The secret of happiness, you see, is not found in seeking more, but in developing the capacity to enjoy less. – Socrates

Be content with what you have; rejoice in the way things are. When you realise there is nothing lacking, the whole world belongs to you. – Lao Tzu

It is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor. – Seneca

Sell your possessions and give to the poor. – Jesus Christ

A Greek, a Chinese man, a Roman and a Jew over five hundred years apart all came to the same conclusion but Confuciusprobably says it best for me:“Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated.” A couple of hours ago Carrie and I watched, as is our wont of a Saturday lunchtime, the latest edition of Click,the BBC’s weekly news programme covering recent developments in the world of consumer technology and I wondered, as I often do when the programme comes to an end, how I am managing to survive with so few bits of technology in my life; why am I not utterly miserable?

[C]hildren born in the last decade and half [are] the first generation that has never known a world without hi-tech. These tweens and teens were born with dial-up internet, learnt to crawl alongside the PC and practiced writing the alphabet on the desktop. To them, a world without keypads, joysticks, digicams, headphones and LCD is unimaginable. For them, the Dark Ages are the time when television was black and white. – Happy Children’s Day, Mission 2020: Developed India

In 1975 I was sixteen and just about to leave school. The only tech I owned was an electronic calculator. I don’t even think I had a digital watch at the time. I look back at that time with a certain degree of nostalgia, I have to say. Life was simpler then. And yet at the same time my parents were looking back twenty-five years to the fifties and feeling nostalgic for that time. And, as we can see from the opening quotes which date back hundreds of years, people have always felt that life could be simpler than it is. In the fifties my parents were coming out of a period of great austerity, far worse than what we’re going though at the moment, and it was their generation that saw the rise of Consumerism in the sense we know it today; lives that revolve around, according to the OED, an "emphasis on or preoccupation with the acquisition of consumer goods." Things, for a time, really did seem as if they could make people happy: new fangled contraptions in the kitchen, flat-pack furniture, three television channels, fast cars, skimpy fashions and the end of rationing. It was a brave new world. But by the mid-seventies the lustre had gone a bit: in Britain a three-day week was imposed during February 1972 to save on electricity at the start of the miners’ strike; there was a recession from 1973 to 1975 and there was an oil crisis and a stock market crash. Novelist Tom Wolfe coined the term ‘Me decade’ in his article The "Me" Decade and the Third Great Awakening.

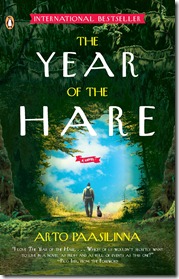

And while all this was happening, a thirty-three-year-old Laplander called Arto Paasilinna was having his own problems. He was working as a journalist at the time, which he found was growing "more superficial and meaningless" by the day and he was looking for a change. So, what did he do? He quit his job to write a novel. That novel, The Year of the Hare, became an overnight hit and has since been translated into twenty-five languages and has been made into a film, twice, a Finnish version in 1977 and an inferior 2006 French version. Since then Paasilinna has produced a book a year almost. His publishers say, "The annual Paasilinna is as much an element of the Finnish autumn as falling birch leaves." Now here’s the odd thing. I’d never heard of him, not even this, his most famous book. On top of that, The Year of the Hare wasn’t even available in English until 1995 and only then because it was included in 1994 in the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works which funded the English translation by Herbert Lomas. The first American edition only became available in 2010.

It is a timely release.

This is how the book opens:

Two harassed men were driving down a lane. The setting sun was hurting their eyes through the dusty windshield. It was midsummer, but the landscape on this sandy byroad was slipping past their weary eyes unnoticed; the beauty of the Finnish evening was lost on them both.

They were a journalist and a photographer, out on assignment: two dissatisfied, cynical men, approaching middle age. The hopes of their youth had not been realized, far from it. They were husbands, deceiving and deceived; stomach ulcers were on the way for both of them; and many other worries filled their days.

They’d just been arguing. Should they drive back to Helsinki or spend the night in Heinola? Now they weren’t speaking.

They drove through the lovely summer evening hunched, as self-absorbed as two mindless crustaceans, not even noticing how wretched their cantankerousness was. It was a stubborn, wearying drag of a journey.

On the crest of a hillock, an immature hare was trying its leaps in the middle of the road. Tipsy with summer, it perched on its hind legs, framed by the red sun.

The photographer, who was driving, saw the little creature, but his dull brain reacted too slowly: a dusty city shoe slammed hard on the brake, too late. The shocked animal leaped up in front of the car, there was a muffled thump as it hit the corner of the windshield, and it hurtled off into the forest.

“God! That was a hare,” the journalist said.

“Damn animal—good thing it didn’t bust the windshield.” The photographer pulled up and backed to the spot. The journalist got out and ran into the forest.

“Well, can you see anything?” the photographer called, listlessly. He had cranked down the window, but the engine was still running.

“What?” shouted the journalist.

The photographer lit a cigarette and drew on it, with eyes closed. He revived when the cigarette burned his fingers.

“Come on out! I can’t hang around here forever because of some stupid hare!”

The journalist went distractedly through the thinly treed forest, came to a small clearing, hopped a ditch, and looked hard at a patch of dark-green grass. He could see the young hare there in the grass.

Its left hind leg was broken. The cracked shin hung pitifully, too painful for the animal to run, though it saw a human being approaching.

This is very much how the Finnish film begins. The French adaptation decides we need to know a bit about the protagonist (who has now become the photographer by the way) and so we see him visiting a crime scene and being terribly moved by what he has to photograph. (What exactly he’s doing being allowed into a crime scene I have no idea – the version I managed to lay my hands on didn’t have subtitles.) I can see why they did this but to my mind it’s heavy-handed; it makes this man exceptional because how many of us have had access to the scene of a violent crime? The second paragraph of the novel tells us all we need to know. They could be a couple of insurance salesmen just as easily. And I think it is important that the protagonist of this novel be seen as an everyman because the less we know about him the easier it becomes to fill out his character with bits of our own. Ideally he’d be genderless but that’s asking too much of any author.

So what happens next?

The journalist picked up the young hare and held it in his arms. It was terrified. He snapped off a piece of twig and splinted its hind leg with strips torn from his handkerchief. The hare nestled its head between its little fore-paws, ears trembling with the thumping of its heartbeat.

In the meantime the driver who has been honking his horn in impatience decides, on a whim, perhaps, to teach the journalist a lesson; to drive off without him which he does.

The journalist put down the hare on the grass. For a moment he was afraid it would try to escape; but it huddled in the grass, and when he picked it up again, it showed no sign of fear at all.

“So here we are,” he said to the hare. “Left.”

That was the situation: he was sitting alone in the forest, in his jacket, on a summer evening. No disputing it—he’d been abandoned.

What does one usually do in such a situation? Perhaps he should have responded to the photographer’s shouts, he thought. Now maybe he ought to find his way back to the road, wait for the next car, hitch a ride, and think about getting to Heinola, or Helsinki, under his own steam.

The idea was immensely unappealing.

The journalist looked in his briefcase. There were a few banknotes, his press card, his health insurance card, a photograph of his wife, a few coins, a couple of condoms, a bunch of keys, an old May Day celebration badge. And also some pens, a notepad, a ring. The management had printed on the pad Kaarlo Vatanen, journalist. His health insurance card indicated that Kaarlo Vatanen had been born in 1942.

In the whole book this is the only oddity, the fact that he would have gone running into the forest with his case; it’s not as if he was chained to it by the wrist. But I could live with it.

The photographer gets to town, books into a hotel and then when Vatanen fails to appear heads off back to the spot where he left him to see if he can find him but he can’t; the man and the hare have vanished.

Now if I was to ask you to name another book which begins with a person heading off into the undergrowth in chase of a leporid I’m sure only one would come to mind: Alice in Wonderland. And there is a definite parallel between the two books because both Alice and Vatanen, without a second’s thought, abandon the safety of the real world and head off into a new one filled with eccentric and fascinating characters most of whom are welcoming and accommodating but a few of which are not. In a radio interview the essayist Pico Iyer, who wrote the foreword to the Penguin edition of The Year of the Hare talks about the author:

[H]e was a journalist and in fact the story that he beautifully unfolds in the novel is a reflection of his life. He sold his own boat in order to get some free time to try to write this novel, took a huge risk and lo and behold … the novel became a huge best seller; it’s been in twenty-five different languages. He threw himself into the abyss and the abyss caught him and he now had a wonderful life. – Pico Iyer, Radio without Borders, 15 March 2011

Is there any difference between throwing oneself into an abyss and diving headfirst down a rabbit hole?

In the same interview, the interviewer, Jean Feraca, made this statement about the book: “This is a parable about scarcity and abundance and the lesson we can draw from it is that in scarcity we find abundance.” Hence my opening quotes. Had I been the one interviewed I would have fallen back on my old favourite quote from Huxley’sBrave New World:

Actual happiness always looks pretty squalid in comparison with the overcompensations for misery. And, of course, stability isn't nearly so spectacular as instability. And being contented has none of the glamour of a good fight against misfortune, none of the picturesqueness of a struggle with temptation, or a fatal overthrow by passion or doubt. Happiness is never grand.

Vatanen has not vanished down a rabbit hole or into the hare’s warren. He’s simply headed off into the forest. The next morning we find him awakening in “a sweet-smelling hayloft. The hare was lying in his armpit, apparently following the flitting of the swallows under the barn’s rafters.” The man, however, is going over his life in Helsinki: the egocentric wife he didn’t much care for, the home full of “huge posters and clumsy modular furniture” he didn’t much care for, the job working for a weekly magazine which had sucked out his soul, the spiralling cost of living, the constant debt. Like I said, he could be any one of us.

He heads west. With the hare in his pocket. He doesn’t have especially large pockets; it’s just a very young hare. In time he comes to a village where he buys some cigarettes and a lemonade from a red kiosk. The girl asks him if he’s a criminal because he came out of the forest. He says no and then “Vatanen took the hare out of his pocket and let it bumble around on the bench,” and any issues the girl might have had vanished: “Hey, a bunny!” This sets a pattern that is repeated again and again throughout the book. Any guy who is happy to wander around with a hare like this can’t be a bad guy. The girl directs him to the local vet who bandages the hare’s paw and instructs Vatanen how to care for the creature. The two of them stay there for several pleasant days, the hare getting tamer and tamer all the time.

He heads west. With the hare in his pocket. He doesn’t have especially large pockets; it’s just a very young hare. In time he comes to a village where he buys some cigarettes and a lemonade from a red kiosk. The girl asks him if he’s a criminal because he came out of the forest. He says no and then “Vatanen took the hare out of his pocket and let it bumble around on the bench,” and any issues the girl might have had vanished: “Hey, a bunny!” This sets a pattern that is repeated again and again throughout the book. Any guy who is happy to wander around with a hare like this can’t be a bad guy. The girl directs him to the local vet who bandages the hare’s paw and instructs Vatanen how to care for the creature. The two of them stay there for several pleasant days, the hare getting tamer and tamer all the time.

Vatanen then gets the bus to Heinola, a municipality in the south of Finland where he calls his friend Yrjö:

“Listen, Yrjö. I’m willing to sell you the boat.”

“You don’t mean it! Where are you calling from?”

“I’m in the country, Heinola. I’m not planning to come back to Helsinki for the moment, and I need some cash. Do you still want it?”

“Definitely. How much? Seven grand, was it?”

“Okay, let’s say that. You can get the keys from the office. Bottom left-hand drawer of my desk—two keys on a blue plastic ring. Ask Leena. You know her, she can give them to you. Say I said so. Do you have the money?”

“Yes, I do. Are you including the mooring?”

“Yes, that’s included. Do it this way: go straight to my bank and pay off the rest of my loan.” Vatanen gave him his account number. “Then go to my wife. Give her two and a half thousand. Then send the remaining three thousand two hundred express to the bank in Heinola—same bank. Is that all right?”

Unlike Paasilinna, Vatanen has no plans to write a novel. But his past isn’t willing to let him go so readily: his wife and his boss learn where he is and are waiting for him when he goes to collect the money. He manages to avoid them and skips town leaving only this short note in his hotel room:

Leave me in peace. Vatanen.

For the rest of the book we see a strange transformation take place. The feral hare becomes domesticated and the civilised man becomes wild. Vatanen moves from job to job, mainly manual work: “billhooking and chopping excessive undergrowth from the woods on the sandy ridges around Kuhmo and living in a tent with an ever more faithful, almost full-grown hare,” breaking “up three log rafts on the Ounasjoki River, north of the village of Meltaus” for “the Lapland branch of the TVH, the Water and Forest Authority,” he then takes “a forest-thinning job five miles from the highway that crosses the deserted forest tracts north of Lake Simojärvi,” and while he’s “[s]pending a few days resting at a hotel [in Sodankylä], he [meets] the chairman of the Sompio Reindeer Owners’ Association, who [offers] him a job repairing a bunkhouse in Läähkimä Gorge in the Sompio Nature Reserve.” He then gets “a job repairing a summer villa at Karjalohja, a lakeside hamlet about fifty miles from Helsinki” before returning to Läähkimä Gorge where he gets offered “a job  constructing an enclosure for reindeer” north of the Arctic Circle. All goes well – he’s content, the hare is content – until the appearance of the bear. And then we get to see a different side to Vatanen. Up until this point you might be forgiven for thinking that he was only really interested in running away but suddenly we see him in hot pursuit – and, no, before you think the worst of the poor bear, it’s not gone and killed the hare – but how things are going to end is a mystery. Actually that’s true. How the book ends is a mystery and I’m not going to spoil it by telling you but I didn’t see it coming. The Finnish film copes well with its magicalness; the French one not so much.

constructing an enclosure for reindeer” north of the Arctic Circle. All goes well – he’s content, the hare is content – until the appearance of the bear. And then we get to see a different side to Vatanen. Up until this point you might be forgiven for thinking that he was only really interested in running away but suddenly we see him in hot pursuit – and, no, before you think the worst of the poor bear, it’s not gone and killed the hare – but how things are going to end is a mystery. Actually that’s true. How the book ends is a mystery and I’m not going to spoil it by telling you but I didn’t see it coming. The Finnish film copes well with its magicalness; the French one not so much.

This is a lovely book. It is a book I wish I’d written. It is a book I could have written.

Dromomania, travelling fugue, ambulatory automatism, poriomania– psychologists have come up with a variety of terms based on the fact that some people simply walk out of their lives one day, often, it seems, for no good reason; they go walkabout and often don’t go back. Some take up different identities and occupations and months may pass before they return to their former identities. The most famous case was that of Jean-Albert Dadas, a Bordeaux gas-fitter, who would suddenly set out on foot and wind up in cities as far away as Prague, Vienna or Moscow with no memory whatsoever of his travels. Vatanen is not like this. He never forgets who he is, but once he has tasted freedom he has no desire to go back. I use the term ‘walkabout’ in the casual sense we westerners do but this is no vision quest. One day he’s simply had enough and that’s it.

As of December 31, 2010, the National Crime Information Centre’s Missing Person File contained 85,820 active missing person records. Only a tiny fraction of those are stereotypical abductions or kidnappings by a stranger. It is estimated that 35,000 people are reported missing each year in Australia. This equates to one person every 15 minutes. This is a rate of 1.7 people per 1,000 Australians. It’s hard to find statistics for missing adults: because they’re adults they’re perfectly at liberty to abandon their lives; it’s not a crime. The fact is, though, that, for a whole host of reasons, there are people who decide they don’t want to be a part of the rat race any more. I did. When I walked out of my job back in 2007 I knew in my heart of hearts that I’d never go back to the nine-to-five grind (or in my case the seven-to-four-thirty-plus-a-couple-of-hours-in-the evening-and-most-weekends grind). I didn’t know what I’d end up doing – being a fulltime writer seemed a bit idealistic – but I knew I’d have to start living more for myself and not for others or I was going to kill myself through overwork.

I was lucky and things worked out for me. The whole thing could just have easily gone belly up. And that could have happened to Paasilinna too.

Not everyone can walk out of their jobs, let alone their lives; reading about someone who did is the closest they’re going to get. So if you are looking for a piece of escapist literature, rather than reading about aliens or supernatural creature or equally unbelievable romances, give this wee book a go.

***

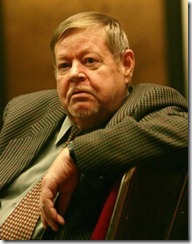

Arto Paasilinna was born in Kittilä in Lapland on April 20th 1942. Paasilinna ("stone fortress" in Finnish) is a name invented by his father, who changed his from Gullstén, following a family conflict.

Arto Paasilinna was born in Kittilä in Lapland on April 20th 1942. Paasilinna ("stone fortress" in Finnish) is a name invented by his father, who changed his from Gullstén, following a family conflict.

From the age of thirteen, he took various jobs, including those of a woodcutter and a farm labourer.

"I was a boy of forests, working the land, timber, fishing, hunting, the whole culture that is found in my books. I was float wood on rivers in the north, a sort of aristocracy of these homeless fixed, I moved from physical labour to a journalist, I went to the forest to the city. Journalist, I wrote thousands of articles seriously, it's a good practice to write more interesting things." [direct quote from his website – not sure if his English is bad or the translation is poor]

He studied general education at the Graduate School of Education People of Lapland and then worked as an intern with the regional newspaper Lapin Kansa. He worked from 1963 to 1988 in various newspapers and literary magazines. He is the author of thirty-five novels but I can only find one other in English apart from The Year of the Hare: The Howling Miller.

Since the publication of Hare Vatanen, the novel that truly launched his career, the writer from Lapland likes to send his characters walking around in Finland, like vagrant existentialists who head off in search of the one thing that is missing from their lives – freedom:

"The Finns are no worse than others, but bad enough that I have something to write until the end of my days."