But what has happened is something very very amazing, I think. During these years I’ve talked with thousands of people, or gotten letters, and there is one thing, one word that everyone uses with reference to my work, and that’s “compassion.” And they found within themselves the compassion and ability to not judge the people that ordinarily they would judge into the grave. Suddenly they have compassion for these people. Which is extraordinary. That’s not what I set out to do, but evidently that’s the result, because I hear that from so many people. So the first four books are an attempt to really look at the darkness in as many different ways as I could. Then I wanted to not only go from the darkness to the light, but to show how you get from the darkness to the light. You see I’ve never wanted to just tell a story. I wanted to put the reader through an emotional experience. And I believe the reason for that is that I’ve always been a frustrated teacher and a frustrated preacher.

In his later books we see a very different Selby, one more interested in solutions. But you have to work through a problem to get to its solution and what we have here are some very messy workings.

The Room opens with the following short paragraph:

Defence counsel touched the defendants hand before slowly rising and facing the jury. He hesitated only a second before speaking. I do not ask for justice for the defendant, but mercy.

It does make it sound as if his client is guilty of committing some crime and, of course, the burden lies on the prosecution to provide convincing evidence but the more I got through this book—and certainly by its end—I found myself wondering where exactly this scene fits into the proceedings. On the second page we find a man in a cell. It’s night but he can’t sleep. He made the mistake of napping that afternoon but he’s philosophical about it:

Well, anyway, time has to pass. But sometimes its so goddamn long. Sometimes it just seems to drag and drag and weigh a ton. And hang on you like a monkey. Like its going to suck the blood out of you. Or squeeze your guts out. And sometimes it flies. Just flies. And is gone somewhere, somehow, before you know it was even here. As if time is only here to make you miserable. Thats the only reason for time. To squeeze you. Crush you. To tie you up in knots and make you fucking miserable. If only you could sleep 12 or 16 hours a day. Yeah, that would be great. It doesnt happen though. Maybe you can do it for one day. If you go a few days with only a little sleep. But after that youre right back where you started from. Trying to sleep so the goddamn time will pass.

Selby, as you can see, uses unconventional grammar and punctuation. There are no apostrophes. When confusion might arise—e.g. Ill and ill—he uses a slash: I/ll. He doesn’t use speech quotes and often skimps on capital letters. Plus, occasionally, he uses idiosyncratic spellings—krist instead of Christ. Compared to reading A Clockwork Orange, however, it’s a cakewalk. Selby’s reasoning? In an article in The Guardianin which he explains how a near-death experience became the inspiration for his junkie parable Requiem for a Dream he writes:

I write, in part, by ear. I hear, as well as feel and see, what I am writing. I have always been enamoured with the music of the speech in New York.

The man in the cell’s mind starts wandering and he begins to imagine a scenario where he manages to smuggle out a letter—written on toilet paper with the stub of a pencil he has to sharpen with his teeth—and this letter finds its way into the hands of Mr Donald Preston, publisher of the Press, and Mr Stacey Lowry, world-renowned criminal lawyer. Next thing you know his door clangs open and he’s told he has visitors, Mr Preston and Mr Lowry, who promise to get him out which they do and they have big plans for him. Preston tells him:

Well, Stacey and I have discussed that very thing and we were certain, after reading your letter, that you were the individual we have been looking for to assist us.

You see, we want to mount an all-out campaign, using your experience as a springboard. I – we – believe, with you in the foreground, that the results will be both beneficial and efficacious.

Within no time our unnamed man finds himself before Congress:

He stretched out on the bed, let his eyes close and listened to the chairman of the special investigating committee of the Senate of the United States.

On behalf of the other members of this committee, and myself, I want to thank you gentlemen for appearing before us and making available to us, and the citizens of our country, evidence of misuse and abuse of authority. And especially to you, sir, who did so while your life was threatened. […] You have set a fearless example and it is now up to us, and the Congress of the United States, to follow your example.

It’s all fantasy. In reality he’s been assigned a public defender called Smith:

Public defender. What the hell does he care. Probably trying to get a job in the d.a./s office anyway. All they want you to do is plead guilty. Yeah, they tell you if youre not guilty say so. But they do everything they can to get you to plead guilty. Public defender. ha. Defender. My ass defender. Couldnt even defend that, the rotten a.k./s. Afraid to bug the judge because they might get in front of him when they have a private practice. Just trying to make friends with every son of a bitch in court except their client. Client? Aint that a crock of shit. Just another bum to them. Dont even want to sit too close to you. Youre just a springboard to a jr. partnership anyway. A deaf mute could do a better job

All the eloquence his fantasy self displayed has gone. What we do learn is that this is just a preliminary hearing which means he’s being held on remand. There is hope. Which means there is also hopelessness.

He wiles away the time thinking about the past, escapades as a kid and early sexual encounters before he really knew what he was doing. Like many kids he hated school:

Fuckit. Who gives a shit. The dried-up old douche bags. Why in the hell do they teach school if they hate kids so much. Stop that giggling. Dont you know youre disrupting the class. Shit. They just cant stand to see people laugh. They got their rules and a sour face and thats it. They dont want to know anything. If you dont do it their way theyll screw you up.

The two cops keep cropping up though:

He was 12, or maybe 13. He and 2 friends were shooting crap under a light in the park. It was a cool evening and they were completely involved in the game and in keeping their hands warm. There was 2¢ on the ground and he was shooting for a point. As he was reaching for the dice someone yelled, cop, and they ran. He grabbed for the 2¢ and before he could get up and start running a cop came out of the bushes behind him and hit him across the reaching hand with his club. He ran, never knowing what the cop looked like. Not even feeling the pain until an hour later. The cop didnt pursue them and a block away he met his friends and they walked the few blocks home together. They asked him about his hand. He said it was all right, but it was starting to burn. When he had been home in the warmth of the house for a while, the pain started to increase. He was afraid to tell his parents as they would want to know why he had been hit and he was afraid to tell them what he had been doing. In the middle of the night the pain became acute. He moaned in his sleep and his mother came into his room to wake him and ask what was wrong. He told her he had fallen while playing a game and had hurt his hand. Early the next morning they went to the hospital and the hand was x-rayed. Three bones were so sharply broken it looked like a razor cut. He had been hit so hard there wasn’t a trace of splintering. The break didnt even need to be set or put in a cast. It was that clean a break. A small roll of gauze was put in his palm and the hand was wrapped. It was that simple.

Eventually he turns his thoughts to the two officers who arrested him and starts to imagine all sorts of things about them. Firstly he relives the scene of his arrest only this time he goes on the offensive:

When the officer pulled his gun – first he warned them he was a karate expert – he hit him on the wrist, the gun falling, and jabbed his finger tips in the others adams apple. He then shoved his finger tips in the first ones solar plexus, chopped the second on the back of the neck and did the same to the first one. They fell unconscious to the ground and he disarmed them. He then went to the pay phone on the corner and called the newspaper and related the events that had just occurred and requested that a reporter be sent to the scene. Not many minutes later a reporter and cameraman arrived and they called the authorities. In the few minutes before three squad cars arrived he quickly repeated his story to the reporter while the cameraman took many pictures.

Then he imagines torturing the cops who begin to morph into dogs:

A couple of lumps with their tongues hanging out and spit dripping down their chins. And maybe put a dog collar around their throats and lead them with a leash. Yeah, after all, theyll need some exercise. Have to keep them away from trees and fire hydrants though. Yeah, on a fucking leash. With their fucking badges stuck through the tips of their noses. And their fucking wives can greet them with open arms. Here children, say hello to your father. This is daddy. Woof, woof. O, what a nice daddy you have. Comeon.

He continues to abuse the dogs “training” them:

Now beg you sonsabitches. No. No. Not like that. He stood back and looked at them for a moment, shook his head then flogged them and prodded them in the balls with the cattle prods. Keep your hind fucking feet flat on the floor. Now bend your knees. No. No. For krists sake. He shoved the cattle prods up their asses and kept them there for many long, painful seconds. Keep them at a 45-degree angle. Goddamn stupid mutts. He shoved the prods up their asses and flogged them, then stopped and surveyed the scene for a moment, thinking. I guess youll just have to learn the hard way.

This goes on for page after page. He even forces them to have sex with each other so, of course, one of them has to play the bitch. It’s crude, vulgar and nothing is left to the imagination.

Later he pictures the cops as men again and with names, Fred and Harry, stopping a woman just like they’d stopped him:

What did we get this time Fred? A living doll Harry. 5,5, a hundred and 25 lbs, and all tits and ass. How old is she? What the fucks the difference. Shes a good piece of ass. They laughed. I/ll drive her car and you follow.

They don’t arrest her. Instead they take her to “a place in the hills” and repeatedly rape her. These are—or at least have become in our prisoner’s mind—dirty cops and so it’s not a huge stretch of the imagination to imagine them having a bit of fun only this is no bit of fun. Recently there was a lot of fuss about the ten minute rape scene in Irreversible—I actually discovered the clip on a site devoted to rape scenes from mainstream films (you’ll notice I’m not providing you with a link)—but I can assure you it’s tame compared to what you’ll find described here. And the thing is it just goes on and on and on. Selby could’ve covered the rape scene in two or three paragraphs and let his readers use their imaginations but he doesn’t. The woman ends up in hospital and not just to recover from her assault:

At the time we visited her she had been there almost a year and was still too hysterical to talk without heavy sedation. Up to that time she had had over one hundred shock treatments with no permanent results. She would be all right for a few weeks or so, but then she would gradually get worse and they would have to put her in restraint and eventually more shock treatments were necessary. As of last Thursday, the last time we contacted the hospital, the prognosis was the same … no hope. According to the doctors she will spend the remainder of her life in the institution, and most of that time she will be hopelessly insane.

The man then drifts back to his courtroom fantasy only this time he’s become his own counsel and he has the two cops on the stand. He casts them as idiots and easily tricks them into revealing they were the ones who assaulted Mrs Haagstromm. It’s all very Perry Mason. They wind up in an asylum and he ends up having sex with both their wives.

Then he returns to his fantasy about the dogs in which, in front of an audience, he pits them against a starving rat who does not go down without a fight. Back and forth, back and forth, he jumps between fantasies and memories and the reality of his situation. Several times the guards let him out—“Chow time”—but he makes no effort to interact with any of his fellow inmates and only wants to get back to the safety of the cell. Sometimes he barely eats. He just wants to get back to his fantasies:

[H]e hoped he didnt get out too soon. It would be a good idea if he stayed there a while. It would add more power to his story. He was glad he didnt simply bail himself out immediately. It was much better this way. He would stay here as long as necessary and endure all the hardships and privations necessary to help him accomplish what he had to. And they would pay many times over for what they did to him. For every second of misery spent in this hellhole he would see to it that they spent a year in hell. A living hell. They would suffer torment and anguish so deep they would plead for mercy. They would beg him to let them die. O no. They werent going to die. Not yet, the fucking bastards. They had to suffer. When those fucking cops go home and tell their wives they got kicked off the force and all the newspapers and magazines and television networks carry the story and their pictures theyll wish to krist they were dead. When their kids go to school and all the other kids point at them and laugh, and their kids come home crying, I hope they think of me. I hope they never forget that Im the one that did it. I hope they live a long, long time and spend every minute of every day hoping to die and remembering me. Me, you rotten pricks. Dont ever forget me because Im never going to forget you.

Eventually he wears himself out. Finally the spot comes to a head. It’s a fairly obvious metaphor but it serves its purpose. And then the door clangs open one last time and a “set of blues [is] tossed on his bed. A voice [yells] court time.”

In an article he wrote for The Guardian in 2003 Selby has this to say:

The man in The Room poisons his entire being with obsessive thinking, unaware that he is the only victim of his obsession. He has so victimised himself that when they open the door to freedom, he is unable to leave his cell.

He’s going back to court. This time it’s for real. This time he’ll only have Smith to defend him. He might get off with it—he might even be innocent—but it’s all left hanging. It doesn’t really matter. What he’ll be free from is not knowing. At least that’s how I read it. But what about us? What do we do with all we now know, with what we’ve not simply witnessed but experienced with the characters? In an interview with James Sullivan for SFGate (SF as in San Francisco not science fiction) Sullivan asks Selby, “Was there some measure of redemption you felt for those people, that their tragic stories were getting told?” His answer, in part:

Reading the books is so overwhelming that the reader is forced to find that catharsis within themselves. And they find themselves having compassion for somebody who under all circumstances they would have condemned. So in that sense, redemption, perhaps. I don't know.

Talking to O’Brien Selby said, “We all cause everything that happens to us, whether we recognize it or not. That's a cosmic law, which I also know from my own experience. I know from my own experience that when I send out hate, my life is filled with hate. There's only one source of energy for my hate and that's me. And there's only one ultimate destination for my hate and that's me.” Later O’Brien asks him, “Then your characters ‘get what they deserve’?” to which Selby responds:

What they deserve in the sense of “What ye sow, so shall ye reap,” Sure. They not only planted the seeds, they watered them. They took very good care of them. Sure, deserved in that sense. Not necessarily in a moral sense, but in a sense of justice. In a sense of inevitability. There are balances in life that you just can’t avoid. Sooner or later it happens, it always does.

This is where I struggled with The Room because I couldn’t see what fuelled the man’s rage. We learn, for example, that when he was fifteen he “had run away from home again” but why “again”? What was he running from? Or trying to escape to? We don’t know. The two cops appear again and this time he does end up spending a night in the cells. He has a loving mother and, although his father is only mentioned briefly, his dad seems all right too. The day he comes home after Leslie—Leslie’s a girl—pees on him he gets shouted at, made to take a bath, sent to bed early and told to stay away from her but that’s it. His father doesn’t flay him within an inch of his life so clearly there’s more going on here than we’re privy to. Selby describes his own father in an interview with Rob Couteau as, “Violent, drunk, maniacal,” but, again, we need to be careful not to mix up Selby with his creation. In that respect his approach is quintessentially Beckettian as Beckett consistently refused to have intimate exchanges about the motivations of his stage characters, about what happened to them in the past (any more than he reveals in the text) or about their emotional states.

I had hoped through reading interviews and articles about Selby I might come to some level of understanding—where did this book come from?—but the more I learned the more confused I got. He talks often about the rage that filled him as a young man but looking at him in later life you’d be tempted to call him a sweet old man and he clearly was a man many people were genuinely fond of. He ends the SFGate interview by saying, “There was just so much fury in me that I was unaware of it. I went through life like a scream looking for a mouth.” That fits with my first impression of the man who wrote The Room and then he bowls me a googly—or whatever the American equivalent of that might be—in what he says in a letter to James Giles (reprinted in Giles’s book Understanding Hubert Selby, Jr.):

By the time I started THE ROOM I was in love with God. . . . Perhaps it was that love that gave me the courage to write it. . . .

Also, I have to believe a few things about what I thought was my hatred for God. Its [sic] simply the old love/hate relationship. I loved this thing called God so much, hungered for it more than anything in the world, yet felt I was undeserving of Its Love, so I raged at it. Ive [sic] also come to believe that the hatred helped keep me alive. It literally energized me. The Latin word from which we get our word, violent, means, Life Force, and I guess that was the only way I could animate that Life Force at that time; i.e, prior to accepting the fact that I Loved this thing called God.

This is a far cry from the young man portrayed in Ghetto Images in Twentieth-Century American Literature: Writing Apartheid:

Selby was born to Hubert Sr. and Adalin Selby in 1928. In 1944, he left high school and his Bay Ridge neighbourhood and enlisted in the Merchant Marines. Two years later, while aboard a ship near Bremen, Germany, Selby fell violently ill from contact with tubercular cattle. What saved his haemorrhaging body was his mother’s acquisition of streptomycin, then still an experimental drug. The doses administered to him were too large, however, impairing his hearing and vision and damaging his muscle function. Selby spent much of the years 1946 and 1950 within the operating room, enduring at least ten procedures that removed one-and-a-half of his lungs and ten ribs. Once youthful, athletic and seaworthy, Selby was now a spleen-filled invalid cursing the heavens. “I was enraged at everything,” Selby recalls, “and to the best of my ability, I directed all my rage and anger toward God because that was the son of a bitch who did this to me.”

In the documentary, It/ll Be Better Tomorrow, Michael Silverblatt characterised Selby’s writings—and not merely his later works—as “spiritual guidebooks for the sick” which, on the surface, seems not only generous but also a bit romantic. There is no denying the fact that the more you read about Selby the more words like “spirituality” and “epiphany” keep sneaking their way into the conversation; even the man in The Room experiences an epiphany when he realises his only friend is his loneliness. To that end you should read his conversation with Rob Couteau entitled

‘Defining the Sacred: Author Hubert Selby on Spirituality, the Creative Will’ and Michael Lally’s blog post ‘Spirituality (& Hubert Selby Jr.)’.

The style of The Room takes a bit of getting used to. At first it feels like it’s going to be a straightforward third person narrative but the next thing you know you’re in the man’s head and then out and then in again without any warning. Selby told Couteau:

It’s all inside this guy’s head, like in The Room. There’s no narrator, but there is a commentator that kind of pops up, every now and then. Sometimes he seems to be the devil, and sometimes he seems to be Jesus. I don’t know who he is. He just pops in and out. And makes comments about things.

The first example I can think of that’s in any way similar to this is Little Britain because that’s very much what Tom Baker does. A better, although less well known, example would be Geoffrey Rush’s voice over in the Australian sitcom Lowdown. It sounds like it would be hard work to follow but you do get used to it surprisingly quickly. As Selby tells O’Brien:

[I]f you wanted to analyse it carefully, you can tell quite easily what’s fact and what’s fantasy, what’s first and what’s third person. You can see that the language changes. You can tell what’s fantasy and what’s actually memory by checking the rhythms of the line and the language.

It is a remarkably musical work. As he said, to Allan Vorda:

You have a theme of the prisoner's reality which includes such variations as his memory of it and his projections. You might call it an enigma variation.

A little less Elgar perhaps and a lot more Beethoven. Again, to O’Brien:

Those repetitions are musical in nature. I use them in various ways—words, phrases, or various rhythms. So the reader isn’t necessarily aware that there are repetitions, but emotionally he’ll react. Emotionally he will bring back something from twenty pages before.

[…]

My only conscious influence as a writer is Beethoven. There is nothing more obvious than his Fifth Symphony and its obviousness attains subtleties that go on ad infinitum. That’s my ultimate goal in writing. As I say, you don’t have to read it, it comes off the page, it surrounds you.

The Book has not been filmed. I don’t think it’s unfilmable but it wouldn’t be easy viewing especially if the director was faithful to the material. More people will see Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange than will ever read the book but despite the “ultraviolence” in the film it’s still a toned-down version of what Burgess wrote. For example, in the novel Alex (who’s fifteen) rapes two ten-year-old girls but in the film we get to see a teenage Alex having consensual sex with two girls not much younger than he is. But that was in 1971—now there’s a coincidence—and God alone knows what they’d show if they remade it for today’s audience.

Should you read this book? I would say, yes, but for the right reasons. In most cases I would argue that a work should stand or fall on its own merits—and I still believe that—but in cases like this I do think it’s helpful to know something about the author and his reasons for writing the kind of book he’s written. The important thing to remember is no one was injured in the writing of this book: no boys were bitten by dogs; no dogs were beaten by men; no rats were torn apart by dogs; no women were raped or shot; no wives cheated on; many will, however, have been arrested during that time and some of them without cause and it is to those, in part at least, the book is dedicated:

with love,

to the thousands

who remain nameless

and know.

Further reading / viewing / listening

Memories, Dreams and Addictions

It/ll Be Better Tomorrow

Bookworm (part one)(part two)

Defining the Sacred: Author Hubert Selby on Spirituality, the Creative Will, and Love

All Kinds of Hell... Hubert Selby, Jr. meets Kirk Lake

A Conversation with Hubert Selby By John O’Brien

Q & A / Hubert Selby Jr. / Going deep into the dark side