Diseases desperate grown,

By desperate alliances are relieved,

Or not at all.

(Hamlet, IIII.ii.)

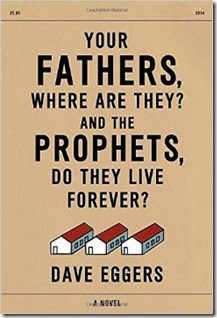

Books written solely in dialogue divide people so I wasn’t surprised to see a lot of one- and two-star reviews for this. I, personally, loved it to pieces. I enjoyed Cormac McCarthy'sThe Sunset Limited and Nicholson Baker’sCheckpoint; Aaron Petrovich’s The Session was good, if a little short, but Padgett Powell’sMe & You was simply wonderful. There are others I’ve still to get round to like Philip Roth’sDeception which I’ll probably have read by the time I get round to posting this.

The all-dialogue technique was pioneered first by Henry Green and later (and more famously) by William Gaddis, who, in 1975, published J R, a book where it is sometimes difficult to determine which character is speaking other than conversational context. I've written two novellas now. Exit Interview was the first and still has the feel of a play very much like The Sunset Limited but In the Beginning was the Word like Your Fathers, Where Are They? And the Prophets, Do They Live Forever? Is pure dialogue. It's so refreshing actually to be able to forget about those boring descriptive passages and what’s going on inside people’s heads. I'm surprised I don't do more of it. I think Your Fathers, Where Are They? And the Prophets, Do They Live Forever?is the best dialogue novel I’ve read yet.

In an interview over at McSweeney’s the author was asked the obvious question and his answer is illuminating:

When I started the book, I hadn’t planned on it being only dialogue. I knew it would be primarily a series of interviews, or interrogations, but I figured there would be some interstitial text of some kind. But then as I went along, I found ways to give direction and background, and even indications of the time of day and weather, without ever leaving the dialogue itself. So it became a kind of challenge and operating constraint that shaped the way I wrote the book. Constraints are often really helpful in keeping a piece of writing taut.

Within the first couple of pages I felt clued-in on where we were and what was happening. It really takes very little. A man called Thomas has somehow kidnapped an astronaut, driven with him to an abandoned military base and handcuffed him to what he decides to call “a holdback for a cannon”. His motive? To ask him a few questions after which he agrees to free him, unharmed. It sounds like a bizarre proposition but it’s not really. John Fowles conceived something similar back in 1963 with The Collector.

The base in question is Fort Ord in California:

Fort Ord is a former United States Army post on Monterey Bay of the Pacific Ocean coast in California, which closed in 1994. Most of the fort's land now makes up the Fort Ord National Monument, managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management as part of the National Landscape Conservation System.

[…]

While much of the old military buildings and infrastructure remain abandoned, many structures have been torn down for anticipated development. – Wikipedia

If only I could talk to him/her. Then they would understand. Or then I’d know. How many people in this world would you like to sit down and have a conversation with? But not just a conversation, an honest exchange. Ten? Twenty? Fifty? But most of the people I’d like to have a chat with wouldn’t give me the time of day. Their security wouldn’t let me within an inch of them even though all I want to do is talk. Kidnapping them is always an option—people get abducted every day of the week—but when I start to consider the practicalities of successfully planning and executing a kidnapping I realise that there aren’t that many people I really want to talk to that much. That said I do have a lot of questions I’d like answers to. Most people in life do. What if those questions started to burn a hole in me? What then? Where would I start?

Thomas starts with a spaceman. He’s called Kev Paciorek. They were at college at the same time. Thomas was three years younger and Kev doesn’t remember him, but apparently they had at least one conversation where Kev revealed he wanted to fly the space shuttle. Thomas never forgot this; he looked up to Kev and followed his career with interest. And Kev does indeed succeed in becoming an astronaut. He does it by hard work and deserves to be admired. And then a year after he gets accepted by NASA the Shuttle is decommissioned. Thomas has done his research:

—You know too much about me.

—Of course I know about you! We all did. You became an astronaut! You actually did it. You didn’t know how much people were paying attention, did you, Kev? That little college we went to, with what, five thousand people, most of them idiots except you and me? And you end up going to MIT, get your master’s in aerospace engineering, and you’re in the Navy, too? I mean, you were my fucking hero, man. Everything you said you were going to do, you did. It was incredible. You were the one fulfilled promise I’ve ever known in this life. You know how rarely a promise is kept? A kept promise is like a white whale, man! But when you became an astronaut you kept a promise, a big fucking promise, and I felt like from there any promise could be kept. That all promises could be kept—should be kept.

—I’m glad you feel that way.

—But then they pulled the Shuttle from you. And I thought, Ah, there it is again. The bait and switch. The inevitable collapse of anything seeming solid. The breaking of every last goddamned promise on Earth. But for a while there you were a god. You promised you’d become an astronaut and you became one.

Now Kev’s waiting on his turn on the International Space Station. And he’s accepted his fate. But Thomas feels cheated on his behalf. Why can the Russians afford their space shuttle when the Americans can’t? Kev tells Thomas:

—They’ve prioritized differently.

—They’ve prioritized correctly.

—What do you want me to say?

—I want you to be pissed.

—I can’t do anything about it. And I’m not about to trash NASA for you, chained up like this.

—I don’t expect you to trash NASA. But look at us, on this vast land worth a billion dollars. You can’t see it, but the views here are incredible. This is thirty thousand acres on the Pacific coast. You sell some of this land and we could pay for a lunar colony.

—You couldn’t buy an outhouse on the moon.

—But you could get a start.

The problem is Kev really doesn’t have all the answers Thomas is looking for. He answers his questions, grudgingly at first, and then with increasing candour but it becomes obvious that he’s only a small cog in the machine. Thomas realises he needs to talk to a bigger cog and excuses himself.

—I have an idea. Hold on a sec. Actually, you’ll have to hold on a while. Maybe seven hours or so. I think I can do this. And here’s some food. It’s all I brought. And some milk. You like milk?

—Where are you going?

—I know you like milk. You drank it in class. You remember? Jesus, you were so pure, like some fucking unicorn.

—Where are you going?

—I have an idea. You gave me an idea.

The action then shifts from Building 52 where he’s holding the astronaut to Building 53 where Thomas has chained up Congressman Dickinson. And he has a few questions for him.

Of course having glanced at the chapter headings at the start of the book I then realised then where this was heading. There were chapters for Buildings 52, 53, 54, 55, 57, 60 and 48. No one can seem to answer the question Thomas really needs to be answered and part of the problem is he’s asking the wrong people the wrong questions but it’s a process and only once he’s gone though it does he—and we—get to see what’s really going on with this guy.

As a flight of fancy goes this is a wonderful premise. I’m not sure than any of us would get the answers we’d expect or want but Thomas does learn some truths. Like what really happened to his friend Don Banh. As the book progresses and Don’s name keeps cropping up we start to realise what the trigger was that set this whole thing in motion. But the really big questions, the meaning of life questions, no, he doesn’t find the answers he’s looking for. And I would’ve been as impressed as hell if Eggers had managed to pull that one off.

Ultimately the issue here is broken promises. Thomas feels that the promises made to him—or at least the promises he believes have been made to him—as a son but especially as an American have been broken. The astronaut was supposed to be his hero but Kev let him down and ultimately everyone’s managed to disappoint him: his parents, his teachers, women, the whole goddam system from the president down to the cops on the beat. Why aren’t the leaders leading the people? Why are thirty thousand acres of prime real-estate lying unused? The politician tries to put things in perspective for Thomas:

—Thomas, nothing you say is unprecedented. There are others like you. Millions of men like you. Some women, too. And I think this is a result of you being prepared for a life that does not exist. You were built for a different world. Like a predator without prey.

—So why not find a place for us?

—What’s that?

—Find a place for us.

—Who should?

—You, the government. You of all people should have known that we needed a plan. You should have sent us all somewhere and given us a task.

—But not to war.

—No, I guess not.

—So what then?

—Maybe build a canal.

—You want to build a canal?

—I don’t know.

—No, I don’t get the impression you do.

—You’ve got to put this energy to use, though. It’s pent up in me and it’s pent up in millions like me.

Thomas isn’t a bad guy. He’s just a guy who can’t live with not understanding why life is as unfair as it tends to be to most people. And he takes matters into his own hands, stupidly, but not more so than the man who walks into the bank that’s repossessed his house and holds them up for the exact amount to settle his debts.  He’s a smart and volatile man, an angry young man, but then young men have been raging against the machine—what Chief Bromden would later call “the Combine”—since the fifties and probably a long time before that thinking about student riots as early as 1918 in Argentina.

He’s a smart and volatile man, an angry young man, but then young men have been raging against the machine—what Chief Bromden would later call “the Combine”—since the fifties and probably a long time before that thinking about student riots as early as 1918 in Argentina.

I completely bought into this and loved its execution. The characters were believable, especially Thomas. If I was to nit-pick—one can always nit-pick—I’d like to know just how Thomas manages to subdue so many people with such ease since most of them are picked up off the cuff without more than a few hours planning and also I was a little disappointed when the cop (who he chooses at random because he “looked more like a dentist”) just happens to be one who was involved in the incident concerning Don Banh. Since Marview is a fictional town, of course, there’s no way to tell how large a police force is has so maybe it’s not that much of a stretch. These really are minor gripes. Some have criticised what they see as sermonising. It’s a fair point. Just watch two or three episodes of Harry’s Law with its current events driven storylines and you’ll realise just how much is wrong with the USA—and not only the States but to be fair this book is a tad Americocentric—and how little good sermons actually do. Actions speak louder than words. Thomas has tried talking—“I’ve written letters to the department and never got an answer. I asked to talk to anyone and no one could bother.”—so now the only thing left is to take matters into his own hands. Desperate times call for desperate measures.

***

Dave Eggers was born in Boston, Massachusetts and grew up in Lake Forest, Illinois, an affluent town near Chicago. When Eggers was 21, both of his parents died of cancer within a year of one another, leaving Eggers to care for his 8-year-old brother, Toph. Eggers put his journalism studies at the University of Illinois on hold and moved to Berkeley, California where he raised Toph, supporting them by working odd jobs. In the early 1990s, he worked with several friends to found Might, a literary magazine based out of San Francisco. The publication gained notoriety when it ran a hoax article describing the death of Adam Rich, a former child actor. Despite the acclaim, the magazine attracted only a limited readership and folded in 1997. In 1998, Eggers founded publishing house McSweeney's, taking on editorial duties of literary journal Timothy McSweeney's Quarterly Concern.

Dave Eggers was born in Boston, Massachusetts and grew up in Lake Forest, Illinois, an affluent town near Chicago. When Eggers was 21, both of his parents died of cancer within a year of one another, leaving Eggers to care for his 8-year-old brother, Toph. Eggers put his journalism studies at the University of Illinois on hold and moved to Berkeley, California where he raised Toph, supporting them by working odd jobs. In the early 1990s, he worked with several friends to found Might, a literary magazine based out of San Francisco. The publication gained notoriety when it ran a hoax article describing the death of Adam Rich, a former child actor. Despite the acclaim, the magazine attracted only a limited readership and folded in 1997. In 1998, Eggers founded publishing house McSweeney's, taking on editorial duties of literary journal Timothy McSweeney's Quarterly Concern.

In 2000, Eggers published A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, a memoir about raising Toph and working for Might. The book garnered a slew of critical plaudits, became a bestseller and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and launched Eggers into literary stardom. For the next five years, Eggers split his time between fiction and charitable projects.

Much of Eggers's later writing has taken a socially conscious bent, building upon his journalism background. In 2006, he published What is the What, the 'fictional autobiography' of Sudanese refugee Valentino Achak Deng. All proceeds from the book were donated to charity, and in 2007, Eggers did the same with the proceeds from Zeitoun, his nonfictional account of a Syrian-American imprisoned in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. In addition to his ongoing literary and charitable work, Eggers co-wrote the screenplays for two films: Spike Jonze'sadaptation of Maurice Sendak'sWhere the Wild Things Are, and, with his wife Vendela Vida, Sam Mendes’sAway We Go.