Everything disappears his books seem to tell us, and also—in small but omnipresent echoes—everything somehow stays. – Jordan Stump in the introduction to Out of the Dark

In his introduction to Out of the Dark translator Jordan Stump talks about the title he chose to give to this novel:

The French title of this book, Du plus loin de l'oubli, poses a particularly thorny problem, since the English language has no real equivalent for oubli, nor even a simple way of saying du plus loin. The phrase, taken from a French translation of a poem by the German writer Stefan George, is literally equivalent to ‘from the furthest point of forgottenness,’ and I have found no way to express this idea with the eloquent simplicity of the original.

You can read an interview with Stump here.

Out of the Dark is an okay title but that’s as far as it goes. And one might be forgiven for saying that Out of the Dark is an okay novel had its author not just been awarded the Nobel Prize. If I were asked for a single word to describe this book the one I’d go with would be ‘understated’. There’s a lot its narrator never found out and he can’t tell us what he never knew but he’s also looking back on events fifteen and thirty years in his past and so can be forgiven if he doesn’t get every detail straight—in 1964 the couple go to see the film Moonfleetbut as it was released in France in March 1960 it’s unlikely it would still be showing anywhere—but I suspect the real problem with the storytelling is that the narrator doesn’t choose to share everything. What interests him he describes in great detail; the dialogue, for example, moves slowly because he frequently comments on facial expressions and gestures and yet he skips over his past as if it’s entirely inconsequential.

Out of the Dark is an okay title but that’s as far as it goes. And one might be forgiven for saying that Out of the Dark is an okay novel had its author not just been awarded the Nobel Prize. If I were asked for a single word to describe this book the one I’d go with would be ‘understated’. There’s a lot its narrator never found out and he can’t tell us what he never knew but he’s also looking back on events fifteen and thirty years in his past and so can be forgiven if he doesn’t get every detail straight—in 1964 the couple go to see the film Moonfleetbut as it was released in France in March 1960 it’s unlikely it would still be showing anywhere—but I suspect the real problem with the storytelling is that the narrator doesn’t choose to share everything. What interests him he describes in great detail; the dialogue, for example, moves slowly because he frequently comments on facial expressions and gestures and yet he skips over his past as if it’s entirely inconsequential.

A recent article in The New York Times following the news that Modiano had won the Nobel Prize reports:

Peter Englund, the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy, which awards the prize, called Mr. Modiano “a Marcel Proust of our time, “noting that his works resonate with one another thematically and are “always variations of the same thing, about memory, about loss, about identity, about seeking.”

And if that’s the case Out of the Dark is probably as good a novel to read as any if you want a taste of Modiano. Where it is, apparently, a little different is the fact it has little or nothing to say about World War II. According to Wikipedia:

Obsessed with the troubled and shameful period of the Occupation—during which his father had allegedly engaged in some shady dealings—Modiano returns to this theme in all of his novels, book after book building a remarkably homogeneous work.

It’s a short novel—just shy of 150 pages (none of his novels are epics)—and is written in lean, clean, easy to follow prose although he can be a little repetitious at times—just how many times does he need to mention that Gérard Van Bever’s overcoat was a herringbone and Jacqueline’s soft leather jacket was too light for the time of year?—but this is a minor criticism and Dan Brown’s survived worse. The narrator is looking back from 1994—he was born during the summer of 1945 so that makes him about fifty—firstly to the winter of 1964 where the bulk of the novel takes place (over a three or four month period beginning in August), then to 1979 (this time only dealing with two or three days) and finally to the present, October 1994. What ties all three periods in his life together is a woman called (at least in 1964) Jacqueline.

In an interview Modiano makes an interesting observation about his writing (assuming Google Translate’s done a fair job): “If an x-ray of my novels were made, we would see that they contain whole sections of the Profumo affair or the case of Christine Keeler.” Modiano was in London in 1960, the Profumo scandal came to a head in 1963 and his first book was published in 1968. Was Jacqueline modelled on Keeler? Who knows? But read on.

When our unnamed narrator meets Jacqueline she’s a part of a couple but when has that thwarted a full-blooded Frenchman? As I read the opening few pages I was immediately reminded of Jean Cocteau’sLes Enfants Terribles whose title is rarely translated into English these days so I think Stump might’ve been forgiven for digging his heels in and insisting that Du plus loin de l'oubli be kept as the title. The narrator is an outsider (which, of course, suggests another French classic with an untranslatable title) who gets embroiled in a world he’s not entirely comfortable in or fully understands. There is a reference to the novel A High Wind in Jamaica (a book in which children quickly become part of life aboard a pirate ship and treat it as their new home) and there’s definitely a feel of that here but even more so in the London section of the book. The couple he meets are essentially bohemians although neither’s artistic unlike the narrator who aspires to be—and finally does become we discover—a writer. They get by on charity, gambling and finally theft and for some reason open their arms and accept this young man into the fold without any explanation. He’s a dropout. Estranged from his family he lives in a cheap hotel and gets by selling books. He’s a good fit.

When our unnamed narrator meets Jacqueline she’s a part of a couple but when has that thwarted a full-blooded Frenchman? As I read the opening few pages I was immediately reminded of Jean Cocteau’sLes Enfants Terribles whose title is rarely translated into English these days so I think Stump might’ve been forgiven for digging his heels in and insisting that Du plus loin de l'oubli be kept as the title. The narrator is an outsider (which, of course, suggests another French classic with an untranslatable title) who gets embroiled in a world he’s not entirely comfortable in or fully understands. There is a reference to the novel A High Wind in Jamaica (a book in which children quickly become part of life aboard a pirate ship and treat it as their new home) and there’s definitely a feel of that here but even more so in the London section of the book. The couple he meets are essentially bohemians although neither’s artistic unlike the narrator who aspires to be—and finally does become we discover—a writer. They get by on charity, gambling and finally theft and for some reason open their arms and accept this young man into the fold without any explanation. He’s a dropout. Estranged from his family he lives in a cheap hotel and gets by selling books. He’s a good fit.

Modiano largely abandoned his own family and once said of his mother that her heart was so cold that her lapdog leapt from a window to its death. It’s also been said that he does not know where his father’s buried. There’s clearly a lot of Modiano in this book’s main protagonist. In the novel this is virtually all the narrator says about his parents:

I was drifting away from my parents. My father used to meet me in back rooms of cafés, in hotel lobbies, or in train station buffets, as if he were choosing these transitory places to get rid of me and to run away with his secrets. We would sit silently, facing each other. From time to time he would give me a sidelong glance. As for my mother, she spoke to me louder and louder. I could tell by the abrupt way her lips moved, because there was a pane of glass between us, muting her voice. And then the next fifteen years fell apart: a few blurry faces, a few vague memories, ashes . . . . I felt no sadness about this. On the contrary, I was relieved in a way. I would start again from zero.

Jacqueline, for me, was actually the most interesting character in this book. Like the narrator she’s also “underage” but that just means she’s not reached twenty-one and is technically still a minor—why she’s out in the world on her own we never learn—but she copes. She’s manipulative, self-interested and has no problems letting things or people—older men especially—slip though her fingers and fall to the ground once she’s done with them. She abandons Van Bever for the writer (an out of character move considering his age) and then, after a move to London (funded by money stolen from a man called Cartaud who’s been passing himself off as a dentist and also has a thing for Jacqueline) she forsakes the writer without a backwards glance in favour of the slum landlord Peter Rachman.

Rachman, of course, was a real live person although he died in 1962. Wikipedia has this to say:

Rachman did not achieve general notoriety until after his death, when the Profumo Affair of 1963 hit the headlines and it emerged that both Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies had been his mistresses, and that he had owned the mews house in Marylebone where Rice-Davies and Keeler had stayed.

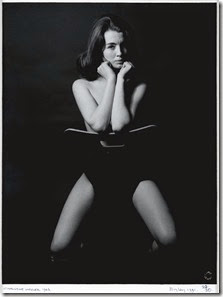

Underlining this connection is the fact that Jacqueline is introduced to Rachman by Linda Jacobsen. In the (in)famous photo by Lewis Morley Keeler sits astride a copy of an Arne Jacobsen chair. Michael Savoundra, who they meet in the Lido with Rachman, is named after Emil Savundra who was an international swindler, confidence trickster and business partner of the real-life Rachman. There are also several references to Jamaicans in this section of the book.

Underlining this connection is the fact that Jacqueline is introduced to Rachman by Linda Jacobsen. In the (in)famous photo by Lewis Morley Keeler sits astride a copy of an Arne Jacobsen chair. Michael Savoundra, who they meet in the Lido with Rachman, is named after Emil Savundra who was an international swindler, confidence trickster and business partner of the real-life Rachman. There are also several references to Jamaicans in this section of the book.

Fifteen years later our writer encounters Jacqueline by chance—they’ve both returned to France by this time—and he follows her gate-crashing a party he suspects she’ll be at. Luckily she does arrive shortly after he does sporting a new hairdo, a new man and a new name but disappears overnight again. A further fifteen years on our writer again sees a woman he suspects might be Jacqueline and follows her for a bit but this time he decides to leave well alone.

None of the characters has what you might call a clearly defined identity and there’s virtually no backstory that we can trust. They’re amorphous beings. Even in his maturity it doesn’t feel like the narrator has settled down; found himself. What could possibly be gained by a third encounter with this woman?

On the little square you come to before the park there was a cafe with the name Le Muscadet Junior. I watched her through the front window. She was standing at the bar, her shopping bag at her feet, and pouring herself a glass of beer. I didn't want to speak to her, or follow her any farther and learn her address. After all these years, I was afraid she wouldn't remember me. And today, the first Sunday of fall, I'm in the métro again, on the same line. The train passes above the trees on the Boulevard Saint-Jacques. Their leaves hang over the tracks. I feel as though I'm floating between heaven and earth, and escaping my current life. Nothing holds me to anything now. In a moment, as I walk out of the Corvisart station, with its glass canopy like the ones in provincial train stations, it will be as if l were slipping through a crack in time, and I will disappear once and for all.

In this book no one is what they seem to be or say they are. Cartaud is clearly not a dentist, Van Bever is not a salesman, the writer’s not a student and he and Jacqueline are neither married nor engaged and yet parts are played as long as it’s convenient. At some later time—after 1979 but before 1994—the writer finds a photograph of himself with Jacqueline and notes, “I was struck by the innocence of our faces. We inspired trust in people. And we had no real qualities, except the one that youth gives to everyone for a very brief time, like a vague promise that will never be kept.” There’s definitely a touch of the mumblecore about this book.

I wasn’t sure about this book at first I have to say. The plain-speaking style is deceptive; it’s subtle. As his translator says in interview:

It is a very simple style, but it’s not plain and it’s not overly poetic. There is a kind of poetry in it, but it’s very discreet. So if you translate him too plainly, or if you translate him too poetically, you completely lose the voice. His voice is very elusive. It’s hard to get a handle on. But it’s straight-forward and it has resonance of meaning that isn’t on.

I recommend you give him a go. I’m not sure looking at the other mooted nominees he would’ve been my choice—we’ll have to wait until 2064 to learn who the competition was—but he’s certainly not a bad writer. He’s an interesting writer, quietly digging his own furrow. Or as he’s put it himself: “I have always felt like I've been writing the same book for the past 45 years.” And that reminds me of Brookner in more ways than one; she also writes short novels that sell remarkably well.

***

Patrick Modiano was born in 1947 in Paris, where he still lives. He received his secondary education at various colleges: Biarritz, Versailles, Chamonix, and Paris. His father, Alberto Modiano, was an Italian Jew with ties to the Gestapo who did not have to wear the yellow star and who was also close to organised crime gangs. His mother was a Flemish actress named Louisa Colpeyn. His family’s complex background set the scene for a lifelong obsession with that dark period in history. His big break came partly due to his friendship with the French writer Raymond Queneau, who first introduced him to the Gallimard publishing house when he was in his early twenties.

Patrick Modiano was born in 1947 in Paris, where he still lives. He received his secondary education at various colleges: Biarritz, Versailles, Chamonix, and Paris. His father, Alberto Modiano, was an Italian Jew with ties to the Gestapo who did not have to wear the yellow star and who was also close to organised crime gangs. His mother was a Flemish actress named Louisa Colpeyn. His family’s complex background set the scene for a lifelong obsession with that dark period in history. His big break came partly due to his friendship with the French writer Raymond Queneau, who first introduced him to the Gallimard publishing house when he was in his early twenties.

His first novel, La Place de l'etoile, published in France in 1967, won the Roger Nimier Prize and Fénéon Prize. Modiano won the Prix Goncourt in 1978 for his novel Rue des boutiques obscures (Missing Person) and the Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française in 1972 for Les Boulevards de ceinture. He also won the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca from the Institut de France for his lifetime achievement in 2010, and the 2012 the Austrian State Prize for European Literature.

Although he has written some twenty-nine novels (which apparently have been translated into more than thirty languages) less than a dozen of his works have made it into English and several of which were even out of print before the announcement of the fact he had been awarded the 2014 Nobel Prize. The award-winning Missing Person had sold just 2,425 copies in the US prior to the Nobel announcement. Yale University had intended to print 2000 copies of his novel Suspended Sentences this year; that’s now been upped to at least 15,000 copies.