We use ‘depressed’ as a synonym for ‘sad’, which is fine, as we use ‘starving’ as a synonym for ‘hungry’, though the difference between depression and sadness is the difference between genuine starvation and feeling a bit peckish. – Matt Haig, Reasons to Keep Living

I could’ve written this book. Not everyone could. Of course had I written this book it would’ve been a different book. Not very different. Not better or worse. Just different. My different. Matt and I have quite a few things in common. I think we’d get along if we ever met. We’d do our best to. He seems like the kind of person who’d do his best to and I know I am. It’s always good when you meet someone who gets you and when I picked up this book I thought there’d be lot here I’d be able to relate to. For starters he’s a depressive like me. If we met over a coffee—although maybe not a coffee as it’s one of the things he lists that makes him worse (I can’t say it bothers me)—we could pat each other on the back and say, “At least we survived.” And we both have. Yay us. And we both went on to write books afterwards and probably even because of. The thing is, as I read through Matt’s book I started to realise very quickly that his experiences of depression and my experiences of depression were very different. He’s not a depressive like me. And here’s why:

If you’ve met one person with depression

you’ve met one person with depression.

Stephen Shore said that about autism. You can say the same about every mental illness out there. No two of us are alike. Anyone who says, “I know what you’re going through,” may be sincere in what they say and even believe what they say but NO ONE knows what you’re going through. That doesn’t mean they can’t help. A blind man doesn’t need another blind man to “understand”. He needs a sighted man or a dog to help him avoid potholes and puddles.

This is not a textbook. Matt’s not a psychologist. He’s a bloke who one day woke up no longer in control of himself. He talks about it as if it happened suddenly but it will’ve crept up on him over months, I’m sure. It’s like the smirr we get here in Scotland, that insidious form of drizzle that manages to drench you without you even noticing you’re getting wet and then suddenly you realise you’re sopping wet: when did that happen?

The predominant symptom of both my depressions and, later on, the anxiety was cognitive dysfunction, brain fog as it’s most commonly known. In a word: confusion. For me both depression and anxiety were both forms of confusion. With the depression I could wallow in unsolvable problems; with the anxiety I had a nagging voice inside me demanding immediate solutions to what felt like impossible problems like putting coloured lights on a Christmas tree. The only thing Matt mentioned in passing which sounds similar was “some fuzzy, TV-static, white-noise feelings going on in my frontal lobe” which is not a bad description but it clearly wasn’t the predominate symptom. Matt also never talks about memory loss which was a major, major problem with me during my last breakdown. But that’s fine because Depression is really a blanket term for a whole spectrum of symptoms and just because his illness took a different course to mine doesn’t invalidate either of our experiences. If a man has a broken left leg that doesn’t mean he’s can’t advise a man with a broken right leg how to cope.

Reason to Keep Living is one man’s journey through his depression. It is not a self-help book although there’s a lot in it that’s helpful. It’s primarily a memoir: this is what happened to me, this is how it went away and this is what I learned from the experience. In an interview in The Guardian he was asked, “Is depression different for each person who experiences it?” to which he replied, “I don’t know. I’ve only ever been me.” I concur.

If it is so personal why bother reading it? Because the observations he makes and the conclusions he comes to are common to us all. We all live in the same world. We have just as much chance of becoming depressed as we have of catching the flu although if you’re really unlucky after catching the flu you could wind up with post-viral depression.

And who should read it? Everyone. Although if, like me, you’ve been living with depression for close to forty years (a doctor first prescribed me Librium when I was seventeen) he’s really not going to teach you much. The fact that you’re still alive is indicative of the fact you’ve got a handle on your condition even if it does refuse to go away. As Matt points out:

You can be a depressive and be happy, just as you can be a sober alcoholic.

My sense of humour improves when I’m depressed. Go figure.

I said there were things that I experienced as part of my depression that Matt never mentions. There’s one biggie that he does talk about and one of the major symptoms of most depressions that I didn’t suffer from: suicidal thoughts. Matt writes:

Killer

SUICIDE IS NOW – in places including the UK and US – a leading cause of death, accounting for over one in a hundred fatalities. According to figures from the World Health Organization, it kills more people than stomach cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, colon cancer, breast cancer, and Alzheimer’s. As people who kill themselves are, more often than not, depressives, depression is one of the deadliest diseases on the planet. It kills more people than most other forms of violence – warfare, terrorism, domestic abuse, assault, gun crime – put together.

Even more staggeringly, depression is a disease so bad that people are killing themselves because of it in a way they do not kill themselves with any other illness. Yet people still don’t think depression really is that bad. If they did, they wouldn’t say the things they say.

Things people say to depressives that they don’t say in other life-threatening situations

‘COME ON, I know you’ve got tuberculosis, but it could be worse. At least no one’s died.’

‘Why do you think you got cancer of the stomach?’

‘Yes, I know, colon cancer is hard, but you want to try living with someone who has got it. Sheesh. Nightmare.’

‘Oh, Alzheimer’s you say? Oh, tell me about it, I get that all the time.’

‘Ah, meningitis. Come on, mind over matter.’

‘Yes, yes, your leg is on fire, but talking about it all the time isn’t going to help things, is it?’

‘Okay. Yes. Yes. Maybe your parachute has failed. But chin up.’

That’s two entire chapters by the way. When you’re depressed one thing I can pretty much guarantee you’ll suffer from is poor concentration. And Matt clearly appreciates that despite the fact one of the things that he feels helped him on the way to his recovery was reading until his eyes hurt. That and time. We both agree there. Depression doesn’t like to be hurried along any more than a cold does.

If you’ve never been depressed you can’t possibly know what it’s like. But then I’ve no idea what it’s like to have TB or stomach or colon cancer; I’ve also never set my leg on fire (or any other part of my anatomy) or done anything as foolhardy as jump out of a perfectly good plane. I have had meningitis. And my memory was so poor about eight years back that I couldn’t remember my doctor’s name and had to take a written note with me every time I went because I forgot everything I wanted to tell him so I’ve a pretty good idea what dementia might be like. But I can’t imagine what Matt went through. He does his best to describe it but here’s the problem he has:

It is like explaining life on Earth to an alien. The reference points just aren’t there. You have to resort to metaphors.

Here, then, is how he describes his depression:

Depression, for me, wasn’t a dulling but a sharpening, an intensifying, as though I had been living my life in a shell and now the shell wasn’t there. It was total exposure. A red-raw, naked mind. A skinned personality. A brain in a jar full of the acid that is experience.

And I thought what I went through was bad. Well it was bad. Imagine Hell. Do you imagine Hell would be the same for you as it would be for me? In the book I’m working on just now I describe hell as a place where writers get good ideas all the time but don’t have anywhere to write them down. Anxiety and depression are tailor-made to the individual:

[D]epression is not something you ‘admit to’, it is not something you have to blush about, it is a human experience. A boy-girl-man-woman-young-old-black-white-gay-straight-rich-poor experience. It is not you. It is simply something that happens to you.

And possibly the most important sentence in the book:

Unlike a book or a film depression doesn’t have to be about something.

We, men especially, tend to think in straight lines. Things happen because. The sun rises in the east because. Water turns into steam because. Pimples appear on our face the day of the Prom because. People get depressed because. Well, yes, they do. But here’s the problem:

The more you research the science of depression, the more you realise it is still more characterised by what we don’t know than what we do. It is 90 per cent mystery.

[…]

[S]cientists aren’t all singing from the same hymn sheet. Some don’t even believe there is a hymn sheet. Others have burnt the hymn sheet and written their own songs.

Matt was diagnosed with Generalised Anxiety Disorder. He provides a list of symptoms from the NHS website. You can see it here. That’s what I had the last time (the previous three times it was just your bog-standard depression) or at least my doctor didn’t disagree with my self-diagnosis. He was less interested in labelling my condition—he wasn’t worried about the because—than he was in treating the symptoms. If you haven’t looked at the NHS list take a second to click on the link and scan the symptoms. Here’s what Matt noted:

I believe that the term ‘mental illness’ is misleading, as it implies all the problems that happen, happen above the neck. With depression, and with anxiety in particular, a lot of the problems may be generated by the mind, and aggravate the mind, but have physical effects.

And the list of physical symptoms is longer than the mental ones. I assure you: it’s not all in your head.

Matt adds an additional symptom to his list:

Derealisation. It is a very real symptom that makes you feel, well, not real. You don’t feel fully inside yourself. You feel like you are controlling your body from somewhere else.

I didn’t really feel that. I’d describe what I felt as dislocation. A part of me stepped aside and watched me being irrational and knew I was being irrational and did nothing to stop me. See what Matt says about metaphors. How do you describe an experience like this? Even great writers—and depression is completely  indiscriminate in who it chooses—have been unable to find the words. Churchill talked of a “black dog”, Plath of a “bell jar”. Matt devotes an entire chapter to descriptions of depression but about the only one I suspect we’d all agree on is: “A fucking pain.”

indiscriminate in who it chooses—have been unable to find the words. Churchill talked of a “black dog”, Plath of a “bell jar”. Matt devotes an entire chapter to descriptions of depression but about the only one I suspect we’d all agree on is: “A fucking pain.”

If, like me, you’ve been depressed before and have read tons of books about depression there’s not a lot new here. You will still have to find your own way out of the mire. And the spectre of depression will likely hang over you for the rest of your life. Just because you break your leg when you’re young doesn’t mean you won’t break another bone later in life. Just because you survive cancer doesn’t mean you won’t get another kind later on. And just because you climb out of depression there’s no guarantee that you’ll be able to again. Like Robin Williams:

I was one of millions of people not just saddened by Robin Williams’ death, but scared of it, as if it somehow made it more likely for us to end up the same way.

It’s a thought. It’s even a possibility. But as Matt points out:

[M]ost people with depression – even most famous people with depression – don’t end up committing suicide. Mark Twain suffered depression and died of a heart attack. Tennessee Williams died from accidentally choking on the cap of a bottle of eye drops that he frequently used.

He provides a list of people, famous people, living with depression. There’s a much longer one here:

If you are a man or a woman with mental health problems, you are part of a very large and growing group. Many of the greatest and, well, toughest people of all time have suffered from depression. Politicians, astronauts, poets, painters, philosophers, scientists, mathematicians (a hell of a lot of mathematicians), actors, boxers, peace activists, war leaders, and a billion other people fighting their own battles.

You are no less or more of a man or a woman or a human for having depression than you would be for having cancer or cardiovascular disease or a car accident.

Before I end up copying out the entire book—I’m pretty sure I’ve already passed my “reasonable use” quota of quotes (sorry Canongate)—I’d like to end with the opening of the book’s fourth section, ‘Living’:

THE WORLD IS increasingly designed to depress us. Happiness isn’t very good for the economy. If we were happy with what we had, why would we need more? How do you sell an anti-ageing moisturiser? You make someone worry about ageing. How do you get people to vote for a political party? You make them worry about immigration. How do you get them to buy insurance? By making them worry about everything. How do you get them to have plastic surgery? By highlighting their physical flaws. How do you get them to watch a TV show? By making them worry about missing out. How do you get them to buy a new smartphone? By making them feel like they are being left behind.

Alcoholics do well to stay out of bars. Should depressive stay clear of social networking sites? There is an argument for that especially if you call yourself a writer and you’re not writing; it’s hard being surrounded by dozens of other people all buzzing about their latest book or work in progress. In the chapter ‘Things that make me worse’ Matt includes:

Facebook (sometimes).

Twitter (sometimes).

In the chapter ‘Things that (sometimes) make me better’ he includes:

Facebook (sometimes).

Twitter (sometimes).

So what do YOU do? You do what works for you. After all we’re all trying to be normal. The problem is:

There is no standard normal. Normal is subjective. There are seven billion versions of normal on this planet

On the cover Joanna Lumley (actress and celebrity depressive) says, “A small masterpiece that might even save lives.” You never know and we will never know. How would we ever know? But she is right. No one book can hope to cover everything or cater to everyone and Matt wisely provides an additional reading list at the end of his book. This is not the book on depression to end all books on depression but when others come along I would sincerely hope they list Reasons to Keep Living in their additional reading lists.

I liked this book. It’s a good book. I seriously wish someone had handed me a copy of this book back in 1982 because I had no idea what was happening to me back then. That was my first major depression—I was about the same age as Matt was—and I pretty much went through it on my own. I didn’t even know I was depressed. I’d never known anyone who was depressed. We’re Scots. We get scunnered. No one gets depressed. Wooses get depressed.

I’ll leave you with video of Matt talking about the origins of the book and reading from the opening chapter:

There’s an excerpt on his blog here too. This 2014 article in The Telegraph is also worth a read.

***

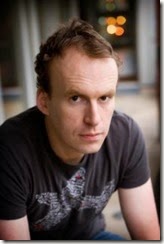

Matt Haig was born in Sheffield, England in1975. He writes books for both adults and children, often blending the worlds of domestic reality and outright fantasy, with a quirky twist. His bestselling novels are translated into 28 languages. The Guardian has described his writing as 'delightfully weird' and the New York Times has called him 'a novelist of great talent' whose writing is 'funny, riveting and heartbreaking'.

Matt Haig was born in Sheffield, England in1975. He writes books for both adults and children, often blending the worlds of domestic reality and outright fantasy, with a quirky twist. His bestselling novels are translated into 28 languages. The Guardian has described his writing as 'delightfully weird' and the New York Times has called him 'a novelist of great talent' whose writing is 'funny, riveting and heartbreaking'.

His novels for adults are The Last Family in England, narrated by a labrador and optioned for film by Brad Pitt; The Dead Father's Club (2006), an update of Hamlet featuring an 11-year-old boy; The Possession of Mr Cave (2008), about a man obsessed with his daughter's safety, The Radleys (2010), a very British vampire novel, and The Humans (2013) which I reviewed here about an alien who comes to earth and discovers his humanity. The film rights to all his adult novels have been sold.

His multi-award winning popular first novel for children, Shadow Forest, was published in 2007 and its sequel, The Runaway Troll, in 2009. His most recent children's novel is To Be A Cat. He lives in York with his wife—and, from all accounts, his salvation—Andrea and their two kids.