[T]the line between fiction and confession was so fine it didn’t exist – Andrew McCallum Crawford, ‘When Iron Turns To Rust’

Just over a year ago I reviewed Andrew McCallum Crawford’s first collection of short stories, The Next Stop is Croy and other stories. As in that collection the characters in A Man’s Hands often appear in more than one story and although these stories stand on their own (and, indeed, have been published as standalone pieces) they do form part of a larger story arc and are enhanced because of this. That said, the Jacks, Johns, Andys, Matts and Seans all feel a bit like they all ought to be Andrews. I asked him about this and he said he thought I’d hit the nail on the head here:

Perhaps they all are Andrews. More precisely, perhaps they are all Andrew. Perhaps. The title of the collection is A Man's Hands, not Men's Hands.

When I read this the first time—at 60 pages it’s not exactly a long read—I didn’t pay too much attention to who the protagonists were in each of the stories. There was ‘the man’ and ‘the woman’ and that was as much as I really needed to know and I did find myself mixing them up. This has been something I’ve complained about before where there has been a cast of thousands—okay, a dozen or so—but never where most of the stories only contain two players. The fact is the names really are pretty much irrelevant and only serve to remind the readers which stories are (officially) linked. I add the proviso because, as I will explain, I think all the stories here are thematically interlinked.

The first thing I had to do when I’d finished the book was to go back and get the story threads straight in my head. There are eleven stories broken down into six sections:

SEAN

The Canny Cyclist

MATT

Gimlet

JACK

Edinburgh Arrivals

Arthur’s Seat

Edinburgh Departures

JOHN

Sofitel Gatwick

Player

ANDY

Chicken Soup

Gentlemen, We Have A Winner

When Iron Turns To Rust

CLIO

A Man’s Hands

The longest single story, taking up about a third of the book, is the first one. It reminded me of Harold Pinter, specifically his play The Homecoming. Writing in The New Yorker, the critic John Lahr had this to say about the play:

The Homecoming changed my life. Before the play, I thought words were just vessels of meaning; after it, I saw them as weapons of defence. Before, I thought theatre was about the spoken; after, I understood the eloquence of the unspoken. The position of a chair, the length of a pause, the choice of a gesture, I realized, could convey volumes. […] The Homecoming offered no explanations, no theory, no truths, no through line, no certainties of any kind.

The play explores the nature of family. In brief: after having lived in the United States for several years, Teddy brings his wife, Ruth, home for the first time to meet his working-class family in North London and, of course, she is in danger of being the outsider. That’s not how Pinter plays his hand but I’m not here to talk about Pinter other than to get you thinking about the mood he generates in his best-known work.

Pinter was not a conscious influence however. Andrew says:

I am aware of Pinter's work, although I am not an aficionado. I have only ever seen one of his plays—The Collection—in Thessaloniki way back in 1991. I remember being struck by the things you mention. Having said that, I wouldn't cite Pinter as an influence. The four greats for me are Malamud, Kelman, Donleavy and, of course, Carver. Of these four, I would say that it is Malamud and Carver who have influenced my writing (meaning the way I write) the most.

Conscious or not this was what I saw/brought to these stories.

In Sean’s story, after only a couple of dates (if you include their initial meeting at a party in Edinburgh) Sean takes the train down to York to be with his girlfriend, Rose, a Geordie whose father’s a Dundonian so goodness knows what they’re all doing in York; we learn that Sean’s an east-coaster which is to be expected since Andrew hails from Grangemouth and, as I’ve said, all the male protagonists in the book feel like his proxies. We learn very little about Rose: she has long eyelashes, is prone to pouting, isn’t embarrassed by public shows of affection, is a newly qualified teacher, can drive, drinks Earl Grey tea, likes chocolate éclairs (the cake, not the sweets) and toast but not sausages and hasn’t seen her family in a while. We learn even less about Sean: he likes public shows of affection, owns an overcoat, is the kind of guy who’d buy his girlfriend a red, family-sized toaster on their second proper date and can play a bit of piano. So, if, like me, you’re not a huge fan of description and exposition then Andrew’s the bloke for you.

After a day out sightseeing they go back to her flat where Rose gets a phone call. The phone’s in the hall and so Sean doesn’t overhear anything; besides he’s busy watching the telly.

She was gone a while. When she came back in, she sat in the armchair on the other side of the room. She had crumbs at the sides of her mouth. ‘Fancy a drive?’ she said.

‘Eh?’ said Sean. ‘Where?’

‘I need to go home,’ she said. ‘It’s been a while. I’ve been putting it off. You’re welcome to come with me if you want.’

This was a surprise. ‘Of course I’ll come with you,’ said Sean. ‘I’d like that.’

No explanation is offered nor is any sought. It’s a fair drive from York to Newcastle (about 75 miles) during which one might’ve imagined Sean would ask questions about her family (I certainly would) but, no, the only eventful thing about the car journey is the fact that the left—and shortly thereafter—both windscreen wipers give up the ghost. This may strike you as odd especially if you’re a writer because we tend to be nosey besoms, but there are people out there who, even if they are curious, hold themselves back from prying and this is a characteristic of many Scots and northerners. So Sean finds himself in her parents’ house very much the outsider.

After a while Kevin, the titular cyclist, appears and the two men do not hit it off. So who’s Kevin?

‘He’s an old friend,’ said Rose. ‘We were at school together. He’s a bit clingy.’ She examined her nails. ‘But he’s been...never mind. He’s not important.’ She smiled, but he could see it was forced. ‘You’re not jealous, are you?’

Words. All you could do was listen to them. ‘Should I be?’ he said.

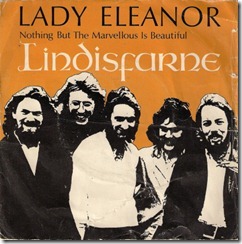

So, we missed out on the phone conversation, we miss out on whatever the ellipsis is hiding and later that evening when her drunken dad turns up and sticks a CD on repeat playing the same track over and over again (‘Lady Eleanor’ by Lindisfarne) Sean misses out on his lovemaking; she’s still up for it—‘It’s what [Dad] does. Don’t worry, he won’t come up here.’—but Sean’s too distracted to perform. The man’s drunk, blootered in fact—he looks like he might have been injured in a fall or a fight—and Rose gets him to bed before crawling into her own. Sean tries to talk to her but, predictably, she’s not up for it: ‘Just go,’ she said. ‘It’s something...you would never understand.’

So, we missed out on the phone conversation, we miss out on whatever the ellipsis is hiding and later that evening when her drunken dad turns up and sticks a CD on repeat playing the same track over and over again (‘Lady Eleanor’ by Lindisfarne) Sean misses out on his lovemaking; she’s still up for it—‘It’s what [Dad] does. Don’t worry, he won’t come up here.’—but Sean’s too distracted to perform. The man’s drunk, blootered in fact—he looks like he might have been injured in a fall or a fight—and Rose gets him to bed before crawling into her own. Sean tries to talk to her but, predictably, she’s not up for it: ‘Just go,’ she said. ‘It’s something...you would never understand.’

In the morning good ol’ Kevin’s there—seems he’s found the time to fix the window wipers—and the two men get a chance to face off:

Sean leaned against the sink. He had forgotten to switch on the kettle. What am I doing? he thought. I’m bigger than this. ‘When did...how long’s her dad been...’

‘Didn’t she tell you?’ said Kevin.

‘No,’ said Sean.

‘No,’ said Kevin. ‘See, she’s like me. She’s canny. Come to think of it, she’s better than me. She knows not to talk to strangers.’

‘Okay,’ said Sean. ‘You broke it. Are you happy?’

‘Broke what?’ said Kevin. He bit into a crust and wiped crumbs from the corners of his mouth.

‘Don’t come it,’ said Sean. ‘You know what I’m talking about. I’ll be gone soon enough, don’t worry.’

‘That’s fine,’ said Kevin. ‘Champion.’ He got up and opened the door.

‘No, it’s not,’ said Sean. ‘It’s just the way it is.’ He heard him go into the living room, then their voices. He heard everything, but he was past caring.

Now, look at that scene as if it was a play and tell me you can’t see the Pinter in there:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By now you’re probably at screaming point, aren’t you? It’s like they’re talking in innuendoese. Why do these people have to say everything by not saying anything? Because that’s the way so many of these non-conversations go. By this time Sean’s sussed out a few things. He realises Rose’s mum’s dead which is why all her clothes are in the spare room. When was the funeral? That day? A week ago? A month? Presumably it was Kevin on the phone but just what’s the deal with him anyway and why did her dad, in his drunken stupor, assume he was Kevin? And how come Kevin painted everything white including the piano from all accounts? I can’t imagine. Don’t look at me for any answers because I don’t know much more than you and that’s all Andrew’s fault. Only I don’t see it as a fault.

Over on the Writer’s Digest site there are lots of friendly articles telling us what to do and not to do. In one of her articles Elizabeth Sims says, “resist the urge to over-explain … [your readers] can conjecture just fine” and in one of her articles Nancy Lamb writes, “allow [your readers] to intuit the meaning” of the text. There’s a great deal we never get to know about Rose and her family, even less than Sean because at least he got to hear her conversation with Kevin; we never do.

Jack’s story revolves around a slightly different male/female dynamic. In these three stories we have an older man and woman meeting up after many years apart. Really it’s hard to think of the first and last pieces as standalone pieces because they’re so short, a couple of bits of flash fiction really; they serve as effective bookends though. ‘Edinburgh Arrivals’ and ‘Edinburgh Departures’ are in the third person; ‘Arthur’s Seat’ is in the first person, Jack speaking. Although they’d like to think they know each other, after this many years—“half a lifetime”—they’re completely different people: “He had promised her the boy; she was confronted by a stranger.” So really the situation isn’t that dissimilar to ‘The Canny Cyclist’: there is an assumed familiarity that isn’t really there. Again there’s a difference—he’s a Scot, she’s now acquired a bit of an English twang. Non-Brits might not appreciate the significance of the UK’s north-south divide—we’re just one great big united kingdom after all—but the differences are many; to lose/give up ones accent is tantamount to losing one’s national identity. I don’t think Andrew’s making a political point here but I don’t think the decision to give Rose and Jill different accents can be considered as pure coincidence.

Touching is another issue these two men face, the desire to and the limitations of. When Sean is out with Rose at one point he squeezes her hand “but there was no response” and when Jill slips and Jack holds out his hand she chooses to grab his sleeve instead. The issue is one of control, i.e. power, another Pinteresque trope. Rather than visit the castle (just as Sean and Rose fail to visit the cathedral, the two biggest tourist attractions in Edinburgh and York) Jill suggests they walk up Arthur’s Seat which is an extinct volcano situated in the centre of the city of Edinburgh. Part way up, as I’ve said, she slips:

She grabs my sleeve. I feel the tug through the material. I want to touch her hand. I want to feel the skin of her hand in my hand. I want this woman, who was once my lover, to touch me. I want her to want to touch me. I want confirmation that I am still a man in her eyes, that I am still in the game. Back then, our relationship was defined by the word ‘control’. I couldn’t control her. I still can’t. I want something she won’t give, something she can’t give.

In Pinter's The Homecoming one of the important themes is power. Many of the characters try to exert power over others through various means such as sexuality and intelligence. You use the tools at hand. Information is power. Rose withholds it. Intimacy is power and although she’s open sexually their relationship still lacks intimacy; she refuses to confide in him. This is true of Jack and Jill and their hill and it was impossible to read this story without thinking of Scottish psychiatrist R D Laing’s book of poetry, Knots, which also feature Jack and Jill and their various power struggles.

In John’s story we have another similar encounter at an airport—this time it’s the Sofitel Hotel just by Gatwick Airport in London. There he meets an old lover and another power play ensues:

Slow down. You can control this. But these thoughts have a life.

She is standing in the space between the dressing table and the bed, looking for somewhere to sit. There is no need to sit down yet. He embraces her, but it is not supposed to be like this, embracing her ski jacket, embracing Gore-Tex and Velcro. It is her he wants to embrace, the essence of her. The smell of her perfume, but it is not her perfume.

A similar encounter takes place with Andy and his unnamed muse, another old lover. He has written a semiautobiographical work of fiction, a collection of short stories, one of which (which sounds exactly like the previous story in this collection, ‘Chicken Soup’) wins a major prize; a nice metafictive touch there. Much to his delight she turns up at the award ceremony in Plymouth sans husband and the opportunity—fuelled by nostalgia and alcohol—leads to the inevitable:

‘I want you to fuck me, Andy,’ she said. She sprang off the bed. The expression on her face. She wasn’t the girl he remembered. She was a woman. She pulled him upright by his belt. ‘Let’s see what you’ve got,’ she said.

Jump forward several months and into the next story. Andy’s dropped off the grid. In ‘When Iron Turns To Rust’ his muse turns up at his pathetic excuse for a flat a similar scene to the one involving John and Ailsa ensues:

He squared the sheet on the bed. He made it last longer than necessary, tucking the corners in just so. He could feel her standing behind him, next to the sink, taking in the state of the place.

The canister gave a final pop. The flame died.

‘I’d make you a coffee,’ he said. ‘But, eh...’

‘No, fine,’ she said. ‘I’m not...can I sit down?’ She wasn’t asking for permission. There were no chairs in the room. There was nothing in the room apart from the bed and the wardrobe.

Both could easily be stage sets.

Andy is a writer. But then so, it transpires, is John:

He wrote a book. It was a minor hit. Nothing major. It got a handful of good reviews. It dealt with a defining moment in his life. This defining moment had to do with things falling apart. It was a roman à clef [a novel about real life, overlaid with a façade of fiction], which was irrelevant in the great scheme of things, seeing as he was a nobody. A minor hit. The names, as they say, had been changed. He didn’t want to hurt anyone, he wasn’t that type of person. In any case, the names weren’t important, it was the facts, the event. He hadn’t written the book to examine other people’s motives. He had written it to understand the past, to understand how the past had affected the way his life had turned out

Unlike Andy, John doesn’t sleep with Ailsa in fact later on in the bar, in the next story ‘Player’, her husband, Michael, turns up and she leaves with him.

You can, perhaps, start to see how one could begin to get these characters mixed up.

The metaphor of tourism is a strong one and all the locations in the book—York, Newcastle, London, Edinburgh, Glasgow and London—are major tourist spots. In ‘Sofitel, Gatwick’ the woman looks out of the window and notes all the people. She projects sadness onto them. John suggests:

‘Maybe they’re tourists,’ he says. ‘People arriving somewhere. People at the start of something. Or on the verge of something. People like me.’

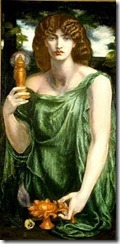

This ties in with the book’s dedication To Memory – the mother of the Muses. (In Greek mythology Mnemosyne (from which we get the word mnemonic) was the mother of the nine Muses by Zeus and was herself the goddess of memory and remembrance and the inventress of language and words.) Tourists are always out of place. How could we feel out of place in our own lives? By trying to visit or recreate the past as most of these characters try to do; the stage is still there but the players have moved on. John goes back to the college (Jordanhill if I’m not mistaken although it’s never named) where he first met his muse and ends up being ejected from the place by two cops who should IMHO get their own book. Just saying, Andrew.

This ties in with the book’s dedication To Memory – the mother of the Muses. (In Greek mythology Mnemosyne (from which we get the word mnemonic) was the mother of the nine Muses by Zeus and was herself the goddess of memory and remembrance and the inventress of language and words.) Tourists are always out of place. How could we feel out of place in our own lives? By trying to visit or recreate the past as most of these characters try to do; the stage is still there but the players have moved on. John goes back to the college (Jordanhill if I’m not mistaken although it’s never named) where he first met his muse and ends up being ejected from the place by two cops who should IMHO get their own book. Just saying, Andrew.

There are two other stories in the book, the second one, ‘Gimlet’ (a cocktail made of gin and I would imagine here in the UK Rose’s lime juice) where the protagonist is Matt and the titular story, ‘A Man’s Hands’ featuring the book’s only female protagonist, Clio. Matt shares a flat which is much like the one Andy ends up living in: “the only furniture was a mattress on the floor and a kitchen like a bombsite.” He doesn’t live alone. There’s Yanni (probably not the Greek pianist though) and Alan. She—whoever she is—has left him and he’s followed:

The facts didn’t need much working on. She came over here. You followed her. It didn’t work out. She left. You’re still here. What’s the point? There’s no point. What are you going to do? Stay here. You can’t go back there because you’ve been here too long. You’re a stranger here and a stranger there. In Limbo. You sleep most of the day and go out barring it every night. You drink. You drink. It’s got nothing to do with forgetting. Memories are sacred, no one can take them away from you.

Matt could be either Andy or John in that middle period, the bit Andrew doesn’t feel the need to tell us about, and, several years down the line if he’s ever bitten by the writing bug, he could easily turn into one of them. This is all conjecture on my part—I’m using my intuition—but that’s what I like about this book, I can do that; who’s to stop me?

Clio’s story felt, to my mind, out of place. At least on a first read. But it’s really not. Yes, Jack can play the piano as can Sean, and the man sitting across the table from Clio—the man with “the hands of a musician. A female pianist, perhaps. Not a man’s hands”—may well be one too; we never know for sure. Yes, we have a man and a woman across a table but this is a softer story. There’s not the same level of tension, no real conflict, no vying for control of the board. There is, however, a lot of hand holding. And a lot of trying to talk about the past. And then something odd happens:

Despite myself, I press into the soft flesh. Something happens. The part of your hands, the part of your hands that I am pressing, disappears. I look at your face, but all you do is talk. You continue to talk of the past, of things I don’t want to hear. I give all my attention to your hands. My fingers. I make small, circular movements which grow larger. Soon there is nothing left. Your hands have vanished.

[…]

I reach for your face. You continue to talk, you persist, even as I stroke your brow. Your forehead is gone. Then your eyes, that piercing blue is no more. I caress your cheeks and touch your neck.

I run a thumb across your mouth.

Silence at last.

You sit there, mute, faceless and handless. I think of the words tabula rasa,but this has nothing to do with the future. I have already forgotten what you look like, although I remember your hands, like a woman’s. Not a man’s hands.

This story is unlike any of the others. A man and a woman sit at a table and she literally erases him. No one notices this moment of magic realism. Who is she? His muse? His memories personified? (Clio was certainly the name of one of the nine Roman muses, the muse of history, and Mneme was one of the original three Boeotian muses, the muse of memory.) If a writer were to have a phobia which one do you think it might be? Atychiphobia: a fear of failure? Catagelophobia: a fear of being ridiculed. What about vacansopapurosophobia: the fear of the blank sheet of paper? Writing is cathartic. I have no doubt this book contains many biographical elements—Andrew went to Jordanhill College, he works in Greece, I’ll bet he can play a bit of piano (I never asked because it’s not important)—but, at the end, after all the words have been said (or written down) would it not be lovely if his muse would come along and wipe out everything he’s just freed himself from through the act of writing and left him with a clean, blank slate to begin again? It’s what happens. I’ve no doubt he’s written several stories since these and every one of them began with a lovely clean page or screen. That’s what I made of it. You might make something different.

This is a lovely collection. I enjoyed Andrew’s first book but this was, for me, a better read. These are spare, intelligent stories that don’t talk down to you; they demand you engage with them and complete them. When I was a wee boy my dad and I had a jigsaw puzzle of the Forth Road Bridge—I’m guessing five hundred pieces, my first proper jigsaw—which we built together. One morning I got up to find it finished and I was bitterly disappointed only it wasn’t finished. He’d left one piece to be slipped into place. It takes a lot of self-control to leave stuff out and to know what to leave out. I was lucky. Within me I seemed to have all the missing pieces to ‘finish’ this book. Others may struggle. That’s life not bad writing. I heartily recommend this book. At 17500 words it’s not a hard read but because it’s only sixty or seventy pages (depending on how you’ve got your e-reader set up) you might be more inclined to reread it. And you should. We don’t listen to songs only once and say, “What would I want to listen to that again for? I’ve heard it,” and the same logic applies every bit as much to writing; a measure of good writing is its capacity to be read more than once and continue to deliver.

The book is only available as an e-book from Amazon but for a couple of quid you really can’t complain. You can read the following short stories online:

***

Andrew McCallum Crawford grew up in Grangemouth, an industrial town in East Central Scotland. He studied Biology and Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh and went on to take a teaching qualification at Jordanhill College, Glasgow. He started writing when he was twenty and has been hard at it for twenty-four years now. His poetry and short fiction can be found on numerous sites online. His first novel, Drive!, was published in 2010. He lives in Greece where he works as a teacher.

Andrew McCallum Crawford grew up in Grangemouth, an industrial town in East Central Scotland. He studied Biology and Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh and went on to take a teaching qualification at Jordanhill College, Glasgow. He started writing when he was twenty and has been hard at it for twenty-four years now. His poetry and short fiction can be found on numerous sites online. His first novel, Drive!, was published in 2010. He lives in Greece where he works as a teacher.