I wanted to get the tears out of the way so I could act sensibly. – Joan Didion,The Year of Magical Thinking

I began reading this book the day after my goldfish died. We’d had him for eight or nine years and would’ve happily hung onto him for another eight or nine but he became ill, was refusing food and in the end the kindest thing was to euthanise. At one point I walked back into the living room and my wife asked me, “How’s Fishy doing?” to which I replied, “He’s dying.” At which point I cried. I begin with this not because I think that the loss of a goldfish equates with the loss of a partner but just to show what a softie I am. And yet I never cried reading this book. I didn’t tear up, not once. Towards the end of the book once she starts to pull things together as a form of protracted summary over the last three or four chapters I started to feel a bit for her but her accounts of her husband’s death and the events leading up to his being declared dead (two different things) as well as her accounts of her adopted daughter Quintana’s two extended stays in hospital—twice the girl is at death’s door—were delivered with such dispassion and objectivity that despite the amount of detail, the clinical detail if you will, there were times when I felt like I was reading a textbook rather than a memoir:

This is my attempt to make sense of the period that followed, weeks and then months that cut loose any fixed idea I had ever had about death, about illness, about probability and luck, about good fortune and bad, about marriage and children and memory, about grief, about the ways in which people do and do not deal with the fact that life ends, about the shallowness of sanity, about life itself. I have been a writer my entire life. As a writer, even as a child, long before what I wrote began to be published, I developed a sense that meaning itself was resident in the rhythms of words and sentences and paragraphs, a technique for withholding whatever it was I thought or believed behind an increasingly impenetrable polish. The way I write is who I am, or have become, yet this is a case in which I wish I had instead of words and their rhythms a cutting room, equipped with an Avid, a digital editing system on which I could touch a key and collapse the sequence of time, show you simultaneously all the frames of memory that come to me now, let you pick the takes, the marginally different expressions, the variant readings of the same lines. This is a case in which I need more than words to find the meaning. This is a case in which I need whatever it is I think or believe to be penetrable, if only for myself

One of the reviewers who only gave the book one star—and there were a few (3% on Goodreads which amounts to over 1400 people)—said, “I found only brief spots of actual grief for Didion's husband and daughter, but they weren't enough to overpower my loathing for the author and her self-importance.” I can’t say I loathed the author despite her privileged lifestyle which as far as I can see she worked to attain and there wasn’t enough name-dropping to annoy me in fact I found it oddly sweet that Katharine Ross taught Didion’s daughter to swim. Listening to Liza Minnelli talk about her childhood makes me feel the same. Rich people are allowed to lose loved ones too and grieve in their own way.

I found this comment in an interview in the Huffington Post noteworthy:

Joan said it came to her that everybody she’d known who’d lost a husband, wife, or child looked the same:

“Exposed. Like they ought to be wearing dark glasses, not because they’ve been crying but because they look too open to the world.” It was this rawness that shocked her, she said. “I had spent so much of my life guarding against being raw. I mean, part of growing up for me was getting a finish, an impenetrable polish. And suddenly to be thrown back to this fourteen-year-old helplessness...”

What interests me here is the use of the word “raw” because despite her best efforts I’m sure that rawness didn’t come across. She said it was like “sitting down at the typewriter and bleeding. Some days I’d sit with tears running down my face.” Why did none of that bleed through?

Of course other than fish and a few cats I have lost a couple of humans, both my parents who’d been a part of my life for as long as Didion’s husband had been a part of hers, and I have tried to explore my own grief process—unsuccessfully I should add—but much of the material here didn’t reach me. I suspect this is because the degree to which my parents mattered to me had diminished to such a degree that I barely felt the loss. I was sad but not bereft. I grieved but didn’t mourn. As Didion puts it:

Until now I had been able only to grieve, not mourn. Grief was passive. Grief happened. Mourning, the act of dealing with grief, required attention.

Perhaps if I reread this book once I’ve lost my wife—assuming she passes away before me although she insists that’s not going to be the case—I might feel differently. I found the book interesting which is a word I do tend to overuse but in this instance it’s both the right word and the wrong word: it’s the right word because it accurately describes what I got from the book (I was interested in the outcome) but it’s also the wrong word because others have clearly been deeply affected by what they’ve read. So the difference is between an intellectual appreciation and an emotional connection.

As a memoir all Didion has to measure up to is herself and her own recollections of events. What was interesting was the way things came into focus over time. The nearest I can relate to this is my experience following the breakup of my first marriage. I found myself telling people the story of the marriage trying to work out at which point things went wrong and there were several contenders. Didion does much the same. No one is to blame—she never seeks to blame a person, not even God, although I was never quite clear where she stood there—but she appears to find some comfort from looking back on her husband’s heart problems seeing them in a new light. It’s interesting—that word again—how her husband seemed to find comfort knowing (or at least believing) that he would die from a heart attack.

Much of what Didion goes through is what most people—but most certainly all writers—do: trying to find the right words to make sense out of what’s just happened. Non-writers have to rely on books like this. Didion, too, gains comfort from the writings of others and not only from fiction but technical manuals, too. I’m not like that but my wife is so, although I don’t personally understand the need, knowing someone who is interested in the mechanics of the human body helps me to appreciate Didion’s need. Death is a process which has a beginning and an end; tracing that process—journeying with the person who’s just died—is probably helpful to some. I, personally, felt no need with either of my parents. My father died under very similar conditions to Didion’s husband. He sat in an armchair. One minute he was alive, the next he wasn’t.

Books like this are about the search—pointless though it may be and often is—for meaning. Didion writes:

[We cannot] know ahead of the fact (and here lies the heart of the difference between grief as we imagine it and grief as it is) the unending absence that follows, the void, the very opposite of meaning, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaninglessness itself.

In his review in The New York TimesRobert Pinksy writes:

By attending ferociously to the course of grief and fear, Didion arrives at the difference between "the insistence on meaning" and the reconstruction of it.

He’s not quoting Didion here when he talks of “the insistence of meaning” (it’s from a poem by Frank Bidart—who actually says “Insanity is the insistence on meaning”) but this is exactly what she does. Meaning is a solution to a problem. Julie Andrews wondered how to solve a problem like Maria; Joan Didion wonders how to solve a problem like her husband. Over the months she gathers her facts and assembles her formula only to realise that there are so many things she will never know:

One day when I was talking on the telephone in his office I mindlessly turned the pages of the dictionary that he had always left open on the table by the desk. When I realized what I had done I was stricken: what word had he last looked up, what had he been thinking? By turning the pages had I lost the message? Or had the message been lost before I touched the dictionary? Had I refused to hear the message?

Much of what she does and thinks is irrational and she’s well aware that’s what’s she’s being—she refuses to throw out his shoes in case he needs them when he comes back—and one might wonder how she can be objective and subjective at the same time but from my own experience of depression I can assure you that you can be; it’s a coping mechanism.

There were things I was surprised she skipped over, like the x number of stages of grief—but I was fine with that. After all this is a personal exploration of loss and I think that’s ultimately why I found the book interesting as opposed to moving because I found myself standing with her looking back at what happened as opposed to experiencing things with her; I experienced her reflections on her experiences and not the experiences themselves, a reflection (in all meanings of the word) and not the reality. I think I would’ve preferred a semi-autobiographical novel like P.F. Thomése’s Shadow Child. Novels are often more intimate than any confessional memoir no matter how honest the author tries to be. Autobiography tells you only what the writer recalls and how they want you to think they behaved at the time. Some manage to be more truthful than others. But even the most honest memoir is still a carefully constructed artefact, reality filtered through self-conscious caution. I am not, of course, making any accusations here. Didion is well aware she’s attempting the impossible: “trying … to reconstruct the collision, the collapse of the dead star.”

On March 29, 2007, Didion's adaptation of her book for Broadway, directed by David Hare, opened with Vanessa Redgrave as the sole cast member. The play expands upon the memoir by dealing with Quintana's death which happened a few months after she completed The Year of Magical Thinking and is dealt with in Blue Nights, a memoir about aging. Having just read this article what I now realise is how little we really learn about Quintana in this book. I suddenly see the girl in a completely different light. The memoir may be primarily about Dunne’s death but a large portion isn’t and it would’ve been helpful to learn a bit more about her clearly troubled daughter. Dunne incorporated some of his daughter’s fears into his novel Dutch Shea, Jr. and Didion quotes from the book but not with enough weight. It slips by that Cat is a thinly-veiled Quintana:

On March 29, 2007, Didion's adaptation of her book for Broadway, directed by David Hare, opened with Vanessa Redgrave as the sole cast member. The play expands upon the memoir by dealing with Quintana's death which happened a few months after she completed The Year of Magical Thinking and is dealt with in Blue Nights, a memoir about aging. Having just read this article what I now realise is how little we really learn about Quintana in this book. I suddenly see the girl in a completely different light. The memoir may be primarily about Dunne’s death but a large portion isn’t and it would’ve been helpful to learn a bit more about her clearly troubled daughter. Dunne incorporated some of his daughter’s fears into his novel Dutch Shea, Jr. and Didion quotes from the book but not with enough weight. It slips by that Cat is a thinly-veiled Quintana:

The Broken Man was in that drawer. The Broken Man was what Cat called fear and death and the unknown. I had a bad dream about the Broken Man, she would say. Don’t let the Broken Man catch me. If the Broken Man comes, I’ll hang onto the fence and won’t let him take me…. He wondered if the Broken Man had time to frighten Cat before she died.

The article says, “The secret subject of Joan Didion's work has always been her troubled daughter.” I did not get that.

You can read the opening two chapters of The Year of Magical Thinkinghere.

***

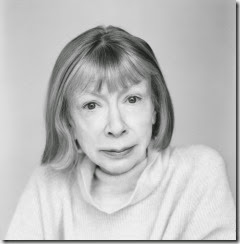

Joan Didion, born in California in 1934 and a graduate from Berkeley in 1956. Her most highly esteemed work is her narrative nonfiction, which she began writing in the 1960's in the form of essays that have over the years appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books, among other publications. Of Didion, Joyce Carol Oates once wrote,

Joan Didion, born in California in 1934 and a graduate from Berkeley in 1956. Her most highly esteemed work is her narrative nonfiction, which she began writing in the 1960's in the form of essays that have over the years appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books, among other publications. Of Didion, Joyce Carol Oates once wrote,

[Joan Didion] is one of the very few writers of our time who approaches her terrible subject with absolute seriousness, with fear and humility and awe. Her powerful irony is often sorrowful rather than clever [...] She has been an articulate witness to the most stubborn and intractable truths of our time, a memorable voice, partly eulogistic, partly despairing; always in control.

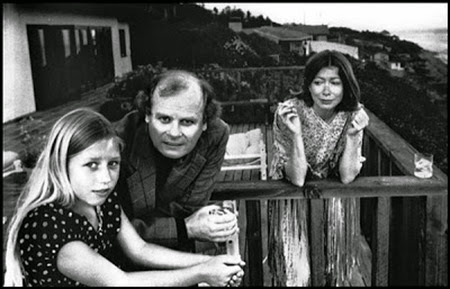

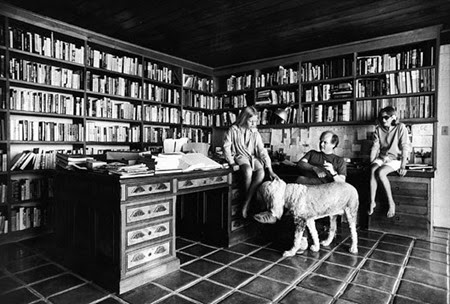

She married John Gregory Dunne in 1964, a fellow writer, and they collaborated on a number of projects, mainly screenplays, probably the most notable being A Star is Born. Unable to have children, in 1966 they adopted a baby at birth and named her Quintana Roo, after the Mexican state.

Didion has published numerous collections of her essays beginning with 1968's classic Slouching Towards Bethlehem, and culminating in Blue Nights which came out in 2012 which I will probably read since I get the feeling it might fill in some of gaps in The Year of Magical Thinking. She is also the author of several novels.