Real comes and goes and isn’t very interesting. – Miranda July, The First Bad Man

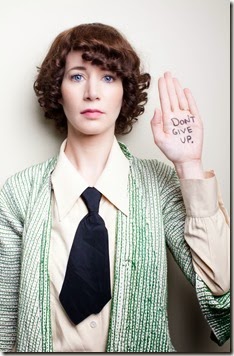

Quirky. It’s an… odd word. When Kate Bush first arrived on the scene she was called “quirky” and it felt like a good fit. Now it’s clearly insufficient. Kate Bush is… well, she’s Kate Bush; there’s no one really quite like her. Except there is. There’s Tori Amos. Or at least there was. She started off as quirky too, moved onto “the new Kate Bush” and has now released enough material that most people recognise her as herself. And the same will happen with Regina Spektor who’s also transcended quirky but maybe not “the next Kate Bush/Tori Amos” tag or at least not yet. When Miranda July arrived people described her as quirky; it clearly covers a multitude of sins. I think what most of us mean when we call something quirky is that it’s different and different makes us uncomfortable; we’re not sure what the rules are. Very few people are truly different, unlike anyone who’s come before them. Or at least not for very long. Glen Miller was just another band leader until he found his sound.

I specifically asked for a review copy of this book. I first encountered July in 2009 when I read her debut short story collection No one belongs here more than you. There was much discussion of the word quirky in the comments to my review. In the review I wrote:

She’s … one of those storytellers who often gets labelled ‘quirky’, a description one needs to approach with caution because it can often mean ‘doesn’t fit anywhere else’. I’ve also heard her called ‘the voice of a generation’, which one I’m not sure. I think X and Y have been used up so I suppose she must be Z and, yes, I’m being facetious.

In 2012 I jumped to read her second book, her debut non-fiction collection It Chooses You, which I managed to review without once using the word quirky. Now it’s the turn of her debut novel. In between I watched her films Me and You and Everyone We Know and The Future. I’ve never seen any of her short films or music videos or multimedia presentations or plays or listened to her music albums. I imagine many of them have been described as quirky. The thing about quirky is that there’s often a slightly disparaging undertone there. And once used it clings. In an interview in The Observer the author (of the article) notes, “July has been called ‘kooky’ and ‘whimsical’ so many times that she’s beginning to tire of it—and it’s hard not to think that these adjectives are designed to be patronising to women.” July’s response?

In 2012 I jumped to read her second book, her debut non-fiction collection It Chooses You, which I managed to review without once using the word quirky. Now it’s the turn of her debut novel. In between I watched her films Me and You and Everyone We Know and The Future. I’ve never seen any of her short films or music videos or multimedia presentations or plays or listened to her music albums. I imagine many of them have been described as quirky. The thing about quirky is that there’s often a slightly disparaging undertone there. And once used it clings. In an interview in The Observer the author (of the article) notes, “July has been called ‘kooky’ and ‘whimsical’ so many times that she’s beginning to tire of it—and it’s hard not to think that these adjectives are designed to be patronising to women.” July’s response?

Yes, it’s pretty clear that ‘whimsical’ is a diminutising word … I almost think asking the question is like I’m being asked to gossip about myself. I think it’s kind of a female thing, being asked to gossip about yourself. I think I’m maybe done with that.

Miranda July is forty-one now and that’s another thing. Expressions like “quirky” and “kooky” do not hang well on a forty-one-year-old woman.

The First Bad Man is not quirky—not in the cute sense—but it is different and in a world where books are currently being churned out at a rate of four every second different is not simply an achievement, it’s a ruddy miracle. I am not sure I’ve ever read another book like it. Except by July. In that respect it’s what I was expecting, nay hoping for. I planned to read it over three days. I actually read it in two. And what did I think? I tend to judge books by two measures: Did the book make me think? Would I benefit from a second read? The answers to these highly personal questions were: Yes and Yes.

What goes on inside people’s heads? I’ve wondered that all my life. What mechanisms, what beliefs, what delusions, what strengths help then get from one day to the next? Are we all that different? Well I’ll tell you what: I’m very different to Cheryl Glickman, the main protagonist in The First Bad Man. But I do get her up to a point. She’s a coper. She arranges her life and her thought processes to help herself cope. For example, she carries a torch for one of her bosses and her fantasies about him help:

I drove to the doctor’s office as if I was starring in a movie Phillip was watching—windows down, hair blowing, just one hand on the wheel. When I stopped at red lights, I kept my eyes mysteriously forward. Who is she? people might have been wondering. Who is that middle-aged woman in the blue Honda? I strolled through the parking garage and into the elevator, pressing 12 with a casual, fun-loving finger. The kind of finger that was up for anything. Once the doors had closed, I checked myself in the mirrored ceiling and practiced how my face would go if Phillip was in the waiting room.

She wears sensible clothes—“I … wear shoes you can actually walk in, Rockports or clean sneakers instead of high-heeled foot jewellery”—and has a unique system for keeping her house in order:

How much time do you spend moving objects to and fro? Before you move something far from where it lives, remember you’re eventually going to have to carry it back to its place—is it really worth it? Can’t you read the book standing right next to the shelf with your finger holding the spot you’ll put it back into? Or better yet: don’t read it. And if you are carrying an object, make sure to pick up anything that might need to go in the same direction. This is called carpooling.

I’m not sure if she’d describe herself as happy—happiness takes a lot of effort—but she’s reasonably content. If it weren’t for the globus (the persistent sensation of having phlegm, a pill or some other sort of obstruction in the throat when there is none) she’d be well on the way there:

I had not flown to Japan by myself to see what it was like there. I had not gone to nightclubs and said Tell me everything about yourself to strangers. I had not even gone to the movies by myself. I had been quiet when there was no reason to be quiet and consistent when consistency didn’t matter

Everyone thinks she’s dull and maybe she is. On the outside. Because you never know what’s going on inside people’s heads. Like Kubelko Bondy:

The Bondys were briefly friends with my parents in the early seventies. Mr. and Mrs. Bondy and their little boy, Kubelko. Later, when I asked my mom about him, she said she was sure that wasn’t his name, but what was his name? Kevin? Marco? She couldn’t remember. The parents drank wine in the living room and I was instructed to play with Kubelko. Show him your toys. He sat silently by my bedroom door holding a wooden spoon, sometimes hitting it against the floor. Wide black eyes, fat pink jowls. He was a young boy, very young. Barely more than a year old. After a while he threw his spoon and began to wail. I watched him crying and waited for someone to come but no one came so I heaved him onto my small lap and rocked his chubby body. He calmed almost immediately. I kept my arms around him and he looked at me and I looked at him and he looked at me and I knew that he loved me more than his mother and father and that in some very real and permanent way he belonged to me. Because I was only nine it wasn’t clear if he belonged to me as a child or as a spouse, but it didn’t matter, I felt myself rising up to the challenge of heartache. I pressed my cheek against his cheek and held him for what I hoped would be eternity. He fell asleep and I drifted in and out of consciousness myself, unmoored from time and scale, his warm body huge then tiny—then abruptly seized from my arms by the woman who thought of herself as his mother. As the adults made their way to the door saying tired too-loud thank-yous, Kubelko Bondy looked at me with panicked eyes.

Do something. They’re taking me away.

I will, don’t worry, I’ll do something.

Of course I wouldn’t just let him sail out into the night, not my own dear boy. Halt! Unhand him!

But my voice was too quiet, it didn’t leave my head. Seconds later he sailed out into the night, my own dear boy. Never to be seen again.

Now she sees him everywhere. “Sometimes he’s a newborn, sometimes he’s already toddling along.” It’s a coping mechanism. “[H]e’s one baby. But he’s played by many babies. Or hosted, maybe that’s a better word for it.” For thirty years they’ve been ships in the night; thirty years of “missed connections”. Of course she doesn’t talk about Kubelko Bondy except to her therapist who, like most therapists, accepts the peculiarities of people without batting an eye: whatever gets you though the night as long as it’s not hurting anyone else… unless they want to be hurt; always that proviso these days.

But then things change. Two things. Firstly, she learns that any chance she might’ve had of being with Phillip has just about evaporated. He confesses to her, “I . . . have fallen in love . . . with a woman who is my equal in every way, who challenges me, who makes me feel, who humbles me. She is sixteen. Her name is Kirsten.” Okay. How do you compete with that? Well, oddly, there is a way and Phillip’s the one who provides it. He wants Cheryl’s blessing. Why Cheryl, after all she’s just a co-worker?

I explained how strong you are, how you’re a feminist and you live alone, and she agreed we should wait until we got your take on it.

[…]

“I said you were . . .”—he looked down at my red knuckles—“someone I had a lot to learn from.” With a firm push he pressed his fingers between my fingers. “And I told her how perfectly balanced you are in terms of your masculine and feminine energies.” We began making a small undulating wave, threading and rethreading our hands. “So you can see things from a man’s point of view, but without being clouded by yang.”

That’s a lot of power he’s just handed her. And she’s not the kind of person to make snap decisions.

The second, and by far more interesting change, is the arrival of Clee. Her bosses ask her to take their twenty-one-year-old daughter in. Cheryl’s known the girl on and off since she was fourteen but only in passing. Always one to oblige Cheryl agrees:

“Clee! Welcome!” She stepped back quickly as if I intended to embrace her. “It’s a shoeless household, so you can put your shoes right there.” I pointed and smiled and waited and pointed again. She looked at the row of my shoes, different brown shapes, and then down at her own shoes, which seemed to be made out of pink gum.

“I don’t think so,” she said in a surprisingly low, husky voice.

We stood there for a moment. I told her to hold on, and went and got a plastic produce bag. She looked at me with an aggressively blank expression while she kicked off her shoes and put them in the bag.

What has she let herself in for? And can she handle it? Something you should know about Cheryl, what she does for a living:

[O]ur real business is in fitness DVDs now. Selling self-defence as exercise was my idea. Our line is competitive with other top workout videos; most buyers say they don’t even think about the combat aspect, they just like the up-tempo music and what it does to their shape. Who wants to watch a woman getting accosted in a park? No one.

And this is relevant because…? Because Clee—a self-described misogynist—is not one to keep her hands to herself. And apart from being half her age Clee’s part Swedish and a big girl: “she had a blond, tan largeness of scale”. You’d think after their first physical exchange Cheryl would simply say things weren’t working out and ask her politely to leave but that’s not how things pan out and the two women develop a very unique way of coping with their differences and the pressures of living together.

And then things get worse.

In an interview for NPR July says:

Without giving too much away, there is an actual, real baby that is made in this book. And one of the most interesting discoveries that I made, as one does when they're writing—like, you don't know everything that's going to happen—was to realize that this book was an origin story, among other things, and that it wasn't one about a baby being made by two people coming together and having sex. It was a baby made by sexual fantasy, by mistakes, by a web created in Cheryl's mind that strung together all these people who eventually overlapped enough to create a baby.

That paragraph feels like a huge spoiler but that’s because I’ve read the book. It’s really nowhere near as helpful as you might imagine but it is fair to tell those sensitive souls out there that there’s a lot of talk—a lot of thinking actually—about sex because—shock! horror!—sex is a coping mechanism and is definitely a part of Cheryl’s life. All I’m saying is: Don’t judge a book by its cover. Cheryl has a vivid imagination although she’s clearly read no porn—or probably any erotica—because her descriptions of sexual relations are painful to read.

But July is right when she says this is an origin story. It’s also a love story. It’s the story of a woman coming to love herself, of a woman moving from coping to living. By the end of this book we’re looking at a very different Cheryl. Another thing—and this was something I picked up from a rather too revealing interview with July for After Ellen—is the problems that come when we prejudge: sometimes a cigar is just a cigar and sometimes a cigar is actually a penis substitute only no one’s told it.

A word about the title: The first bad man is a character in a self-defence DVD. The attackers don’t have names so how would you describe them?

“The one in denim?”

“The first bad man.”

If, like me, you’ve read Miranda July before and enjoyed what you’ve read or been taken in by her films then this will not disappoint. If you know nothing more than you’ve read in this review then it might take you a wee while to find your feet. And you might not like it. There were things  about what happened to the characters I didn’t enjoy reading about or understand (I get frustration; I get anger; I don’t get violence) but she writes well even when she’s writing badly. Cheryl is a three-dimensional character—although not an especially deep one (she doesn’t aspire to much)—and you’ll have rarely seen anyone this naked on the page. That’s the benefit of a first person narrative. The problem with it is that we don’t get the same insight into Clee’s motivations nor any of the others. That said, I’m not sure if I’d got into Clee’s “not-so-bright” head she would’ve had the answers I was looking for; she’s not exactly a deep thinker but that doesn’t mean she’s two-dimensional. Which is okay. It’s okay not to have all the answers. Why do people do the things they do? God alone knows. Half the time most of us have no idea why we do the things we do.

about what happened to the characters I didn’t enjoy reading about or understand (I get frustration; I get anger; I don’t get violence) but she writes well even when she’s writing badly. Cheryl is a three-dimensional character—although not an especially deep one (she doesn’t aspire to much)—and you’ll have rarely seen anyone this naked on the page. That’s the benefit of a first person narrative. The problem with it is that we don’t get the same insight into Clee’s motivations nor any of the others. That said, I’m not sure if I’d got into Clee’s “not-so-bright” head she would’ve had the answers I was looking for; she’s not exactly a deep thinker but that doesn’t mean she’s two-dimensional. Which is okay. It’s okay not to have all the answers. Why do people do the things they do? God alone knows. Half the time most of us have no idea why we do the things we do.

It’s not, however, a masterpiece—the word is overused and hence devalued (there are some people would have you believe Beethoven never put a note wrong)—and there’s room for criticism. One Amazon reviewer (who gave the book a not exactly unreasonable three stars) wrote:

The overwhelming praise for this book is baffling. There are flashes of humour and some great lines, but the book as a whole is dull and bogged down by a lazy narrative voice. The prose is mostly mediocre and unoriginal (yet people are calling it brilliant and unique because she uses a lot of short and sloppy sentences). The characters often feel uninspired and wholly unrelatable, and there's little here to hold the reader's attention. The book is saved by great dialogue that carries us through an otherwise sluggish journey of reflection and confusion. If this is what people think is brilliant, cutting-edge, surreal, or even bizarre, then they aren't reading very many books. I found this very run-of-the-mill and couldn't wait for it to be over. The only thing that kept me reading was the possibility that something truly unique would happen.

There’s clearly a case to be answered here but I suspect what it boils down to it expectation and taste. As another reviewer (who gave the book five stars) put it:

As usual when regarding July's work, either you love it or you deeply hate it, there's no halfway.

I’m not sure I agree with that either. For a more balanced three-star review have a look at what Barry Pierce had to say on Goodreads.

The book made me think. I’d be interested to read it a second time. That’s enough for me. People read too much into stars. Astrologers have been doing it for centuries.

You can read an excerpt from the book here.

I’ll leave you with an interview with the author (she talks about her supposed quirkiness at 24:18):