I felt very still and empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo – Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

Of all the mental illnesses that we’ve labelled the one I expect most people imagine they’ve got a handle on is Depression. I, myself, have suffered from depression-with-a-capital-d since I was a teenager but the more I read about other people’s experiences the more I think the following is true: If you’ve met one person with depression you’ve met one person with depression; I’ve heard the same said of sufferers of autism, Asperger's, Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's. You would think being a depressive I’d’ve approached this book with a degree of empathy—and I did, I did—but almost from the jump I realised I didn’t get the main protagonist. If I didn’t know better I’d say the author hadn’t researched her subject too well but, of course, as this is a thinly-veiled account of Plath’s own life and she committed suicide not long after the book’s not exactly ecstatic reception, I can’t lay that one at her door. All I can say is she wasn’t me and thank God I wasn’t her.

I struggled with this book. I found it dated and that’s fine—it is of its time and were it an historical novel written today I’m sure its author would be lauded for her commitment to accuracy—but society’s moved on; a lot that was accepted as the norm in the early sixties is quite unacceptable nowadays. Attitudes to women for starters although we’re still working on that. As she puts it:

So I began to think maybe it was true that when you were married and had children it was like being brainwashed, and afterward you went about as numb as a slave in a totalitarian state.

This still happens but now we regard it as abnormal behaviour and the societies and organisations that sanction it as backward. It’s easy though to see where the seeds to Esther Greenwood’s breakdown come from though:

If neurotic is wanting two mutually exclusive things at one and the same time, then I'm neurotic as hell. I'll be flying back and forth between one mutually exclusive thing and another for the rest of my days

Society at the time imagined a woman would want nothing more than to be a wife and mother and maybe keep the writing on as a hobby, something to submit to the parish journal. Oddly enough despite being a male I understand exactly the pressure Esther was under; I grew up in a working class household in Scotland where even going to university was still considered an odd thing to do.

Society at the time imagined a woman would want nothing more than to be a wife and mother and maybe keep the writing on as a hobby, something to submit to the parish journal. Oddly enough despite being a male I understand exactly the pressure Esther was under; I grew up in a working class household in Scotland where even going to university was still considered an odd thing to do.

The pressure to conform is a universal one and is a constant theme in modern Young Adult novels. And that’s really what this book is (Emily Gould in her article for Poetry Foundation agrees with me). I’m not using this as a disparaging term however and I’m not sure anyone today would object with Catcher in the Rye being reclassified as a YA novel (which is the book Robert Taubman in The New Statesman compared The Bell Jar to). On one level it’s a classic Bildungsroman. Professor Linda Wagner-Martin, in her essay, The Bell Jar as a Female ‘Bildungsroman’, writes:

Concerned almost entirely with the education and maturation of Esther Greenwood, Plath's novel uses a chronological and necessarily episodic structure to keep Esther at the centre of all action. Other characters are fragmentary, subordinate to Esther and her developing consciousness, and are shown only through their effects on her as central character. No incident is included which does not influence her maturation, and the most important formative incidents occur in the city, New York. As Jerome Buckley describes the bildungsroman in his 1974 Season of Youth, its principal elements are "a growing up and gradual self-discovery,""alienation,""provinciality, the larger society,""the conflict of generations,""ordeal by love" and "the search for a vocation and a working philosophy."

Janet McCann’s book on the subject argues the very opposite, “tracing Esther’s change from apparent knowledge and self-confidence to ignorance and uncertainty as the apparently open horizon shrinks to a point,” which is true up to a point but the point is that Esther survives the experience and (presumably, hopefully) goes on to have the happy and fruitful life of her choosing. Plath, herself, referred to the book as a “potboiler” and an “apprentice work” so I don’t think one should fret too much over descriptions. The real test is: Is it still—allowing her the credit that it was originally—a good read?

The first half, Esther in New York, was, frankly, a bit girly for me but it’s clearly important to see Esther in the company of “normal” women. Had the hero been a male and it’d been a men’s fashion magazine—do such things even exist?—I would’ve also found it equally off-putting. Just not my cup of tea. Once we moved into the book’s second half I found myself more interested; One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest(1975) is one of my favourite books which IMHO wipes the floor with this book. Could twelve years make such a difference? Then again we’ve since had Girl, Interrupted (1993) and Prozac Nation (1994) and, of course, The Bell Jar is going to start to feel tame. Just after I finished reading this book I watched The L-Shaped Room which was released the year before (that would be 1962) and was granted an X certificate by the B.B.F.C.—its tagline was “Sex is not a forbidden word!”—but anyone going to see it looking to be titillated would be sadly disappointed. In both The Bell Jar and The L-Shaped Room things that are discussed openly these days—lesbianism is a side issue in both—are skirted around here but, for its time, I can see why young girls would be drawn to the book if only to read the section where Esther finally does have sex and it’s about as erotic as the single coupling in the dark that we get treated to in The L-Shaped Room.

The first half, Esther in New York, was, frankly, a bit girly for me but it’s clearly important to see Esther in the company of “normal” women. Had the hero been a male and it’d been a men’s fashion magazine—do such things even exist?—I would’ve also found it equally off-putting. Just not my cup of tea. Once we moved into the book’s second half I found myself more interested; One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest(1975) is one of my favourite books which IMHO wipes the floor with this book. Could twelve years make such a difference? Then again we’ve since had Girl, Interrupted (1993) and Prozac Nation (1994) and, of course, The Bell Jar is going to start to feel tame. Just after I finished reading this book I watched The L-Shaped Room which was released the year before (that would be 1962) and was granted an X certificate by the B.B.F.C.—its tagline was “Sex is not a forbidden word!”—but anyone going to see it looking to be titillated would be sadly disappointed. In both The Bell Jar and The L-Shaped Room things that are discussed openly these days—lesbianism is a side issue in both—are skirted around here but, for its time, I can see why young girls would be drawn to the book if only to read the section where Esther finally does have sex and it’s about as erotic as the single coupling in the dark that we get treated to in The L-Shaped Room.

The treatment of mental health has changed radically but, electroshock therapy aside, the second half of the book focuses less on her treatments and more on what she’s doing when not being treated. This is a saving grace because loneliness and confusion haven’t changed since the dawn of time. This is the start of Esther’s initial meeting with Dr Gordon:

I had imagined a kind, ugly, intuitive man looking up and saying “Ah!” in an encouraging way, as if he could see something I couldn’t, and then I would find words to tell him how I was so scared, as if I were being stuffed farther and farther into a black, airless sack with no way out.

Then he would lean back in his chair and match the tips of his fingers together in a little steeple and tell me why I couldn’t sleep and why I couldn’t read and why I couldn’t eat and why everything people did seemed so silly, because they only died in the end.

And then, I thought, he would help me, step by step, to be myself again.

But Doctor Gordon wasn’t like that at all. He was young and good-looking, and I could see right away he was conceited.

Doctor Gordon had a photograph on his desk, in a silver frame, that half faced him and half faced my leather chair. It was a family photograph, and it showed a beautiful dark-haired woman, who could have been Doctor Gordon’s sister, smiling out over the heads of two blond children.

I think one child was a boy and one was a girl, but it may have been that both children were boys or that both were girls, it is hard to tell when children are so small. I think there was also a dog in the picture, toward the bottom—a kind of Airedale or a golden retriever—but it may have only been the pattern in the woman’s skirt.

For some reason the photograph made me furious.

There’s a scene not too dissimilar to this in The L-Shaped Room—Jane’s not got mental problems but she is pregnant and unmarried—and although the doctor there is also a perfectly decent individual you can tell there’s a gulf between the two of them and the main problem is one of gender; neither women conform to what society expects of them. This is how Esther’s interview with Dr Gordon ends:

There’s a scene not too dissimilar to this in The L-Shaped Room—Jane’s not got mental problems but she is pregnant and unmarried—and although the doctor there is also a perfectly decent individual you can tell there’s a gulf between the two of them and the main problem is one of gender; neither women conform to what society expects of them. This is how Esther’s interview with Dr Gordon ends:

When I had finished, Doctor Gordon lifted his head.

“Where did you say you went to college?”

Baffled, I told him. I didn’t see where college fitted in.

“Ah!” Doctor Gordon leaned back in his chair, staring into the air over my shoulder with a reminiscent smile.

I thought he was going to tell me his diagnosis, and that perhaps I had judged him too hastily and too unkindly. But he only said, “I remember your college well. I was up there, during the war. They had a WAC station, didn’t they? Or was it WAVES?”

I said I didn’t know.

“Yes, a WAC station, I remember now. I was doctor for the lot, before I was sent overseas. My, they were a pretty bunch of girls.”

Doctor Gordon laughed.

Then, in one smooth move, he rose to his feet and strolled toward me round the corner of his desk. I wasn’t sure what he meant to do, so I stood up as well.

Doctor Gordon reached for the hand that hung at my right side and shook it.

“See you next week, then.”

I found an article in The Guardian entitled ‘Sylvia Plath: reflections on her legacy’ in which a dozen women talk about Plath’s influence on them. Not one man? I don’t get this. Sylvia Plath is a writer, not a women’s writer. She wrote a book, not a women’s book. Granted men don’t come off too well in The Bell Jar but they’re not all irredeemable bastards; most, like the good doctor above, are simply products of their time doing what they see others doing and assuming that’s what’s expected of them too. But then that’s what the women were doing. And it doesn’t look as if any of them are particularly happy with the world in which they live but although individuals change the world most individuals don’t imagine they could ever change the world and so never try.

The fiftieth anniversary of the book’s publication has just passed and a right kerfuffle’s there’s been over the new cover used by Faber & Faber. There’s a full discussion here but I’d like to highlight one paragraph:

"It should be possible to see The Bell Jar as a deadpan younger cousin of Walker Percy’sThe Moviegoer, or even William Burroughs’sNaked Lunch. But that’s not the way Faber are marketing it. The anniversary edition fits into the depressing trend for treating fiction by women as a genre, which no man could be expected to read and which women will only know is meant for them if they can see a woman on the cover," writes Fatema Ahmed. And I admit, she has a real point here. This 50th Anniversary edition does give the illusion that Plath's work is suited to the airport books section at Tesco, and definitely—we would never see Joyce or T.S. Eliot or Yeats sitting along those shelves. In fact, "books by men" are simply not marketed in this way.

This is a problem. Personally I don’t find the book cover particularly objectionable; it’s just not very apt.

It is true, this book’s lost a lot of its power. If books had been classified back in the sixties then I’ve no doubt whatsoever that this would’ve received the equivalent of an X certificate. The French film Jules and Jim received an X rating in 1962; that was changed to a PG rating in 1991. And that’s how I’d rank The Bell Jar. I’ve no idea if my daughter’s read the book. I know her mother has—she read it in the early eighties—but I do wonder if she passed it on. It’s a book that’s beloved by many and I can see mothers wanting to share the experience with their daughters as something special and the daughters being underwhelmed by it. I reread Catcher in the Rye when I was about thirty-five and was so disappointed by it.

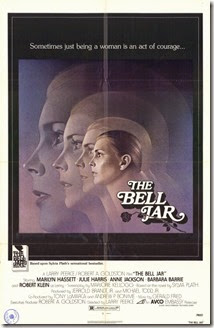

The book has been filmed (in 1979) and some kind person’s uploaded a copy to YouTube. The quality’s not great but it makes interesting viewing. If you’re keen you can see it here until someone makes a fuss about it. The VHS tape was rated R, so the American equivalent of the old X certificate. What can I say about it? Marilyn Hassett—the director’s girlfriend at the time—tries hard but everything’s against her. She apparently read fifteen books on Plath in preparation for the role but the script only pays lip service to the novel. That it would be different to the novel is fine—just compare the film adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest to Kesey’s book (they both work on their own terms)—but the script plods along. You can read Jane Maslin’s less than glowing review of the film (which she wrote for The New York Times) here. In part:

The book has been filmed (in 1979) and some kind person’s uploaded a copy to YouTube. The quality’s not great but it makes interesting viewing. If you’re keen you can see it here until someone makes a fuss about it. The VHS tape was rated R, so the American equivalent of the old X certificate. What can I say about it? Marilyn Hassett—the director’s girlfriend at the time—tries hard but everything’s against her. She apparently read fifteen books on Plath in preparation for the role but the script only pays lip service to the novel. That it would be different to the novel is fine—just compare the film adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest to Kesey’s book (they both work on their own terms)—but the script plods along. You can read Jane Maslin’s less than glowing review of the film (which she wrote for The New York Times) here. In part:

The scenes that are supposed to trigger all the trouble—Esther's confrontations with her mother (Julie Harris) and her strangely sadistic editor (Barbara Barrie), a gratuitously sleazy orgy with a disk jockey (Robert Klein)—are appallingly flat, neither explanatory nor disturbing.

[…]

The script, by Marjorie Kellogg, is full of overwrought extremes, even though Mr. Peerce directs virtually all of it with an inappropriate evenness. The editing of the film is so choppy it calls constant attention to itself. The music, by Gerald Fried, is pretty, and so are the costumes, by Donald Brooks.

To be fair I didn’t really feel the book dealt with the build-up to Esther’s collapse as well as it might have—she seemed pretty together to me during the first part of the book—and this was where the film could’ve done the book a huge favour but it dropped the ball in the first act. I read passages like

The silence depressed me. It wasn’t the silence of silence. It was my own silence.

I knew perfectly well the cars were making a noise, and the people in them and behind the lit windows of the buildings were making a noise, and the river was making a noise, but I couldn’t hear a thing. The city hung in my window, flat as a poster, glittering and blinking, but it might just as well not have been there at all, for the good it did me.

in the book but I really didn’t realise how much she was suffering. In the book, for example, Esther goes to a party and a guy won’t take no for an answer. On getting back to her hotel this happens:

At that vague hour between dark and dawn, the sunroof of the Amazon was deserted.

Quiet as a burglar in my cornflower-sprigged bathrobe, I crept to the edge of the parapet. The parapet reached almost to my shoulders, so I dragged a folding chair from the stack against the wall, opened it, and climbed onto the precarious seat.

A stiff breeze lifted the hair from my head. At my feet, the city doused its lights in sleep, its buildings blackened, as if for a funeral.

It was my last night.

I grasped the bundle I carried and pulled at a pale tail. A strapless elasticized slip which, in the course of wear, had lost its elasticity, slumped into my hand. I waved it, like a flag of truce, once, twice....The breeze caught it, and I let go.

A white flake floated out into the night, and began its slow descent. I wondered on what street or rooftop it would come to rest.

I tugged at the bundle again.

The wind made an effort, but failed, and a batlike shadow sank toward the roof garden of the penthouse opposite.

Piece by piece, I fed my wardrobe to the night wind, and flutteringly, like a loved one’s ashes, the grey scraps were ferried off, to settle here, there, exactly where I would never know, in the dark heart of New York.

Now compare that to the scene in the film:

She hasn’t been raped. But she has had to stand up for herself. A guy tries it on—guys try it on all the time—and although upset, very few women would be traumatized unless they were already on the edge. The writing here’s too poetic, too pretty to do justice to the moment. In this scene at least I can see that the scriptwriter’s heart was in the right place. Her name was Marjorie Kellogg. I doubt anyone will remember her nowadays but I watched another of her films a few months back, a 1970 adaptation of her novel Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon, and it was quite wonderful.

So, bottom line: Would I recommend this book to you? Especially to the blokes out there. I want to say, yes. I do. But there’re only so many hours in the day. I’ve been making a conscious effort to read more books by women this year—which is how I wound up seeking out The Bell Jar in the first place—and what I’m finding is that I’m reading books because I feel I ought to read them rather than reading books that I want to read. The Bell Jar crops up on all sorts of ‘must read’ lists and in 1963 it was a must read but not nowadays. I want to say: No, read One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest instead but there’re three things to consider. Firstly, if you’re reading The Bell Jar because you’re interested in the mentally ill then Kesey’s book is better BUT, secondly, if you’re reading The Bell Jar to gain some perspective into women’s issues then read The Bell Jar, not that you won’t learn a thing or two about women from Kesey but that’s by the by. Thirdly, I’ve not read One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest since I was a teenager so maybe it’s also dated badly. Perhaps I should be recommending something like It’s Kind of a Funny Story by Ned Vizzini—like Plath, Vizzini also committed suicide in his early thirties. Or maybe Will Grayson, Will Grayson by John Green and David Levithan.